The story has become a legend in the roleplaying industry.

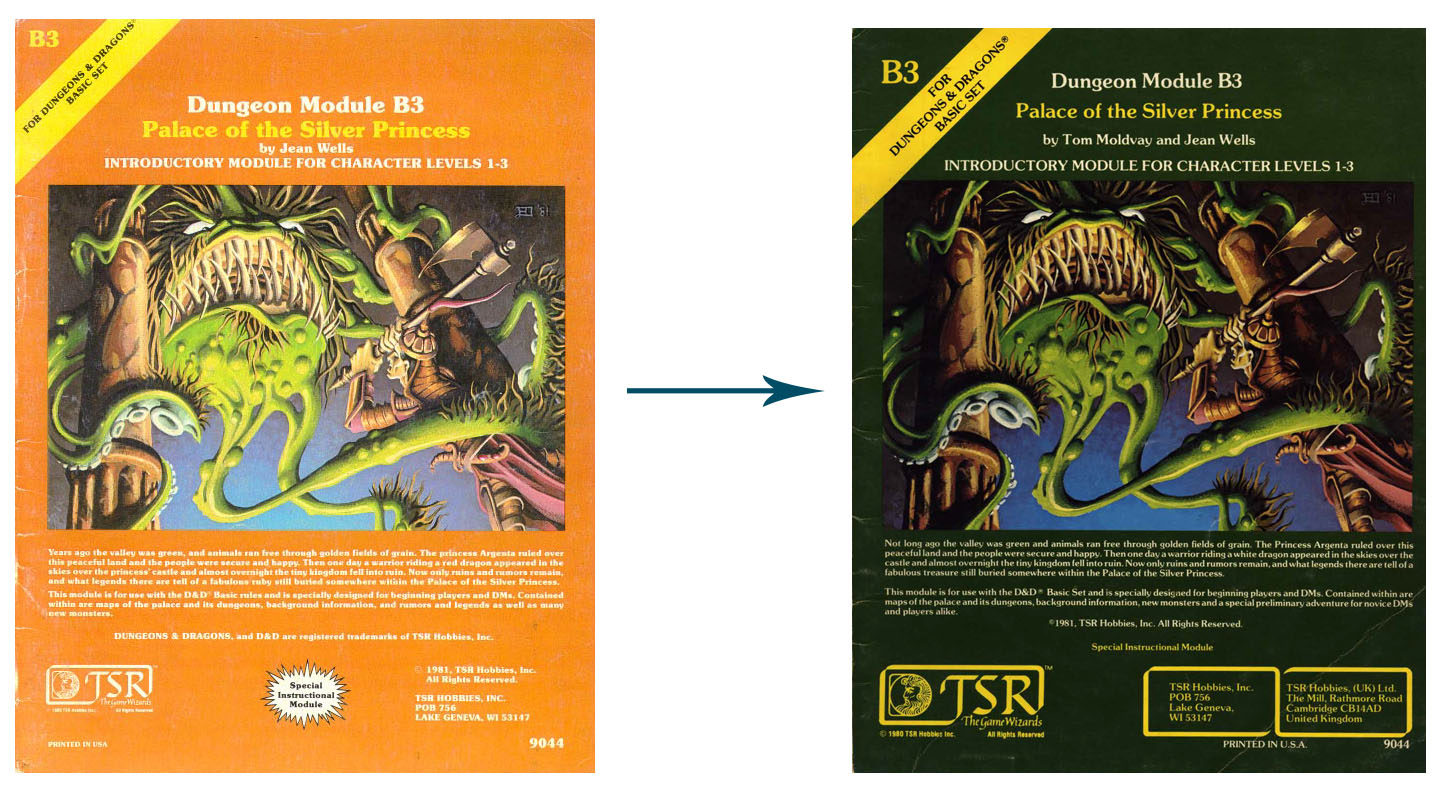

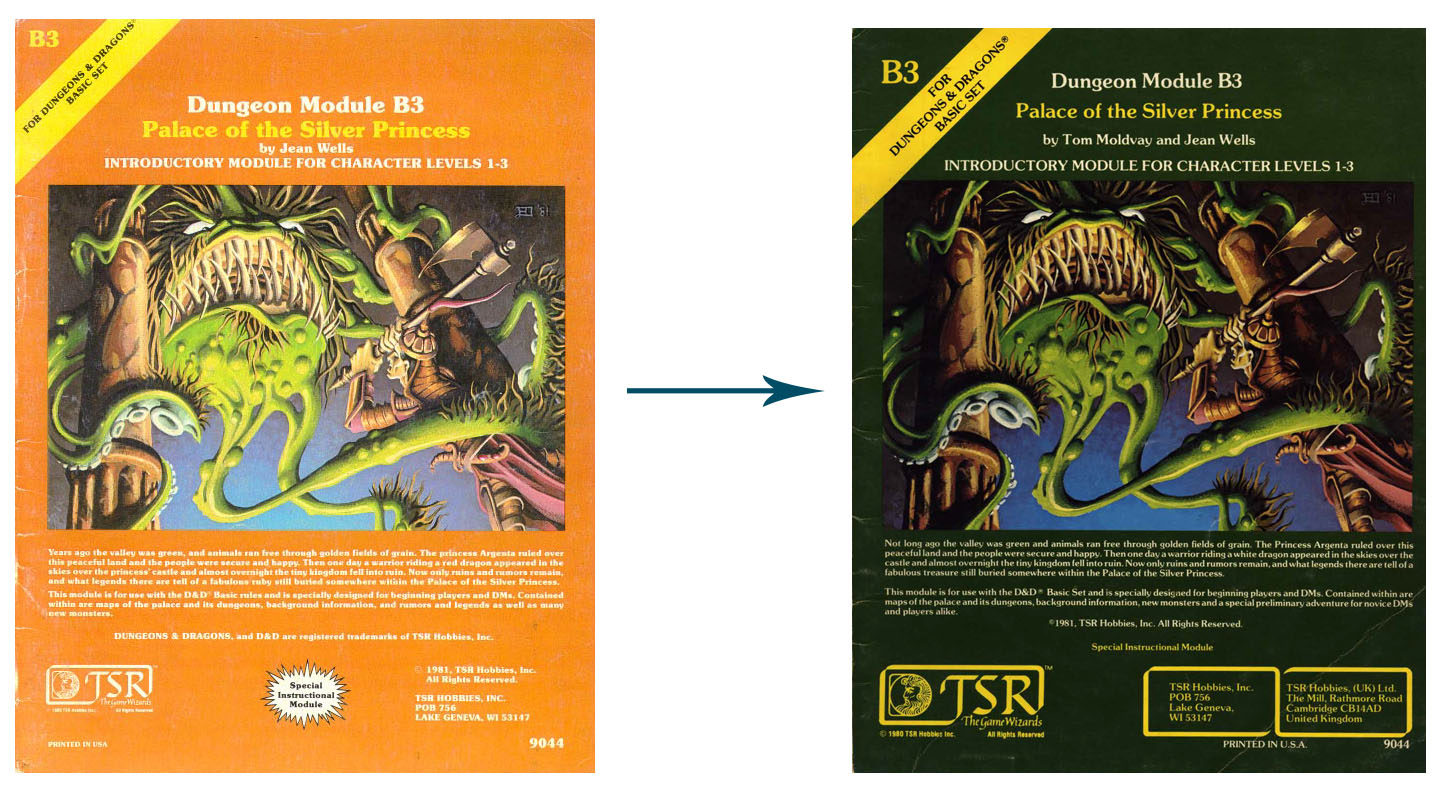

In 1981, TSR was preparing to release module B3 Palace of the Silver Princess. Written by Jean Wells, it would have been the next module in a series that had already produced the classic B1 In Search of the Unknown and B2 Keep on the Borderlands (although both of those had benefited from being included in versions of the D&D Basic Set). The module had, in fact, been printed and was ready to be shipped out to distributors. Comp copies were distributed to all of TSR’s staff.

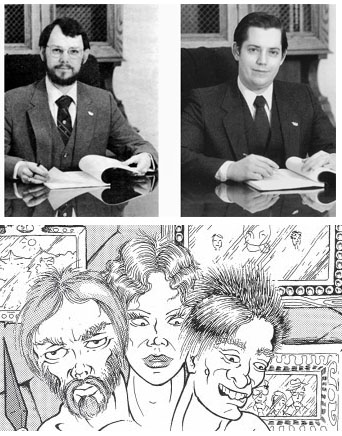

And that night, the story goes, a senior executive flipped through their copy of the module and then flipped the fuck out when they saw this piece of art:

When I first heard the story in the early ’90s, it was supposedly a fully nude woman, but you can see that’s not the case. Nevertheless, according to the story, the senior executive deemed this art to be Too Risque(TM) for the newly family-oriented Dungeons & Dragons product line. He ordered the product line pulped and even went so far as to go stalking through the staff cubicles that night, yanking the complimentary copies that had been distributed so that they, too, could be destroyed. The only copies which survived were those in the hands of the few staff members who had taken their complimentary copy home with them that afternoon. The offending picture was replaced, the cover was turned from orange to green, and the whole thing reprinted.

It’s a good story. As an urban legend, I suspect it became even more popular once Lorraine Williams took control of the company and they went all-in on making D&D family-friendly (eliminating the words “demon” and “devil,” for example). Around 2003, it even became ensconced as official history when Wizards of the Coast posted a history of the module on their website.

The only problem is that once you can actually look at the original version of B3 Palace of the Silver Princess, the story doesn’t actually make much sense.

If you deemed a piece of art so offensive that you needed to pulp the entire production run and reprint, then you would simply replace the offending piece of art and do the reprint. But that’s not what happened here: Instead lots of different pieces of art were removed or redrawn and Tom Moldvay was brought in to substantially rewrite the entire module.

Over the years, this has led a number of people to go looking for the real piece of art that was at fault. Or to explain why each specific piece of art that was removed had been deemed “problematic” by that anonymous executive all those years ago. For example, I’ve read no less than two essays trying to figure out why this picture of a tinker’s wagon was removed:

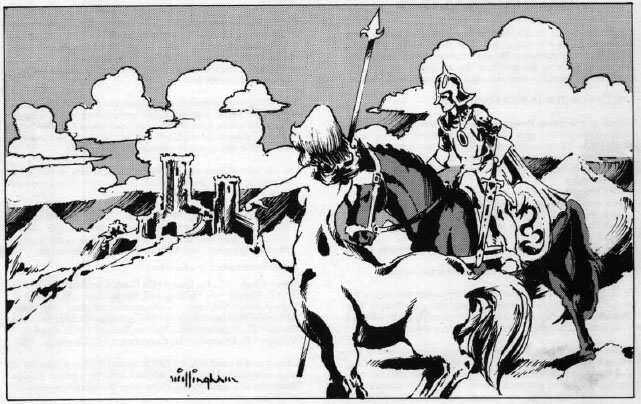

And if you were looking to remove all the salacious art in the module, it sure seems weird that the topless centaur on the title page somehow survived the purge:

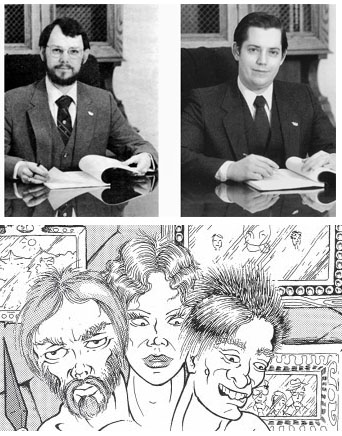

In 2009, Frank Menzter offered a fresh version of the story in this vein: The real piece of art that had caused the uproar wasn’t “The Illusion of the Decapus,” it was a picture of the three-headed giants called ubues drawn by Erol Otus. Two of the ubue heads looked just like the Blume brothers, and that’s why Brian Blume, TSR’s Vice President, pulped the module.

Frank Menzter was actually there, of course, and so this quickly became widely retold as the real story of what had happened.

Some people noticed, though, that Mentzer didn’t actually know. He was reporting thirty-year-old office gossip, and there was the slight problem that the ubues didn’t actually look like the Blume brothers unless you squinted really, really hard:

Watching the urban legend metastasize at this point is actually kind of fascinating. Mentzer’s identification of the ubue art combined with the older salacious art version of the story, and people now pointed to the three-breasted ubue elsewhere in the image as the real source of the controversy. Others identified the third head on the supposed Blume-ubue as being Lorraine Williams. The legendary appeal of this was obvious, as the Blume brothers and Lorraine Williams were most popularly known in RPG lore as the “villains” who “stole” Gygax’s company from him. It would also make Erol Otus a time traveler, since Lorraine Williams was not even associated with the company yet in 1981.

Shannon Appelcline would later revisit this history and, based on different sources inside TSR, conclude that it was actually Will Niebling and maybe Kevin Blume responsible for the recall.

PASSING OF AN ERA

There may be some kernel of truth to all this: Some piece of art that tweaked some executive’s sensibilities and triggered the recall.

But whether that’s true or not, it’s fairly clear that once a reprint was greenlit somebody (or possibly a whole committee of people) decided that there was substantially more wrong with the module than a single image. As I mentioned, Tom Moldvay was brought in to perform a radical rewrite, and while large chunks of Wells’ original draft remained intact, the entirety of the module was drastically transformed.

And it is, in fact, this transformation that I want to call particular attention to. Because while others point to Dragonlance or Ravenloft or 2nd Edition, I think that if there is one singular moment you can point to and say, “This is when the old school died,” then it was when that nameless TSR executive went crawling through the cubicles, snatching copies of Wells’ module to destroy.

Before diving in here, I also want to discourage people from interpreting this as some sort of full-throated assault on Tom Moldvay’s revisions. The published version of B3 Palace of the Silver Princess was actually a really seminal influence on me as a young DM and probably the single most important module I bought for D&D: I found a used copy of it in Pinnacle Games in Rochester, MN just a few months after buying Mentzer’s red-boxed Basic Set and its expansive dungeon clicked for me as the platonic ideal of D&D in a way that the cramped caves of B2 Keep on the Borderlands did not at the time: I read it cover to cover multiple times. I ran it for my friends over and over and over again. Even the art probably had an out-sized influence on my vision of D&D fantasy for many years.

(Even — or perhaps especially — that now painful-looking centaur side-boob. Seriously. Imagine galloping around without a bra.)

I’m not going to discuss every single change that was made in the module, but I do want to look at a few broad examples that show the radical transition from old school to new school design in the revision of a single product. If you want to do your own side-by-side comparison, you can do so by snagging a copy of the green cover edition from the DM’s Guild and a copy of the orange cover edition from the Internet Archive copy of Wizard’s old D&D pages.

THE END OF THE SANDBOX

The very first substantive change in the module probably captures the fundamental ideological shift in the revision. Jean Wells wrote:

The information given below should be read carefully. Part of it can be given to the players. It will be up to the DM to decide exactly what the players should know about the palace. This information can be altered if desired. The DM is encouraged to add whatever he or she wants to this information to give more color to the palace.

Wells then discusses several cruxes that the DM will want to make decisions about before running the adventure.

Moldvay, on the other hand, abandons this approach, replacing it with a big slab of boxed text labeled, “Player’s Background (Read to players).”

As you look at the two versions of Palace of the Silver Princess, this is the core of it: Jean Wells is presenting a toolbox full of cool material and, in the classic old school style, challenging the DM to make it their own; to take the toolbox and do awesome things with it. Moldvay’s version of the module is a prepackaged experience.

For example, in Wells’ version of the module, the fall of the Palace of the Silver Princess is an ancient legend. The tragedy happened long ago and its participants — like Princess Argenta, the Dragonrider, and the strange ruby known as My Lady’s Heart — have become legend. What’s left behind is a moldering ruin for the PCs to explore or ignore.

In Moldvay’s version, however, the palace was attacked mere weeks ago and the PCs are given a specific quest by a quest-giver to go and save the day:

Each player character has had the same dream. In the dream, a Protector came to the person and pleaded for help.

“Haven is in dire trouble,” the Protector said. “We do not know what caused the disaster, but we do know that the reason can be found somewhere in the palace. (…) You are Haven’s only hope. We beg you find the source of the evil that has overtaken Haven, and destroy that evil.”

Thus a sandbox is systematically transformed into a potted plot.

THE END OF THE OLD SCHOOL DUNGEON

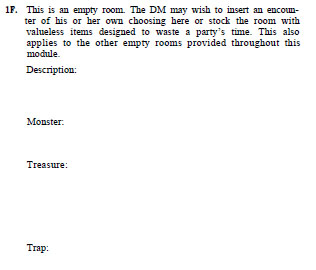

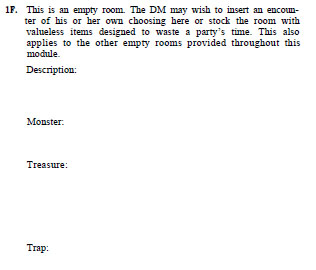

Wells also embraces a technique that Mike Carr pioneered in B1 In Search of the Unknown by leaving certain rooms unkeyed:

But there are two significant differences to Wells’ use of this technique.

First, Mike Carr’s empty “Monster:” and “Treasure:” fields were paired to a specific list of pregenerated monsters and treasures that the DM was supposed to simply assign to the various rooms. It was a training wheels approach to teaching DM’s how to key rooms and, importantly, demonstrating through practice how stocking rooms in different ways could lead to different play experiences.

Wells gave the beginning DM the same blank canvas, but without the pregenerated content to fill it. They would need to make up the content on their own. If you look at the B series of modules as an instructional course, this was a logical progression to what new DMs had learned and done in the earlier installments.

The other notable thing about Wells’ use of the technique, though, is that she only used it for explicitly empty rooms. While the DM was given the space to fill these areas, there was no expectation that they would or even should fill all of them before using the module. This, first, emphasizes the importance of negative space in old school dungeon design. But it also, and more importantly, emphasizes that dungeon keys are designed to evolve and change over time: These rooms are empty now, but perhaps they will not be the next time the PCs come here.

Whereas Moldvay’s dungeon was a use-once-and-done plot, Wells was designing an old school dungeon with the expectation that it would be visited again and again.

If you want another example of how misinformation can be spread, check out Rateliff’s claim on that old Wizards of the Coast page I linked to above:

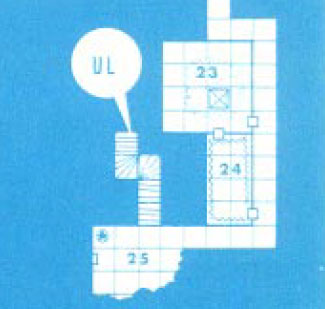

More significantly, Moldvay fixes a significant flaw in the original, explaining how the princess got upstairs in her own castle by adding a main staircase (area 22 in the “green cover” edition).

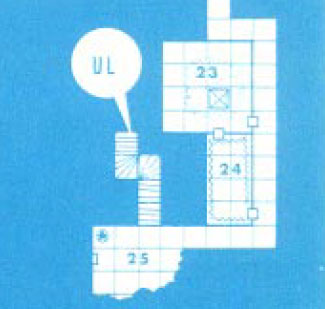

Mentzer repeats this claim in his 2009 account (“like a missing important stairway”). But (a) the stairs in area 22 of Moldvay’s version don’t go upstairs, they go outside; and (b) there is no missing staircase in Wells’ version. The stairs to the Upper Level (UL) are clearly labeled and keyed:

It is actually Moldvay who removes these stairs, leaving the only route to the upper level a trapdoor in the floor of a guard tower (areas 48 and 49 in his version; areas LL-38 and UL-1 in Wells’).

And this change is actually really significant, because the effect is to de-xander the dungeon: Because Moldvay’s dungeon is a plot, he needs a more linear experience with the final fight located at the “end” of the dungeon. Moldvay’s dungeon is, in his own words, designed to be “completely explored” (albeit not in one night). By contrast, in the very first paragraph of the module — basically the very first instruction she gives to the reader — Jean Wells says, “To expand the dungeon, the DM need but open up the blocked passageways and add new and challenging dungeon levels.”

THE SPIRIT OF ’74

Although Wells goes on to say that “this should be done only after most of the encounter areas have been explored,” what she’s actually describing is exactly in line with what Arneson & Gygax described in the original 1974 edition of the game:

Before it is possible to conduct a campaign of adventures in the mazey dungeons, it is necessary for the referee to sit down with pencil in hand and draw these labyrinths on graph paper. Unquestionably this will require a great deal of time and effort and imagination. The dungeon should look something like the example given below, with numerous levels which sprawl in all directions, not necessarily stack [sic] neatly above each other in a straight line.

In beginning a dungeon it is advisable to construct at least three levels at once, noting where stairs, trap doors (and chimneys) and slanting passages come out on lower levels…

Three levels is, in fact, what Wells provides with a lower level, an upper level, and a tower level. In addition to her instruction to expand the dungeon at the beginning of the module, she includes an appendix with new encounters that can be used to both restock the dungeon and expand it. On her maps she includes almost a dozen collapsed tunnels, and calls out specifically in the key of each of these areas that, for example, “This area may be opened up by the DM.”

(To be fair, the vestigial remnants of all this is preserved in Moldvay’s version in the form of a single blank sheet of graph paper which states, “This graph paper is provided so that the DM may expand the module, if desired. Possible areas of expansion include lower caverns such as areas 11, 17, 20, 45, etc.”)

Arneson & Gygax also wrote in 1974:

The so-called Wilderness really consists of unexplored land, cities and castles, not to mention the area immediately surrounding the castle (ruined or otherwise) which housed the dungeons. The referee must do several things in order to conduct wilderness adventure games. First, he must have a ground level map of his dungeons, a map of the terrain immediately surrounding this, and finally a map of the town or village closest to the dungeons (where adventurers will be most likely to base themselves).

This ideology is why Wells’ version of the module features a region map accompanied by a small gazetteer, rumors, and random encounters: She’s designing the sandbox that the original edition of D&D had instructed you to design. (All of these elements would be removed from Moldvay’s version.)

THE LOST MEGADUNGEON

I would argue that if the original version of B3 Palace of the Silver Princess had actually been released, it would have been the closest TSR ever got to publishing a true Arnesonian megadungeon like the one described in the original edition of D&D. Not because it had a dozen levels all mapped out, but because it was designed to be the essential seed of a megadungeon campaign.

As I mentioned earlier, the published version of B3 was a mainstay of my first couple years of playing D&D. Back when I was running my first OD&D open table, one of my players spontaneously asked to play during a game night. I was pretty drunk, so I decided not to pull out my full kit for the campaign. Instead, I grabbed B3 Palace of the Silver Princess off the shelf and decided to run it as a shout out to my glory days. But I actually had a copy of both versions of the module, and I decided — in a moment of either inspired genius or utter madness — to run both versions of the module at the same time.

As the PCs explored the dungeon, they kept flipping back and forth between the orange-covered version of the module (when the catastrophe had happened long in the past) and the green-covered version of the module (when the catastrophe was fresh and new). The changes to the map and the weird temporal artifacts both confused and excited the players, who later demanded to return and continue their explorations. As a result, I ended up adding the Palace to my open table campaign setting.

It was during this time that I re-read both versions of the module in full… and realized the “lost megadungeon” of Wells’ module. As a result, I decided to open up those blocked passageways and connect them to the upper levels of the Castle of the Mad Archmage, instantly turning the whole thing into the megadungeon it had always been meant to be. I anticipated that the Palace would join the Caverns of Thracia as a second megadungeon tentpole in the campaign.

Sadly, that never happened: The PCs turned their attention from the Palace to hexcrawling, and the campaign eventually ended before anyone found those passages leading down into the depths.

But I suspect this is an idea that I will return to in the future. Perhaps it’s a journey you’ll join me on.