It’s time to discuss a topic which is surprisingly contentious: Should the GM tell their players the target number of a skill test?

(Seriously. Go to any online RPG forum, ask this question, and watch the long knives come out nine times out of ten.)

My personal approach to open and hidden difficulty numbers is to consider them a tool rather than an ideology, with their use being a blend of utility and practicality. What information in the game world does the difficulty number represent and does the character have access to that information?

- If the difficulty number represents something that the PCs can directly observe, tell the players the target number of the check. (An easy example would be the difficulty of jumping over a crevasse: The character can actually see the crevasse and make a pretty good guess about how difficult it is. Telling the player helps give them a clarity similar to their character’s vision.)

- If the difficulty number represents something that the PCs can’t observe, keep the number hidden from them. (For example, they’re walking through a jungle and I want to know if they spot a tribesmen hiding in the canopy above them. The difficulty of the spot task is based on how good the tribesmen are at hiding. Does the PC know how good the tribesmen are at hiding? No. They don’t even know it’s tribesmen they’re trying to spot. Therefore, they don’t get the target number.)

- If you’re feeling tricksy, you can give the players an estimated difficulty number based on what their PC does know and only reveal the real difficulty number when they’ve realized their error. (“The guy is standing nude in the middle of the field. Should be really, really easy to hit him…” “Your shot bounces off the force field surrounding him. This might be trickier than you thought.”)

When in doubt, I will generally default to not telling the players the target number. But this default position can be flipped in some systems for reasons of practicality. For example, in Call of Cthulhu you apply difficulty to the character’s skill rating and then attempt to roll under the modified rating. I’ve found it’s generally easier to give the players the difficulty modifier and have them simply report their success or failure rather than getting them to report a margin of success that I can then compare to the difficulty rating. (Your mileage may vary here, obviously.)

In addition to simple practicality and efficiency in game play, my method is influenced by a couple of factors. First, there is a limited bandwidth by which the players perceive the game world compared to their characters: They are relying almost entirely on imprecise verbal descriptions, whereas their characters have access to their full panoply of sensory input. While it is true that their characters cannot necessarily measure their chance for success at a task with mathematical certainty, I find that this nevertheless achieves more associated results than characters, for example, leaping over crevasses that no sane person would attempt if they could actually see it with their own eyes. Open difficulty numbers reduce the frequency with which there is miscommunication between the GM and the players, which can help minimize the old Are you sure you want to do that? problem.

Second, there are many circumstances in which the players will be able to figure out what the target number is. (Multiple characters making attacks against a fixed armor class, for example.) In some cases this experience can be very immersive (as the characters slowly figure out just how skilled their dueling partner is before declaring that they’re not actually left-handed, for example). But that also makes it an example of how knowing a difficulty number doesn’t instantly implode the table’s immersion, and even in circumstances where difficulty numbers are initially hidden, it can often make sense to explicitly lift the veil of mechanical secrecy after a short period of time in order to facilitate the practicality of speeding up play.

RESOURCE SPEND GAMES

Over the last decade or so we’ve seen a proliferation of RPGs featuring mechanics where the players will spend points from a limited pool as part of a skill test. GUMSHOE and the Cypher System offer one common form, with points being spent from skill or attribute pools in order to provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

I’ve found that these types of systems — particularly the GUMSHOE and Cypher System variety — require some special attention when it comes to open vs. hidden difficulty numbers. Blindly spending limited resources on tasks with unclear difficulties generally doesn’t seem to work well in these types of systems: Players often get frustrated and resources are generally overspent, which can rapidly propel a session towards the hard limits of the system and really limit effective scenario design.

Which is not to say, of course, that difficulty numbers should NEVER be unknown in such games. The occasional spice of an unknown search test, for example, can be really rewarding: The player doesn’t know if there’s anything hidden in the room or how valuable it may be, so they have to make a tough choice about exactly how much effort they’re going to put into searching it. When facing a previously unknown creature, they have to make a choice about snapping off a shot or really taking the effort to aim. That’s immersive and effective.

But if the whole game is cloaked in perpetual mystery, it’s much less effective in practice. It muddies decision-making (particularly in these resource spend games) and hurts immersion.

Another way of looking at this is that there is a “threshold of knowledge” at which the GM deems it appropriate to reveal the difficulty number. This threshold, however, is basically a slider. What I’m suggesting is that for these resource spend mechanics you want to radically reduce your threshold (particularly if you normally keep it relatively high).

For these resource spend games I have also coined the term “routine check” so that I can still call for things like routine Perception tests to determine which character spots something first without having everyone burn away their resource points, uh… pointlessly.

UNCERTAIN TASKS

Traveller 2300 included an interesting resolution method that I have never seen reproduced elsewhere, but which can be trivially adapted to virtually any RPG system. For any uncertain task, in which the actual success or failure of the outcome may not be immediately clear to the character (such as gathering information, convincing someone to help you break the law, or repairing a buggy piece of equipment):

… both the player and the referee roll for success (the referee rolls secretly). If both are unsuccessful, the referee provides no truth. If one is successful and the other is unsuccessful, the referee provides some truth. If both are successful, the referee provides total truth. In all cases, the referee does not indicate whether the answer or information provided is truth, some truth, or total truth.

A result of no truth means the character is totally misled as to the success of the attempt. Completely false information is given.

A result of some truth means the character is given some idea of the success of the attempt. Some valid information is given.

A result of total truth means the character is not misled in any way as to the success of the attempt. Totally correct information is given.

Because of the hidden nature of the referee’s throw, the character cannot know for certain the nature of the information being obtained. A referee may find characters doubting total truth, accepting some of no truth, or accepting all of some truth.

Marc Miller, the leader designer for Traveller: 2300, wrote about this mechanic in “Traveller: 2300 Designer’s Notes” in Challenge Magazine #27:

Setting fuses for demolitions is an uncertain task contained in the Traveller: 2300 rules. It is classified as easy, and anyone with any skill will usually succeed. Once in a while, the referee will roll a failure while the player succeeds: somehow the fuse setting failed (although it looks OK) and the explosive won’t detonate when the proper time comes. And once in a while, the player will roll a failure (and immediately realize that he has wired the explosive wrong), he can rewire them immediately to try to fix the fault. And sometimes, the player will roll a failure and hear the referee tell him the charges have exploded – because the referee also rolled a failure.

This method is an incredibly clever way of reintroducing uncertainty into the player’s (and character’s) perceptions even when embracing the practical advantages of player rolls and open difficulty numbers. I think it deserves to be much more widely known and used.

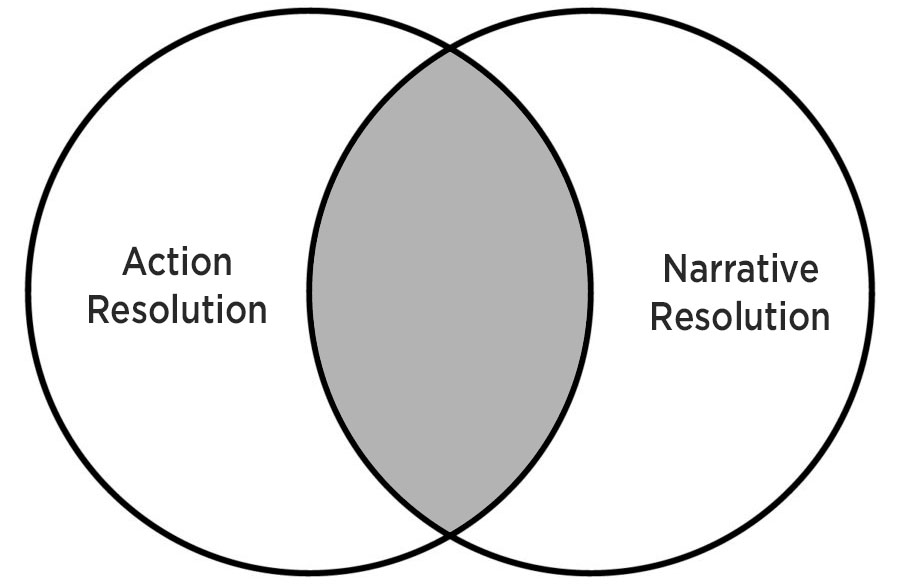

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.