Tagline: Two words: Bizarre. No wait, that’s only one word. Uhhh… Okay: Really bizarre. How’s that? Good? Good. Great. Okay.

CONCEPT

Government-Funded Robot Assassins from Hell – Mission One: Kill All Evil Game Designers (henceforth, for obvious reasons, referred to merely as Government-Funded Robot Assassins) is a card game dating back to 1995.

Government-Funded Robot Assassins from Hell – Mission One: Kill All Evil Game Designers (henceforth, for obvious reasons, referred to merely as Government-Funded Robot Assassins) is a card game dating back to 1995.

Basically it combines a tongue-in-cheek presentation of “government-funded robot assassins from hell” with a satiric look at the gaming industry. Hence you get cards like:

Steve Jackson. He has his own game company! Creator of gaming chaos, this man is wanted by not only the Pentagon, but also the Secret Service! KILL HIM NOW!

And:

Favorable Review. Everyone loves it! It could be because the game is good or maybe the designer slipped the reviewer some cold, hard cash.

(Note: Any game designers wishing to slip me cold hard cash should contact me via e-mail to obtain my snail mail address. I have no scruples. None at all. Honest.)

THE RULES

You win the game by earning a hundred points. Points are earned by carrying out a successful assassination – your targets being various game designers (each of whom are worth varying amounts).

Basically each player starts with a Plain Bot (a really basic model of robot assassin) and a hand of seven cards. You roll 4d6 to determine who plays first (why 4d6? I don’t know). Each player then draws a card and places a target on the table. Then he plays a card (which modifies the score of either his robot or a target, depending on the type of card). Everyone does the same thing.

When play returns to the first player he may now place a second card and then he needs to attack his target (the card he played back on his first turn). To carry out the assassination attempt he adds up his Assassinate score (his ‘bot plus its modifiers) and adds 4d6. If the total is higher than the defense of his target, then the target is dead and the player collects the points. Play out a new target.

Repeat until someone wins.

SUMMARY

I ended up picking up Government-Funded Robot Assassins because I was ordering a number of products from Propaganda Publishing and my eye caught the title (which is very catchy, you have to admit). Since it was only six bucks I added it to my figurative cart. I’m very disappointed by it.

Basically I would sum the game up by its major problems:

First, the production values are very low. Hand-scribbled lettering in the graphics, which are generally low quality anyway. The game as a whole shows up as a set of cardstock pages (the cards, which you have to cut up yourself) folded into a large sheet of xeroxed instructions. This isn’t too bad, overall, since the whole product is basically one large in-joke – so you’re hardly going to expect laminated perfection — but it’s still a knock.

Second, the game – by it’s very nature – ends up being very topical. And the topic is now half a decade old. To put that in perspective, realize that Magic: The Gathering was new, TSR was still independent, and SHADIS still existed. It’s not a knock against the game as it was originally conceived, but it is a knock against purchasing it today.

Third, the rules are presented in a rather sloppy manner in a couple of places. A far larger problem with the rules, however, is that they just aren’t that effective or fun. Your average assassination almost always succeeds, particularly once you start building your robot up (you can move your assassinate score up, but not down – while you are able to modify defensive scores in both directions).

Finally, the jokes were never that funny to begin with. I picked a couple of the more humorous ones, above, but most of them are just yawners. For example:

Wizards of the Coast. The publishers of a hot new card game. Though they have money, they aren’t exactly in the same league as TSR. If they survive Magic, look out!

(Okay, that’s a little funny now — in an ironic sort of way.)

At the end of the day, this just isn’t worth your time or your money. It has a note of pleasant nostalgia to it for “old timers”, like myself, who happened to be kicking around when the events discussed on these cards were unfolding. But that’s not reason enough to pick it up.

Style: 2

Substance: 2

Author: Philip J. Reed, Jr.

Company/Publisher: Propaganda Publishing

Cost: $6.00

Page Count: n/a

ISBN: n/a

Originally Posted: 2000/03/12

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

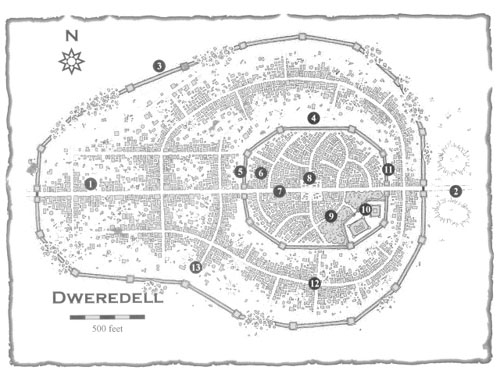

In a specific investigation, on the other hand, the PCs are poking around with a particular goal in mind. This is where the urbancrawl layers become significant: They’re not just looking for anything of interest, they’re specifically looking for a patron. So instead of randomly selecting content from your available layers, you’ll key the specific content tied to the patron level of your urbancrawl.

In a specific investigation, on the other hand, the PCs are poking around with a particular goal in mind. This is where the urbancrawl layers become significant: They’re not just looking for anything of interest, they’re specifically looking for a patron. So instead of randomly selecting content from your available layers, you’ll key the specific content tied to the patron level of your urbancrawl. The most obvious mechanic here would be a Gather Information check. You could set a universal DC for the check (DC 15 to perform an urbancrawl investigation); or you could vary it by city (DC 15 in the City-State of the Invincible Overlord, but DC 20 in the more tight-lipped City-State of the World Emperor); or you could vary it by urbancrawl layer (DC 10 for the Random Encounter layer, DC 20 for the Vampire layer); or you could define it for each key entry (DC 15 to find the blood den in Midtown, but DC 22 to find the den in the Nobles’ Quarter).

The most obvious mechanic here would be a Gather Information check. You could set a universal DC for the check (DC 15 to perform an urbancrawl investigation); or you could vary it by city (DC 15 in the City-State of the Invincible Overlord, but DC 20 in the more tight-lipped City-State of the World Emperor); or you could vary it by urbancrawl layer (DC 10 for the Random Encounter layer, DC 20 for the Vampire layer); or you could define it for each key entry (DC 15 to find the blood den in Midtown, but DC 22 to find the den in the Nobles’ Quarter).