Organization of campaign material is always an interesting topic for me, and I don’t think there’s enough discussion of actual, practical methods. (As opposed to the idealized theoretical stuff you usually see published in advice books.) Although I’m constantly learning new tips and techniques, I’ve also found that no two campaigns ever use the same methods of documentation: Even similar scenarios will often have unique characteristics that benefit from a different approach.

In the case of my Thracian Hexcrawl, I maintain four “documents”:

(1) THE HEX MAP: This is 16 hexes by 16 hexes, for a total of 256 hexes. (If I had to do it again I would either go with a 10 x 10 or 12 x 12 map: Coming up with 256 unique key entries was a lot of work. But I had some unique legacy issues from the pre-hexcrawl days of the campaign that resulted in a larger map.)

(2) THE BINDER: This contains the campaign key. It includes 2 pages of background information (current civilizations, chaos factions, and historical epochs), 8 pages of random encounter tables (one for each of the six different regions on the map), and a 100 page hex key.

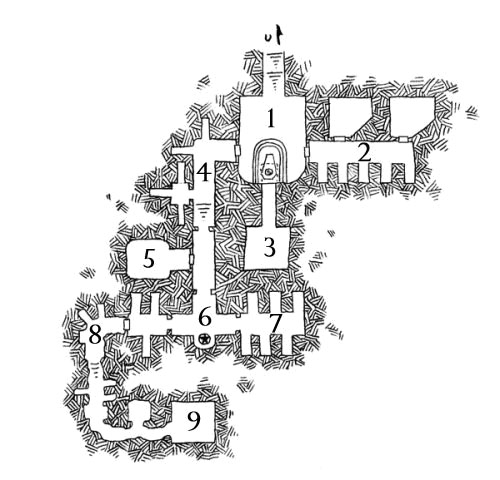

(3) THE FOLDER: Each document in this folder details a single location. These are locations with a key that takes up more than a single page and/or any location which requires a status update (because the PCs have visited it and shifted the status quo).

(4) CAMPAIGN STATUS SHEET: This document is updated and reprinted for each session. It’s responsible for keeping the campaign in motion. At the moment, the Thracian Hexcrawl campaign status sheet includes: A list of current events in Caerdheim and Maernath (the two cities serving as home base for the PCs); a list of empty complexes (which I reference when I make a once per session check to see if they’ve been reinhabited); the current rumor table; details about the various businesses being run by PCs; and the master loyalty/morale table for PC hirelings.

Of these documents, the most difficult to prep is, of course, the hex key itself (along with the folder of detailed locations). I spent two weeks of hard work cranking out all of those locations. But the up-side of that front-loaded prep is that, once it’s done, a hexcrawl campaign based around wilderness exploration becomes incredibly prep-light: I spend no more than 10-15 minutes getting ready for each session because all I’m really doing is jotting down a few notes to keep my documentation up to date with what happened in the last session.

DESIGNING FROM THE STATUS QUO

My general method of prep — particularly for a hexcrawl — is to originate everything in a state of “status quo” until the PCs touch it. Once the PCs start touching stuff, of course, the ripples can start spreading very fast and very far. However, in the absence of continued PC interaction things in the campaign world will generally trend back towards a status quo again. (This is something I also discussed in Don’t Prep Plots: Prepping Scenario Timelines.)

This status quo method generally only works if you have robust, default structures for delivering scenario hooks. In the case of the hexcrawl, of course, I do: Both the rumor tables and the hexcrawl structure itself will drive PCs towards scenarios.

The advantage of the status quo method is that it minimizes the amount of work you have to do as a GM. (Keeping 256 hexes up in the air and active at all times would require a ridiculous amount of effort.) It also minimizes the amount of prep work which is wasted. (If you’re constantly generating background events that the PCs are unaware of and not interacting with, that’s all wasted effort.)

It’s important to understand, though, that “status quo” doesn’t mean “boring”. It also doesn’t mean that literally nothing is happening at a given location. For example, the status quo for a camp of goblin slavers isn’t “the goblins all sit around”. The status quo is that there’s a steady flow of slaves passing through the camp and being sold.