There are two different GMing techniques that can be referred to as “choose your own adventure”.

(If you’re on the younger side and have no idea what I’m talking about, the Choose Your Own Adventure Books, which have recently been brought back into print, were a really big thing in the ‘80s and ‘90s. They created the gamebook genre, which generally had the reader make a choice every 1-3 pages about what the main character — often presented as the reader themselves in the second person — should do next, and then instructing them about which page to turn to continue the story as if that choice had been made.)

(For those on the older side: Yes, I really did need to include that explanation.)

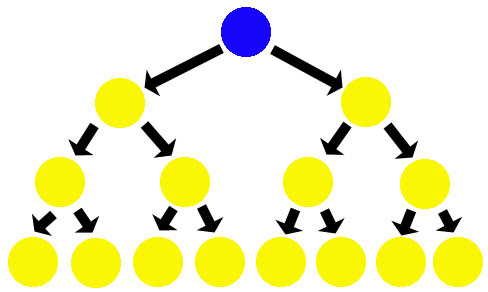

The first technique happens during scenario prep. The GM looks at a given situation and says, “The players could do A or B, so I’ll specifically prep what happens if they make either choice.” And then they say, “If they choose A, then C or D happens. So I’ll prep C and D. And if they choose B, then E or F could happen, so I’ll prep E and F.”

And what they end up with looks like this:

This is a bad technique. First, because it wastes a ton of prep. (As soon as the players choose Option A, everything the GM preps down the path of Option B becomes irrelevant.) Second, because the players can render it ALL irrelevant the minute they think of something the GM hasn’t anticipated and go with Option X instead. (Which, in turn, encourages the GM to railroad them in order to avoid throwing away their prep.)

The problem is that the GM is trying to pre-run the material. This is inherently a waste of time, because the best time to actually run the material is at the table with your players.

But I’ve written multiple articles about this (most notably Don’t Prep Plots and Node-Based Scenario Design), and it’s also somewhat outside the scope of this series.

What I’m interested in talking about today is the second variety of Choose Your Own Adventure technique, which I suppose we could call:

RUN-TIME CHOOSE YOUR OWN ADVENTURE

GM: You see that the wolf’s fur is matted and mangy, clinging to ribs which jut out through scrawny skin. There’s a nasty cut along its flank. It snarls menacingly at you. Do you want to attack it? You could also try offering it some food.

With run-time choose your own adventure, in addition to describing a particular situation, the GM will also offer up a menu of options for how the players can respond to it. In milder versions, the GM will wait a bit (allowing players to talk through a few options on their own) before throwing in his two cents. In the cancerous version, the GM will wait until a player has actually declared a course of action and then offer them a list of other alternatives (as if to say, “It’s cute that you thought you had autonomy here, but that’s a terrible idea. Here are some other options you would have come up with if you didn’t suck.”).

It can be an easy trap for a GM to fall into because, when you set a challenge for the PCs, you should be giving some thought to whether or not it’s soluble, and that inherently means thinking through possible solutions. It’s often very easy to just burble those thoughts out as they occur to you.

It’s also an easy trap to fall into during planning sessions. Everyone at the table is collaborating and brainstorming, and you instinctively want to jump into that maelstrom of ideas. “Oh! You know what you could do that would be really cool?”

It’s also an easy trap to fall into during planning sessions. Everyone at the table is collaborating and brainstorming, and you instinctively want to jump into that maelstrom of ideas. “Oh! You know what you could do that would be really cool?”

But you have to recognize your privileged (and empowered) position as the GM. You are not an equal participant in that brainstorming:

- As an arbiter of whether or not the chosen action will succeed, you speak with an inherent (and, in many cases, overwhelming) bias.

- You’ve usually had a lot more time to think about the situation that’s being presented (or at least the elements that make up that situation), which gives you an unfair advantage.

- You often have access to information about the scenario that the players do not, warping your perception of their decision-making process.

The players, through their characters, are actually present in the moment and the ideas they present are being presented in that moment. The ideas that you present are interjections from the metagame and disrupt the narrative flow of the game.

Because of all of this, when preemptively suggesting courses of action, you are shutting down the natural brainstorming process rather than enabling it (and, in the process, killing potentially brilliant ideas before they’re ever given birth). And if you attempt to supplement the options generated by the players, you are inherently suggesting that the options they’ve come up with aren’t good enough and that they need to do something else.

So, at the end of the day, you have to muzzle yourself: Your role as the GM is to present the situation/challenge. You have to let the players be free to fulfill their role, which is to come up with the responses and solutions to what you’ve created.

As the Czege Principle states, “When one person is the author of both the character’s adversity and its resolution, play isn’t fun.”

But more than that, when you liberate the players to freely respond to the situations you create, you’ll discover that they’ll create new situations for you to respond to (either directly or through the personas of your NPCs). And that’s when you’ll have the opportunity to engage in the same exhilarating process of problem-solving and roleplaying, discovering that the synergy between your liberated creativity and their liberated creativity is greater than anything you could have created separately.

WITH NEW PLAYERS

This technique appears to be particularly appealing to GMs who are interacting with players new to roleplaying games. The thought process seems to be that, because they’re new to RPGs, they need a “helping hand” to figure out what they should be doing.

In my experience, this is generally the wrong approach. It’s like trying to introduce new players to a cooperative board game by alpha-quarterbacking them. The problem is that you’re introducing them to a version of a “roleplaying game” which features the same preprogrammed constraints of a board game or a computer game, rather than exposing them to the element which makes a roleplaying game utterly unique — the ability to do anything.

What you actually need to do, in my general experience, is to sit back even farther and give the new players plenty of time to think things through on their own; and explicitly empower them to come up with their own ideas instead of presenting them with a menu of options.

This does not, of course, mean that you should leave them stymied in confusion or frustration. There is a very fine line that needs to be navigated, however, between instruction and prescription. You can stay on the right side of that line, generally speaking, by framing conversations through Socratic questioning rather than declarative statements: Ask them what they want to do and then discuss ways that they can do that, rather than leading with a list of things you think they might be interested in doing.

WITH EXPERIENCED PLAYERS

You can, of course, run into similar situations with experienced players, where the group has stymied itself and can’t figure out what to do next. When you’re confronted with this, however, the same general type of solution applies:

A few things you can do instead of pushing your own agenda:

- Ask the players to summarize what they feel their options are.

- In mystery scenarios, encourage the players to review the evidence that they have. (Although you have to be careful here; you can fall into a similar trap by preferentially focusing their attention on certain pieces of information. It’s really important, in my experience, for players in mystery scenarios to draw their own conclusions instead of feeling as if solutions are being handed to them.)

- If they’ve completely run out of ideas, bring in a proactive scenario element to give them new leads or new scenario hooks to follow up on.

Also: This sort of thing should be a rare occurrence. If it’s happening frequently, you should check your scenario design. Insufficient clues in mystery scenarios and insufficient scenario hooks in sandbox set-ups seem to be the most common failure points here.

This problem can also be easily mistaken for the closely related situation where the group has too many options and they’ve gotten themselves locked into analysis paralysis. When this happens, it should be fairly obvious that tossing even more options into the mix isn’t going to solve the problem. A couple things you can do here (in addition to the techniques above, which also frequently work):

- Simply set a metagame time limit for making a decision. (Err on the side of caution with this, however, as it can be very heavy-handed.)

- Offer the suggestion that they could split up and deal with multiple problems / accomplish multiple things at the same time.

The latter would seem to cross over into the territory of the GM suggesting a particular course of action. And that’s fair. But I find this is often necessary because a great many players have been trained to consider “Don’t Split the Party” as an unspoken rule, due to either abusive experiences with previous GMs or more explicitly from previous GMs who don’t want to deal with a split party. That unspoken rule is biasing their decision making process in a manner very similar to the GM suggesting courses of action, and the limitations it imposes often result in these “analysis paralysis” situations where they want to deal with multiple problems at the same time, but feel that they can’t. Explicitly removing this bias, therefore, solves the problem.

You can actually encounter a similar form of analysis paralysis where the players feel that the GM is saying “you should do X”, but they really don’t want to. Or they’d much rather be doing Y. And so they lock up on the decision point instead of moving past.

Which, of course, circles us back to the central point here: Don’t put your players in that situation to begin with.

Your example of what not to do reminds me of the Heroes of Battle supplement for 3.5. In their advice on how to plan a battle, the authors recommended setting up each battle as a flow chart with multiple decisions springing from each encounter the PCs chose. It was apparent on first reading that the intent was (1) that PCs might ignore whole sections of the flow chart and (2) the PC options were foregone conclusions (they would either kill the commander or interrogate him at camp – nothing about using a charm to stall the enemy, etc.). In practice it proved unwieldy and unusable.

Red Hand of Doom did a much better job of a “war” campaign; while the book is not without it’s flaws it remains one of my favorite adventures I’ve ever run.

This is timely advice. For his tenth birthday party I’m running a Star Wars adventure for my son and his friends. (Using West End Games’s d6 system.)

I have an adventure mapped out, and it’s pretty free-form. However, it’s good to be reminded to resist the temptation to try and offer suggestions to the boys on how to deal with the obstacles I put in their path.

This article and it’s methods seem interesting to me as another GMing tool Justin, but after reading I’m not entirely convinced it should be put into the “Do not GM this way” section.

It does seem a good tool for GM’s who are seeking a certain type of play though.

But what I GET from you putting this into the “Do not GM this way” section is that when a GM does do this… the game they are running is somehow fundamentally flawed, they are inhibiting the roleplaying in a roleplaying game, or they aren’t playing a roleplaying game at all but instead a choose your own adventure game.

I don’t agree with that idea which is what I got from reading this article.

I’ve been thinking about how to phrase it all but along with everything else that is concerned with choices in games such as consequences and whether or not a choice is really doing anything, I don’t think that simply saying “never suggest an option except in the cases when they are completely lost” is completely correct.

Or simply put another way I guess…if choices represent roleplaying in roleplaying games at all, where exactly is that roleplaying within the context of making a choice? Is it in determining approaches or making an approach yourself? Is it in choosing which of the consequences to accept as well as approaches or merely in the intention alone?

Furthermore, if anything I also believe simply saying “Don’t suggest a course of action at all” is simply impractical to the point of being silly. I realize this might not be what you are saying but it should be said nonetheless before someone reads this and begins not suggesting anything anywhere.

There ARE different levels of choices, meaning choices on action levels, encoutner levels, adventure levels, and campaign levels.

So to say to not suggest anything anywhere in total like i said to me seems pretty silly. I’m not suggesting any action…I’m not suggesting any means to get to the goal of an encounter, adventure, and I’m also not suggesting any campaign decisions at all.

Some before have said that suggesting for adventures is good adventure design.

Furthermore, there’s also the idea of not detailing consequences to consider. I have seen a roleplaying game happen where a consequence was not detailed during the choice, and then afterward the consequence was improvised and a player had to go along with it. I tend to think that some might like it and some might not?

I notice you said nothing about this in this article and might have talked about consequences in another article, but some reading this might think oh whenever they make a plan I don’t have to tell them about any consequences of that plan. Especially since they haven’t come up with any other options to compare with. Depending on what players or GM’s might want I think this might or might not be something to consider.

Also, some people might not want to even play in a roleplaying game where there is ANY thinking about how to form their own approaches to situations, but rather might like roleplaying games in which they solely choose between listed options. I believe that many – myself included – would consider in those games that roleplaying HAS occured and that the choices were interesting and that the roleplaying was fun.

I think I’ll say finally though again what I disagreed with above, which is the idea that because a GM is suggesting there is no roleplaying happening and you are now in a choose your own adventure game.

The only reasoning in THIS article is that because a GM suggests things this leads to players not being able to come up with things themselves.

I firmly believe this is not the case, having seen players in my games come up with choices despite me listing options, and having been a player myself.

Or rather…I tend to agree more with the idea that when a GM suggest options, players CAN still come up with their own.

To say that suggesting is wrong because they can’t come up with their own if you do, yes I must disagree with that.

I think this subject might deserve more consideration, and it’s an interesting subject to ponder for me.

You seem to be very concerned about people reading things I didn’t actually say (and often said the exact opposite of ) while reading this essay. I am less concerned about this than you are.

Alex: “Or rather…I tend to agree more with the idea that when a GM suggest options, players CAN still come up with their own.”

With that being said, this is a vastly over-simplified version of what I said. In fact, I would characterize it as being so simplified as to be a complete misrepresentation of what I said. (Particularly since I did, in fact, say the exact opposite.)

As I said in the essay: The GM has a privileged and empowered position (due to their authority, their exclusive knowledge, and the extra time they’ve had to think about the situation, among other things). Their suggestions bear the weight of that privilege and power, which systemically and INEVITABLY warps the brainstorming process. Warping the brainstorming process in this way is BAD (for all the reasons spelled out above), but it does not, as you suggest, completely shut it down.

If you are, in fact, frequently suggesting courses of action to your players, do yourself a favor and try experimenting with NOT doing that for a few sessions. Let your players actually play the game. You’ll most likely be able to immediately see a change in the quality of play.

Interesting to ponder…

“Their suggestions bear the weight of that privilege and power, which systemically and INEVITABLY warps the brainstorming process. Warping the brainstorming process in this way is BAD (for all the reasons spelled out above), but it does not, as you suggest, completely shut it down.”

Yes I’m still disagreeing with the above. Maybe I’m wrong….

So there’s three things in that statement and another thing in the article that I think we might be able to express thoughts about.

So for discussion lets say a GM suggests options and definitely does warp the brainstorming process as you say.

I disagree that warping the brainstorming process in that way for that situation is completely bad. As I said above the are other choices in the game to consider.

For example, if a GM has not suggested any options in all other choices in a game and then suggests options for one choice and only this one…I do not believe that is BAD because they still have great control over the story with all of the other choices. Now let’s say it’s half and half – half suggesting and half not. I still don’t think this is BAD because yes they still have definite control over some parts. Maybe there’s a level for each group or each situation. I often think that if there is at least 1 or 2 situations where you don’t suggest anything that the game would be satisfactory.

More on this idea that it might not be bad. Not for the sake of argument but I’d like to ask you this question.

Can you think of any situation where interrupting a players brainstorming process might be beneficial?

I think that in certain situations or seeking something else from play that it might be acceptable.

For example…immersion. I would assert that to help maintain immersion a GM can suggest options that are reasonable within the context or the situation so as to say “Hey these are the things that are reasonable within the situation so that you can immerse yourself in the environment I am describing and the situation more readily. If your character wants to think about things that is fine as well.”

I would also assert that pausing at every decision point and having every player at the table begin brainstorming can inhibit immersion in certain situations.

Secondly, I’d like to say things about the idea that suggesting options systematically and inevitably warps the brainstorming process.

I see no reason why a GM can suggest things in one situation and then can’t suggest things in another like you are saying. IF that does happen…has the brainstorming process been warped? I don’t think so…if you think so how do you think it has been?

Thirdly, there might be situations where the GM does NOT have the privilege and power that I think is assumed.

A GM might be completely improvising a scene and everything else on the fly, so in effect they might also be brainstorming about solutions for a problem.

I think another less occurring example might be cases where there is GM PC playing as well. Should the GM PC simply not suggest anything? I don’t think so.

I guess there’s one more thing I wanted to converse about. In my first response I was talking about if there is roleplaying in the context of a choice, where did it happen?

When you say warping the brainstorming process is BAD, I’d like to ask you more about why?

Interjections from the metagame…why? I think there are cases where simply describing things IS a strong suggestion. For example a room in a dungeon with 2 exits. As a GM, however you describe the two exits you are probably also suggesting that the players can begin traveling through those exits.

I.E “There is an exit which leads to spiders and an exit which leads to bugbears.” Even though the GM didn’t say you COULD walk through those exits, I think it is implied.

I also think that if a GM does say you can exit through those, that this does not disturb the brainstorming process….”There are two exits that you CAN exit by, one leading to spiders and one leading to bugbears. You could also decide on another course of action…”

Some would way say that providing suggestions enhances the narrative flow of the game rather than disturbs it, because it can help to provide a better story when there are options toward a goal. Why do you think it might disturb narrative flow?

But moreover and related to question of where the roleplaying is…is the brainstorming itself what we are after? I’m asking this because some people might not think that for every situation it is really roleplaying when a GM says what do you do and then players have to stop, consider all of their tools, and effectively think about a solution. In other words, some might not think that the players THINKING equates to what we are after.

The last thing I wanted to ask about is…

” And if you attempt to supplement the options generated by the players, you inherently suggesting that the options they’ve come up with aren’t good enough and that they need to do something else.”

Okay, let’s go with something I might actually consider doing and consider fine.

I say to my players commonly before and after game sessions “It’s okay if you want to come up with something else”

I also say after suggesting options “Or you can try something else that you’ve thought up or can come up with something else”

If I say those things and remind them they can still come up with something else, why do you think that when I am suggesting I would be saying that they’re choices are not good enough?

This seems like an out of game discussion where you treat people like people and simply say “Hey listen, I consider your solutions to things just as good as mine.” Then that’s that.

@Alex

I think you exagerate the points made by Justin in some places, but I think that your first (and, I’d say, main) criticism is based on a fair understanding of the article : “But what I GET from you putting this into the “Do not GM this way” section is that when a GM does do this… the game they are running is somehow fundamentally flawed, they are inhibiting the roleplaying in a roleplaying game, or they aren’t playing a roleplaying game at all but instead a choose your own adventure game.”

I can’t talk for Justin, but that’s roughly what I gather from the article. I also agree with it, so I disagree with you.

Of course, anyone can do whatever they want when they game. I’m not here to tell you that you have bad wrong fun. Maybe you play with people who “might not want to even play in a roleplaying game where there is ANY thinking about how to form their own approaches to situations, but rather might like roleplaying games in which they solely choose between listed options”. Maybe you are such a person yourself. All fine, keep doing that if you like it.

But this blog is a place where Justin try to articulate what makes a roleplaying game better or worse. His contention is that the best part of tabletop RPG is the ability to basically try anything; it’s the best part because it’s the part that distinguish it from other kinds of games. Thus, presenting a menu of choices hamper this (even if it does not entirely cancel it); actually saying that presenting a list of choices does not bar a player from suggesting somthing else supposes that an important and valuable part of play is actually coming up with original, unanticipated ideas.

You ask “if choices represent roleplaying in roleplaying games at all, where exactly is that roleplaying within the context of making a choice? Is it in determining approaches or making an approach yourself?” Since roleplaying is playing the character as if you were yourself in the situation, it’s better served if the DM only gives informations the PC would have access to. So giving a list of predetermined choices is usually worse for roleplaying.

Sure, maybe some people like their RPG where their choices are predetermined. To those, I simply say : all the power to you, do as you wish, it’s your game. But they basically choose to check out of this conversation, in the same way that, say, someone saying they don’t like coconut much check out of the conversation about how to make the best coconut pie.

So in the interest of this conversation, I’d ask this : in what sense a DM presenting a list of choices, choose-your-own-adventure-book style, makes an RPG experiences better?

As an aside, this reminds me of the Elite Dangerous RPG kickstarter video. It presents a “story”, sometimes interrupted by screen saying “your next move?” and a list of choices, that continue once one is highlighted (it’s not interactive; the video chooses one as if the player did). It really felt like a computer RPG, and I thought that they really had a bad way of presenting their tabletop game. (It raised almost 200% of its goal, so a lot of people did beg to differ!)

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/edrpg/elite-dangerous-role-playing-game

@Alex

My previous comments were written before your answer was made visible.

Now that I read your second comment, here are my thoughts :

1. You seem to understand good and bad as binary states, where something not entirely bad is good. Think more of a continuum, in terms of better or worse instead of good and bad. “I disagree that warping the brainstorming process in that way for that situation is completely bad.” Well, maybe not completely bad (what would that look like?), but surely worse. That’s what the article is about : don’t GM like this or your game will be worse.

2. I’m not sure we understand “a GM gives a list of choices” the same way. You suggest that when the GM says that there are two doors, he also suggests some choices to the PCs. It’s clearly not an instance of giving a list of choice. The GM simply describes what the PCs perceive. A good example would be the GM saying “the door is locked, but you could try to force it open or you could pick the lock”.

3. Actually, there are quite a lot of concepts I feel we use differently. You write this : “I’d like to say things about the idea that suggesting options systematically and inevitably warps the brainstorming process. I see no reason why a GM can suggest things in one situation and then can’t suggest things in another like you are saying. IF that does happen…has the brainstorming process been warped?” But by “inevitably warping the brainstorming process”, I understand that the very action of presenting a list of choice to players warps the process, not that the GM is somehow

always presenting a list of choice. When the GM does it, he inevitably warps the process, but not when he does not.

Same goes with the “privilege and power” of the GM. It’s derived from his position as GM, where his decisions are laws. Even when he improvises, if he suggests a choice, the players have a pretty good reason to assume that this idea have a reasonable chance of success. Plus, the players don’t always know when the GM improvises and when he does not. Imagine, if you will, a job interview where the interviewer asks a question, then suggests a list of answers to the interviewee. Even if he then adds “sure, you can answer something else”, and even if the interviewer is genuinely open to other answers, the interview is pretty skewed toward the choices presented.

4. Immersion and roleplaying… I don’t know, it’s like we understand those things in completely opposite manner. Immersion the feeling I have when I forget I’m at a table with my friends and act as if I were my PC; when the GM gives a list of options I can take, I’m out of the game world and back at the table where, so that breaks immersion by definition. Roleplaying is playing as if I was my character; thinking through a problem is very much part of roleplaying. If my PC faces a challenge, but I don’t have to think about it because I can choose from a menu of choices, I am clearly roleplaying less, not more! Thats why computer RPG, all great they can be, don’t offer the roleplaying experience a tabletop RPG can : they are limited by what the designers coded, by what choices they gave the players.

@Gamosopher

(And maybe Justin)

Ahh okay…

Let’s shift “styles” here so as to remake the focus into what I was asking in my second post.

1.) “That’s what the article is about : don’t GM like this or your game will be worse. ”

Why would the game be worse?

Consider this simplified example…

Encounter #1 – GM lists a menu of options adding that any other options from the players are fine.

Encounter #2 – GM does NOT list a menu of options and forces the players to come up with one or more.

Question:

Why is the brainstorming process affected at all?

I could explain what I meant with the immersion or other things similar to that – tbh I regret using immersion because it isn’t really clear or unclear.

Instead I’ll go with the most basic one right now which I believe is when people are thinking about the solution they might as well be considered “gorming around”.

Example I can easily imagine…

*A GM describes a situation without giving any options, afterward..* “What do you do?”

Players: “Hmmm…” *For a few seconds*

Players: “Wait a second, what CAN we do?”

*Everyone proceeds to think about what they can do…*

Why is the game better, and not worse? Aside – some might say that that is worse in certain situations.

2.) You know what…I could explain what I meant by the 2 exits but let’s forget about that for simplicity. Let’s just continue with asking why? Why would anyone think these options from the gm warp the brainstorming process?

3.) For gamosophers response to what I said, if he added the very next sentence I ask why…

So again, why would anyone think it might disturb the process?

@Gamosopher

4.) “If my PC faces a challenge, but I don’t have to think about it because I can choose from a menu of choices, I am clearly roleplaying less, not more!”

Why do you think this way gamosopher? If anyone else thinks this way…why?

@Alex

In your comment #9 (the last one I can read while typing this), you ask how the GM giving a menu of options warps the players’ decision making. It’s pretty hard for me to answer this question differently from what was already said, but I’ll try. The argument goes basically like this :

1. A decision is taken freely when there is no authority suggesting some avenue.

2. A GM has basically supreme authority on what happens in the game world.

3. Thus, a GM suggesting a menu of options makes the PCs decision less free, and so warps the decision process.

My first claim is general, not specific to RPG. I think it is well illustrated by my analogy with a job interview. The very fact that someone with great authority suggest a solution to a problem makes this solution weightier. There is a reason brands and political candidates want the endorsement from celebrities : they are taken as a form of authority by the public, so when they suggest a product or a candidate is great, it bias the public towards this opinion.

My second claim is pretty self evident once you understand what a GM is. The third claim is deduced from the two first ones.

You could say that it is sometimes better to bias the players’ decisions towards some avenues. For example, in a mystery, you could argue that it is better if the PC choose amongst a couple of valid leads instead of following a ridiculous pet theory of their own that, as a GM, you know will yield no information of value and will go nowhere (will eating table time). But I think this limits the act of roleplaying, which is bad when you play a roleplaying game. As a GM, you see a valid problem (the PCs make very bad decisions), but the solution is to make the game a bit less of a roleplaying game (bias their decisions). Justin rightly suggests that you should instead embrace those “bad” decisions and run with them (let them fail, if that is what should happen; but along the way, there might be awesomeness involved), but also make sure your game is prepped in a way that don’t break when players make “bad” decisions. But that’s for another post : if you’re interested, have a look at the articles on the “Gamemastery 101” page, linked in the right hand bar, near the top of this blog.

You also ask, in comment #9, why choosing amongst a menu of ideas means less roleplaying than coming up with your own ideas. Here, again, it’s pretty hard for me to explain, since I think it’s almost self-evident. It’s why an RPG videogame like Mass Effect or Skyrim or The Witcher or Fallout have always less roplaying potential than tabletop : all the choices the player make must be allowed by the program. You can pickpocket a guard in Skyrim because the developpers put that mechanic in the game; but if you want to burn a wooden wall to the ground, you can’t (even if that would make perfect sense) if the dev did not allow it in the mechanic. It’s even clearer when you think of dialogue options that are features in most RPG videogames. What involves the most roleplaying : choosing one of 5 dialogue options, or saying precisely what you would say in this situation? Since roleplaying is acting as if you were in the situation, and since, if you were discussing with an NPC, you would not have dialogue options presented to you but would have to actually talk in your own words, it’s clear that a list of options means less roleplaying.

So the main argument goes like this :

A. A GM suggesting a list of options warps the players’ decision making.

B. The essence of roleplaying is making decisions.

C. Thus, a GM should not suggests a list of options when the PCs are confronted to a situation, but simply describes what the PCs perceive.

@ Alex

I’ll add one last thing to my already too long comments. In #9, you gice this example :

“*A GM describes a situation without giving any options, afterward..* “What do you do?”

Players: “Hmmm…” *For a few seconds*

Players: “Wait a second, what CAN we do?”

*Everyone proceeds to think about what they can do…*

Why is the game better, and not worse? Aside – some might say that that is worse in certain situations.”

You seems to assume that the choices the players will come up with would be the same, whether the GM don’t give any to start with (as in this example) or does. But this is not the case; Justin’s article is about that.

Take the concrete example of the PCs encoutering a locked door. If the GMs immediately says “you could try to force it open or you could pick the lock”, the players’ decision process is warped, because it’s immediately biases towards those options. Sure, it’s possible players will come up with other ideas; but it’s less likely they’ll be sparked, because theit mind is already set to the options provided by the GM, and less likely they would be chosen if they come up, because they will always be weighted against the GM’s suggestions. If the GM don’t say anything, the chances that some crazy ideas come up is higher : maybe one will suggest to burn the door down, or put acid in the lock, or carve a peephole, or something else entirely. And that’s just for a pretty simple choice about a locked door : it snowballs and becomes really important once you take into account the fact that any situation is an opportunity fot the PC to make a choice.

That’s why a list of choice make a roleplaying game worse, not just as good, and definitely not better.

@Alex

You say : “Instead I’ll go with the most basic one right now which I believe is when people are thinking about the solution they might as well be considered ‘gorming around’.” This perfectly encapsulates our disagreement.

If thinking – as characters – about the solution of a problems is some kind of waste of time for you, we fundamentally disagree about the nature and fun of a roleplaying game. I’d say this is the very core of the experience, of what makes an RPG different from other games. As a player, when I feel my choices are arbitrarily constrained by the GM (whatever the reason), or when my choices appears to be mostly irrelevant to direction the story takes, my experience is less fun, and I’m wondering why I’m not playing a game better suited to this kind of play (like a good boardgame or videogame).

@Gamosopher

“1. A decision is taken freely when there is no authority suggesting some avenue.”

Why do you think this?

I notice that this is repeatedly asking why but I kind of feel you answered a questionable statement with the same statement.

Or in other words I asked “Why does a gm suggesting warp the players decision making process”

and then you answered with “Because an authority suggesting warps the decision making process”

Why?

“2. A GM has basically supreme authority on what happens in the game world.”

I disagree completely and consider this statement to be wrong. If you disagree I’ll be happy to discuss it.

Another point…

“You also ask, in comment #9, why choosing amongst a menu of ideas means less roleplaying than coming up with your own ideas.”

Okay let’s go back to the statement to see…

“@Gamosopher

4.) ‘If my PC faces a challenge, but I don’t have to think about it because I can choose from a menu of choices, I am clearly roleplaying less, not more!’

Why do you think this way gamosopher? If anyone else thinks this way…why?”

First of all I’d like to point out a few things about that last statement.

A.) You say “If my PC faces a challenge, but I don’t have to think about it because I can choose from a menu of choices…”

However, I would assert a more accurate change to that statement.

When you are presented with options you DO have to think about them as your character IF you are kind of playing the game.

The only thing I can come up with as an exception is that your character simply hates considering options. Though I think – and assert – that might be the exception.

Otherwise, let’s just assume that when players are asked questions at all they don’t think as their character and instead roll dice to determine their PC’s actions.

Or everyone can just understand that yes…when players are presented with choices they actually DO still THINK about the choice.

B.) Finally, the statement actually has the word CAN.

“If my PC faces a challenge, but I don’t have to think about it because I *emphasis mine* CAN choose from a menu of choices…”

Given that your response to it went over how video games and other menu option games are TRULY constrained…

Can you see how that is not true in the statement I asked about? Rather, the players truly are not constrained to only the menu options.

If you’d like to discuss the A) or B) section we can, but I’d actually like to move it back to the following…

HOWEVER!

Given your previous assertions on question number one, I believe I can understandably see the reasoning that leads one to believe in all of that.

Basically…menu options actually DO constrict choices and freedom AND that is why they provide less “roleplaying”.

If that is a correct understanding of the line of reasoning, again…WHY do you believe that suggestions constrict choices and freedom?

Final point….

” As a player, when I feel my choices are arbitrarily constrained by the GM (whatever the reason), or when my choices appears to be mostly irrelevant to direction the story takes, my experience is less fun,…”

I did not at any point maintain that players should not be able to affect the storyline – in fact they actually CAN with a menu of choices.

But I do think I am still asking about why you think the actual constraining by the GM is happening?

Why are suggestions by the GM constraining or limiting?

Oh and I forgot to add this because the page accidentally left when I wrote before…

Another point…

“Take the concrete example of the PCs encoutering a locked door. If the GMs immediately says “you could try to force it open or you could pick the lock”, the players’ decision process is warped, because it’s immediately biases towards those options.”

I love this example. But I think you are wrong about something…

I assert that – in a “generic” sense – it is NOT the GM coming up or even suggesting these options.

It is instead the TOOLS or the CHARACTER SHEET.

Meaning that its not the GM who came up with the idea…it’s the lockpick skill and the strength score on the character sheet and the default rules given.

First of all, I don’t think anyone is asserting that when a GM reminds a player how they can use their character, that they are doing so with a detrimental ulterior motive. A “Dishonest helping hand” from the GM if you will.

In game example…

Player: Hmmmm…I have a lockpick skill but forgot what it can do? GM?

GM: Oh of course I’ll help remind you. The lockpick skill can pick the lock on the door.

Player: Ahh thank you very much GM.

However, it is interesting to note I think that it actually originated from the RULES and not the GM. Aside – maybe it can originate from other things to?

IF you think that the above example is bad. Why? If not, does the answer to suggestions change or become edited in some way?

@Alex

Well, I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree on pretty much everything. I really tried to understand your point of view and explain mine, but your last comments made me realize that it’s probably better to stop trying.

You say : “I notice that this is repeatedly asking why but I kind of feel you answered a questionable statement with the same statement. Or in other words I asked ‘Why does a gm suggesting warp the players decision making process’ and then you answered with ‘Because an authority suggesting warps the decision making process’. Why?”

Well, I provided two examples, in my opinion solid ones (job interview and celebrity endorsement), to illustrate it. You did not explain why they did not convince you, or how they were wrong, or even aknowledge I did provide them. So : reread my previous comments. Besides, as I already said, it’s pretty obvious that when someone with authority over you suggest you take some specific actions, your decision making is biased towards those actions. If you really want to be technical about it, you can look up “authority bias”, or even the psychological bias known as “anchoring”, where suggesting choices warps the decision making process even if no kind of authority is involved.

You say that you “disagree completely” with my statement that a GM has basically supreme authority on what happens in the game world”, and consider it simply “wrong”. Maybe we could argue about the degree of authority a GM has (constrained by rules, previous decisions, player input and decisions, etc.), but all of this is inconsequential to the thrust of my argument. You also, weirdly, don’t explain yourself, instead telling me this : “If you disagree I’ll be happy to discuss it.” Well, of course I disagree : you are literally saying that what I just was wrong without providing any argument. What did you expect?

Your whole answer about how a list of choices does not constrain players’ choice (A and B) strikes me as beside the point. Justin’s article says that you should not, as a GM, present a situation and then provide a list of options, because that warps the decision process. It does not completely cancel it, everyone agrees. I already said (comment #8) that a mistake you seem to commit is to think in a binary way (good vs bad) instead of better and worse. Yet, you respond that “the players truly are not constrained to only the menu options”. That’s not what anyone is saying. I already explained (as did Justin) why the simple act of giving providing a list, even along the heartfelt aknowledgement that PC can suggest other ideas, warps the decision process. Reread my previous comments.

You then restate my point like this : “menu options actually DO constrict choices and freedom AND that is why they provide less ‘roleplaying’.” That’s pretty much what I said, yeah; but you then ask me “WHY do you believe that suggestions constrict choices and freedom?”… which I did, while explicitely saying I was doing it, in my previous comments. So : reread carefully what I already wrote.

You finish your comment #13 like this : “But I do think I am still asking about why you think the actual constraining by the GM is happening? Why are suggestions by the GM constraining or limiting?” Again, reread what I wrote, and reread Justin’s article.

Then, in comment #14, you completely change the subject. A player looking at his PC sheet, or asking the GM to clarify what some things on it means, is clearly not a case of the GM giving a menu of choices. If the GM says (as my example states) “you could try to force it open or you could pick the lock”, he literally provides a list of choices, and thus warps the decision making process. If he does not, but then a players asks “I have a lockpick skill but forgot what it can do? GM?” (as your example states), well, the GM does not provide a list of choice, and does not warp the decision making process. Don’t you see the difference? Your whole comment #14 is beside the point.

I think I made my case sufficiently clear : you last questions are already explicitly answered in my previous comments. If you want, you can try to explain how providing a list of choices, as a GM, makes the roleplaying experience better, or at least don’t make it worse. Maybe we then could go on having a productive discussion.

Good we actually got somewhere. Yes I actually do disagree right now that a GM suggesting options hampers the decision making process in some way.

Maybe I will look at this anchoring or authority bias and thing and see what I think of it.

I’d like to thank Justin for having and operating this website where we can actually discuss such things and Just and gamosopher for having this discussion with me.

Okay after having read about authority bias and anchoring for a few minutes I disagree that they apply to GMing.

If you want reasons from what I have read anchoring is almost specifically about numbers and negotiations for prices, which IMO does not relate – in any way – to a menu of options from the GM.

For authority bias as I said I don’t believe that the GM is considered an authority on what people should have their characters do in RPGS, but moreover it’s because in the original Milgram experiment it was simply one thing that the presenter was telling a person to do, with reassurances and with repetition on the part of the suggester. I do not believe this applies to GM’s providing a menu of options.

But another thing I noticed about this is that while reading that thing about authority bias, it is obvious that alot of it has to do with the GM actually recommending an option. Expressing favor toward one of the options over the other. Saying “hey players, this option is clearly better than this option.”

I noticed that we are using “A menu of options” and “GM’s suggesting” interchangeably, and although suggestions could mean simply putting forward for consideration, some might actually think it means that a GM is recommending things.

Furthermore, the article basically says this all about “A menu of options”

I would like to point out now that when a GM lists a menu of options before the players, a GM is NOT recommending any of the options, expressing favor toward one of them, or saying “Hey players the options I listed are what I recommend for you and they are what I would do in this situation.”

They are merely possibilities for the players.

I actually thing that from what I’ve experienced, the players asking the GM how they would play is quite rare. I don’t think it’s ever happened to me.

Thus, the idea of authority bias happening is IMO thrown out simply because it really isn’t a recommendation from the GM, but a GM listing a few possibilities.

I’ve been having fun discussing things here gamosopher and hope anyone else concerned has been too…

But in the spirit of more fun hehe.

“…If you disagree I’ll be happy to discuss it.” Well, of course I disagree : you are literally saying that what I just was wrong without providing any argument. What did you expect?”

Don’t take this in any detrimental way anybody as I don’t mean it that way.

Honestly…I expected you to recant immediately. Hehehe in my dreams right.

Something like “Oh actually yeah Alex you are completely right in that GM’s don’t have total control over what happens in the game world”

I’ve never met a GM who I thought would endorse that statement.

Honestly…consider me SURPRISED.

@Alex

I’m afraid for my poor dominion of English. Whatever. Back in my days, the modules I used to play were way *less* interactive than a run-of-the-mill CYA book. Modules were written like a lousy shitty fan-fic with stat blocks.

Teoretically we the players could try *anything*. Practetically there was just One Answer To Rule Them All, and the module wouldn’t go on unless we the players figured it out The Answer – or the GM got bored and tell us what to do.

On the upper side, The Right Answer was totally straightfordward: orcs attack your party, what will you do? (uh, let me guess, killing the orcs maybe?). There’s a troll chasing a gnome maiden, what will you do? On the downer, if you tried something less than obvious for a change (let me trip the gnome and feed her to the troll), then you were screwed.

Unspoken rule: “Good players don’t mess with the GMs pre-planned schedule of encounters”. Another unspoken rule: “Bad players die first”. Planning boiled down to a single question: “What the GM wants our PCs to do next?”

Alex, I wonder if you came from a background like mine.

GM: You see that the wolf’s fur is matted and mangy, clinging to ribs which jut out through scrawny skin. There’s a nasty cut along its flank. It snarls menacingly at you. What do you do?

players: Attack! 🙂

(lots of rolls later)

GM: …so the wolf feasts on your warm bodies. THE END.

playerAlice: You, killer! You railroaded us into a fight we possibly couldn’t win! 🙁

GM: But it was your choice. You could have tried offering it some food, you could have tried climbing a tree, you could have tried retreating to the cabin… 😐

playerBob: Oh, so you tell us NOW? What a jerk! 🙁

The main problem in this example is not the TPK, but that players lock up on the first reaction that comes to their head (because of their training? see my previous reply). Thus they always will feel railroaded. And specially when things go downhill.

“This is a bad technique. First, because it wastes a ton of prep. (As soon as the players choose Option A, everything the GM preps down the path of Option B becomes irrelevant.)” Yeah, but classical CYOA books and LoneWolf gamebooks are meant to be replay-able. And Fighting-Fantasy gamebooks are meant to be replay-ed many times (you won’t beat a FF gamebook at the first try).

I came to tabletop RPGs coming from gamebooks. Since I lacked the concept of “campaign” -’cause wargames were not in my resumee-, throwaway modules with zero replay value rubbed me the wrong way.

“Second, because the players can render it ALL irrelevant the minute they think of something the GM hasn’t anticipated and go with Option X instead.” Lets sue the writer and ask your money back. If she can’t anticipate what the players will do, she’s not doing her job. Dammit, Jim. You are a customer, not a beta-tester!

@ anonimous: I’m not quite sure who you’re arguing with or what point you’re trying to make. You seem to be agreeing with Justin in one post and then disagreeing with him in the next. But here’s my two cents:

“…classical CYOA books and LoneWolf gamebooks are meant to be replay-able.”

What’s good design for a gamebook is not good design for an RPG module. They’re different things requiring different approaches, and Justin’s point is that writing (or running) an RPG module as if it were a gamebook is foolishness. That doesn’t mean it can’t be done, or *hasn’t* been done, but when it *is* done, the RPG suffers as a result (as you acknowledged in your previous two posts).

The choices in a gamebook are limited not because it’s better that way, but as an unavoidable consequence of the medium. In an RPG, there are a lot *more* options and therefore potentially even *greater* replayability. In Deathtrap Dungeon, you can’t retrace your steps, and we accept that limitation because it’s a gamebook. But if I were playing it as an RPG and the GM told me I couldn’t retrace my steps, I’d object.

@Wyvern: In typical gamebooks, you can reboot the dungeon. In typical modules, you can retrace your steps. Different things, different approaches indeed. (Moreover, combat-based gamebooks play quite different than CYOA books as well.)

What’s good design for a gamebook is not *always* good design for an RPG module. I learned it the hard way, when failing to design my own dungeon crawls.

So yeah, I *mostly* agree with you. But then…

options -> choice -> outcome -> consequences

(You meet a sleeping princess. Options a) kiss her b) kill her. Choice: kill her. [cue dice rolling] Outcome: she’s dead, Jim. Consequences: she was Darth Vader in disguise, once more you saved the day, tada.)

“In an RPG, there are a lot *more* options and therefore potentially even *greater* replayability.” …unless every option lead to the same consequences. Let me insist: *more* options per encounter don’t necessarily imply *broader* consequences.

“You seem to be agreeing with Justin in one post and then disagreeing with him in the next.”

Wivern, you can blame it to my poor mastership of English. I every often miscarriage one world for another.

First post (#18) was specifically adressed @Alex.

Back in my days, I played zero modules written like CYOA. Instead, I played plenty of decision-less, choice-less, joy-less moduless instead. Those moduless looked like fun at first, until I strayed off the path and crashed against the glass wall. (And I wish I’d got a chance of playing CYOA-like modules instead — but those days nobody was doing dungeon-crawls.)

Sad thing is, everybody else but me seemed to be OK with them. I was asking Alex if he comes from the same place than me.

Second (#19) and third (#20) posts are adressed at nobody in special.

Second post is what happens when you take players from a Mirror Maze module and put them into a free-choice module. The poor dudes are so used to dodge the glass walls that they can’t even see a decision point UNLESS THE GM GET OUT OF HIS WAY TO SPELL IT.

I made up the example, but it’s an actitude I met in real play… as early as in my very first game, no less!

This is me advocating for CYOA style – because it’s not enough to give the players freedom of choice, you must keep remembering them that their PCs ARE free. In other words, playing & reading moduless with a pre-generated plot have driven me paranoid as hell. So I’m not longer trusting Game Masters unless they prove that they are not cheating.

Justin’s approach is solid, but it’s not a fool-proof panacea. V.gr. “when you liberate the players to freely respond to the situations you create, you’ll discover that they’ll create new situations for you to respond to”. Either this, or you will ruin the day for everybody. I’ve seen it going both ways.

For example: the worst game I’ve ever played was a game of “In Nomine Satanis”. The GM trusted the PCs a mission and left us the players to our own advices. “Ok, somebody knows how do you corrupt a soul? … Guys? … We’re sooo…” [cue two hours of utter boredom] “…ooo screwed!”

For example: the best game I’ve ever played was a game of “In Nomine Satanis”. The GM trusted the PCs a mission and left us the players to our own advices. “Ok, somebody knows how do you rob a bank?” And then one of the players happened to be Danny Ocean in disguise. “We should start by scouting the terrain. Let’s examine entries and exits. Let’s watch for guards and security cameras. We’ll need a distraction.” And the story wrote itself.

“In mystery scenarios, encourage the players to review the evidence that they have. (Although you have to be careful here; you can fall into a similar trap by preferentially focusing their attention on certain pieces of information. It’s really important, in my experience, for players in mystery scenarios to draw their own conclusions instead of feeling as if solutions are being handed to them.)”

I still struggle with this as a GM, particularly in mysteries that span multiple sessions. Two weeks pass and by that time the players have forgotten almost everything they discovered last time. Asking them to review, with no attempt on my part to narrow their focus, yields maybe a 20% recall even with the combined memory of four people.

This is less a problem with scene clues than concept clues. If they remember what they were planning to do at the end of last session, they naturally ask themselves what lead them to that course of action, and that provides a memory aid. Concept clues are more difficult. They require a complex deductive leap, beyond a simple and straightforward recognition that “If you go here, you can get more information”. The result is that my players have a tendency to cycle back and forth through locations and NPC’s without feeling any closer to a solution.

I’ve experimented with some fixes, although none have worked perfectly or without some uncomfortable compromises:

I hesitantly asked them to start taking notes, but that made scenarios feel like a lecture series and negatively impacted their engagement (it’s hard to feel present in a scene when you’re just frantically scribbling).

More successfully, I’ve adapted the Idea Check mechanic from Call of Cthulhu. Discover a clue, make an Intelligence check, recall an earlier detail that connects. I did this with MUCH trepidation, since it inherently veers into the GM hinting at what’s significant. There’s no way to avoid that metadata entirely, except by calling for fake Idea Checks. That would probably be an unmitigated disaster, for the same reason any Red Herring is a disaster.

Another justification is that their characters would remember clues more easily, because they experienced these things with five senses, not through narration. They likely have notebooks, and may keep the evidence at hand. It thus makes sense to offer the players access to character expertise when recalling information, while bypassing the note taking tedium those characters endure.

(. . . and in practice this compromise already occurs in other ways. Nobody makes handouts that have nothing to do with the mystery. If you give the players a love letter stained with blood, they will focus on it far more than if you just told them about it. Being tangible, they are also guaranteed not to forget it.)

To try and mitigate hinting and stay on the right side of player agency, I limit this mechanic to simply reminding them of what they already found; they must do any further extrapolating themselves. I’ve found that in practice, simply calling for Idea Checks at the right time spurs them into reviewing the evidence. It becomes a more tangible and organically narrowed “review your evidence, in light of X”. Then player expertise trumps character expertise, they recall the right information, and make the connection themselves.

On the subject of Socratic questioning, I do wonder if it would be worth facilitating their evidence reviews in a more active manner (“What did you find in the bedroom? What did you find in the woodshed out back? If you were this person, why would you have both these things?”). Unfortunately, I think leading questions like that would just be too much.

[My previous handle was Gamosopher.]

@Jin_Cardassian. Wow, I have basically the same problem with my players. They are great in many ways, but they very often forget crucial bits of information between games. I rarely remind them, but it’s a pretty big problem because all my adventure have some form of “mystery” in them.

I one adventure, they saved a girl that joined a cult but wanted out. She said the cult was trying to summon a evil creature downstair, and that the evil priest is still working on it right now. During the session, the players found the way there, and said “cool, we’ll go look next time”. Next session, they say “ok, let’s go back to the town with the girl. That’s what we were hired to do”, not specifically saying that they don’t want to go look downstair anymore. I did not remind them, so the actual ritual went on, and the evil god was eventually summoned in this world. Did they simply forget? At the end of the campaign, I asked them, but their memories of the adventure was too blurry, so we’ll never know.

In another adventure, they were chasing another cult that succeeded an evil ritual (I might need to reinvent myself…). They intercept the group fleeing towards the town, and find a journal on the leader describing how to invert harmless magic rituals. Next session, they find the place where the actual ritual took place, with tablets with harmless rituals lying around. They completely forgot about the journal. Since it was so directly connected, I reminded them about the content. Did I overstep my bounds? I don’t think so.

I might need to be explicit with my “clues” : maybe I’m much more vague than I think I am. One player started to take more notes, so I guess that also will help. Fingers crossed. The idea about the “idea check” is a neat one, but I fear it would discourage actual thinking/note taking on the part of the players : if the GM let our PC remember vital piece of information through a dice roll, trying to actually remember them and piecing them together become much less important. I might still try this in the future, so thanks!

@Jordan

The feels. I once had a player discover that a circle of stone monoliths was used by a prehuman civilization to commune with Hastur, “whose visage corrodes the illusions that cohere the self”. 30 minutes later, someone kicks a murderous cultist into the circle, triggering the effect. Everyone has a round to get out of there. That player decides to gaze into the dimensional portal as it opens. Needless to say they fail their SAN check and the 1D100 SAN loss takes them out.

I figured that player did it because their character was an inquisitive physicist who just had to know, and they wanted to give them a dramatic death. After the session, I asked them. Turns out they just forgot the whole “looking at Great Old Ones rots your brain” thing that their character had learned 30 MINUTES PRIOR.

Like I say, I was hesitant about the Idea Checks at first, but they were well received. I think it is safe to assume that investigative characters carry around notepads and do lots of tedious accounting to help their memory. Some are lax about it (even if their players are studious), while others are Rustin Cohle (even if the player is Barney Fife). I wouldn’t want to make my players roleplay that drudge work to get the benefit, just like I wouldn’t force them to clean a real firearm before venturing into danger, even though their characters presumably do that too.

So I don’t think Idea Checks are fundamentally different than any other form of character expertise, as long as they don’t make player choice obsolete. That’s why I limit them to memory and NOT deduction. And as always, player expertise can trump a failed Idea Check.

The metadata of only asking them to remember some things but not others does bias their focus, and that’s definitely a problem. I think if you can find a way to obscure the metadata that doesn’t involve Red Herrings, then you’re golden.

Thinking about this problem brought me back to one of Justin’s other articles:

https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/40318/roleplaying-games/rulings-in-practice-perception-type-tests-part-2-the-perception-tapestry

I think Idea Checks can be viewed through a similar lens:

EXTRANEOUS TESTS: Call for fake Idea Checks, and tell them they recall nothing on success. This makes it more difficult for them to know if there is really something to significant to recall when they fail.

REFOCUSING THE TABLE: In practice I’ve found that simply calling for Idea Checks causes players to pay attention, think back to what they’ve found, and make the connection to old information without having to roll.

INNOCUOUS TESTS: Have them recall bits of information that are true (not Red Herrings), but not actual clues. Imagine the players talk to the peasant girl Delphine about people going missing in the woods, and she lets slide that her mother likes to make rabbit stew as a comfort food in trying times. Three sessions later they see an older woman buying rabbits in the market. Call for an Idea Check to recall Delphine’s words. This won’t derail the mystery, but it will obscure the details that ARE significant. It will also build depth into your descriptions by linking new scenes back to past ones.

SPLIT GROUPS: Which group really encountered something significant? If both groups succeed and recall two details, which is the important one? Are either of them important?

@Jin_Cardassian The feels are reciprocal! And thanks, I’ll keep your ideas in mind.

As to the the general topic, I generally agree that presenting a “menu of options” is the wrong approach and that it’s more satisfying to players if they can invent their own solutions.

In my own experience, there are some edge cases that seem particularly prone to frustrate players, and these make the application of free choice more difficult:

1) Not knowing that a type of goal is even possible. Sometimes, if you’re playing in a setting with magic or sci-fi tech, players that aren’t familiar with the tropes may not recognize that hacking/scrying/whatever is even an option. Sometimes it’s the more mundane stuff: detectives not knowing they can work their contacts down at the precinct, or not knowing they can lift a fingerprint, because the players’ knowledge of investigative procedures ends at fedoras and chain smoking.

It’s difficult to simply point out “You have the capacity to do thing X” without also implying “. . . and I, the GM, am saying this because it is a good idea”.

2) Actions which should be self-evident to their characters, aren’t to the players. So the archeologist finds a weird octopus statue. They can’t identify it from sight, don’t realize that they could fix that with research, and never do.

Again, it’s tricky to follow that failed check with “You’d have to research to learn more” without also implying “. . . and I, the GM, am saying that this the logical course of action you should take”.

These problems won’t necessarily be resolved with more time, because the problem is that the players’ grasp of the possibility space excludes certain goals along with means. They can’t ask questions about how to achieve a goal when they don’t have the context to even consider that goal.

You can expand that possibility space by having NPC’s take those actions, but that assumes symmetry between them and the protagonists. It won’t work so well in a superhero setting, for example.

You can have the players make Knowledge checks to figure out courses of action, but I find such mechanical interjections unsatisfying for the same reasons as the GM prompting.

Vivid descriptions can help to a degree (Really highlight the circumstantial evidence of fingerprints in a murder scene / “You recall seeing statues like this in an obscure German archeological journal”). When you deny yourself the ability to prompt players with suggestions, it forces you to structure information in a way that makes these options more evident. But you can only stretch this so far before it becomes an information overload, leading to the other kind of indecisiveness.

This is an excellent article that feels particularly relevant to SpaceBattles and Sufficient Velocity “quests”, a combination of a web serial, a tabletop RPG, and a forum game.

The basic mechanics of the text quest are the Quest Master, who has the roles of the GM alongside those of the writer / author, and the voters, who usually play the game by choosing a course of action via majority vote. Most quests center on a single character or an organization such as an empire or gang, and the voters’ decision is then written up into a update in the thread by the QM. Most of the time the voters have a decision to make, the QM adds a set of default options along with a “write-in” option which voters can fill in to submit their own custom option for consideration by the whole group.

Given that the QM has not just the GM’s ordinary TTRPG authority but also is doing the detailed work of writing everything up into the text, the QM’s offered options have even greater power over their players’ decisions than that of most GMs. Most of the time voters will use the QM’s provided options whole, and voter ingenuity is often limited to remixing or combining or modifying the offered options rather than creating whole write-ins (assuming the QM has seen fit to allow write-ins at all). This common practice greatly compromises the level of agency and investment that voters have in quests.

Voters also often exhibit the stifled initiative you have noted in your other articles about how railroading impacts player behavior. When a quest that usually offers some default options offers a write-in only choice, it’s often several hours before any voter works up the courage or idea to say something (and often it’s a plea to some other, more active and highly regarded voter to come up with something that they will vote on). Voter turnout on one quest I participate in plummets from the ordinary 100+ on decisions with predefined options to less than twenty whenever the QM offers a write-in only decision.

The above segues into a concern I have with implementing this in the context of questing: the combination of the pre-existing voter initiative-stifling culture along with structural majority vote, scattered timezones, and lack of personal or face-projecting virtual interaction may make it hard to draw voters into developing their own options to choose rather than opting to choose from many of the other quests that require less effort to work with. Quests with default options often see voters submitting their votes immediately after they read through an update, while many of those same voters if not given a default option will just read through the update and not come back to vote once someone has developed a write-in option.

The majority vote, scattered timezones, and forum game nature of the quest also play into this because they limit when and how quickly a text quest on Space Battles or Sufficient Velocity can update without losing voter interest. My understanding (having never played a conventional one myself) is that TTRPGs often involve a conversation between the GM and the players which provides both with information and also allows the players to make simple and quick decisions that the GM can immediately adjudicate with a single line or roll. But if a quest holds votes and updates more often than once a day, often some voters will not be able to participate in the vote owing to other obligations and will often leave or choose not to engage at all. And if the quest updates in chunks smaller than 1,000 words, it often loses voters who have been trained to expect or just prefer larger updates at a slower pace. Allowing individual voters to push the player entity to take action often shifts power to those who are awake at the same time the QM is posting, but holding frequent and short votes often alienates voters as well. The sporadic nature of voting also makes it hard to integrate detailed voter plans (i.e. a major part of voter creativity and ingenuity) into the text, as the QM-as-writer will have to implement them into updates while having to consult many different voices who have often have different, contradictory interpretations of the same option that they voted for.

One option I’ve been pondering as a compromise would be to have NPC allies and companions offer their own, in-character and in-universe thoughts on what should be done. Many player entities in quests are the leaders of groups such as adventurer parties or empires with a coterie advisors and companions to help them, but most have at least one long-term retainer or follower that they acquire on their journey. The issue is that this could easily turn into a case of having a “QMPC” that effectively acts as the power behind the PC, with the fourth wall as a thin veil protecting the voter’s decision-making from the QM’s overwhelming power. This problem doesn’t really go away if there are more companions, as they would still be mouth-pieces that present the QM’s options to the voters rather than having the voters create their own.

At the same time, I’m just worried that it might be expecting too much to have voters engage with a quest given the emotionally distant nature of text-based forums, the divergent time-zones of the voter-base, and the many quests that give easy options that allow for lower levels of engagement. Any ideas on how one might overcome these issues and allow voters to have greater agency without scaring them away?

I’M JUST DRIVEN CRAZY BY PLAYERS WHO DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO I DON’T KNOW WHAT’S WRONG BUT IT WON’T CHANGE.

The thing I thought of was this:

PLayers aren’t in the world. They don’t have the experience of the character’s life. And to someone with no experience, freedom is just no choice because they can’t leverage the information.

The agency to make choices comes with understanding choices beforehand.

Or maybe I’m talking about perceptions that are nondirect. They know what other people do, or what they’ve learned in the past. They know what will likely happen if they do these things. And with this material, they have enough recources to get creative, like lego blocks. They can’t get creative if they don’t have something to bump off of. Especially when they’re knew.

If they just follow any choice, it’s not the problem of providing choices but their own willingness to think, but THEN taking away the baby weels would force them to walk, not throwing a toddler to the ground.

“Okay guys, sounds like you’re planning a heist, are you? Your mentor told you the way to do it. You ask questions, you scout the site, you bribe and trick and control people, and then you plan the route and get the stuff, and get in before changes ruin your efforts or people start to suspect you. There are the sneaky ways, the tough ways, or you can play smart and make people do it for you. And he said if you forgot any word one more time he’d open your skull with a skewer to see if there’s a brain inside.”

Typing this I noticed I wouldn’t want to do this if the players haven’t got a goal. But I definitely want to give them this little tutoral. Like the annoying voice of a teacher drilling basics in. We hear them in our head in real life, I can justify it being there to myself.

It works like this: when we makes decisions, we discuss with others, we ask proffessionals. And the only other real person in the world is the gm.

Or maybe I would just persoanlly want this as a player, it makes me feel more in character, and gives me some mind candy to play with. That’s what playing a different people means, doesn’t it?

People get creative with more information, not less, and descriptions only work when people know what to do with them.

Maybe I’m mistaking tutorals for beginners and guiding every choice, but there’s always a fine line there.

Every KP who claims to present situations, which I have played with, ran games that gave me a sick experience. It’s just like the kp refused to cooperate in a conversation and looked on coldly to jibe on why you guys just don’t notice anything. This is probably a biased comment though…… And I would do anything not to give that kind of experience.

(#25) Jin_Cardassian says:

… I hesitantly asked them to start taking notes, but that made scenarios feel like a lecture series and negatively …

From Covid we play over Skype, and we record our sessions there, so it can be downloaded and re-viewed for like a month (and downloaded then stays forever).

I also started our private wiki, where we put all important places, misions/runs/tasks, contacts, NPCs, maps, … at least as name, some fast info/description, maybe link to googlemaps (the house looks like this) and such.

Also my wife (= one of players) started to write some shortened versions of our sessions there, so other players and I can re-read what we basicaly was doing so far. (Using the Skype recordings, so she listen for some time and then write something like “We went to the house, sneaked inside and stunned 3 cultist, before we found the girl on second floor”.) So this is summarry from point of view of one of players (well every player can write there, but there is not much of such activities. But usually they read it in between.)

(#26) Jordan/Gamosopher

… “cool, we’ll go look next time”. Next session …

I usually on start of every session provide some summary, what was so far … like: