Go to Part 1

Let’s start by taking a look at some of the basic techniques you can use while creating non-linear dungeons.

Some of these techniques are designed to offer complex geographic relationships (out of which meaningful choices can naturally arise). Others are designed to confuse the mapping of the complex (or, even in a game dynamic without player mapping, to confound their general understanding of the complex). The point is not (necessarily) to create a maze-like environment, but rather to create an environment of sufficient complexity that the “hand of the author” and the underlying structure of the dungeon environment become obfuscated.

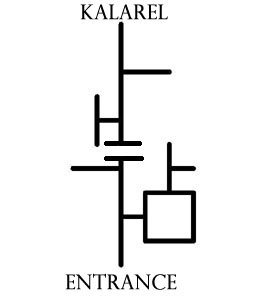

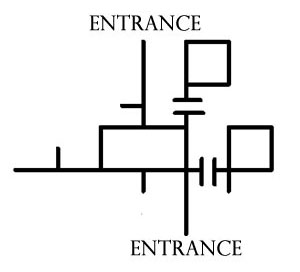

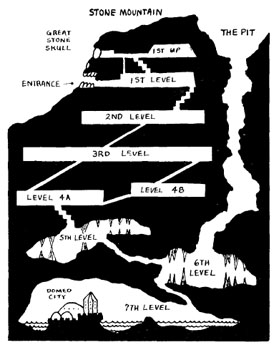

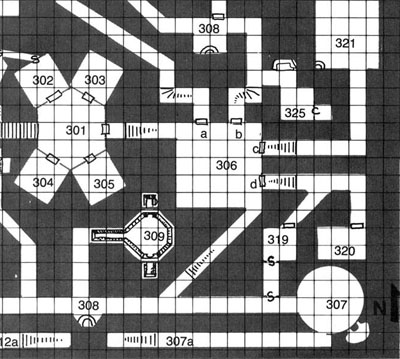

MULTIPLE ENTRANCES: Multiple entrances give the PCs an immediate strategic choice as they approach the dungeon complex. Hidden secondary entrances also reward exploration both inside and outside of the dungeon, allowing for favorable approaches and quick escapes. In terms of structure, multiple entrances effectively create an additional “loop” (see below) through the surface above the dungeon.

For example, consider the classic Stone Mountain dungeon from the 1977 D&D Basic Set, designed by Tom Moldvay and Tom Wham:

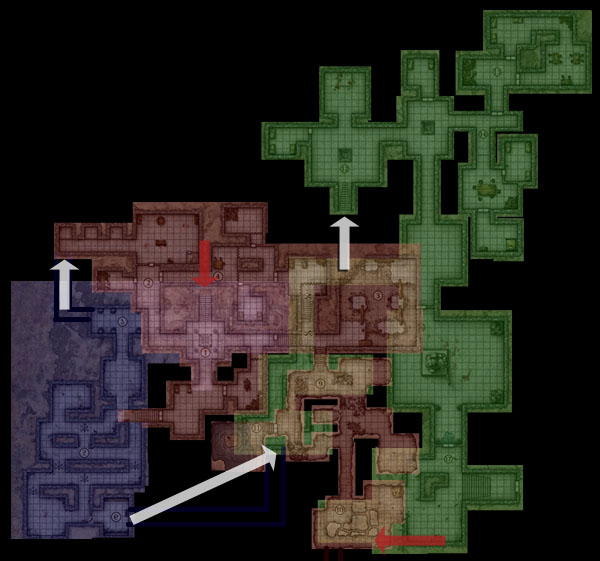

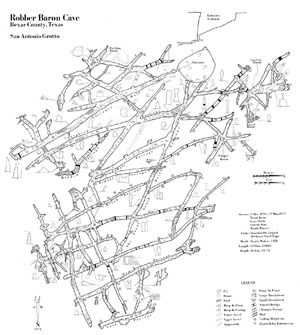

LOOPS: Branching paths in a dungeon allow for choice, but are still functionally linear in their design. (In practice, you will follow a branch to its end; backtrack; and then go down a different branch. But each branch still presents a linear experience.) Where things get interesting is when you grab a couple of those branches and hook them together into a loop. These loops are the basic building blocks for non-linear dungeons: They provide meaningful strategic and tactical choices; make exploration meaningful; and allow PCs to find alternative routes around or through potential threats.

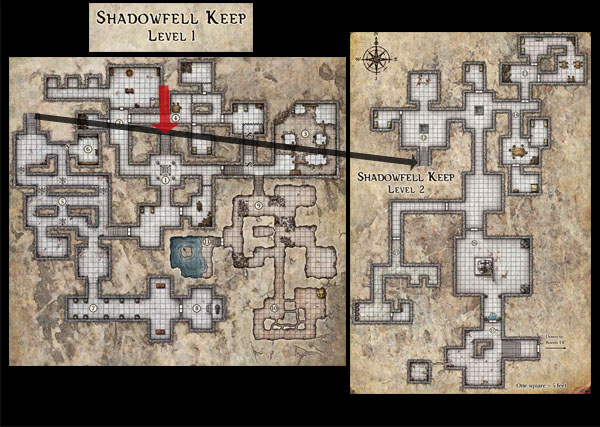

MULTIPLE LEVEL CONNECTIONS: If there is only a single route leading to the next level of the dungeon the complexity of the current level is collapsed into a chokepoint. But if you introduce multiple connections between the dungeon levels you create a synergy between complex level designs. Just as you create new structural loops by including multiple entrances to the dungeon, each additional connection you draw between levels creates new looping paths through the dungeon.

DISCONTINUOUS LEVEL CONNECTIONS: In a linear design, the levels of a dungeon must proceed in their predetermined order: Level 1 leads to Level 2. Level 2 leads to Level 3. And Level 3 leads to Level 4.

But once you introduce multiple connections between levels, you are free to have some of those connections skip levels. For example, there might be an elevator on Level 1 that takes you down to Level 3. Or a hidden tunnel on Level 4 that takes you back to the surface a half mile away from the dungeon’s main entrance.

SECRET & UNUSUAL PATHS: These are fairly self-explanatory. They reward curiosity and exploration, and can also breathe fresh life into areas of the dungeon which have already been traversed.

One thing to note is that not every secret path needs to take the conventional form of a camouflaged doorway: Tunnels that have suffered cave-ins. Traps that drop you to lower levels. Archaic teleportation systems that must be decoded. Rope bridges that cross over caverns that can also be explored from below. A submerged bypass connecting two seemingly unrelated lakes.

And here, too, you benefit from the non-linear design of the xandered dungeon: Because there are other viable paths for the PCs to explore, you can include truly esoteric, unusual, and flavorful paths that may be missed by the unwary (and, therefore, appreciated all the more by those who do discover them).

SUB-LEVELS: The distinction between a “level” and a “sub-level” is somewhat arbitrary, but perhaps the defining characteristic of the sub-level is that it departs from the main “sequence” of the dungeon. It may be smaller than the other levels of the dungeon; it may be difficult to reach; or both. As such, sub-levels serve as boulevards of discovery or elaborate shortcuts (or both).

DIVIDED LEVELS: Similar to the concept of a sub-level is that of the divided level. While existing within the main “sequence” of the dungeon, a divided level cannot be completely traversed without going through the levels above or below it.

For example, on the second level of the dungeon one might find two staircases both leading down to the third level. But on the third level itself, there is no path which connects the two staircases. (Or, if there is such a path, it may be incredibly well hidden or difficult to traverse.)

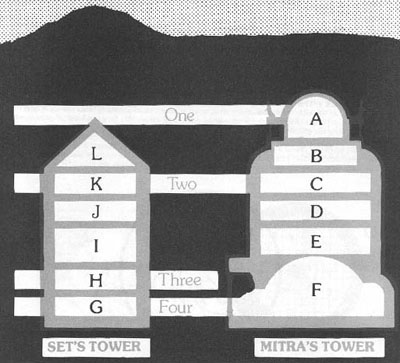

NESTED DUNGEONS: Nested dungeons are sort of like sub-levels or divided levels on steroids. Imagine designing two separate and distinct dungeon complexes, but then linking them together at selected locations. (For example, consider the Lost Temple of the Gorgons and the Obsidian Caverns as both being fully developed dungeon complexes, each with multiple levels and sub-levels. You could nest the Lost Temple within the Obsidian Caverns by creating two links between the complexes: A long passage on the first level of the former might lead to the third level of the latter. And a teleportation pad on the sixth level of the latter might lead to the fifth level of the former.)

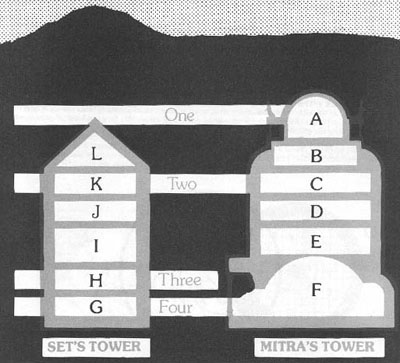

As a practical demonstration of this technique, consider Jaquays’ Dark Tower:

Both Set’s Tower and Mitra’s Tower are nested into the four primary levels of the dungeon.

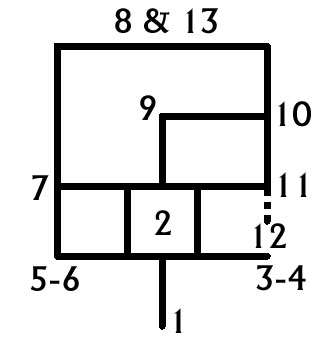

MINOR ELEVATION SHIFTS: When the PCs come to a staircase they may naturally assume that they are going up or down to a new level of the dungeon. But by including minor elevation shifts within the topography of a single dungeon level you can confound their expectations. Here’s an example from the Temple of Elemental Evil by Gary Gygax and Frank Mentzer:

In addition to short stairways and misleading slopes, you can also include tunnels that loop under each other while technically remaining on the same “level” of the dungeon. It’s also important to “think vertically” within rooms as well.

These techniques aren’t just a matter of confusing the players’ mapping. You are disrupting their ability to intuit the organization of your maps by analyzing the reality of the game world. While maintaining clean and simple maps for your own use and reference, you are creating a world that not only seems more dynamic and complex, but actually is more dynamic and complex.

Basically, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that just because your map is two-dimensional that the world should be two-dimensional.

MIDPOINT ENTRY: I don’t think Jaquays ever used this technique, but you can complicate the players’ approach to the dungeon by creating immediate bilateral exploration. In other words, PCs entering a dungeon are usually only faced with one navigational question at the macro-level: “How do we get down to level 2?”

But if the PCs are instead entering in the middle of the dungeon – with levels above and below them – then they’re first faced with a tougher question: “Which way do we go?”

Note that this decision point is similar to the one faced by PCs who have “skipped” a level as a result of a discontinuous level connection. It is also similar to the situation faced by PCs who have taken advantage of a hidden entrance leading to a lower level of the dungeon. The distinction of the midpoint entry is that it is the expected, default entry point to the dungeon. (And in classic dungeon arrangements, where difficulty corresponds to dungeon level, the difficulty of the dungeon would increase in both directions away from the midpoint entry.)

NON-EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY: If you want to have some real fun, consider using non-Euclidean geometry. These Escher-inspired designs can result in counter-intuitive navigation and may even result in PCs moving between levels without realizing that it’s happened. For examples of non-Euclidean design, check out my work on FFG’s The Lost Hunt and the award-winning Halls of the Mad Mage.

EXTRADIMENSIONAL SPACES: Sections of a dungeon complex may lead into areas completely beyond the dungeon itself while still remaining intimately tied to the dungeon’s topography and/or experience. For example, Gary Gygax’s EX1 Dungeonland module detailed a Wonderland-inspired demi-plane that could be accessed deep below Castle Greyhawk. I’ve read about another DM incorporating the lost island of X1 The Isle of Dread as a similar demi-plane within their megadungeon complex.

While such excursions can certainly breathe a little air into a claustrophobic dungeon delve, I think it remains an open question where the distinction between an extradimensional space which “belongs” to the dungeon and a teleportation effect which simply takes the PCs out of the dungeon entirely actually lies. In practice, the line between the two is probably more a blur than a distinct demarcation.

Laying aside these broader questions, I include extradimensional spaces in the list of xandering techniques because they also allow you to super-impose multiple areas into a single geographic space.

Next: The Philosophy of Xandering