IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

Session 6B: Return to the Depths

In which a sheen of blood signals terrors from beyond the grave, and numerous clothes are ruined much to Tee’s dismay…

This installment of Running the Campaign is going to discuss some specific details of The Complex of Zombies, so I’m going to throw up a

This installment of Running the Campaign is going to discuss some specific details of The Complex of Zombies, so I’m going to throw up a

SPOILER WARNING

for that published adventure. (Although I guess if you’ve already read this week’s campaign journal, the cat is kind of out of the bag in any case.)

Interesting conundrum:

- D&D has zombies.

- D&D can’t take advantage of the current (and long ongoing) craze for zombie stuff.

Why? Because zombies in D&D were designed as the patsies of the undead world. In the early 1970’s, when Arneson and Gygax were adding undead to their games, zombies were turgid, lumbering corpses that had been yanked out of a fairly obscure film called Night of the Living Dead. (Even Romero’s sequels wouldn’t arrive until 1978, and modern zombie fiction in general wouldn’t explode until the ‘80s.) Even skeletons, backed up by awesome Harryhausen stop-motion animation, were much cooler and had more cultural cachet.

From a mechanical standpoint, the biggest problem zombies have is their slow speed. In AD&D this rule was, “Zombies are slow, always striking last.” (Although in 1st Edition they were probably better than they would ever be otherwise, as their immunity to morale loss was significant.) The 3rd Edition modeling of this slow speed, however, was absolutely crippling: “Single Actions Only (Ex): Zombies have poor reflexes and can perform only a single move action or attack action each round.”

They were further hurt by a glitch in the 3rd Edition CR/EL system: The challenge ratings for undead creatures were calculated using the same guidelines as for all other creatures. But unlike all other creatures, undead (and only undead) could be pulverized en masse by the cleric’s turn ability. This meant that undead in general were already pushovers compared to any comparable opponent, and zombies (which were pushovers compared to other undead) were a complete joke.

(The general problem with undead was, in my opinion, so limiting for scenario design in 3rd Edition that I created a set of house rules for turning to fix the problem. There’s some evidence that these house rules are actually closer to how turning originally worked at Arneson’s table.)

In short, you could have a shambling horde of zombies (as long as the horde wasn’t too big), but it wouldn’t be frightening in any way.

Which is kind of a problem, since “horror” is literally what the whole zombie shtick is supposed to be about.

REINVENTING ZOMBIES

My primary design goal with The Complex of Zombies scenario was, in fact, to reinvent the D&D zombie into something which would legitimately strike terror into the hearts of PCs. James Hargrove described the result as, “… more or less Resident Evil in fantasy. Which rocks. And it rocks because it’s not just zombies but zombie-like things. Bad things. Bad things that eat people. Bad things that are just different enough from bog standard zombies to scare the crap out of players when they first encounter them.” Which I absolutely thrilled at seeing, because that’s exactly what I was shooting for.

One could, of course, simply have gone with a souped up “fast zombie, add turn resistance”. But I wanted to do more than that. I wanted to create a zombie-like creature that would actually instill panic at the gaming table. And the key to that was the bloodwight and its bloodsheen ability:

Bloodsheen (Su): A living creature within 30 feet of a dessicated bloodwight must succeed at a Fortitude save (DC 13) or begin sweating blood (covering their skin in a sheen of blood). Characters affected by bloodsheen suffer 1d4 points of damage, plus 1 point of damage for each bloodwight within 30 feet. A character is only affected by bloodsheen once per round, regardless of how many bloodwights are present. (The save DC is Charisma-based.)

Because the bloodsheen was coupled to a health soak ability that slowly transformed desiccated bloodwights into lesser bloodwights, the resulting creature combined both slow and fast zombies into a single package. The bloodsheen itself was not only extremely creepy, but also presented a terrifying mystery (since it would often manifest before the PCs had actually seen the bloodwight causing it).

Eventually, of course, the players should be able to figure out what’s happening and be able to put a plan of action in place to deal with it. (“Cleric in front, preemptive turning.” will cover most of your bases here.) But the design of The Complex of Zombies is designed to occasionally baffle or complicate these tactics.

Which, in closing, also brings me to another important point about using scenario design advice: I’ve had a couple different people who purchased The Complex of Zombies contact me and say, “Hey! Why isn’t this dungeon heavily xandered? Isn’t that your thing?”

Well, no. My thing is designing effective dungeons.

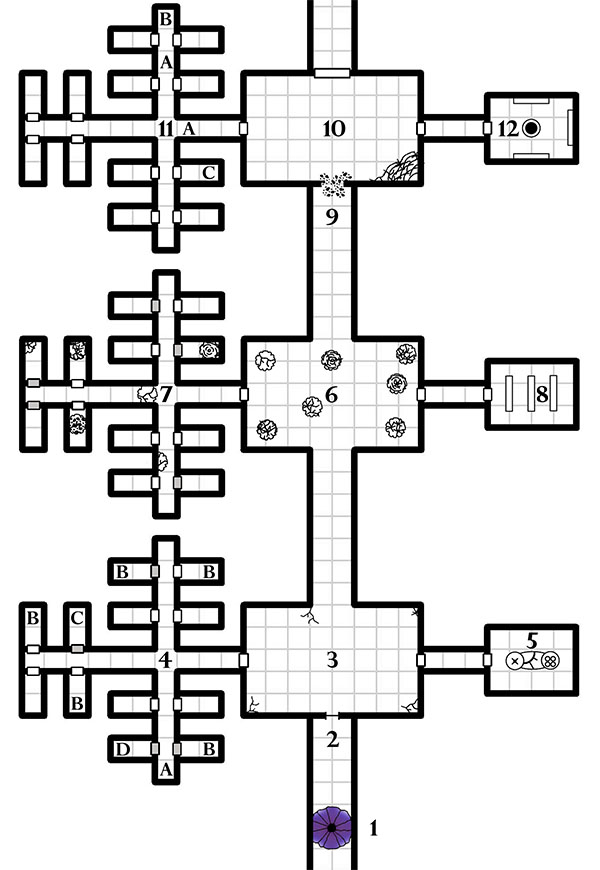

The Complex of Zombies uses a claustrophobic, branching design in order to amp up the terror. Multiple doors create “airlocks” that prevent you from seeing what’s ahead, but also cause you to lose sight of what’s behind you. Its largely symmetrical design creates familiarity and allows the PCs to benefit from “unearned” geographic knowledge, but that familiarity is subverted with terrible, hidden mysteries so that the familiar becomes dangerous. The progressive, three-layered depth of the complex meant that every step forward felt like a deeper and deeper commitment to the horrific situation. Finally, virtually every navigational decision meant turning your back on a door. (And the myriad number of doors became daunting in and of itself when the bloodsheen could be coming from behind any one of them.)

There was one stage in design where I considered linking Area 4 and Area 11 with some form of secret passage. But there are only three possible uses of such a passage:

- The players use it to “skip ahead”, which wouldn’t really give them any significant geographical advantage due to the nature of the scenario, but would disrupt the “pushing deeper, committing more” theme of the scenario. (I wanted depth in the dungeon’s design and this would have flattened the topography.)

- The players miss the first instance of the passage, but find the second. After a moment of excitement, they end up backtracking to an earlier part of the dungeon, which in most instances is going to be accompanied by the “wah-wah” of a sad trombone sounding the anti-climax as they trudge back to where they were and continue on.

- The bloodwights could use it to circle around behind the PCs and ambush them. The bloodwights were so deadly, however, that a clear line of retreat was really kind of essential for the whole scenario not to become a TPK. (There’s still a risk of this happening if the PCs don’t play smart, but that’s on the players.)

To sum up: Design guidelines are rules of thumb. Following them blindly or religiously is not always for the best. In this case, minimal xandering was the right choice to highlight the terrors of the bloodwights.

Sounds great! I’m intrigued enough to pick up the pdf!

All the updates! Did you make a New Year’s resolution or something? Eagerly catching up.

Zombies are desperately overplayed. They’ve been old and tired for years, and any game with zombies in it probably sucks automatically just for having stupid damn zombies in it.

…Probably. This here sounds pretty cool. Because, well, they’re not really “zombies”. they’re the LIVING DEAD again, frightening grotesque abominations instead of the same stupid cannon fodder with maybe a tweak here or there.

I’ve used this as part of my Ptolus Open Table (inspired directly by reading your original open table article and your megadungeon articles 5 or 6 years ago). So I actually re-engineered into part of Ghul’s Labyrinth funnily enough!

I found it worked exactly as you wanted it to – the bloodsheen freaked the players out, and the first time one of the zombies transformed, they crapped their collective breeches. This is my decade old gaming group, hardened cynics who think they’ve seen everything, who have killed hundreds of Zombies, so this was a very satisfying experience for me.

I didn’t mind that it was not “[xandered]” as I had included it as an optional sublevel in an already [xandered] dungeon (which I believe is the idea? It is sold as a mini-complex after all). The claustrophobic nature of the design was obvious to me from when I first looked at it, and my experienced dungeoneers quickly became nervous and ran out of door spikes and locks.

All in all it was a very successful wee session and very memorable for all of us. Cheers for the recommendation on Caverns of Thracia too, btw. I managed to incorporate that into Ptolus and it ran wonderfully, gave us so many hours of fantastic play. Our OT ran to level 15, and technically hasn’t fully ended, but is on a pause as people’s lives got in the way a bit.

Glad the adventure worked well for you!

For some reason I had never considered putting the Caverns of Thracia below Ptolus. Very interesting…

You said “three possible uses” and only listed two, FYI. But yeah, that seems pretty cool.

Justin,

Yeah, I made my “megadungeon” from a bunch of old dungeons I had, sort of stringing them together into one big mega-complex. I had the campaign start with the new heroes finding an unexplored section of the undercity – a buried city under Old Town, actually one of the original city’s districts. I put the Sunless Citadel in this as a starter, and then exploring the buried streets they were actually exploring the ruined city of Thracia, eventually entering the Caverns.

The temple area themselves I re-wrote as the temple of a cult to one of the Wintersouled (Thanatos) and then the caverns underneath were Ghul’s agricultural base, farmed by various slaves and home to his beast-race minions. I re-wrote the Lizard King and Minotaur King as minor lieutenants (or their descendents) and also stuck the Fortress of the Yuan Ti in there, so the large jungle cavern where the Minotaur palace is found was the farmland of Ghul’s armies, and was currently controlled by three warring factions of beast-folk.

It kept us going til about level 9 or so I think, piles of fun and very little adaptation needed really. Later adventures made use of the Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil and the Heart of Nightfang Spire.

The adventure looks fun. Hope I get to run it some day, though I want to move away from 3.5 soon.

Looks like a copy+paste error in the boxed text for section 4, it’s the same as in section 3. I’m not used to running modules, are the iron doors supposed to be open? I assume so since Lock DCs aren’t specified. Break DC are given though, I guess that is in case someone wants to break through them after wedging them shut, not that PCs need to smash them all down to progress. I also assume the map scale is 1 square to 5 feet…

I think this adventure works a little too well.

I ran it for my gaming group this weekend. As soon as they started taking damage from things they couldn’t see they started to get freaked out and a little grumbly.

They fought the first zombie and the moment they saw it was healing they freaked out and ran, barricading the door behind them.

At that point half the group wanted to simply leave the dungeon and never look back. Thus resulted a long IC and OOC argument (the kind you often find the characters participating in classic zombie movies).

One of the four players refused to go any further and waited alone at the dungeon entrance.

One player was willing to go ahead.

The other two would follow, but only after the first player had pronounced it safe.

At the first hint of combat, or the second someone took damage from blood-sheen, the party would retreat and block the door behind them.

The party got what treasure and lore they could from the dungeon with this strategy, and then retreated and did their best to start a fire that would burn down the entire complex in an effort to end the infection.

In conclusion, giving zombies a life leech aura does indeed make the players start treating the game as if it was a horror movie, but it ended up being pretty bad as a dungeon crawl.

I feel like horror-movie zombies derive most of their horror from two primary traits. First, zombies are numerous. In most horror works, one lone zombie isn’t much of a threat. The problem is that there’s never just one zombie. Get one zombie’s attention, it moans and attracts nine more zombies, each of which moans and attracts another nine zombies, and before you know where you are you’ve got a full-on horde coming at you. So one option is to deploy your zombies in much larger numbers, make it so that the players have to fear drawing the attention of hordes of zombies much too large to be defeated.

Second, and even more important, zombies are infectious. I think that’s where the true horror of the modern zombie lies, the idea of fighting an enemy where a single bite or scratch will ensure your death, put you on a ticking clock (which is usually only a few hours or at most a couple of days) until you die and are reborn as one of the very monsters you are fighting. So if you really want to capture the effects of zombie horror, I’d suggest adding that dynamic, give your zombies the ability to infect their victims with a fast-acting disease or curse that requires non-trivial expenditure of resources to cure, and that turns those it kills into more zombies. Perhaps something like mummy rot, where you have to break a curse (passing a caster level check difficult enough that remove curse isn’t guaranteed to work on the first try) before you can cure the disease. Or for that matter, remove disease is a third-level spell, so the number of clerics that can cast that more than a few times per day is pretty small. Make the disease fast-acting enough, and your cleric suddenly has to decide how many spell slots he can spare for remove disease castings when there are so many other things a third-level spell slot is needed for.

Finally, a lot of zombie horror leans heavily on the whole “collapse of civilization” dynamic, is at least as much about scavenging for resources and trying to rebuild society as it is about fighting the monsters themselves. And D&D, which is built around resource expenditure and expedition-based play, can combo beautifully with that. Make the players have to live in a world where many of the resources that are trivially available in a standard D&D game (rations, healing potions, ammunition, oil, etc.) are suddenly non-existent or difficult to get. The players can’t buy potions because none of the survivors at their camp know how to brew them (or they just don’t have the right alchemical components), so the only way to get potions is to sneak into the infested city and raid a potion shop. The wizard has to keep an eye on his material components because he can’t restock his component pouch. Etc and so on.