From Volume 1: Men & Magic, pg. 5:

Number of Players: At least one referee and from four to fifty players can be handled in any single campaign, but the referee to player ratio should be about 1:20 or thereabouts.

From Volume 2: Monsters & Treasure, pg. 3:

| Monster Type | Number Appearing* |

|---|---|

| Men | 30 - 300 |

| Goblins/Kobolds | 40 - 400 |

| Orcs /Hobgoblins/Gnolls | 30-300 |

* Referee’s option: Increase or decrease according to party concerned (used primarily only for out-door encounters).

And from Volume 3: Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, pg. 16:

And from Volume 3: Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, pg. 16:

Large Party Movement: Parties numbering over 100, including pack or draft animals, will incur a 1 hex penalty. Parties over 1,000 incur a 2 hex penalty.

These passages, colletively, refer to a style of gaming quite distinct from the modern standard in which a “campaign” refers to a stable group of roughly half a dozen players. And, in point of fact, they refer to a style of gaming quite distinct from that found in most of the published modules from TSR.

OPEN TABLE: The first distinction of classic play is the open table. When Arneson and Gygax talk about a single campaign involving fifty players, they don’t mean that they lived in mansions with massive gaming tables where 50 players could huddle around a battlemat.

Under the open table model of gaming, the adventuring party was fluid. This Saturday your companions might by Bob, Steve, and Lucy. Next Tuesday it might be Steve, Suzanne, Ben, and David. And then on Wednesday you might get together with the DM for some solo play.

This kind of mass participation in a single campaign had a significant impact on how scenarios were designed: The dungeon complex was never designed to be “cleared” or “won”, because if you cleared the dungeon complex where was Tuesday’s group going to go?

And this extended beyond dungeon play. The entire campaign world was a limitless sandbox made interesting not only through the creative faculties of your DM, but also through the actions of your fellow players.

OPEN DMING: Both Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign and Gygax’s Greyhawk campaign featured co-DMs who would run adventures within the same setting and for the same players. For example, Rob Kuntz, who receives special thanks on the title page of Men & Magic, is known for having become Gygax’s co-DM for Castle Greyhawk and co-designing several levels of that infamous dungeon.

It was also common for characters to adventure in both Arneson’s campaign (which was based in Minneapolis) and Gygax’s campaign (which was based in Lake Geneva). And this kind of “campaign visitation” was common.

In fact, my gaming buddies and I used to do the same thing when we started playing: We each had our stable of personal characters, and these characters would be used interchangeably in all of the campaigns we would run (and we all had our own campaigns).

(On a tangential note: Some people ascribe this style of play as having been lost in the mists of time, but I’m not sure that’s actually true except on a personal level. Certainly as I started to place a higher value on verisimilitude and coherent character arcs, the “illogical” nature of campaign-swapping meant that I abandoned this style of play. But on those rare occasions when I’ve seen younger players, they often have the same carefree style of freeform gaming that I used to have.

So if this is something that you miss or that you want to have again, consider simply embracing it anew.)

MULTIPLE CHARACTERS: Part and parcel with all this is that it was apparently fairly typical for players to have more than one character playing in the same campaign. Sometimes they would be playing them simultaneously, but it was also quite typical for you to be playing one set of characters on Wednesday and a different set of characters the following Monday.

BEYOND DUNGEON-CRAWLING: You know what I’m tired of hearing? That D&D is a game about “killing things and taking their stuff” and nothing else.

Has combat and treasure-hunting always been a part of the game? Sure. But the game is about a lot more than that, and it always has been. For example, here’s the description of the fighting-man class from Men & Magic:

Fighting-Men: All magical weaponry is usable by fighters, and this in itself is a big advantage. In addition, they gain the advantage of more “hit dice” (the score of which determines how many points of damage can be taken before a character is killed). They can use only a very limited number of magical items of the nonweaponry variety, however, and they can use no spells. Top-level fighters (Lords and above) who build castles are considered “Barons” (see the INVESTMENTS section of Volume III). Base income for a Baron is a tax rate of 10 Gold Pieces/inhabitant of the barony/game year.

The idea that successful characters were destined for more things than dungeon-crawling was part and parcel of the game. There are rules in OD&D for stronghold construction, political assassination, the hiring of specialist tradesmen, baronial investments (in things like roads, religious edifices, and the like), assembling a naval force, and so forth.

And when you realize that this type of “realm management” play was an integral part of the original gameplay of D&D, then tables in which “40 – 400” goblins were capable of appearing begin to make sense: Sometimes you were a bunch of 1st level nobodies trying to root out the local goblin gang that had taken root in hills north of the village. And sometimes you were a band of nobles riding forth at the head of your host to wipe out the goblin army marching on your barony.

Now take a moment, if you will, and consider the type of game that arises when all of these elements are true: Some of the PCs have become the local nobles. Others are still lower level dungeon-delvers. And the entire world is developing and evolving as a result of their cumulative actions.

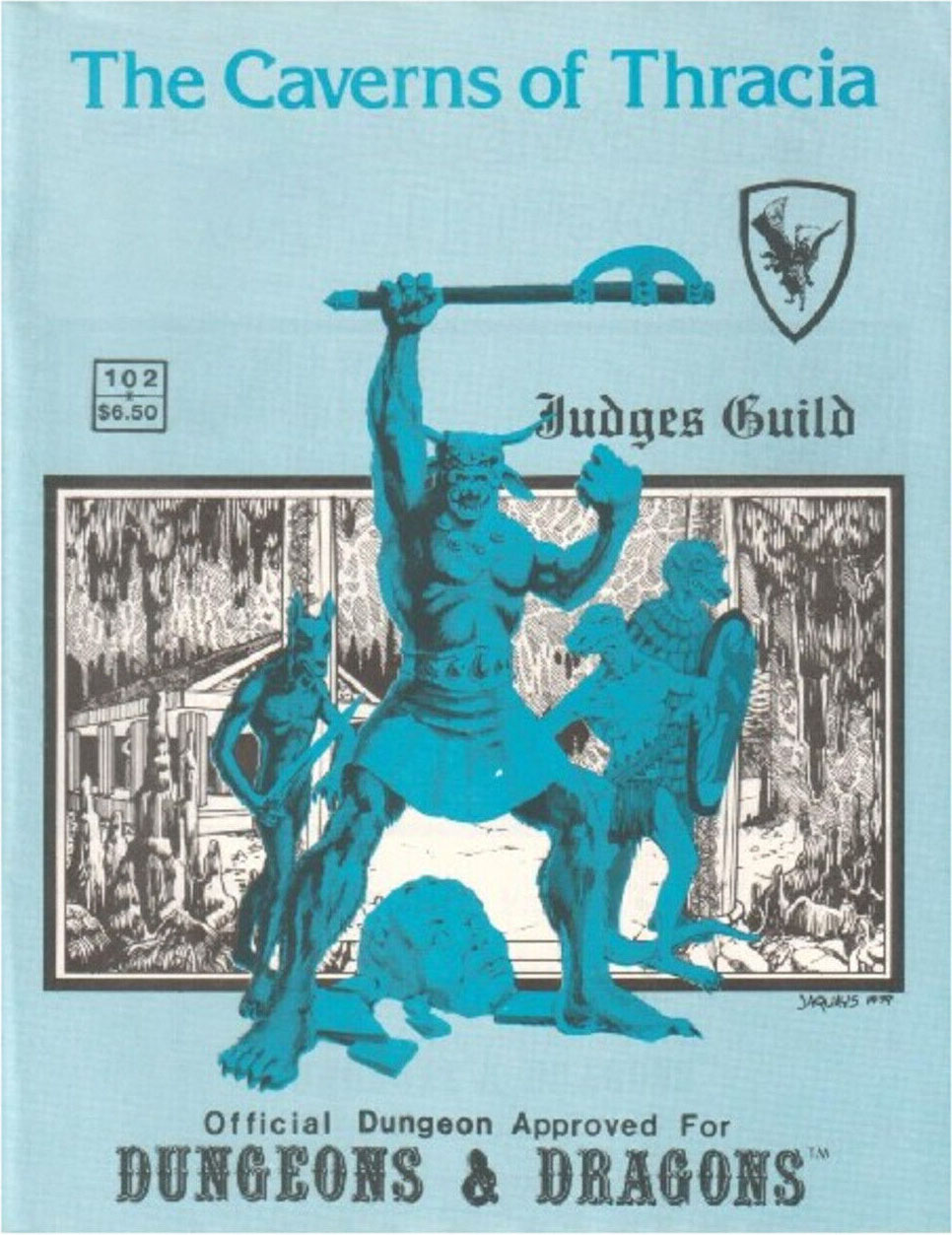

OFFICIAL SUPPORT

Ironically, this style of play never received any meaningful support from TSR. Not even in its earliest days. Have you ever seen a module with 400 goblins in it? There are a few glimpses of it here and there — in the Wilderlands campaign setting from Judges Guild or B2 Keep on the Borderland. But for the most part, the type of game being played by Arneson and Gygax — the type of game that led to the codification of the D&D rules — was not the type of game that was being supported through published modules.

Partly this is because that style of game is organic in its nature. You can’t actually capture the essence of the Greyhawk or Blackmoor campaigns, for example, because they were always evolving. (When Wizards of the Coast published Jonathan Tweet’s Everway, a member of the company memorably said something to the effect of, “If we could just include a copy of Jon in every box, we’d sell a million copies.” They couldn’t and they didn’t.)

But, on the other hand, that shouldn’t stop you from publishing the raw material from which a rich sandbox campaign could be played. But the Wilderlands campaign from Judges Guild is probably as close as we’ve ever gotten to that.

What stood in the way? Well, partly the resources. Publishing such a product in a single volume would have been a huge investment. And by the time TSR was capable of pursuing such an investment, that style of play was already becoming “outdated”, Arneson was long gone, and Gygax was already beginning to lose his control of the company.

And even if the resources had been available, such an undertaking would constitute an incredibly large and complex project. Gygax himself spent 30+ years trying to get Castle Greyhawk into print. It has never happened.

So what got published instead? Tournament modules. The earliest TSR modules — stuff like the A series, G series, and S series that we now think of as classics and defined the concept and format of what a “module” is — were all designed for tournament play. And tournament play is almost precisely the opposite of the type of game that Arneson and Gygax were running: The scope is limited (because you have to finish it within a single convention slot), the outcome premeditated (because the next round of the tourney was already designed), completion anticipated (so that scoring could be done), and the impact to the wider world nonexistent (because there was no wider world that could be effected).

For better or for worse, those were the modules that the gamers at home were buying. And they became the models around which their games were fashioned.

And, hand-in-hand with that, the mechanical support for those styles of play were purged from the rulebooks. 3rd Edition — designed by old school grognards working for a company which was, at the time, run by another grognard — saw a return of some of that lost mechanical support. But 4th Edition, of course, has reversed course once again.

The designers of 3rd Edition understood the value of open-ended, fully-supported play. You can see it in Ptolus (the campaign setting Monte Cook used to playtest the 3rd Edition rules). The designers of 4th Edition, on the other hand, openly proclaimed that the game was all about killing things and cited that getting back to those “roots” was one of their primary design goals.

Talk about your false premises.

This time the random 1d8 roll determined that they would be approaching the ruins from the southwest. As a result, they ended up practically stumbling over a short, squat building of gray-black stone that was hidden within a small copse of trees. A rusty gate on one side of the building led to a narrow flight of stairs that plunged down into darkness.

This time the random 1d8 roll determined that they would be approaching the ruins from the southwest. As a result, they ended up practically stumbling over a short, squat building of gray-black stone that was hidden within a small copse of trees. A rusty gate on one side of the building led to a narrow flight of stairs that plunged down into darkness.