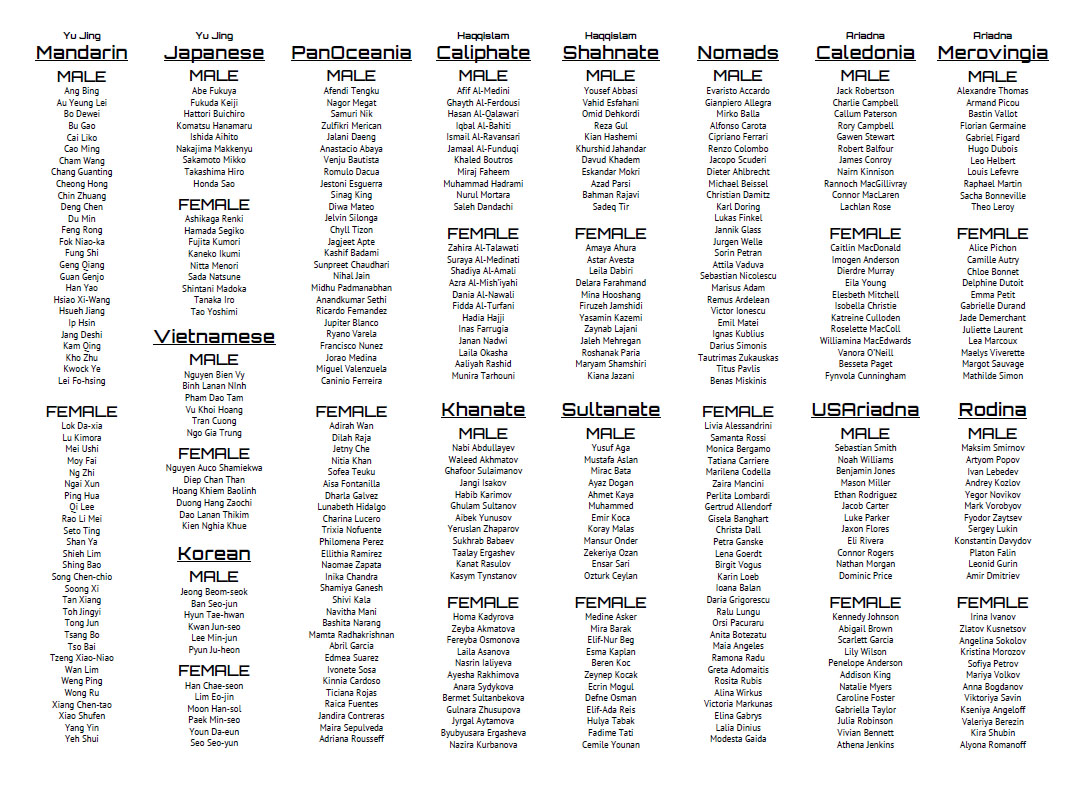

The Infinity universe is a glorious science fiction kitchen sink. A panoply of unique cultures and cool technology is all smashed together, and opportunities for adventure and excitement explode out of every interaction.

I’ve found that the incredible richness of this setting, however, can pose a unique challenge: When you’ve got Chinese and Korean and Arabic and Germanic and Scottish and Russian and Malaysian cultures all splayed out across a dozen alien worlds, it can create a real strain on even the most well-developed cultural literacy. And the leading edge of this challenge, at least for me, are the names: When the PCs seek contact with a new NPC and I’m put on the spot to create a name on the fly, that’s when the rubber hits the road. Years of practice with improvisation have given me a lot of confidence when it comes to Western European and/or flat-out fantasy names, but when a scenario calls on the distinction between Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cultures in the riven enclaves of Shentang, I just don’t have enough depth.

There’s only so many times the players run into Jing Li before it becomes a problem.

So I put a little elbow grease into it and created a tool that I think you might find helpful, too: A grand list of NPC names for Infinity.

GENERAL NOTES

Basic Use: Pick a name.

For Variety: Mix-and-match first and last names. (For example, take “Shing Bao” and “Tong Jun”. You can name a character “Shing Jun” instead.)

Disclaimer: Anywhere I’ve butchered local naming conventions, you can assume that it was a totally deliberate decision representing cultural drift over the next two hundred years. (Innocent whistling.)

ARIADNA NAMES

These have been split into four separate lists, one for each of the major cultures/political units on Dawn. All names are pulled from the appropriate cultural background.

- Rodina Gendered Surnames: The Western-style last names shown in the name list are gendered. Remove the –a suffix when using female last names for male characters (and vice versa).

NOMAD NAMES

Nomads are a chaotic mish-mash of disparate people. The list here includes Italian, German, Romanian, and Lithuanian names, mostly as a selection of names not found on other lists.

Nomad characters will also commonly pull from the USAriadna and Rodina (i.e., Russian) lists. Yu Jing and PanOceanian names are also not unusual. Mixing first and last names across multiple lists is encouraged.

PANOCEANIA NAMES

The PanOceanian name list is drawn from Brazil, Chile, the Philippines, Malaysia, and India.

Each name is culturally distinct (insofar as that distinction exists in the real world), but mixing-and-matching is consistent with PanOceania’s neo-melting pot (so don’t worry about crossing the streams).

PanOceanian characters could also use the Caledonian and USAriadnan lists (usually representing an Australian background).

YU JING NAMES

Mandarin, Korean, and Japanese names are Last-First. (Keep this in mind for characters who are related.)

Vietnamese names are Last-Middle-First. First and middle names can be freely interchanged when mixing and matching, however, so you’ve got a lot more options here than it might look like at first.

HAQQISLAM NAMES

Even in the real world, Islamic names are a pan-cultural mixture of local tradition, bureaucratic decree, and linguistic exchange. Haqqislam is an even more thoroughly mixed Islamic melting pot plus all the disruption entailed in a planetary exodus and colonization. In addition, the following notes are simplistic in the extreme. Basically: Feel free to mix-and-match with these names as much as any other.

Al Medinat Caliphate names are Arabic.

- Nasab: Arabic names often feature a sequence of patronymic names tracing an individual’s lineage; ibn meaning “son of” and bint meaning “daughter of”. (For example, Laila bint Miraj ibn Iqbal.) In the Human Sphere, it’s become more common to see matronymic bints rather than defaulting to the male line. (For example, Kinnia bint Jandira bint Adriana.)

- Surnames: Arabic surnames follow a dizzying array of cultural traditions. Historically, it wasn’t unusual for Arabs not to have any surname. (A practice which hiraeth culture brought back into fashion.) Honorific laqab are also possible, but beyond the scope of this cheat sheet. Nisbah surnames indicate where the individual comes from (or is associated with), and in some cases end up being an inherited surname instead. For this cheat sheet, roughly half of the Arabic surnames are nisbah for Bouraki locations. (You can kludge your own by looking at the map of Bourak and, generally, just adding “Al-“ at the beginning and an “i” at the end.)

Funduq Sultanate names are Turkish.

- Surnames: Used In a purely Western style (although often have an Arabic derivation, so stealing from the Arabic list can work well).

Gabqar Khanate names are Afghani and Kyrgyz. (Each listed name is culturally distinct.)

- In Gabqar, naming traditions have blurred, so you can freely mix-and-match the Afghani and Kyrgyz naming practices described below.

- Subordinate Names: Afghani MALE names often have two parts, with one usually a subordinate name. These subordinate names can appear first or second, but the other half is always the character’s “proper name” regardless of position. (You can create these by using the sample list of subordinate names or by mixing-and-matching from the list).

- Sample Subordinate Names: Mohammed, Abdul, Gholam, Ali, Khan, Jan, Shah, Din, or attaching the suffix –ullah to the other name (e.g., Kanatullah).

- Gendered Surnames: The Western-style last names shown in the name list are gendered. Remove the –a suffix when using female last names for male characters (and vice versa).

- Patronymic Surnames: Kyrgyz alternatively uses a more traditional patronymic surname. These are –kyzy (son of) and –uulu (daughter of) and can be constructed by combining them with any first name (e.g. “Ensar” becomes “Ensarkyzy”).

Iran Zhat al Amat Shahnate names are Persian/Iranian.

- Surnames: Although originally constructed similarly to Arabic nisbah, Persian names are inherited in a Western style.