Slay the Dragon! is a Polish RPG which is now being translated into English by Hexy Studios. They wanted to give me a sneak peek at what the game offers, and when I saw the treasure trove they’d sent, I knew I wanted to open that treasure trove with you!

RPG Flags: Wants vs. Warnings

There are plenty of RPG tips that look great on paper, but not at all when you bring them to the table. The really tricky ones, though, will work just fine… and then suddenly explode in a fiery ball of chaos and destruction.

The problem, of course, is that players, groups, and games are all unique. Something that works for one group may not work for another. It may not even work with the same group when they’re playing a different game. Or it may work for some players in the group, but not others.

For example, back around 2000 there was a brief fad for character flags: The clever insight was that if players put something on their character sheet or in their background, that was a signal — or “flag” — that it was something they wanted to be featured in the game!

In practice, unfortunately, this didn’t hold up. Turns out that just because you included “escaped from an abusive father” in your character’s back story, it didn’t necessarily mean you wanted the abusive father to show up in the game. Often quite the opposite.

Similarly, it turns out that many players will buy up a skill in character creation because they DON’T want that skill to be a significant part of the game: They invested a bunch of character creation resources to specifically NOT be challenged by it, wanting to quickly and trivially dispose of any such content if it does happen to show up.

Conversely, someone creating a character with a high Lockpicking skill might absolutely want lots and lots of locked doors to show up in the campaign… but only so that they can show off how awesome their character is by getting their LockpickingLawyer on and casually gaining access to every egress, treasure chest, and safe. If you were to instead respond to their lockpicking flag by creating lots of ultra-difficult locks that will challenge their high level of prowess, you’ll still end up with a frustrated player.

(And the point, of course, is that other players who have created a character with a high Lockpicking skill will want to be challenged by lots of very difficult locks.)

Recently I’ve seen a similar “GM trick” doing the rounds that I’m going to call Schrodinger’s secret door. The basic idea is that if the PCs are in a dungeon (or a gothic manor or whatever) and they look for a secret door, the GM should respond by adding a secret door to the room and letting them find it!

The idea, of course, is that when the players say, “Let’s see if there’s a secret door!” what they’re really saying is, “It would be cool if there was a secret door here!”

Which might be true.

But it can just as easily be, “I hope there isn’t, but let’s make sure before we use this room to take a rest.” Or simply, “Let’s test this hypothesis and see if it’s true.” (See The Null Result for more on that.)

It doesn’t have to be a secret door, of course. Maybe the players decide to run surveillance on their new patron to make sure they don’t have any secret agendas. Or they check their room for bugs. Or they post a watch at night to make sure they aren’t ambushed while they’re asleep. None of that necessarily means that they — as either players or characters — want to betrayed, bugged, or battled.

EXPLICIT FLAGS

None of which is to say, of course, that it wouldn’t be useful to know if the players want a confrontation with their abusive father or more challenges of a specific type.

But if you want to empower the players to signal that they want something included, it’s usually better to include specific mechanism for them to directly signal that, rather than trying to intuit signal from proximate cause.

In character creation, for example, you can have players make a specific wants list for the campaign.

The stars and wishes technique (created by The Gauntlet) can provide a simple structure for feedback at the end of sessions: Each player awards a star (indicating something they really liked about the session) and makes a wish (for something they’d like to see happen in a future session).

Along similar lines, I’ve used a technique I call gold starring, in which each player gets a “gold star” that they can at any time “stick” to an element of the campaign (even an element that hasn’t been established yet) to signal its importance to them. (They can also move their gold stars at any time.)

For stuff like, “I think it would be cool if there was a secret door here!”, storytelling games are designed entirely around narrative control mechanics and it’s not unusual to see similar narrative control mechanics lightly spicing roleplaying games, too.

The common denominator in all of these techniques, of course, is that you’re explicitly asking the players for specific information and, in response, the players are clearly signaling what they want. The resulting clarity means you can have confidence and focus in how you respond to your players’ semaphoring.

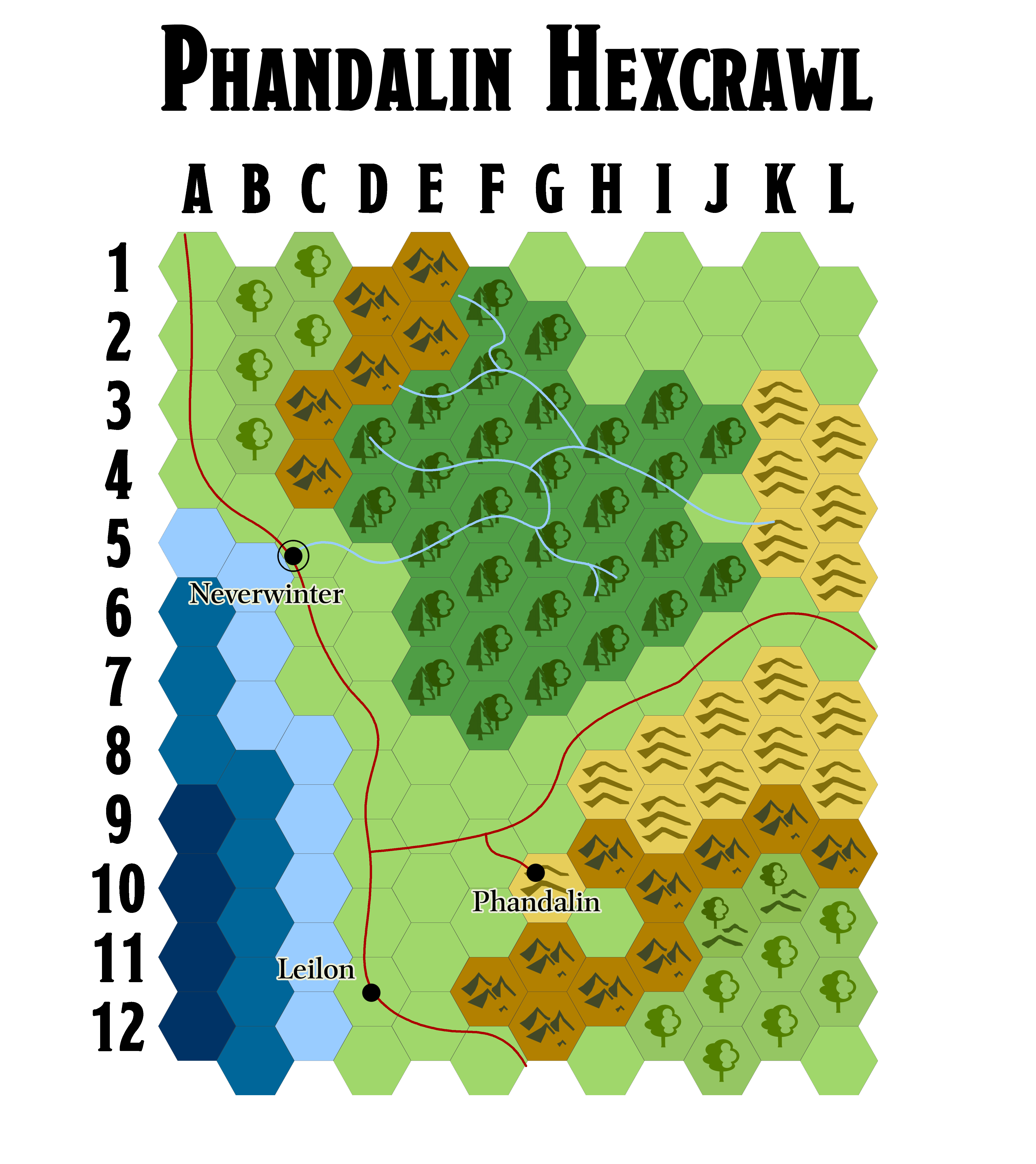

Phandalin Hexmap

Phandalin and the surrounding region of the Sword Coast have featured in three D&D adventures:

Here I’ve adapted Mike Schley’s excellent region map, featured in each of these adventures, into an accurate-but-simplified hexmap.

The reason for creating a map like this, of course, is to serve as a GM’s map while running a hexcrawl:

- The alphanumeric hex grid makes it easy to key content to the map.

- The simplified iconography makes it easier to adjudicate terrain modifiers.

For links to the original region map (including resources for creating a version you can use as a handout for your players), check the link below.

OTHER READING

Phandalin Region Map – Label Layers

DaveCon!

APRIL 26-28, 2024

Bloomington, MN, USA

I’ll be attending DaveCon this weekend!

The convention celebrates “all the Daves who were there at the beginning,” including Dave Megarry (designer of the Dungeon board game), David Wesley (creator of Braunstein, the game that inspired Blackmoor), and, of course, Dave Arneson (creator of Blackmoor, co-creator of D&D, and the father of modern roleplaying games).

Friday, 11am — Random GM Tips

Sunday, 10am — Three Clue Rule

Sunday, 11am — Book Signing

Sunday, 12pm — Opening Your Game Table

I hope to have the chance to meet many of you there!

If you can’t make it to DaveCon this month, my upcoming appearance schedule includes:

Green Dragon Fest — Knoxville, TN — May 16-19, 2024

GM Academy @ Tower Games — Minneapolis, MN — May 25, 2024

Philadelphia Area Gaming Expo — Oaks, PA — January 16-19, 2025

See you soon!

UPDATE: Due to a scheduling conflict, Random GM Tips will be at 11am on Friday instead of 12pm!

Ptolus: Running the Campaign – No, But…

DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 37B: An Uneasy City

At the gates of the Necropolis, Tee stopped and spoke with the Keepers of the Veil. She inquired after records of those buried in the Necropolis, hoping that they might indicate the location of Alchestrin’s ancient tomb. The knights didn’t keep records of that sort, but they suggested that one might inquire at the Administration Building in Oldtown.

At the end of Session 36, the PCs realized that what they thought was Alchestrin’s Tomb was actually a false tomb that had been constructed from scavenged sarsen stones that bore Alchestrin’s sigil.

This left them stymied. (Which was surprising to me: I once again thought it would be obvious that the stones must have been scavenged from somewhere nearby – particularly since they had been told Alchestrin’s Tomb was in this area – and therefore all they needed to do was look around the area a little more to locate the actual tomb. But they didn’t think to do that.)

They did, as you can see here, have the idea of asking the Keepers of the Veil – an order of knights who guard the borders of the Necropolis – to see if they would have a record of the tomb.

That makes logical sense, but in this case I knew from my notes that the Keepers didn’t have those records. (I did make a Knowledge check to see if one of the knights they spoke with would just coincidentally know the location of Alchestrin’s Tomb due to their experience with the Necropolis, but they failed the check.)

So at this point we have a fairly straightforward execution of the Spectrum of GM Fiat: I could just say, “No, the Keepers don’t have those records.” But you generally want to avoid simply saying “No” if at at all possible, which means that this is a perfect opportunity for a No, but…

In fact, it’s the perfect opportunity for a diegetic No, but… I know the Keepers don’t have those records, but that such records can be found in the Administration Building. I could just tell the players that (e.g., “Elestra, you’d know that such records would typically be kept in the Administration Building”), but in this case there’s no reason that the Keepers can’t know that. (It actually makes perfect sense: Although they don’t keep these records, it’s easy to imagine why those keeping watch over the undead and other dangers of the Necropolis would need to access them and, therefore, know where to find them.) So I can simply put the No, but… into the mouths of the Keeeprs and make it a natural part of the game world and the flow of play.

Ranthir spent the morning hours at the Administration Building, seeking records of Alchestrin’s Tomb.

Unfortunately, most of that time was wasted as Ranthir was shuffled fruitlessly from one ministry to another. He eventually found his way to the Ministry of Public Works and a relatively friendly older woman who showed him to what she thought “might be the proper room”. It was stacked high with moldering stacks of yellowing, unorganized parchment. In some ways, it was Ranthir’s perfect heaven… but it still left him stymied in his search for the Tomb.

Shortly thereafter, Tee caught up with him, assessed the situation, and made a quick circuit. Leaving a few greased palms in her wake, Tee was able to secure him assistance in sorting through the papers. This sped his task somewhat, but despite the help he was no closer to finding the Tomb by the time he had to leave.

When Ranthir actually goes to the Administration Building later in the session and tries to look up the records, however, I swapped off the Spectrum of GM Fiat and turned things over to the good ol’ fictional cleromancy of the mechanics…

… and Ranthir promptly failed his skill check.

(Tee showed up later and tried to help, but after some more bad rolling, it was still a failure.)

So here we go from No, but… to No.

Of course, some might ask why I had Ranthir roll for this vital information in the first place! If you roll for getting clues like this, then you risk the roll being a failure and the PCs not getting the clue! And, in fact, this horrible disaster is exactly what has happened!

I certainly could have stayed on the Spectrum of GM Fiat and ruled that Ranthir, having gotten to the right place, would automatically find the information he was looking for. But in this case, it’s not what my notes said, so that outcome really would have been a fudge. (Don’t fudge!) More importantly, though, I don’t actually care that Ranthir missed this check. It’s not my problem. It’s the players’ problem!

Because I know that:

- the PCs don’t actually NEED to get into Alchestrin’s Tomb in order to continue making progress in the Banewarrens (so it’s not a load-bearing aspect of the scenario);

- there’s other ways for them to find Alchestrin’s Tomb (remember the Three Clue Rule); and

- there’s lots of other leads the PCs can pursue (so the campaign isn’t going to stall here).

And so this is yet another situation where I can just be okay with failure being meaningful and seeing where it will take the campaign.

Campaign Journal: Session 37C – Running the Campaign: Patron Exhaustion

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

Archives

Recent Posts

- Ex-RPGNet Review: Big Eyes, Small Mouth – GM Screen

- The Vladaam Affair – Part 13B: Magi Guildhouse – 1st Floor

- Advanced Gamemastery: Adversary Rosters

- The Vladaam Affair – Part 13: Red Company of Magi

- 5E Monster: Pearl Golem

Recent Comments

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: City State of the Invincible Overlord

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: City State of the Invincible Overlord

- on In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 23A: Let Slip the Dogs of Hell

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: Big Eyes, Small Mouth – GM Screen

- on Empower Your Prep: The Rachov Principle

- on 5E Monster: Pearl Golem

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: City State of the Invincible Overlord

- on 5E Monster: Pearl Golem

- on Xandering the Dungeon – Addendum: How to Use a Melan Diagram

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: Big Eyes, Small Mouth – Fast Play Rules