The Three Clue Rule states:

For any conclusion you want the PCs to make, include at least three clues.

The underlying theory behind the rule is that having three distinct options provides sufficient redundancy to create a robust scenario: Even if the PCs miss the first clue and misinterpret the second, the third clue provides a final safety net to keep the scenario on track.

This logic, however, also leads us to the inversion of the Three Clue Rule:

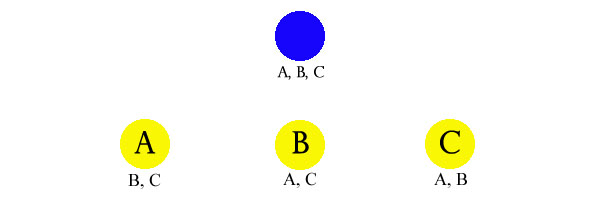

If the PCs have access to ANY three clues, they will reach at least ONE conclusion.

In other words, if you need the PCs to reach three conclusions (A, B, and C) and the PCs have access to three clues (each of which would theoretically allow them to reach one of those conclusions) then it is very likely that they will, in fact, reach at least one of those conclusions.

And understanding this inversion of the Three Clue Rule allows us to embrace the full flexibility of node-based design. Here’s a simple example:

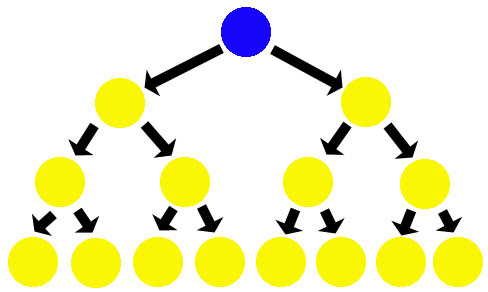

The scenario starts in the blue node, which contains three clues – one pointing to node A, one to node B, and one to node C. Following the inverse of the Three Clue Rule, we therefore know that the PCs will be able to conclude that they need to go to at least one of these nodes.

Let’s assume they go to node A. Node A contains two additional clues – one pointing to node B and the other pointing to node C.

At this point the PCs have had access to 5 different clues. One of these has successfully led them to node A and can now be discarded. But this leaves them with four clues (two pointing to node B and two pointing to node C), and the inverse of the Three Clue Rule once again shows us that they have more than enough information to proceed on.

Let’s assume they now go to node C. Here they find clues to nodes A and B. They now have access to a total of seven clues. Four of these clues now point to nodes they have already visited, but that still leaves them with three clues pointing to node B. The Three Clue Rule itself shows that they now have access to enough information to finish the scenario.

(Note that we’re only talking about clue access here. That doesn’t mean that they’re guaranteed to find or correctly interpret every single clue. In fact, we’re assuming that they don’t.)

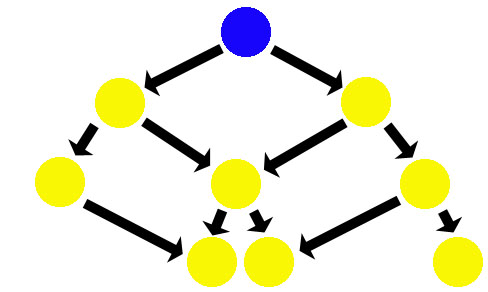

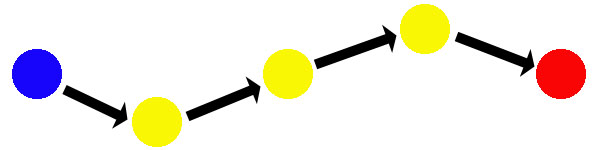

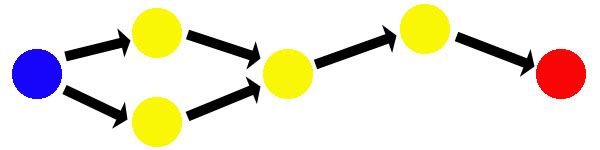

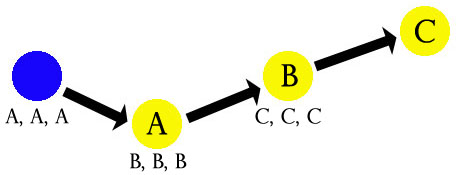

Now, compare this node-based design to a comparable plotted approach:

Note that the plotted approach can also be broken down into distinct nodes. And in terms of preparation, the plotted approach requires the exact same resources: Four nodes and nine clues. But the non-plotted design is richer, more flexible, and leaves the PCs in the driver’s seat. In other words, even in the simplest examples, node-based design allows you to get more mileage out of the same amount of work.

Of course, this entire discussion has been rather dry and technical. So let’s put some flesh on these bones.