In this seminar, Sandy Petersen — original designer of Call of Cthulhu and owner of Petersen Games (among many, many other accomplishments) — walks the audience through his process for writing a horror scenario. Along the way he offers a prodigious grab-bag of advice. I thought the material was fascinating enough that I took notes and broke his process down into a step-by-step model. I’m polishing those notes up and sharing them here because I think they’ve got a general utility.

THE BASICS ACCORDING TO M.R. JAMES

Petersen draws inspiration from three rules M.R. James set for his famous ghost stories (a body of literature which inspired, among many others, Lovecraft himself):

1. The ghost is malign.

The antagonist for your horror story doesn’t necessarily need to be a ghost. (And, in fact, M.R. James’ ghosts were quite varied in their properties.) But your antagonist shouldn’t be revealed as having good intentions.

2. Place your story somewhere the players can imagine themselves.

Petersen discusses that his original intention for Call of Cthulhu was to set it in the modern day: Lovecraft wasn’t writing historical fiction, after all. He was writing cutting edge thrillers. When he wrote “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1922, for example, a steamship was the biggest and most powerful thing that had ever been accomplished with human technology. So when he rams Cthulhu with the steamship, it’s not an historical oddity — it’s Lovecraft saying “the biggest thing we have can’t stop Cthulhu”. Petersen asserts that if Lovecraft had written the story in 1945, he would have nuked Cthulhu.

This is not to say you can’t set your scenario in other settings. It’s just that you have to work harder: You can do it in the ’20s, the 1890’s, the 15th century, or on a spaceship. But you have to make the players feel as if they could actually be there.

3. No jargon.

M.R. James was talking about avoiding the terminology of theosophists and the other pseudo-scientific approaches to the supernatural that were arising during his time. For Petersen, this means using fiction-first declarations instead of mechanics-first declarations. Horror doesn’t come from game mechanics.

THE SCENARIO SEED

1. Pick a scene from a movie, book, etc. (Example: Burning the rabbit from Velveteen Rabbit.)

My thought on this (and I suspect it’s probably true for Petersen outside of seminar contexts) is that it doesn’t need to be a scene you’ve literally plucked from an existing piece of literature. What you’re looking for is a strong, emotionally powerful image or event.

2. Pick a place. (Example: Hot springs.)

3. Pick an opponent. (Example: 500 year old undead ancestor.)

THE SCENARIO SPINE

A. Look for interesting combinations/connections in the elements of the scenario seed.

For example, the ancient undead is somehow connected to the hot springs. (Note how this nicely distinguishes them from any other ancient undead.)

B. Look for connections between the PCs and the bad guys.

For example, one of the PCs is a descendant of the ancient undead. (This makes the horror personal. It also provides a convenient scenario hook in keeping with the Lovecraftian literary tradition.)

C. Start with the bad guy’s plan or purpose.

Don’t worry yet about what the PCs will be doing, but leverage the connection to the PCs if possible. For example, the ancestor calls a family reunion for the extended clan at their hot spring. His goal is to transfer his consciousness to one of the younger members of the family.

D. Check your scenario seed and make sure you’ve used all the elements.

For example, we haven’t used the imagery from the Velveteen Rabbit yet. So the ancestor will give everyone coming to the reunion a reliquary memento containing a piece of one of his former bodies, enchanted so that he can track it down in the future. (Thus simplifying any future attempts to locate his descendants when further body transferrals are required.)

DEVELOP DETAILS

From this point forward, you’re simply developing the details of the spine you’ve established. (I’ll note that this shouldn’t be trivialized, however: It’s in these details where the scenario will truly come to life.) For example:

- What is the reliquary memento? A small statue made out of scrimshaw. (Why? Because it’s cool.)

- Who’s the undead ancestor? Heidvig Petersen. He was a whaler (hence the scrimshaw).

- What happens at the reunion? Nothing, actually. It’s a red herring of paranoia. The players will constantly be expecting things to go horribly wrong or explode in an orgy of violence, but Heidvig is really just scouting his potential victims.

- Is he working alone? No. Most of the employees at the hot springs are actually cultists dedicated to him. The staff may accidentally refer to him as “The One Who’s Below”.

MEDIA INSPIRATION: As you’re developing the details of your scenario, don’t be afraid to pull in more imagery and cool ideas from favorite pieces of media. (Transform them to the context provided by the spine of your scenario.)

MYTHOS LORE: Have your scenario operate consistently with or connect to other Mythos stories… unless that’s inconvenient. (For example, have Heidvig connected to Captain Marsh of Innsmouth from his whaling days. Or look at how soul transference works in Lovecraft’s stories and see how those principles could be applied to Heidvig’s ritual. For example, in “The Thing on the Doorstep” there needed to be an emotional connection.)

THE CREEPY STUFF RULE

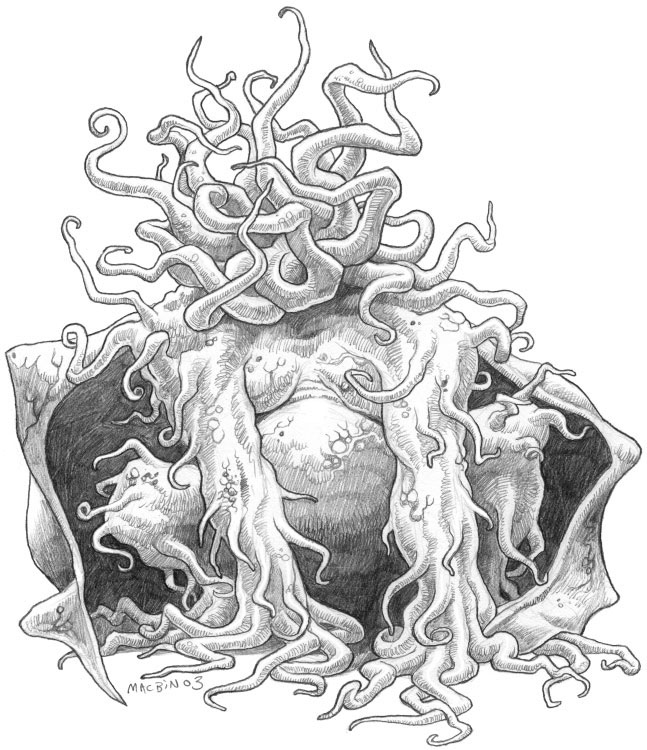

In order for creepy stuff to work, you can’t just open a random door and then be eaten by the shoggoth on the other side. You need to give your players three chances to avoid being killed by the creepy monster.

1. Hint. (Example: There’s strange slime and a viscous mud outside.)

2. Clear Indication of Danger. (Example: You find the slime-encrusted body of a dead, decapitated sewer worker.)

3. The Monster. (Example: Emerging from the sewage is a black, protoplasmic blob.)

When the bad things go down (and, since this is a horror story, bad things will go down), you want the players to blame themselves for what happens. (My note: If they externalize that blame to the GM, it becomes external not only from themselves but also from the game world. This robs the events of meaning, and without meaning there can be no horror.) With the Creepy Stuff Rule, if they’re still here, then they can’t blame you: They did it to themselves.

Petersen applies the Creepy Stuff Rule to the example scenario like this:

Hint: Heidvig’s hot-spring cooked body stalks the halls at night, leaving behind a distinctive odor of cooked flesh and, upon closer inspection, bits of boiled flesh.

Clear Indication of Danger: The PCs dicover that there are multiple levels of hidden hot springs underground, each more intense than the last. This progression leads to Heidvig’s pit, which lies adjacent to a bubbling pool of lava.

The Monster: Heidvig.

THE SOLUTION

The GM needs to come up with one viable solution to the problem they’ve created. (If the players come up with something else, more power to them.)

For example, they can throw the scrimshaw reliquary they were given into the lava pit. Its destruction will break the emotional connection between them and Heidvig, preventing him from possessing them.

In this process, revisit the points of inspiration in your scenario seed. For example, a ritual is being performed, at the end of which he will walk into the lava pool, burning his body away (like the Velveteen rabbit) and freeing his spirit to inhabit its next host. The PCs need to STOP the monster from being destroyed!

RANDOM TIPS & INSIGHTS

- When running games, Petersen will generally summarize NPC-to-NPC interactions rather than trying to talk to himself at the table. (I think the implication is that he will rarely if ever do so when the NPCs are talking to the players. Which is a technique I agree strongly with.)

- Have people see things out of the corner of their eye that aren’t there. (He takes this technique from the movie Night of the Demon, which was adapted from M.R. James’ “Casting the Runes”, in which characters keep asking the protagonist if they can take their bag or assert that the character can’t bring their dog on the train… even though the protagonist doesn’t have a bag or a dog.)

- Let the characters think they see one thing, but then it moves. (This is from “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”: Someone reaches into a niche to pull out a satchel containing the treasure… and then the satchel wraps its arms around their throat. I would generalize this to anything so alien that the mind would first interpret it as being an inanimate object.)

- Be okay with the players failing. That’s when a lot of interesting options open up.

- Give NPCs a method for disengaging from questioning. (An activity they have to do; a pager that goes off; they stop understanding English; etc.) In other mediums, the author can simply choose to end an interrogation scene. In an RPG, players tend to zero in “like a hammerhead shark” and just pound away on every NPC.

- As part of your scenario prep, think about what happens if the cops are called. (Blocking the cops from taking meaningful action is fine — the cops are cultists; the cultists can talk their way out of it when the cops show up; etc. — but try to be creative about it and be prepared for it!)

They climbed back up their rope and returned to the first major chamber they had entered after leaving the laboratories that had been inhabited by the bloodwights: The large room flanked by four massive statues of Ghul.

They climbed back up their rope and returned to the first major chamber they had entered after leaving the laboratories that had been inhabited by the bloodwights: The large room flanked by four massive statues of Ghul. In the center of the third tier, at the top of the room, there was a slab of black ebony with the appearance of an altar.

In the center of the third tier, at the top of the room, there was a slab of black ebony with the appearance of an altar.