This is, in many ways, a house rule document, although it is primarily concerned with setting material rather than mechanical content. I’m a big fan of Bruce R. Cordell’s The Strange. I find its premise fascinating and the possibilities of the setting refreshingly vast. It’s a truly delightful twist on the interdimensional genre.

But having spent a few years playing around with The Strange, there are a few tweaks to the metaphysics of the setting which I think enrich it for the purposes of gaming, and I think other prospective GMs of The Strange might find them useful to consider.

REWIND THE TIMELINE

I’ve talked about the potential benefits of rolling back the clock on a published RPG setting previously.

For The Strange specifically, the thing I note is that the Estate — as described in the core rulebook and sourcebooks — is aware of and has relationships with a lot of different organizations and threats. The Estate has fully established itself among the major players, carved out a specific role for itself, and is also very knowledgeable of the current state of affairs as far as the Strange is concerned.

If you’re running a campaign in which the PCs are (or are likely to become) Estate agents, I’m going to recommend that you roll the timeline back to a point before that’s all true. Let the players experience the “first contact” experiences of the Estate and help determine exactly what place the Estate carves out for itself (and how that will affect the fate of the entire planet and the many recursions which it sustains).

One option would be for the PCs to be among the very first agents recruited by Katherine J. Manners after her experiences with Carter Strange (as described in Bruce R. Cordell’s Myth of the Maker novel). This would make for a campaign roughly equivalent to the first days of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the summer of 1942; much as the agents of the OSS were confronted with figuring out how an intelligence agency should work from scratch, the PCs would need to invent what it means to be a Strange agency from scratch.

The approach I would advocate as a more general structure for The Strange would place the action four or five years after that (the equivalent of joining the CIA during its early days): The Estate is an established organization, the campus in Seattle has been built, and they have at least several dozen active agents. At the moment they:

- Are well-established in Ardeyn and Ruk.

- Have explored or “made contact” with over a hundred other recursions and have active missions in at least a dozen of them.

- Using the Morrison Fellowships (and other, more nefarious means) to detect, monitor, and shut down individual projects which threaten to ping the Strange.

- Tracking and shutting down incursions from the Strange.

- Tracking and recruiting quickened individuals.

They have just recently:

- Discovered that independent “recursion miners” exist. They are now tracking the activities of several, and this department is ramping up.

- Made contact with the Quiet Cabal (see below), who has also made them aware of the existence of the Karum. These are the first major Strange-related organizations that the Estate has become aware of an begun interacting with.

The Estate is NOT aware of:

- Circle of Liberty; they may discover the Circle’s activities as a result of investigating Dr Gavin Bixby (The Strange, p. 154), and then later uncover its connections to the Karum as a result of liaisoning with the Quiet Cabal

- September Project

- Office of Strategic Recursion; the CIA discovered quickened individuals as a result of the MJ-12 projects and the OSR has been around for decades

- Spiral Dust; which may not even have started being distributed yet (I imagine the PCs being the first ones to make contact with it)

- Butterfly Objectors; these disaffected former recursors are only just beginning to organize (and Dedrian Andrews is still an Estate Agent, see The Strange, p. 155).

Basically, the vibe you’re looking for is that the Estate feels very large and well-established and the big fish in the Strange pond when the campaign starts… but they’re about to discover that there are more big players out there than they ever suspected.

Taking a little peek into the future, I will also now suggest that what will set the Estate apart from the other extant organizations is their willingness to form alliances and working relationships with the inhabitants of the recursions they interact with. Where most of the other “big players” take an Earth First (or Ruk First) approach and look on the Strange as a resource to be exploited or a danger to be guarded against, the Estate has a more holistic approach to the problems of Earth and its shoals.

STRANGE SCIENCE

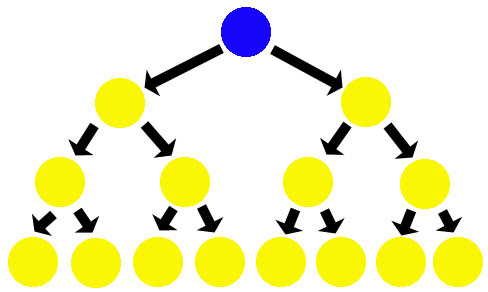

One of the major priorities of the Estate’s research department has been to explore how “Strange Science” works. Their initial efforts at a Unified Theory of the Strange was that different recursions operate under distinct “laws”: Mad Science, Magic, Psionics, and so forth. The reality, however, has proven more complex than this.

Standard Physics — the rules of physics as they exist in the prime reality of Earth’s universe — is also fundamental to all recursions.

In any circumstance where recursions appear to allow effects impossible under the laws of physics, that is almost always because the Strange is actively creating and sustaining that effect. When you cast a spell in Ardeyn, for example, the fundamental reality is not that the laws of physics on Ardeyn allow spells to work; it’s that the dark energy network of the Strange recognizes the spell as being consistent with its model of the Ardeyn recursion and it actively creates that effect. The distinction is subtle, but important.

Substandard Physics: In a recursion with substandard physics, the Strange network appears to do exactly the opposite. Instead of enabling acts which are not compatible with physics, it actively prevents or suppresses actions which physics would normally allow. A common example are fantasy recursions where gunpowder won’t ignite.

Exotic Physics: The exception which proves the rule are exotic recursions. In these recursions, the Strange has fundamentally altered the laws of physics. These effects are generally fairly minor (like varying the gravitational constant), but radical departures are also possible. These recursions are incredibly dangerous to visit through inapposite gates, as the proper functioning of the human body is rather dependent upon the laws of physics. (Visiting them through translation is just fine, since the translation process creates a body consistent with the local exotic laws. Although, in this case, leaving the exotic recursion can be equally dangerous.)

TRANSFERRING REALITIES

When traveling via translation, the Strange takes care of realigning people, creatures, and objects to their “new reality”. Where things become complicated is when inapposite gates allow matter to transfer directly from one recursion to another (or to Earth) without going through the translation process.

Transferring Technology: The first thing to note is that mixing-and-matching reality is not something which can be easily generalized. The Menzoberranzan, Harry Potter, Ardeyn, and Middle Earth recursions all feature magic wands, but the wands which work in one recursion may not be “compatible” with another. The same thing applies to, say, laser guns from different science fiction recursions. On the other hand, sometimes they do.

Technology taken through an inapposite gate to an incompatible reality will become “buggy”, becoming subject to a depletion roll once per use or once per day. On a failure, the technology stops working. The severity of the depletion roll usually defaults to 1d20, but the GM can set a different threshold if they feel it appropriate.

Note that technology with an Earth origin will work in virtually all recursions, the exceptions being those with substandard or exotic physics.

Stabilized Technology: Some technology, however, will become stable within the new reality. This can happen as a result of a GM intrusion, but can also occur if the technology succeeds at a number of depletion checks equal to the die type. (For example if a 1 in 1d20 depletion roll succeeds 20 times without breaking down, the tech becomes stable.)

Some stabilized technology actually becomes an artifact, but most stabilized technology will become unstable again if it’s taken through another inapposite gate.

Working with Impossible Technology: Although existing items can be brought through an inapposite gate, attempting to create new versions of those items (or repair them) outside of the incursions where their creation is part of the simulation never works. (You can import Star Trek phasers, but you can’t create them on Earth.)

The underlying cause of this behavior appears to be that items are “tagged” by the Strange network as possessing certain attributes. Inapposite gates move those items to a new context (possibly bypassing the normal translation-based safeguards of the Strange), but they’re still tagged with a particular functionality and the Strange will continue to actively enact that functionality.

Revelatory Technology: Sometimes, however, the Strange is allowing technology to work because it follows the normal laws of physics in ways that humanity doesn’t understand yet. This technology is incredibly valuable, because you can bring it back to Earth, figure out what makes it tick, and replicate it.

Some believe that this technology actually offers a glimpse into the unimaginable civilization which originally created the Strange. But it’s also possible that the Strange is simply working from templates created by other civilizations. Or perhaps the Strange itself is some sort of insane (or simply incomprehensible) artificial intellect. We just don’t know enough to be sure.

Cyphers and Artifacts: Cyphers and artifacts fundamentally seem to work due to the same principles that allow other forms of technology to work in alien recursions. The distinction is that cyphers and artifacts can also pass through the normal translation-based firewalls of the Strange. (Carter Strange once described these items as having “sysop privileges”.)

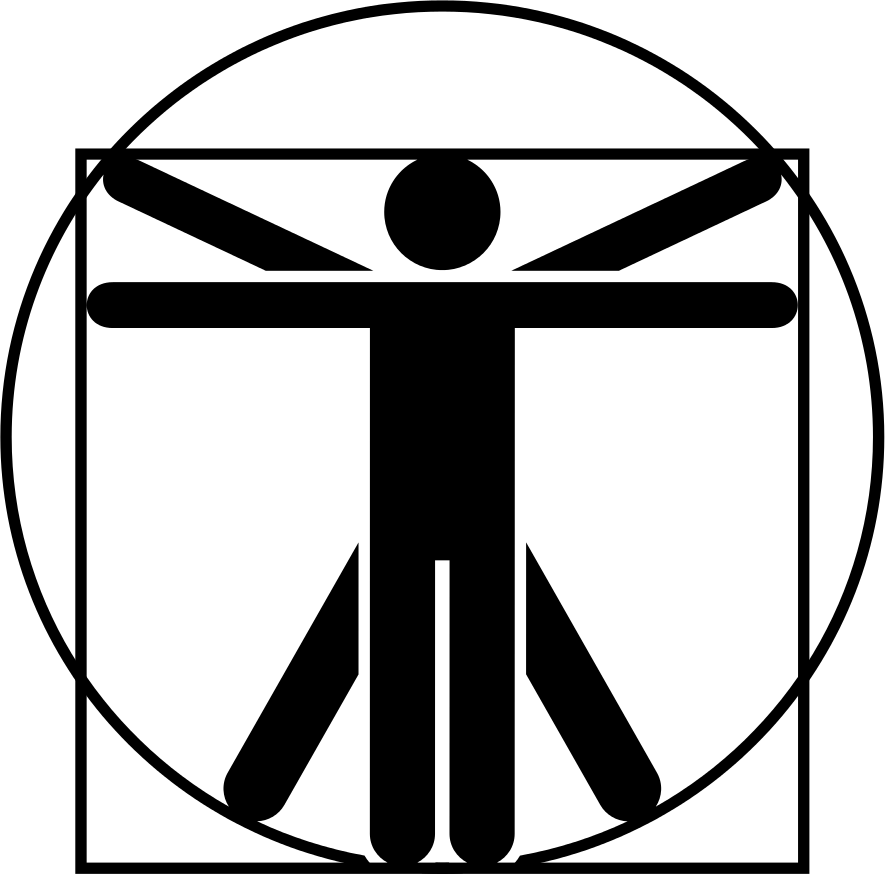

Transferring Life: Unlike technology, lifeforms passing through inapposite gates usually have no difficulty, although environments which would naturally be lethal to them will, of course, continue to be so (including exotic recursions, as described above). The best hypothesis for the distinction is that the byzantine, alien operating system underlying the Strange somehow gives priority to life.

If that’s the case, the Strange network’s definition of “life” seems to be fairly broad, encompassing virtually any independently operating entity (including things like animate skeletons and robots).

If that’s the case, the Strange network’s definition of “life” seems to be fairly broad, encompassing virtually any independently operating entity (including things like animate skeletons and robots).

Fortunately, it appears that the Strange contains some sort of limited hazmat protocol that weeds out viruses and most microscopic / sub-atomic entities. “Gray goo” nanotech can’t propagate through inapposite gates; nor can the civilization-ending flu from The Stand.

(No firewall is perfect, of course, as the zombie outbreak in Oklahoma in 2014 amply demonstrated.)

It should also be noted that taking sentient creatures without the Spark through an inapposite gate will often awake the Spark within them.

In a manner similar to that found with technology, creatures with physiologies sufficiently incompatible with their current recursion (or the prime reality) are also unable to breed or otherwise reproduce: You can bring a Tribble to Earth, but they won’t take over the entire planet. (Taking a Tribble to a Star Wars-derived recursion, however, will probably result in varied forms of hilarity.)

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.