The awesome thing about failure in roleplaying games is that it provokes creativity, heightens the stakes, and drives the adventure in interesting directions.

I would even go so far as to say that an adventure without meaningful failure is, all other things being equal, inherently worse than one with it.

Unfortunately, this may not be immediately obvious if you’re used to scenarios prepped as plots (i.e., a predetermined sequence of events). In a scenario prepped as a plot – particularly if the GM is using railroading to enforce that plot – there is only one path. And if there is only one path, any failure must be interpreted as temporary and, therefore, meaningless.

Failure is meaningful (and interesting) when it creates an obstacle or consequences, and therefore requires the creation of a new path.

Once again, if you’re used to prepping and running plots, this can sound incredibly daunting: With a plot you have to figure out how to reliably route the PCs from Scene A to Scene B. That’s non-trivial and if the pre-planned routing fails, improvising an alternate route on-the-fly is tough.

But if you’re prepping situations instead of plots, then the pre-planned route doesn’t exist. And if the pre-planned route doesn’t exist (or isn’t important), then it’s not even your job as the GM to come up with the alternate route! It’s the players’ job.

Despite this, though, you may find that failure is still just causing the wheels of the game to spin. Why?

Well, another common way in which failure can become meaningless is when unnecessary action checks are being resolved. As described in The Art of Rulings, action checks should generally only be made when failure is either interesting, meaningful, or both.

If you’re a beginning GM trying to figure out how to make failure meaningful, here’s a couple of simple techniques that you should be able to rely on.

INTRO TECHNIQUE #1: NO RETRIES

The easiest way to implement meaningful failure is to simply not allow retries: If you failed to pick the lock on the door, that failed check tells us that you’ll never be able to pick that lock. You did your best; it didn’t work.

Now what?

Kick it in? Cast a spell? Look for a different entrance? Look for a key? Seduce the housekeeper? I dunno. You tell me.

But as you can see from these example alternatives, each of these new paths creates interest: The PCs are leaving evidence or engaging in further exploration or creating new relationships. Arguably all of these are, in fact, more interesting than if they had simply picked the lock and gone through the door.

Note: A trap that you can fall into here is thinking, “Well, if failure is better, then I should just force everything to be a failure!” There’s a longer discussion to be had on this point, but the short version is: Success is also important if, for no other reason, than that the players will become increasingly frustrated if they can never actually accomplish anything. So let the dice fall where they may.

To be clear, this technique is not the be-all or end-all of how to adjudicate failure. There are more advanced or gradated techniques that can be used to good effect with practice. But if you’re just getting started, you don’t have to make it complicated.

INTRO TECHNIQUE #2: QUICK-AND-DIRTY FAILING FORWARD

Okay, so you’ve done that for a few sessions and you’re starting to get a feel for what meaningful failure looks like in actual play, but you’re also starting to chafe a little bit under the straitjacket of never allowing retries.

You’re ready to make it a little complicated.

What we’re going to use here is a technique called failing forward: The mechanical result of failure (e.g., rolling below the target number) is described as being a success-with-complications in the game world.

A simple rule of thumb for when you should use failing forward is whenever disallowing a retry feels a little weird to you: Why can’t the PC just try to pick the lock again?

In our first technique, the intended path fails and the PCs need to find an alternative path. Failing forward is a different way of making failure meaningful because you don’t annihilate the intended route (whether you prepped it or the players chose it). You just complicate it.

Coming up with interesting complications on-the-fly, though, can feel intimidating. So, when in doubt, just impose a cost: You succeed, but…

- You have to pay extra.

- You took damage.

- Your equipment broke.

- It took extra time (if that’s relevant).

- Someone knows you did it who you didn’t want to know.

If you have a better idea, great. But if not, these five broad categories can cover like 90% of fail forward checks. In fact, you’ll usually have multiple options. When picking a lock, for example:

- You open the door, but trigger the security trap. (You take damage.)

- You open the door, but your lockpick snapped off in the lock. (Your equipment broke.)

- You open the door, but it took twenty minutes and now you only have ten minutes before the Count returns home. (It took extra time and it was relevant.)

If nothing works and you can’t think of something outside the box, that’s fine: Either don’t make the check in the first place (just let them automatically succeed) or default back to no-retries-allowed and move forward.

Advanced Tip: You can get a little fancy here with a fortune in the middle technique by offering the cost to the player. For example, “You’ve almost got the lock open, but the hacked security camera is going to come back online. Do you stay and open the door or GTFO before the camera spots you?”

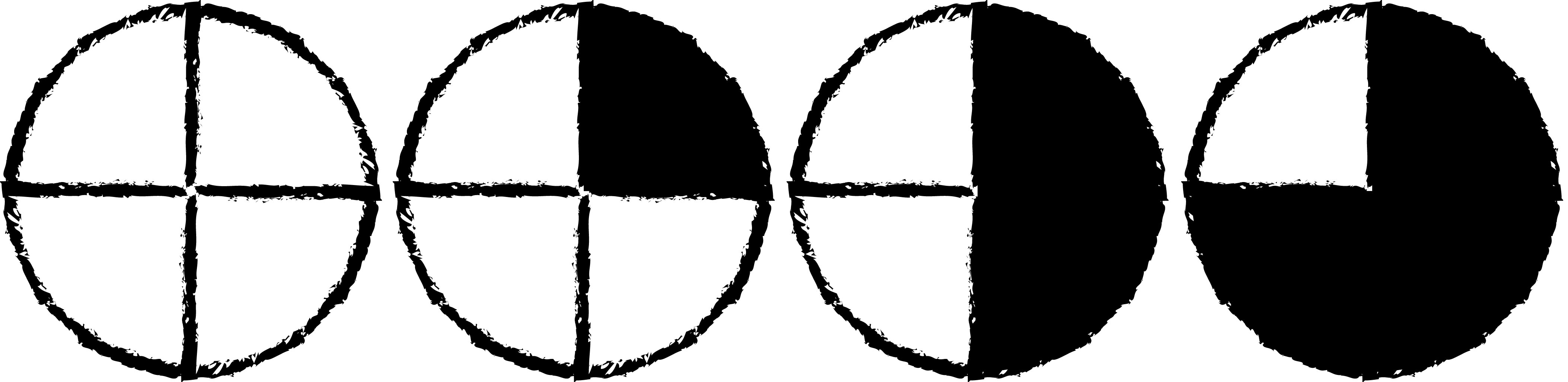

INTRO TECHNIQUE #3: BASIC PROGRESS CLOCK

A progress clock is a simple, visual way of tracking how close a particular outcome is to happening. There are a lot of different ways that you can use a progress clock, but for today, when the PCs fail their first check during an endeavor (e.g., sneaking into mansion, tracking a band of orcs, investigating a cult’s activities in Dweredell):

- Create a progress clock by drawing a circle and dividing it into four, six, or eight parts.

- Set a significant consequence or overall fail condition. (For example, security at the mansion realizes there are intruders and the alarm is raised, the PCs lose the trail of the orcs and can no longer follow them, or the cultists succeed in summoning a demon who begins rampaging though the Great Market).)

- Whenever the PCs fail a relevant check, fill in one part of the progress clock.

- When the progress clock is filled, trigger the consequence or fail condition.

This technique can be used with any type of action check, but for our purposes primarily provides a default consequence for failing forward: If you can’t think of any other consequences, just fill in the next section of the progress clock and explain the connection.

Progress clocks can exist in one of three states at that table:

- Open Clock: When you create the clock or fill in a section, you show it to the players. This is often the easiest method, making it crystal clear what the consequences of a failed check are with no fuss.

- Hidden Progress: When you create a clock, you directly or indirectly tell the players that it exists. (For example, when they’re sneaking into a mansion you can clearly state that there’s a risk the security team will detect them.) But the clock itself remains hidden. The players don’t know how large the clock is or exactly what the progress on the clock is. However, because the clock’s progress is hidden from them, you will need to clearly communicate the consequences of failure to them. (For example, if they fail forward on a lockpicking check, you might describe how they managed to get the door open, but they’ve left clear signs of tampering that might be noticed. Such explanations, you’ll note, will also inform exactly how the failure condition plays out – in this case, it’s possible that the alarm is sounded because someone noticed the damaged lock.)

- Secret Clock: You create the clock without telling the players it exists; it serves strictly as a tool for you to keep track of things. As with a hidden progress clock, it’s your responsibility to continue clearly communicating the consequences of failure to the players in your description of the game world.

Advanced Tip #1: Other events or actions can fill in sections of the progress clock even if there isn’t a failed check. If something happens that logically moves events closer to the progress clock’s outcome, fill in a section. (Similarly, particularly terrible failures might fill in more than one section at a time.)

Advanced Tip #2: It’s also possible for progress clocks to “run backwards.” If the PCs do something that sets back the plans of the cult, for example, it may make sense to erase one of the filled sections of the progress clocks. (On a similar note, progress clocks are not inevitable: If the PCs break into the mansion and get out before filling the progress clock, the alarm doesn’t sound. If they wipe out the cult, the demon is never summoned. And so forth.)

FURTHER READING

Prep Tips for the Beginning DM

Prep Tips for the Beginning GM: Cyberpunk

Pacing for the Beginning GM

Roleplaying for the Beginning GM

This… this is a really good article. This is like, ten years’ worth of GM advice condensed down into a 5 minute read. It would take a long time for a beginning GM to outgrow the advice in this article.

A simple but very helpful article. Could very much have done with reading something like this when running my first 5e campaign – more useful than the entirety of the DMG.

Technique 2 is why I find the 10-minute ‘dungeon’ (or general dangerous exploration) turn so useful – without having to think much about it you immediately have the consequence of time passing, and with it passing there’s the risk of more rolls to see if there’s an encounter.

In one sense, the roll-for-encounter-every-20-minutes procedure is a mini clock of two segments, with the conclusion of the clock being a 1-in-6 chance of coming across something which might sap resources. The regular procedure does a lot of the heavy mental lifting for the GM.

Outstanding article. @Bobamk is right—there’s a ton of good judgement packed into succinct advice, here.

I would like to add that many game systems are much too prescriptive and mechanical in this regard. They spend a ton of effort on fine-grained adjustments to the probability of success, and very little on how to handle the role-playing implications of success or failure.

The rule I use is that any adjustment to probability the player and GM use, should be one that the character would notice readily. So, if you pick up a magic bow and you can shoot twice as far and still hit the usual target, that’s great. If you pick up a bow and it takes an hour of shooting with careful record-keeping to observe a 5% difference, that’s not. Role-playing should not be an exercise in pitting one spreadsheet versus another spreadsheet.

—Well, wizard, have you finished my Longbow of Might?

—Yes, your majesty. Here it is, with a dozen fine arrows to match.

The King looses twelve shots at the butts, and hits exactly as often as usual.

—What cozenage is this, you ’prentice spell-monger? You promised me magical accuracy!

—Your Majesty, at this range you ordinarily hit in the gold just one shot in ten. My enchanted longbow improves your probability of success by five parts per centum, meaning that…

—Methought we spoke of archery, not cyphering. I have a Chancellor of the Exchequer already.

—Your Majesty misunderstands, I meant

—WHAT?

—I beg your pardon, I meant that I failed to explain clearly. The enchantment improves your majesty’s likelihood of success. In any given series of shots, there might or might not be any difference in the number of successes. The statistical formula is…

—Hold. There might not be any difference? So your magical bow only works some of the time?

—No, sire, it works all of the time, but only some of the time is there any practical difference in the outcome.

—How can it work and not make a difference? If it doesn’t make a difference, it’s not working. Do you take me for a fool?

—By no means, your majesty. It’s merely that the laws of probability are not, um, easily accessible to, ah, those not educated in

—Bailiff! Throw this imposter into the nearest oubliette.

I agree with the above commenter…this is an excellent post in that it captures concisely some great techniques. I particularly like the concept of a Basic Progress Clock. This is something I’ve employed somewhat intuitively in my games, but I’ve never really thought about it as an articulated technique. I have two players in my current game that are just starting out as new GMs in other games, so I’ll have to direct them to this post for some great tips. Peace.

When revealing an open basic progress clock as the result of a failure, does the clock start with a segment filled in for that initial failure, or does it start blank?

Super useful article. I think I have defaulted to the “Hidden Clock” option without telling players that there IS a clock. Making clear to the players that there is a failure condition that I’m tracking progress toward is something I’ll definitely consider, to raise the stakes.

The Progress Clock section makes me think of Pathfinder 2nd Edition’s “Victory Point” system, which uses the +10/-10 critical success/fumble mechanism, to have four different results toward progressing toward a positive condition. It, of course, can be reversed to (or complemented with) a negative terminal condition as well. Here’s their system: https://2e.aonprd.com/Rules.aspx?ID=1189

One note on Failing Forward: As a player, I’ve found failing forward to be incredibly frustrating in practice. Having my lockpicks break (for example) as a result of a failed check feels like a much more punishing result than simply failing to pick the lock. It feels both more punishing and deeply unfair (and unfun) if the GM is making up the result on the spot and it wasn’t clear to me ahead of time how much I risked this outcome.

An expert GM can come up with fail forward results that are both a reasonable level of punishment and feel fair, but for a novice GM I’ve seen this is extremely difficult. I think this is pretty straightforwardly fixed by having fail forwards always phrased as an offer. Examples: “The last pin seems sticky. You can force the door open, but your lockpicks will break off in the lock if you do.” or “The door resists your usual techniques. You can do something experimental, but if there’s a trap you’ll definitely trigger it.”

D&D at least has a built in fail forward for time: You can “take 20” if you have enough time, and I’ve usually ruled that in the absence of other penalties you get one shot to do it fast, and then can take 20 with your second try but can’t use a standard roll for the second try. This also fits well with the “let the player choose” mentality for failing forward.

@David, you can create an open progress clock before the PCs have failed anything. “Okay, you’re trying to sneak through the snake temple. Here’s a clock for how much disturbance you’ve caused.” “When that’s full, the whole temple will be roused and start hunting you. Don’t screw up, ok?”

It’s worth mentioning that clocks in this style derive from Apocalypse World, refined and developed by Blades in the Dark. There’s lots of advice on how to use them in Blades.

As a new GM these tips are great! Really like the idea of the PC offering system.

Great advice! Here’s a question though: no re-attempts allowed… ok, let’s have another character have a go, and then another one… is there a way to stop that rather annoying re-attempt through the whole party thing?

Your statement that failure is the enemy of a plotted adventure seemed paradoxical to me at first. After all, nearly all movies show the hero or heroes failing at least some of the time. If they didn’t, the movie would often be much shorter! Then it occurred to me that, in a railroaded adventure, the author/GM is the one who decides *how* and *where* the PCs will fail. For instance, the plot demands that the villain gets away. Or that that the PCs are captured. Or that they’re unable to cast speak with dead. And so forth.

One variation on progress clocks I’ve seen used if someone wants the amount of time remaining to be unpredictable is to use dice. For example, have an extra-large d8 in the middle of the table, and every time you’d “fill in a wedge”, instead roll the die. If it comes up 1 or 2, replace it with an extra-large d6. Repeat until you’d replace an extra-large d4, at which point failure occurs.

@Che, if the PCs are messing around in ways that seem unrealistic, take a moment and ask “why would this be unrealistic?” For instance, if the strongest character in the party has failed to lift the gate, then we have established that it’s too heavy for any one character. If someone else wants to try, then they have to explain what they’re doing that Sir Beefalot didn’t already try. And if they say something dumb, like “I lift with my knees?” then you ask “Really? You think Sir Beefalot is that incompetent? Dude kills dragons for fun. No, really, give me a good answer or go try something else.”

Sometimes it’s totally reasonable to say, “you tried to light the fire and it didn’t catch. Now all the kindling is burnt so you can’t try again.” Or perhaps failing means you’ve pissed off the gate guard and he’s going to say “I’m going to tell you the same thing I just told your obnoxious friend: get lost!”

Or sometimes the answer is that there’s no particular reason everyone can’t take their turn trying, except that that would waste a lot of time. So let them try, but make wandering monster checks while they’re doing it, or fill in wedges in the “running out of time” clock, or do whatever bad thing is likely to happen if the PCs are wasting time.

If there’s no reason why wasting time is bad, then do like @sashas said above: you get one try to do it fast, and if that fails you can take 20 to do it slow. And if taking 20 isn’t good enough, then you just can’t.

(Also consider if your adventure would be better if you had put in a reason why wasting time is bad.)

And, of course, sometimes there’s no reason at all why everyone shouldn’t try. So just save time and call for everyone to roll right at the beginning.

Great article! I’ll use the clock idea for more interesting stealthy bits in Technoir…

@Che Webster & @Sachas:

In Call of Cthulhu the situation you’re describing is dealt with by the Pushing the Roll mechanic. Player rolls, fails, and has a choice: live with it, or “push” harder to get what she wants. Typically this involves a reroll, and the understanding that if it goes wrong they’re going to have to pay a price, like breaking their tools. The reason they can’t try again a dozen times is that the situation has changed: they have no tools, or more guards, or the spell backfired. When it’s a second player attempting to do the same action, quite often that counts as a push at my table.

After using this for a while some of my players started bargaining for pushes by offering up the consequence for if (when!) it goes badly, which is great.

I use clocks a lot. I often have three clocks in progress at different scales.

In D&D its usually 1 clock for the quest they are on, say to rescue a prisoner before they are executed, or to get the treasure before its buried in the deep vault. The failures are delays, ramping up the tension. The players can usually take risks that pay off by getting them closer, faster.

The second clock is normally a region clock where something offers to become serious complication if they don’t navigate the region efficiently. With this I have degrees of success such as : total failure = a battle with a large orc patrol that has been hunting for your group, moderate failure = you leave the woods but hear the cry of a large group of orcs that are pursuing now, mild failure = you leave the woods but you hear orc horns. Something has stirred them up.

The third clock can be in encounters: The guard is edging toward the gong, if he runs he could make it. You are trying to persuade her not to go for it. If you can slow them down and keep their eye on you maybe she wont notice the scout working around behind her. You have 3 rounds, each fail she is a bit closer to the gong and perhaps a bit more confident that even if you leap at her she will make it.

A variation on the clock is something I think of as a “best 2 out of 3” challenge — or 3 out of 5, or 4 out of 7. It sets both the number of failures that will bring the ultimate failure and the number of successes that will allow the players to complete the challenge. Works well for chase scenes. Combine it with the possibility of a “you succeed but . . .” outcome, as with the Apocalypse World mechanic, and you have a situation where the players can make progress while also incurring costs that make the next roll harder. Really amps up the tension.