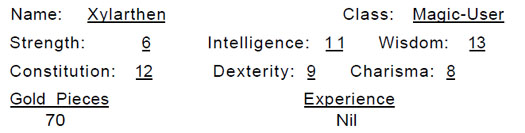

On page 10 of Men & Magic we get the first RPG stat block ever published. “A sample of the record of a character appears like this:”

This is also the closest thing we get to a character sheet in the OD&D rules. (Like many things in OD&D, you have to reverse engineer the general principle out of the example.)

I think the simplicity exemplified by this character sheet is something that a lot of gamers (including myself) look back on fondly: Roll your stats. Pick a class. And you’re ready to go.

Of course, like many things tinged with nostalgia and viewed through rose-colored glasses, this idyllic simplicity never actually existed. Xylarthen’s player still needs to select a race (since he’s an M-U he must be either a human or an elf), equipment (budget those 70 gp wisely), and his spells (well, a spell). And then he still needs to roll or calculate hit points, AC, encumbrance, and speed.

This division between between perception and reality actually proved quite vexing during the early design work for Legends & Labyrinths. I kept trying to get the game to the point where it was literally “(1) Roll ability scores; (2) pick race; (3) pick class”. And, of course, I kept failing. It wasn’t until I took a step back and re-analyzed what I was really trying to accomplish that I was able to get a satisfactory result.

But I digress.

The other interesting thing about Xylarthen is the description of his hypothetical creation: “This supposed player would have progressed faster as a Cleric, but because of a personal preference for magic opted for that class.”

I’m fairly certain that this makes OD&D the only edition of the game to put the idea that not all characters need to perfectly optimized front-and-center. But I also find the passage interesting because it highlights one of the features of rolling your ability scores in order: You are given the raw core for a character. What you choose to do with that core is up to you.

When was the last time you saw a wizard who didn’t have their highest ability score in Intelligence?

The insistence that the game can only be “fun” if your character is perfectly optimized limits the scope of the game. It takes character concepts off the table.

Of course, there are plenty of people who would argue that the guy playing Xylarthen is destined to have “less fun” than if he’d played a cleric. (Or was playing in a game where he could tweak his stats so that Xylarthen looks like every other magic-user in the game.)

And I get that. I can also appreciate that it can be annoying to come to the session saying, “I want to play a magic-user.” And then rolling an Intelligence of 6 and making the character you want to play completely untenable.

And this does, in fact, become less tenable because of the expected longevity of most characters in modern RPG’s. When a character has an expected lifespan of a couple of sessions (if he’s lucky), you can be a bit more philosophical about tackling an unexpected challenge than when you’re expecting to be playing this guy for the next year and a half.

But, on the other hand, Xylarthen sure looks like fun.

The counter-argument, of course, is that nothing stops me from making a wizard with his highest abiltiy score in Wisdom. True. But there is a distinct difference between facing a challenge and dealing with a self-imposed handicap. Just as there is a difference between being given a character and seeing what you can make of it and carefully scultping every detail of the character for yourself.

And I think there’s also a tendency to read the word “challenge” and think that I’m merely talking about the gamist side of the game. But I’m also talking about a creative challenge. The act of creation does not always have to begin with a blank slate. In some cases, deliberately eschewing the blank slate will give unexpected and extraordinary results which might never have been achieved if you limit yourself to a tabula rasa.

The Holmes Basic Set has an interesting section on “Hopeless Characters”:

Sometimes the universe of chance allows a character to appear who is below average in everything. At the Dungeon Master’s discretion, such a character might be declared unsuitable for dangerous adventures and left at home. Another character would then be rolled to take his place.

The act of rolling up a set of ability scores is literally perceived as the moment of creation. When you reject a stat block you aren’t rejecting numbers which aren’t appropriate for your character, you’re rejecting a character who is unsuitable for your play.

The shift in perspective is subtle, but notable.

And this, again, gets back to the idea that character creation itself is a part of the gameplay — not merely a means to an end, but an important part of the process itself. Character creation is not being seen as a prelude activity in which you craft the character you will be playing. Rather, from the moment you pick up 3d6 to roll up their Strength, the game has begun: The ability scores give you the character you will play. And then, from that point forward, it’s your decisions that shape that character’s destiny.

Necropost! There are rules for rolling in order in 3e, it’s called organic character creation and is kind of nestled at the start of the chapter (I forget which one). I found a lot of players recoiled from this idea as it gave them less choice (which is my biggest gripe with 4e), so I came up with a kind of blend where they rolled 2d6 for each of their scores resulting in 2-12 for each one, then they rolled 2d6 six times, discarding the lowest. They could then assign these scores to any of their six attributes. I explained that the organic section is what they were born with, whereas the extra d6 was how much they learned in their lifetime before they became an adventurer. This met with much more success and felt better to me because my players were still getting the all-important chance to choose who their character is without just playing a stat block.

A thought has occurred to me, that “class” is an odd word to use for a character’s talents and skill specializations. More normal words to choose might have been “role” or “occupation” or “specialty” or even just “job”. Prior to D&D, “class” I think was only really used to describe people in the sense of *social class*, or else a group of students. (I checked the OED.) The sense of “class” as a general categorization would have been a more technical mathematics or biology thing, or else it was used when you were categorizing sailing vessels.

@colin: Comes from wargames. In many wargames, units would belong to different classes, with each class have its own features/rules. Gygax, in particular, used the term frequently in his wargames (such as Alexander the Great).

Reading some exchanges between Gygax and Arneson, you can see that Gygax used the word “class” to refer to levels: “There are nine classes of fighting-man.” This was because, in the early drafts of D&D, levels were not initially numbered—only named.

@Justin, So it’s either a wargaming idiosyncrasy or a Gygaxian one? Because the actual army doesn’t use the word “class” like this. The navy kind of does, but only for warships, not people.

@Kaique, kind of weird to think about, that we might have had characters gaining class and “classing up”, instead of leveling.

@Kaique: Yup. Same concept: A character gaining experience was being conceptually modeled as becoming a more elite class of unit.

Once you understand this paradigm, it can help you understand some passages in the original 1974 rulebooks that otherwise seem confused or clumsy. (For example, whenever they talk about a monster “fighting as a Veteran” or the like, that would have been a pretty bog standard procedure for a wargamer thinking about how individual units should be handled in the rules.)

@colin: I wouldn’t really describe it as an idiosyncasy, any more than referring to students as belonging to a “class” is an idiosyncrasy. Wargames had a specific need and they coined a term for it, using an English word with a meaning that already covered their need.