Most of the Mothership adventure reviews I’ve written have focused on the wealth of trifold and other pamphlet modules, but there have also been many zine-style adventures published for the game. Here’s three of them.

THE EARTH ABOVE

James Hanna’s The Earth Above is set on the fast-rotating planet or moon (it’s unclear) of Cor-9. The Helios corporation has lost contact with their mine for unrefined starship fuel and the PCs are sent in to figure out what’s happening and/or get the mine back online. It be as simple as delivering a new communications array!

… but you’ll probably be unsurprised to discover that hostile alien monsters are the real problem.

In this case, the hostile aliens are the Pest. These are clearly heavily inspired by the Alien xenomorphs, but there’s a dash of the psychic bugs from Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers movie in there, too, and some unique twists to their multi-stage life cycle. One of these twists is that the Pest can adapt to a wide variety of food sources, but then become hyper-focused on their chosen source. In this case, they’ve hyper-focused on starship fuel, including the unrefined ore, and infested the mines.

Round that out with a great isometric map of the mines and you’ve got a solid ‘crawl.

But Hanna doesn’t stop there.

Some of the miners survived the initial attack, but are now being held prisoner in the Hab City mining camp by the android miner workers, who have suffered a malfunction due to their core directive to “protect all intelligent life forms.” The directive was meant to apply to humans, but once the androids realized that the Pest were intelligent life forms, they needed to not only protect the humans from the Pest, but the Pest from the humans. And they decided locking everyone up was the best way to do that.

This adds a completely different threat vector to The Earth Above, while also introducing a rich social component to the adventure with a diverse cast of strongly motivated NPCs (human and android alike). And Hanna’s still not done! There’s also a rogue mercenary team loose on the planet who have been dispatched by Xenos Unlimited to secure biological samples of the Pest!

These additional layers add an exponential complexity and depth to the scenario. It’s a good example of how you can take two fairly simple, straightforward adventure ideas, add them together, and get something much greater than the sum of its parts.

The only thing holding The Earth Above back is a patina of strange holes and continuity errors. It’s a difficult to nail this down, but it’s stuff like:

- The mercenary team is both close to the action and 9,000 miles away “on the other side of the planet.”

- The PCs need to deal with threat of the malfunctioning androids… so how many are there, exactly? What security measures have the androids put in place?

- How many survivors are there?

- The adventure assumes the PCs are stranded here without fuel (which ultimately motivates them to journey down into the mine), but it’s unclear why. (The Pest are shown to have drained other ships of their fuel, so perhaps one could imagine adding an attack on the PCs’ ship at some point?)

This stuff is pervasive. Even why the adventure is called The Earth Above is unclear. And the net effect, in actual play, is to throw a bunch of grit in the gears. Unless you take the time to address them in your prep, these countless little snares are going to keep catching you out at the table.

But with a little extra polish, I think The Earth Above can be a really great addition to your Mothership campaign.

GRADE: B-

THE VIEW AT THE END OF TIME

At the end of the universe, an intelligent species evolves, expands, and discovers the cruel trick played it on by fate: They have been born in an era of unimaginable scarcity, as the last stars burn out and the fabric of space-time itself is stretched thin. They look back with envy at the civilizations which were free to plunder galaxies of abundance they hatch a plan: They create a machine capable of ripping a portal through time, but they lack the energy to activate it. What they can do is send a message back in time and hope that some younger race will discover it, decipher it, and open the portal. Then they will be free to journey back and claim what should have been theirs.

Is humanity foolish enough to open a temporal Pandora’s Box?

Of course we are.

And now the PCs have been hired to step through the portal and gaze upon the end of time.

To be honest, you can just inject this one straight into my veins. Everything about The View at the End of Time is aimed straight at my heart, and Elliot Norwood does a very good job of delivering on an incredibly challenging concepts.

As the PCs step through the portal, they find themselves in the preserved ruins of an alien civilization, gazing out on the death of all things in the lurid red glow of a dying sun. Exploring those ruins, they’ll have a chance to begin unraveling the secrets of the Morrow — the name given to these future species by human xenoarchaeologists. As the aliens begin waking up from the long sleep in which they awaited their “saviors,” the PCs will find themselves caught up in the strife

If they’re lucky, they’ll realize in time that their only chance at survival — and perhaps humanity’s only chance — is to flee back through the portal and shut it down from the far side before aliens can use it as a temporal beachhead.

The View at the End of Time is beautiful and horrifying and wondrous all at the same time. I’m very much looking forward to sharing its haunting vision with my players.

GRADE: B

BRACKISH

On the strength of Norgad’s Dead Weight, which I very much enjoyed and have previously reviewed, I immediately grabbed a copy of Brackish, written by Norgad and C. Bell. I recommend you immediately do the same, because I love everything about this adventure.

The basic scenario hook is pretty typical for a Mothership adventure: A corporation has lost contact with a research outpost. They’ve hired the PCs to figure out what happened.

Where Brackish shines, however, is in concept, execution, and detail.

First, they provide a player map of the facility. This seems like a small thing, but it’s literally the first thing at least ninety percent of my Mothership tables ask for when they’re sent on a mission like this: Obviously the corporation would have a map of their facility. Obviously that would be useful. Can we have it please? Brackish anticipating this need and providing what I need is just one example of how Norgad and Bell are intensely focused on the experience of actually running and playing this adventure at the table.

For the GM, the map is supported by an excellent key. The rooms are detailed and evocative, and their descriptions well-organized and easy to use. The layout cleverly uses box outs to provide rich detail while keeping the core presentation free of clutter, and the whole thing is supported by a cleverly compressed version of the map on every spread so that you always know exactly where you are. (So clever that it was only on the second reading that I realized what it was. So bear a wary eye, but once you spot it, it’s invaluable.)

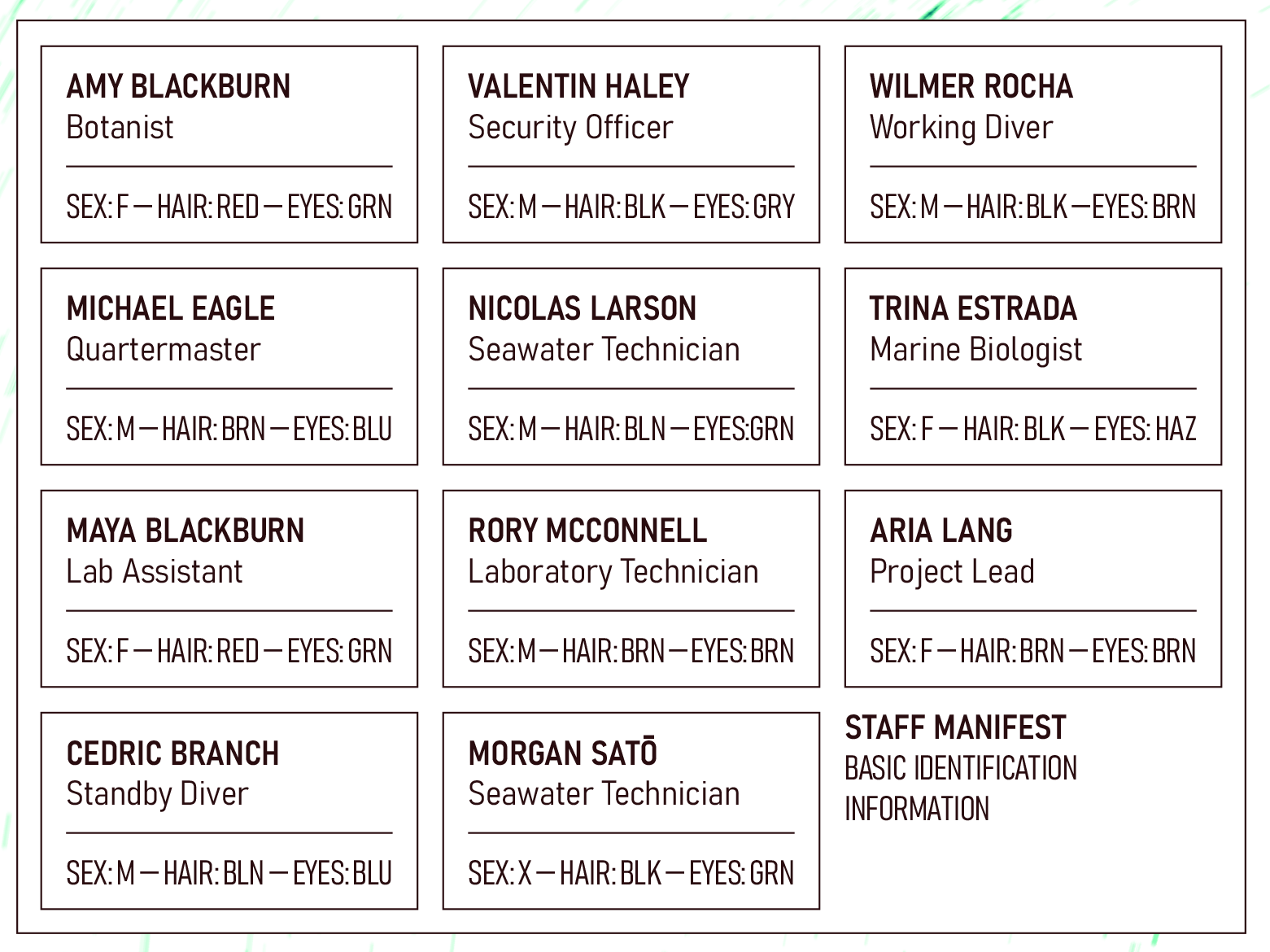

Second, they elevate the generic trope: The corporation doesn’t just want a generic “investigation.” They want the PCs to account for the whereabouts of all station personnel, and the adventure immediately gives the PCs a staff manifest including names, jobs, and descriptions:

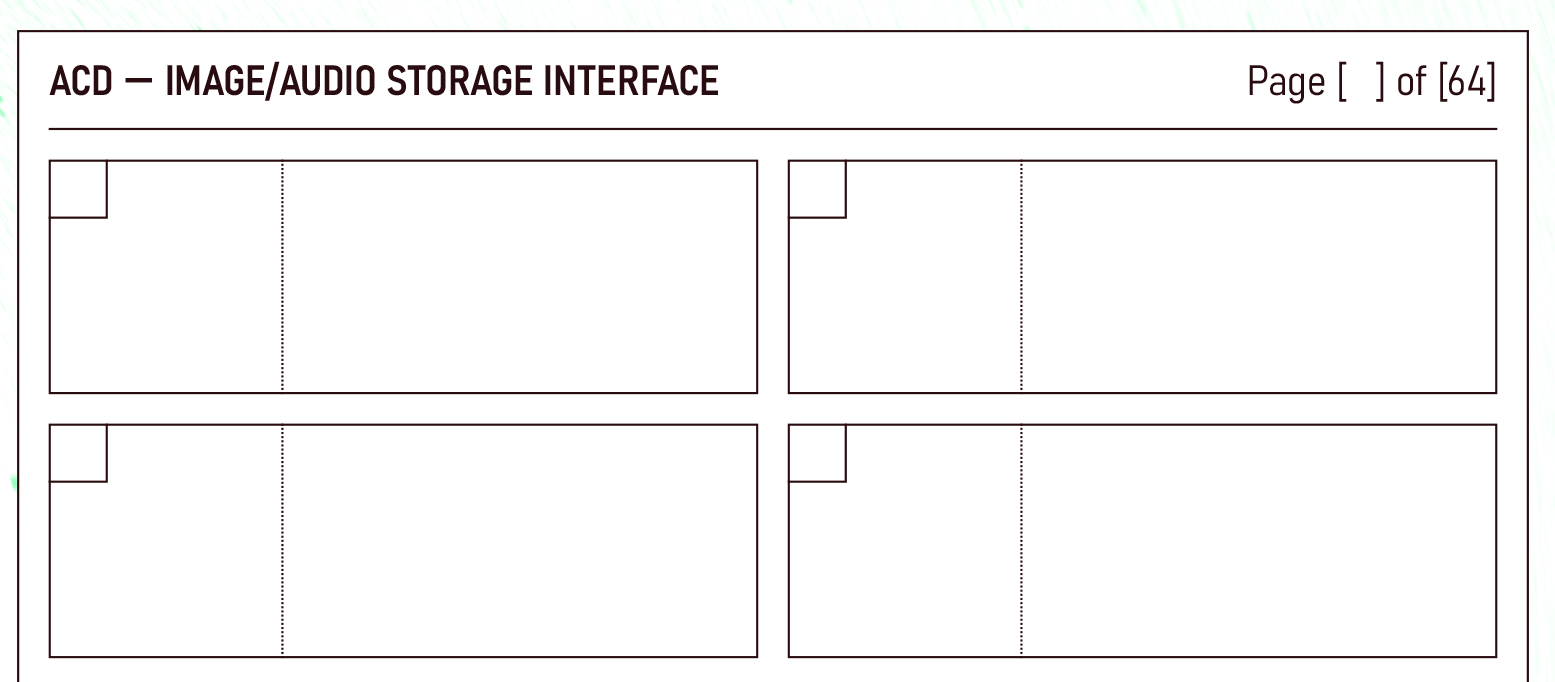

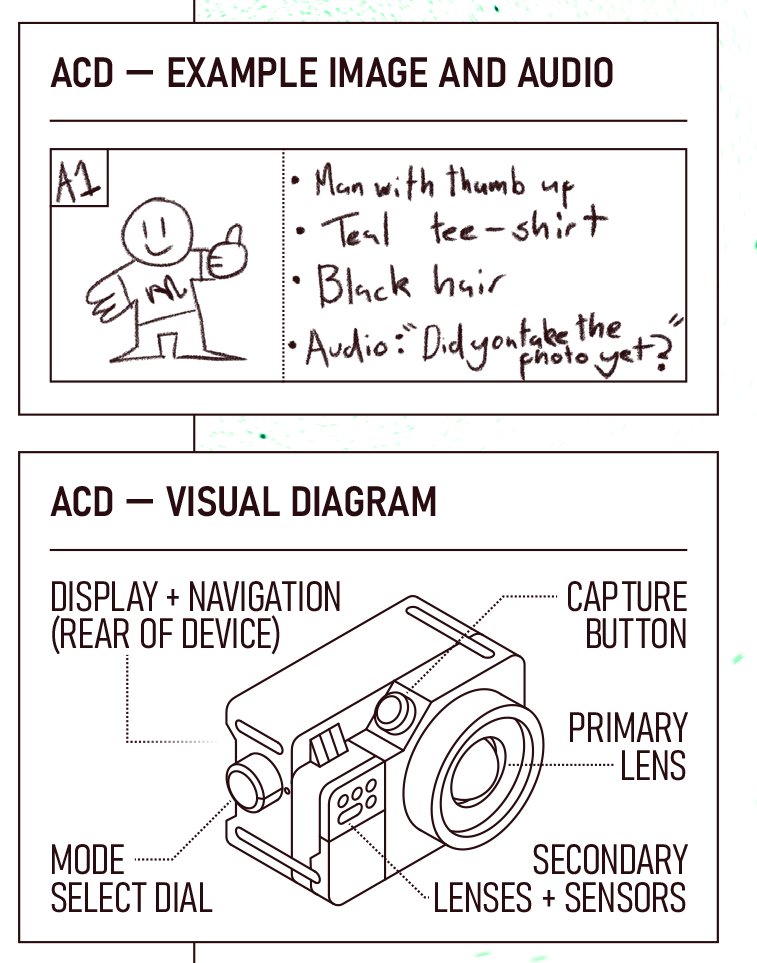

But the corporation doesn’t just want a verbal report: They want evidence. So they provide the PCs with a cryptographic camera that they can use to record secure visual and audio evidence, and to track this the players are given a worksheet:

The concept is that the PCs will track the recordings they make, keep brief notes on what the recordings contain, and draw a sketch of what they’ve filmed.

I’ve never seen this concept before, but it brilliantly pushes the players to creatively engage with the game world in a novel way while simultaneously using notetaking to force an attention to detail, sucking them into the scenario and immersing them into the environment.

engage with the game world in a novel way while simultaneously using notetaking to force an attention to detail, sucking them into the scenario and immersing them into the environment.

They wrap up this whole aspect of the adventure with a detailed breakdown for the GM of every NPC — their current whereabouts (dead or alive), what happened to them, and the specific evidence the PCs can use to discover (and document) their fate. In other words, a comprehensive revelation list. I’ve seen so many published adventures screw this up, effectively forcing the GM to solve the mystery for themselves before they can run it for the players, but Brackish again gives you exactly what you need.

But there’s still more!

Third, Brackish makes the environment dramatically dynamic: A malfunctioning pump is causing roughly half the facility to flood, then drain, and then flood again in a forty-minute cycle. The idea is to track this in real time, using the environment to put pressure on the players and create a sense of urgency.

This element would be a little smoother if the key provided some clear insight into flooded vs. non-flooded rom conditions, but even without that, it gets the job done.

Finally, we have the monster of the week. “A bloated corpse, skin taut and silver-smooth like a pregnant mirror.” A strange, alien artifact transforms those around it into guardians with two key features: It can pass into, through, and out of reflective surfaces. And its touch gives flesh the texture of wet clay, allowing the creature to wipe away the features of its victims. The result — gliding unnaturally and relentlessly through the murky waters — is a truly terrifying nemesis that will haunt your players’ nightmares.

After one round in the tentacles’ grip, the features of the face are left crooked. After two, spun like a whirlpool. After three rounds, the face is polished away completely. The eyeballs are still in there somewhere, sunken beneath the surface.

Then, on top of all this, Brackish rounds things out by providing a custom soundtrack (that you can also use as a countdown clock for the flooding) and a bevy of print-and-play handouts for our players.

Very few published adventures reflect what my complex adventure prep actually looks like. Brackish does. Not because I’ve done something exactly like it — I haven’t! — but because Bell and Norgad have layered multiple scenario and scene structures together to create the desired situation and effect. It’s a technique that not only lets you prep and run complex scenarios with confidence, but delivers truly unique experiences — experiences like Brackish! — for the players.

GRADE: A