Go to Part 1

Now that the PCs had been created, I gave them the brief background I had developed to get them launched straight into the one-shot: They had come to the small duchy of Thracia. Recently there had been a gold rush of sorts on artifacts from the ancient Empire of Thracia, and their own researches in the libraries of a distant kingdom led them to believe that they knew the location of the richly accoutered Burial Chambers that had been built during the height of the Empire.

Now that the PCs had been created, I gave them the brief background I had developed to get them launched straight into the one-shot: They had come to the small duchy of Thracia. Recently there had been a gold rush of sorts on artifacts from the ancient Empire of Thracia, and their own researches in the libraries of a distant kingdom led them to believe that they knew the location of the richly accoutered Burial Chambers that had been built during the height of the Empire.

At this point I pulled out the Rumour Table from The Caverns of Thracia. Following the module, I had each of the players roll 1d4 to determine how many rumours their character would know. And then I asked each of them in turn whether they wanted to let the other PCs now what they knew.

All of them said yes, and the randomly generated results gave them various tidbits: One had read a tale of a man who had stumbled out of the jungle raving about “tombs of gold”. The dying words from his bloats lips were, “Beware the yellow death!” Another had encountered a collector in the small logging village on the edge of the jungle — he offered to pay them a hefty bounty on any legitimate Imperial Thracian artifacts. A third had discovered in an ancient tome a reference that said, “In the Empire of the Thracians, even the statues have been given motion and life.”

And so forth. All of these were spontaneous riffs off of the barebones information given from the rumours table.

Then I got to the last PC, Nichol the Dwarf. His player said that she didn’t want to share her information openly. So I took her into the next room and generated her rumours there.

This had an interesting result: Nichol’s kingdom, it turned out, had been plagued by a death cult dedicated to a God of Death known as Thanatos. Efforts to wipe out this cult had failed, but Nichol had discovered that the cult had first arisen in the Thracian Empire. He had come to these jungles hoping to find some secret lore which would allow him to destroy the cult. He had hired the others as mercenaries and treasure-seekers. They remained ignorant of his true purposes.

INTO THE DUNGEON

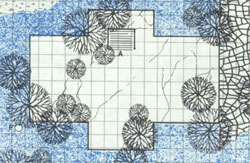

At this point I rolled 1d8 to randomly determine the compass direction from which they would approach the surface ruins above the Caverns. And, in short, order they were pushing their way through the jungle trees in a generally northwesterly direction when they first spotted a large, ruined building coming into view.

The walls of the building were mostly intact, but it was thickly choked with trees and they could see that several trees were actually growing through the roof here and there.

The walls of the building were mostly intact, but it was thickly choked with trees and they could see that several trees were actually growing through the roof here and there.

They began circling the building, trying to find some means of entrance. They didn’t find any, but they did spot a 5′ shaft driven into the earth nearby. They dropped a fiery brand down the hole. About 70′ or so down it landed on finished stone… perhaps there were some columns? It was hard to tell.

They decided not to descend that way, and instead continued circling the building. They found no designed means of egress (which was strange), but they did find a spot on the eastern wall where a tree had literally grown through the wall.

Climbing up, Veera the fighter looked into the ruin. All of the interior wall had long since been destroyed and she could see a wide stairway leading down into the earth. The rest clambered up after her and they headed over to the stairs.

Lighting torches they headed down the stairs. These bottomed out into a long hall covered in bat guano. The bats were still there — hundreds of them clinging to the ceiling. They stirred with angry agitation at the torchlight, prompting the party to douse their torches and switch to a lantern (which could shielded in such a way that the light would not illuminate the upper reaches where the bats were roosting).

Ghaleon the Cleric moved to the front, using his 10-foot pole to tap carefully on the floor. (Anything could be hidden under that thick layer of bat guano.) Coming to the end of the hall they discovered a large alcove with the ruined remnants of a statue. There were also two doors: One spiked shut with an iron piton; the other slightly ajar.

(There was a funny bit of player interaction here based on the description of the way dungeon doors behaved from “Underworld & Wilderness Adventures”:

Doors must be forced open by strength, a roll of 1 or 2 indicating the door opens[…]. Most doors will automatically close, despite the difficulty in opening them. Doors will automatically open for monsters [“What? Like at a grocery store?”], unless they are held shut against them by characters. Doors can be wedged open by means of spikes, but there is a one-third chance (die 5-6) that the spike will slip and the door will shut.

So when they found a door that was slightly ajar, Warrain said, “Careful. I know that doors don’t just stay open by themselves.”

Of course, in retrospect, this is less funny. It was advice they would have done well to heed.)

Ghaleon and Veera began discussing how they should go about opening the door. Veera was inspecting the frame of the door carefully. Ghaleon started probing it gently with his 10-foot pole.

Nichol lost patience with this and pushed the door open. On the floor of the room beyond, he found an injured lizardman stretched out next to the dead bodies of 12 giant centipedes.

Before he had a chance to react, however, the three lizardmen waiting in ambush leapt out. The others could only watch in horror as the lizardmen beat Nichol to the floor with their clubs. Warrain quickly cast a sleep spell, however, and all of the lizardmen fell instantly unconscious.

Ghaleon moved into the room, carefully blessed each of them, and then caved in their skulls with his mace. While he was doing that, the rest of them gathered up the giant centipedes — the lizardmen had aleady eaten the meat from two of them, but the other 10 of them would give them rations for the better part of a week… assuming the meat wasn’t poisonous to non-lizardmen. (It wasn’t. I checked randomly.)

Veera, meanwhile, was poking through the rubble of the ruined statue in the hall. She recovered its original head, revealing the statue to have been of the goddess Athena. Warrain was fairly certain it would fetch a good price from the collector back in the logging village. They bagged it. Then Ghaleon threw Nichol over his shoulder and they retreated into the jungle.

A DIGRESSION ON SURVIVAL

At this point, a brief digression is called for regarding the matter of Nichol’s survival from his brutal beating at the hand of the lizardmen.

In OD&D, there are no negative hit points. If you reach 0 hp, you die. And Nichol hit 0 hp. So why was he still alive?

Well, because of this table:

| Constitution 15 or more: | Add +1 to each hit die |

| Constitution 13 or more: | Will withstand adversity |

| Constitution 9 - 12: | 60% to 90% chance of surviving |

| Constitution 8 or 7: | 40% to 50% chance of survival |

| Constitution 6 or Less: | Minus 1 from each hit die |

Chance of surviving… what?

The rules don’t say. The description of Constitution itself says that, “It will influence such things as the number of hits which can be taken [which it does] and how well the character can withstand being paralyzed, turned to stone, etc.”

But Constitution doesn’t offer any bonus to the saving throws for resisting paralyzation. Should I interpret these rules to mean that effects like paralysis have a chance of killing a character and that the survival percentages for Constitution reflect the odds that they won’t? That doesn’t seem likely to me.

So what I eventually came up with was that I could use these percentages to determine whether or not a character actually survived at 0 hp (while being rendered unconscious and requiring assistance to recover). I’m 100% certain, given my knowledge of how later editions of D&D worked, that this is not what these table entries meant. But if all I had in front of me were these three booklets, that’s what I would have worked out for myself.

And thus Nichol survived… for now.

Continued…

The PCs spent the night in the jungle, eating acrid centipede meat and narrowly avoiding some curious stirges. Shortly before dawn, Cruhst the Cleric heard a large party of some sort moving about in the clearing near the ruins. He crept closer, but it was a moonless night and he couldn’t make out more than vaguely humanoid shadows moving about.

The PCs spent the night in the jungle, eating acrid centipede meat and narrowly avoiding some curious stirges. Shortly before dawn, Cruhst the Cleric heard a large party of some sort moving about in the clearing near the ruins. He crept closer, but it was a moonless night and he couldn’t make out more than vaguely humanoid shadows moving about.