I believe that dungeons should always be heavily xandered.

…

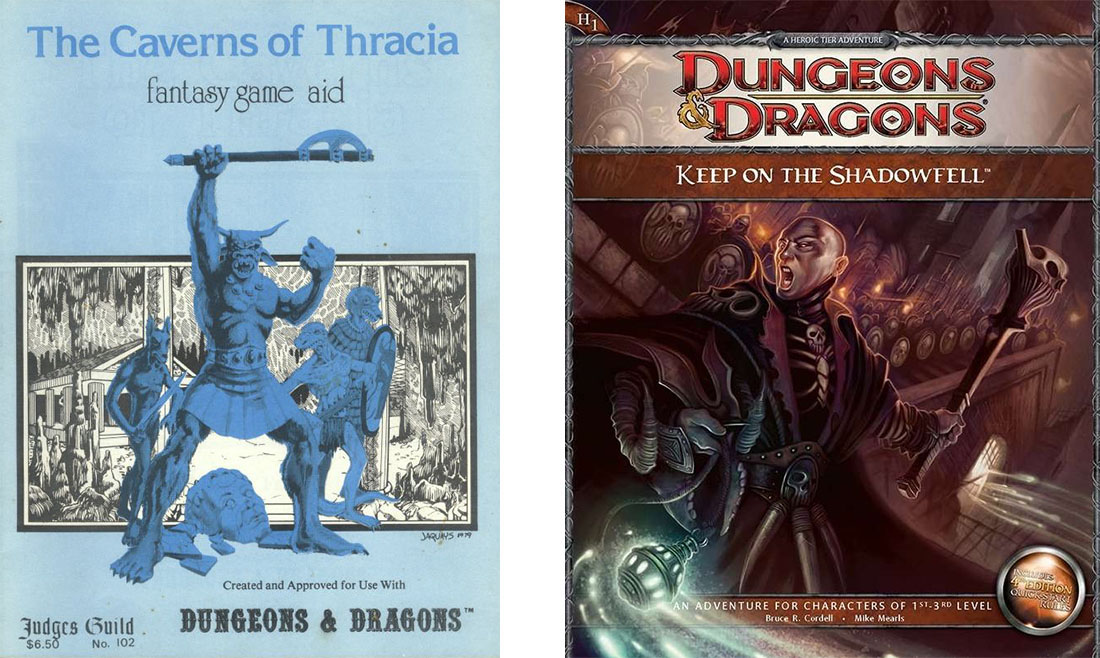

Okay, it’s true. I’m just making up words now. Recently, though, I’ve been doing some deep dives into the earliest days of D&D. I’ve been reading and running the rules and adventures of those bygone days and discovering — or rediscovering — the amazing work of Arneson, Gygax, and the many, many others who were exploring the brave new world of roleplaying games. When it comes to xandering the dungeon, what I wanted was a word that capture the pioneering dungeon design of Blackmoor, Greyhawk, and, above all, Jennell Jaquays, who designed Caverns of Thracia, Dark Tower, Griffin Mountain, and a half dozen other old school classics for Judges Guild, Chaosium, Flying Buffalo, and TSR. Because a word for that didn’t exist yet, I felt compelled to create one.

This article originally coined a different term. Click here for an explanation.

I first started running Jaquays’ Caverns of Thracia last year. It inspired an entire campaign, and while exploring its depths with my players over the past several months I’ve often found myself ruminating on the mysteries of its labyrinths and trying to unravel why it’s such an utterly compelling and unforgettable adventure. Along the way, I’ve come to the conclusion that everyone should be more familiar with Jaquays’ amazing work, so let’s take a moment to dive deeper into her legendary career and also consider what makes a dungeon adventure like Caverns of Thracia different from many modern dungeon adventures.

After amazing work in tabletop RPGs, Jaquays transitioned into video game design, and in that latter capacity she recently wrote some essays on maps she designed for Halo Wars:

Memorable game maps spring from a melding of design intent and fortunate accidents.

Jennell Jaquays – Crevice Design Notes

That’s timeless advice, and a design ethos which extends beyond the RTS levels she helped design for Halo Wars and reaches back to her earliest work at Judges Guild.

And what Jaquays particularly excelled at in those early Judges Guild modules was non-linear dungeon design.

For example, in Caverns of Thracia Jaquays includes three separate entrances to the first level of the dungeon. And from Level 1 of the dungeon you will find two conventional paths and no less than eight unconventional or secret paths leading down to the lower levels. (And Level 2 is where things start getting really interesting.)

The result is a fantastically complex and dynamic environment: You can literally run dozens of groups through this module and every one of them will have a fresh and unique experience.

But there’s more value here than just recycling an old module: That same dynamic flexibility which allows multiple groups to have unique experiences also allows each individual group to chart their own course. In other words, it’s not just random chance that’s resulting in different groups having different experiences: Each group is actively making the dungeon their own. They can retreat, circle around, rush ahead, go back over old ground, poke around, sneak through, interrogate the locals for secret routes… The possibilities are endless because the environment isn’t forcing them along a pre-designed path. And throughout it all, the players are experiencing the thrill of truly exploring the dungeon complex.

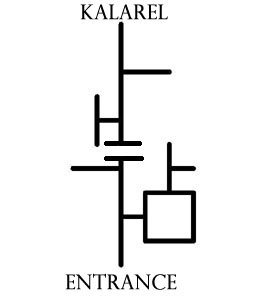

By way of comparison, Keep on the Shadowfell, the introductory adventure for D&D 4th Edition, is an extremely linear dungeon:

(This diagram uses a method laid out by Melan in this post at ENWorld. You can also find a detailed explanation in How to Use a Melan Diagram.)

Some would argue that this sort of linear design is “easier to run”. But I don’t think that’s actually true to any appreciable degree. In practice, the complexity of a xandered dungeon emerges from the same simple structures that make up a linear dungeon: The room the PCs are currently in has one or more exits. What are they going to do in this room? Which exit are they going to take?

In a linear dungeon, the pseudo-choices the PCs make will lead them along a pre-designed, railroad-like route. In a xandered dungeon, on the other hand, the choices the PCs make will have a meaningful impact on how the adventure plays out, but the actual running of the adventure isn’t more complex as a result.

On the other hand, the railroad-like quality of the linear dungeon is not its only flaw. It eliminates true exploration (for the same reason that Lewis and Clark were explorers; whereas when I head down I-94 I am merely a driver). It can significantly inhibit the players’ ability to make meaningful strategic choices. It is, frankly speaking, less interesting and less fun.

So I’m going to use the Keep on the Shadowfell to show you how easy it is to xander your dungeons by making just a few simple, easy tweaks.

XANDERING THE DUNGEON

Part 2: Xandering Techniques

Part 3: The Philosophy of Xandering

Part 4: Xandering the Keep on the Shadowfell

Part 5: Xandering for Fun and Profit

Addendum: Dungeon Level Connections

Addendum: Xandering on the Small Scale

Addendum: How to Use a Melan Diagram

Dark Tower: Level Connections