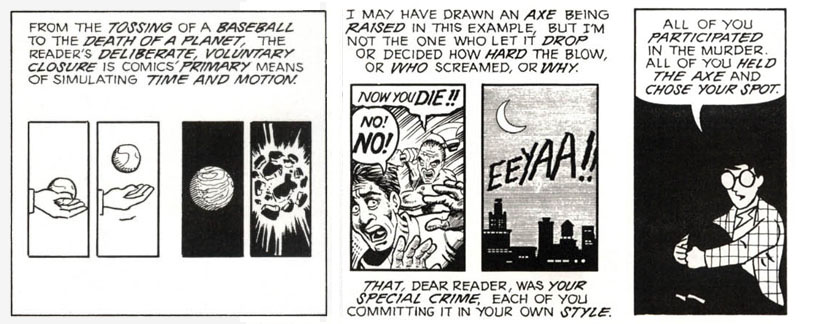

Node-Based Scenario Design describes an ultra-flexible structure for designing scenarios based primarily around the acquisition and flow of knowledge: When the PCs learn about a node, they can go to that node and, usually, find information that will let them learn about more nodes (which they can then go to and find more information).

The structure is extensible, very robust, and lends itself naturally to mystery scenarios, which are based around the acquisition of knowledge – i.e., the information you gain in a node comes in the form of clues (or leads) that point to other nodes where you can continue the investigation. However, GMs who use node-based scenario design often find its usefulness extends far beyond simply traditional mystery stories, as it turns out that the basic concept of “things which are connected to each other” has a fairly broad application.

The original essay included some simple examples of how node-based scenario design works (most notably the Las Vegas CTU scenario in Part 3 of the series), but those really only scratched the surface of what you can do with the structure. Plus, I’ve spent another ten years learning new tricks and techniques. So now it’s time for a little applied theory as we dive into some examples of how the node-based structure can be used in actual practice.

REALLY PRACTICAL EXAMPLES

If you just want to see full scenarios featuring node-based scenario design, here’s a quick reading list.

The Masks of Nyalathotep is a classic Call of Cthulhu campaign by Larry DiTillio & Lynn Willis. It had a major influence on codifying the Three Clue Rule and is also a great ante-example of node-based scenario design at a campaign-wide level.

Eternal Lies by  Will Hindmarch, Jeff Tidball, and Jeremy Keller is a Trail of Cthulhu campaign inspired by The Masks of Nyalarthotep. I did an Alexandrian Remix of the campaign, which is probably one of the most comprehensive examples of how I prep a node-based campaign currently available.

Will Hindmarch, Jeff Tidball, and Jeremy Keller is a Trail of Cthulhu campaign inspired by The Masks of Nyalarthotep. I did an Alexandrian Remix of the campaign, which is probably one of the most comprehensive examples of how I prep a node-based campaign currently available.

Quantronic Heat is a three-part adventure series for the Infinity Roleplaying Game designed by Nick Bate and myself (mostly Nick). The first adventure, “Conception,” in particular, is a very clean example of scenario-level node-based design.

Here on the Alexandrian, you can check out The Strange: Violet Spiral Gambit. This is another very clean example of scenario-level node-based design, serving as a pretty good Platonic ideal of what a node-based mystery scenario looks like. Other examples on the site include Gamma World: The Egyptian Incursion, Star Wars: Red Peace, and Eclipse Phase: Psi-chosis.

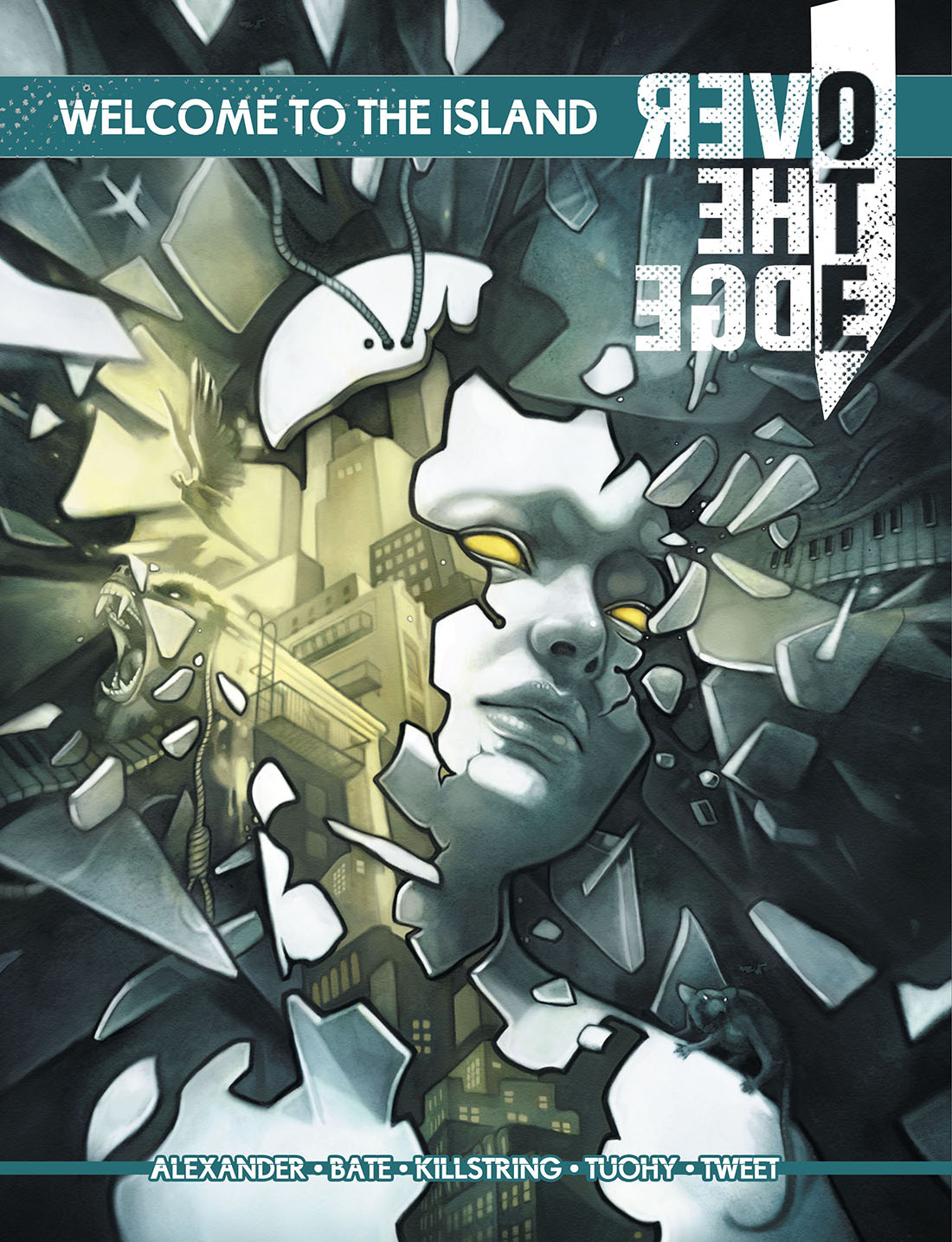

Welcome to the Island is an adventure anthology for Over the Edge that I was lead developer for. The scenario I co-wrote for the book (“Seversen’s Mysterious Estate,” with Jonathan Tweet) isn’t node-based (it uses the party-planning scenario structure), but most of the other scenarios in the book do use node-based design, often adulterated with other scenario structures. For example, Jeremy Tuohy’s “Battle of the Bands” has the PCs trying to reunite a pop-punk band from the mid-2000s, with each band member being a node that they need to track down.

NODES VS. REVELATION LISTS

What is a node?

In Part 9 of Node-Based Scenario Design I list five types of nodes:

- Locations

- Characters

- Organizations

- Events

- Activities

Activities have proven to be exceedingly rare in my scenario design (maybe your mileage will vary). In any case, I tend to think of nodes as things that the PCs can go and interact with.

PROACTIVE NODES

There are also proactive nodes which typically do the opposite: They come to the PCs and interact with them.

Proactive nodes are usually characters. I often think of them as the “response teams” of a scenario. This is frequently literal, with my proactive nodes being the people who are sent to deal with the PCs once the bad guys realize they’re snooping around. But it’s also a useful metaphor: Proactive nodes are the easiest tools I can use as the GM to take action at the table instead of simply reacting.

What about other proactive nodes?

Well, locations tend to be stationary and rarely follow people around… unless you apply sufficiently advanced technology and/or magic. The technology doesn’t really need to be all that advanced, either: An abandoned ghost ship drifting into the town’s harbor can easily be a proactive node.

Organizations can be proactive in their responses, but the response usually takes the form of a specific response team (which would usually be the actual, character-based proactive node).

Events can be proactive if they’re of a sufficiently large scale or if they’re specifically targeted at the PCs: A city-wide festival or a ritual that causes all the trees in the forest to start weeping blood count as the former. A series of enigmatic phone calls that ring up a PC’s cellphone would be an example of the latter.

Almost anything can be a proactive node if it can be framed as information being pushed on the PCs. For example, if the PCs are cops investigating a series of bank robberies, they would be automatically notified if a new bank robbery took place. (Is this an event or a location? Both? Does it matter? Don’t get too obsessed with the categories here.)

In addition to creating a living world where there are both long-term and short-term reactions to the PCs’ choices, proactive nodes also have the practical function of getting a scenario back on track. For example, if the PCs have missed all the clues pointing to a particular revelation, a proactive node can be used to provide a fresh lead.

REVELATION LISTS

On that note, a revelation is any conclusion that the PCs can make or need to make in the scenario (see the Three Clue Rule and Using Revelation Lists for more information).

A revelation can be a node (i.e., “we need to go check out that location / character / organization / event”), but it can also be stuff that isn’t a node (i.e., “the runes are Achaean” or “the rage-wraiths can be kept at bay by the smoke of burning wisteria”).

In my more recent work, I’ve started talking about evidence & leads, where leads point you to places where you can continue investigating (i.e., new nodes) and evidence points to other types of revelations (often the solution to the mystery; e.g., Bob’s the killer). In practice, though, these can often overlap. “Bob’s the killer” is a mystery solution which also points at Bob (who, as a character, might be thought of as a node). Furthermore, for a satisfying mystery you’d probably want to establish Bob before revealing he’s a killer, so there’s a “Bob exists / is here / is involved” revelation that points to Bob-as-a-node and then a “Bob did it” revelation that points to the Bob-as-solution.

I think it’s useful to separate the node-based list of revelations from the list of other revelations. I just find this to be conceptually clearer. (This assumes that there ARE non-node revelations. That won’t always be the case. Pure procedurals and breadcrumb-style mysteries often have a 100% overlap between revelations and nodes. This also tends to be true for non-mystery scenarios.)

In any case, your node list will most often be simply copy-pasted into your revelation list, with a couple notable exceptions:

The initial node that begins a scenario almost never requires a revelation list. The exception are scenarios with multiple points of entry, in which case you may want the investigation from one entry node to potentially lead to other entry nodes. (This is also only true within the context of the scenario itself: The PCs might actually be led to the initial node of a scenario by the revelation list of another scenario. More on that when we discuss fractal nodes and node-based campaigns below.)

Proactive nodes usually don’t have a revelation list, either. These nodes are designed to come looking for the PCs, after all, so they don’t necessarily require a mechanism that will lead the PCs to them. (Many nodes, of course, could be both. I tend to just list those as normal nodes and then opportunistically play them as proactive when or if it comes up.) What I will do for proactive nodes, though, is include a list of them in my prep notes with the likely triggers that will cause them to take action and/or become available for action. These triggers can include stuff like:

- Monitoring Avery Hall [and might therefore spot the PCs investigating Avery]

- Sent to kill Avery Hall [potentially while the PCs are talking to Avery]

- Staking out Node 1, Node 2, or Node 6

- Notified by Avery [if she becomes aware of the PCs]

- Sent by Avery if she learns they know about the jade statue

- Trigger randomly as the PCs are traveling between locations

- Respond to any violence in the neighborhood in 1d6+10 minutes

These triggers aren’t really a binding list. They’re more of a quick personal reminder for how particular tools can be used.

Go to Part 2: Node-Based Campaigns

THE SECRET LIFE OF NODES

Part 1: Secret Life of Nodes

Part 2: Node-Based Campaigns

Part 3: Fractal Nodes

Part 4: Nodes Aren’t Everything

Part 5: Naturalistic Node Design