Big social events are a great set piece for an RPG campaign: They’re hotbeds of intrigue. If violence needs to break out, the innocent bystanders raise the stakes. If there’s to be a murder, they provide a wealth of suspects. If the PCs are trying to pull a heist, they delightfully complicate the proceedings.

I’ve also found them to be effective as a way of signaling when the PCs have changed their sphere of influence. You rescued the mayor’s daughter from a dragon? Chances are you’re going to be the belle of the ball. And you’re going to discover that powerful and important people have become very interested in making your acquaintance.

When these events work, they’re exciting and engaging experiences, often providing a memorable epoch for the players and spinning out contacts and consequences that will drive the next phase of the campaign. The difficulty, of course, is getting them to work properly: They require the GM to juggle a lot of different characters and getting the players to actually form a meaningful relationship with the NPCs at the party can often feel like a crapshoot.

Fifteen years ago, however, largely through trial and error, I sort of “cracked the code” on how to prep and run these types of scenarios. Over the years, I’ve used the same scenario structure repeatedly in a wide variety of circumstances – political caucus, soiree on a flying ship, dinner in a mystic castle, journey on a long-haul space freighter – and it’s proven to be remarkably reliable in producing great gaming experiences featuring intensive roleplaying opportunities.

The structure can be broken down into four tools: The location, the guest list, the main event sequence, and the topics of conversation.

LOCATION

Where is the social event taking place?

You’ve got a lot of flexibility with this. I’ve run these types of events in everything from a simple ballroom to multiple flying ships ( with the event moving back and forth between the vessels).

with the event moving back and forth between the vessels).

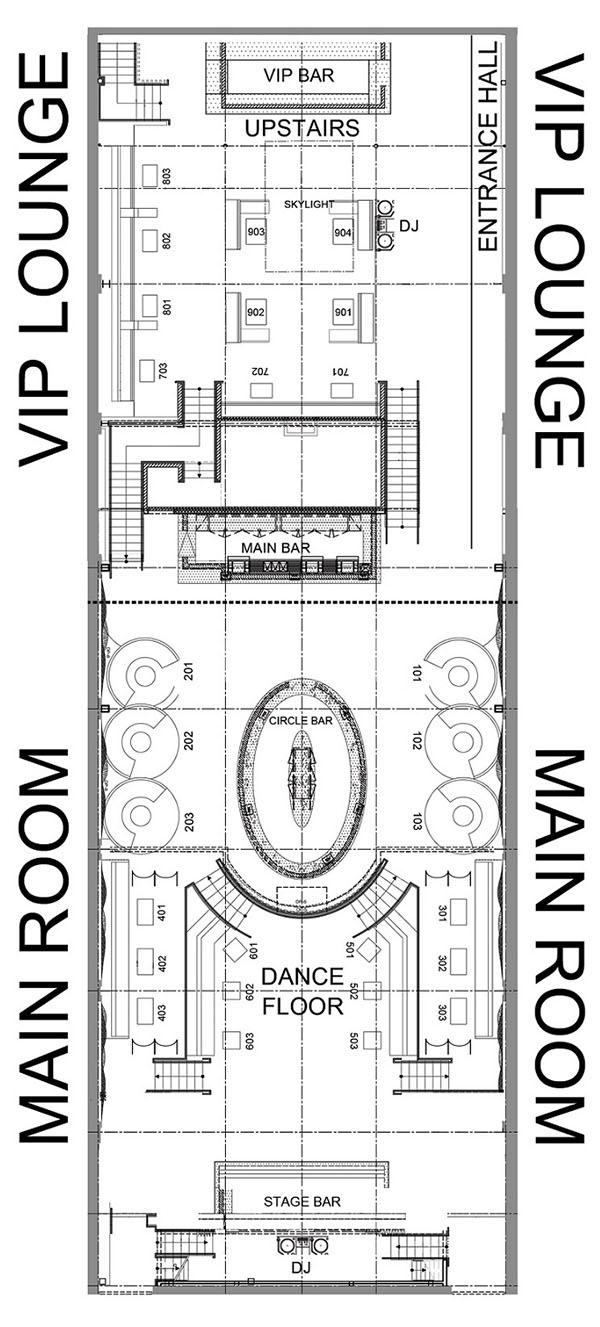

What you want to avoid, however, is making the location too small or too simple. The key to any good party is having multiple zones of activity, so that social groups can form and break apart freely. Similarly, as we’ll see, what makes this scenario structure tick is that the PCs are NOT simultaneously engaged with every single NPC at the event. (That’s a different kind of event – a board meeting or a union rally or something of that ilk.) In order for that to work, there needs to be a lot of different areas that the group can move between.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that you need lots and lots of different rooms. For example, in a nightclub the dance floor, the bar, and the VIP area are probably all in view of each other, but they’re distinct areas that people can congregate in.

On the other hand, it doesn’t hurt to incorporate a wholistic environment, either. The Enchantment Under the Sea dance in Back to the Future, for example, uses the dance floor, the punch bowl, the backstage area, and even the parking lot outside. Including private areas (or at least theoretically private areas) can also be a good idea, not just for the opportunities they provide for the PCs to seclude themselves, but because seeing NPCs slipping into or out of such privates areas can immediately invoke intrigue.

GUEST LIST

Next, you’ll want to prep the guest list. In my experience, you’re generally going to want 10-20 people. Fewer than ten and the event isn’t dynamic enough and doesn’t really feel “large”. More then twenty and the lack of focus kind of just devolves into noise. Fifteen or so feels like a pretty good sweet spot to aim for.

(Obviously many events will have a larger attendance than that. But you’ll want to focus on the circle of NPCs that are immediately relevant to the PCs.)

First, you’ll want to prep a master list of names that you can use as a quick reference while running the event.

Next, you’ll want to prep each of these important NPCs using the Universal NPC Roleplaying Template. The template will let you quickly pick up each NPC and slip into their role during the event.

Next, you’ll want to prep each of these important NPCs using the Universal NPC Roleplaying Template. The template will let you quickly pick up each NPC and slip into their role during the event.

I recommend printing out one NPC per sheet and keep them loose-leaf. That will let you quickly pull out the sheets for each NPC participating in a particular conversation for easy use. If you’ve got the time and resources, it can also be rewarding to prep a visual handout for each NPC. During each conversation, you can just quickly prop up the visual handouts for each NPC present, making it easier for the players to track who they’re talking to and enhancing their memory of each character as a separate individual. (They can also serve as handy visual reminders for you.)

KEY INFO: The Key Info section of the roleplaying template is designed for scenario-essential information that is crucial for the GM to remember when using the NPC. When using the template for a social event, this can include:

- The character’s relationship with or attitude towards other NPCs. (“Despises Susannah.” or “Will enjoy swapping war stories with the naval officers.”)

- Specific reactions that they might have to stimuli. (“Is angered by anyone suggesting that her father is dying.”)

- Particular actions or interactions that should be triggered. (“Will try to poison Cassandra’s drink.” or “Wants to sell the PCs timeshares in Venice Beach.”)

- Clues that can be gleaned from them. (“Knows the knife belonged to Cassandra.” or “Perception check (DC 20) to notice that her dress has been torn.”)

- Scenario hooks.

- Cross-references or common experiences that they share with particular PCs. (“Was raised in the same orphanage as Bella.” or “Was a friend to the duke they killed in session 3.”)

- Unusual or important gear they might be carrying. (“Her glass eye allows her to see through walls.” or “The golden cross she wears is made of aurum (true gold).”)

Obviously some of these categories overlap with each other, and there are plenty of other essential details that will be scenario- or character-specific.

MAIN EVENT SEQUENCE

Next you’re going to prep what I call the main event sequence for the event. For example:

- Announcing Guests of Special Honor

- Iron Mage Appears

- Aoska Arrives

- Urlenius Arrives

- Lord Dallimothan Arrives

- Lady Rill Joins the Party

- Arguing About the Balacazars

- Debate of the Twelve Commanders

- Sheva and Jevicca Seek Out the PCs

- A Poetry Reading

I usually prep these as a linear sequence (A happens, then B happens, then C happens). You could also just prep a grab bag of events that could happen in any sequence. (You could even stock a random table and roll to see what happens next.) If you want to run something a little more complicated, you could also try prepping multiple event sequences. (This is a variant of the Second Track.)

Obviously the PCs can also initiate alternative “major events”, or they may end up derailing (or transforming) the events that you’d originally planned. More power to them. The main event sequence should be seen as a tool, not as destiny.

It can also be tempting to think of the main event sequence as the “Story of the Party”. But it isn’t. It’s more like the piece of string that you dip into a saturated sugar solution in order to make rock candy. The experience of the party – the cool and unique events that you and your players are going to remember – will crystallize around the string. If you’re eating the string instead of the candy, you’re doing it wrong.

TOPICS OF CONVERSATION

The last tool you’ll prep are topics of conversation. These might be momentous recent events, fraught political debates, or just utter trifles (like the series finale of a television program). For example, in a scenario I ran as part of In the Shadow of the Spire, the topics of conversation included:

- A recent riot

- A magical battle that the PCs had been involved in

- A string of terrorist attacks that had been plaguing the city

- Rumours of war to the south

- The health of a guest who canceled at the last minute

- A magical STD that had been afflicting merchant families

- The recent prison escape by a criminal the PCs had arrested

- A new restaurant that recently opened in the Nobles’ Quarter

I recommend mixing in a few “irrelevant” topics of conversation to camouflage (or, at least, contrast) the “important” stuff.

The topics of conversation can also pick up elements from the main event sequence as they happen. (“Did you see Astoria rush out in tears? What could Rupert have possibly said to her?!”)

In some cases, you may want to reference topics of conversation in the Key Info section of the NPCs from your guest list (i.e., what they think about or can contribute to a particular topic). But for the most part you should be able to simply improvise what various people have to say about each topic. What can be more useful is figuring out two or three different general viewpoints on a particular topic (supporting the new Ironworkers’ Guild vs. thinking it’s a front for criminal activity), and then you can just have each NPC ad lib within that debate.

RUNNING THE PARTY

First, you’ll want to know what happens in the first moment that the PCs show up for the event. What will immediately attract their attention? Who will they see? Is there a major announcement (about them or otherwise)? Is there something big and loud going down? Is there something subtle that only they might notice?

This will generally be the first event on your main event sequence. It’s the initial hook and it should give your players enough context to begin taking action in the scene. (Reacting to what they see. Going to speak with someone they know. Et cetera.)

From that point forward, running the event is largely a matter of picking up the various toys you’ve constructed and then putting them into play in different configurations.

- Which NPCs are talking to each other? (Consult your guest list.)

- Who might come over and join a conversation that the PCs are having? (Again, guest list.)

- What are they talking about? (Look at your topics of conversation.)

Encourage the PCs to split up. Cutting back and forth between various conversations is extremely effective in large social events, and you’ll want to use crossovers between various interactions to make the party feel like a unified whole. (For example, if one of the PCs gets involved in a huge shouting match with the Ariadnan diplomat, the other PCs should either hear it directly or hear people talking about it.)

Keep the social groups circulating. You don’t have to completely use up everything interesting about a particular NPC in a single interaction. In fact, you shouldn’t. Reincorporate characters that the PCs met earlier in the scene. Similarly, reincorporate topics of conversation – let the players discuss similar things with different people in order to get (and argue) different points of view.

Pay attention to which NPCs “click” with the PCs (whether in a positive or negative way). In my experience, there’s really no way to predict this: Part of it is just random chance. Part of it is which character traits particularly appeal to your players. Part of it will be which NPCs are clicking for you (and therefore providing stronger and more memorable interactions). Regardless, make a point of bringing those NPCs back and developing the PCs’ relationships with them.

If things feel like they’re lagging, either cut to another group of PCs or trigger the next event on the main sequence.

Don’t hog the driver’s seat. Allow the PCs to observe things that they can choose to react to. (For example, instead of having every NPC come to them, instead allow them to notice NPCs walking past or overhearing a group talking about a topic of interest. Let them choose whether and how to engage.) Make a point of asking them what they want to do (and if they don’t have an answer, trigger the next event).

What essentially makes this scenario structure work is that you have not prepped a dozen specific interactions for the PCs to have. Instead, you’ve prepped a couple dozen different toys – people, topics, events – and you’re going to constantly remix those into new configurations for as long as they hold the players’ interest.

QUICK ‘N DIRTY VERSION

The full scenario structure I’m describing here obviously requires preparation to run to full effect. But what if the players have just spontaneously decided to crash the society debut of the Governor’s daughter? Is there any way to use this scenario structure on-the-fly?

Here’s the five minute version for emergency use:

- Make a list of 3-5 places people can congregate.

- Make a list of 10 characters.

- Make a list of 5 events.

- Make a list of 5 topics of conversation.

Don’t go into detail. Just list ‘em.

If this social event is growing organically out of game play, then you’ve probably already got the NPCs and the topics of conversation prepped – you just need to pull them onto the lists for this event.

Finally, if the PCs are going to the social event in order to achieve some specific goal, use the Three Clue Rule and figure out three ways that they can do that. Notate it in the appropriate places. (For example, if they’re trying to figure out who in the Governor’s circle of friends might have assassinated Marco’s sister, then you’ll probably want to identify a couple people who can tell them that. And maybe one of the events is an opportunity to witness the Governor’s chief of staff slipping off to talk to a known Mafioso.) Of course, when you’re actually running the scenario don’t forget the principle of Permissive Clue-Finding – there may be a bunch of other ways for the PCs to also accomplish their goal. Follow their lead.

For a detailed example of this scenario structure in practice, check out Running the Campaign: A Party at Shipwright’s House.

For example, imagine that the PCs are police detectives and they walk into a room that has a corpse lying in the middle of it. The intentions in this scene will most likely take the form of questions they want answered. But how specific do the questions need to be before the GM can make a ruling on whether not they can find an answer?

For example, imagine that the PCs are police detectives and they walk into a room that has a corpse lying in the middle of it. The intentions in this scene will most likely take the form of questions they want answered. But how specific do the questions need to be before the GM can make a ruling on whether not they can find an answer?