Many people are familiar with the 5 Room Dungeon. It’s a simple little structure that you can very quickly pour content into, allowing you to create simple dungeon scenarios on the fly. Basically you design a dungeon with 5 rooms, and in those rooms you place:

- Room 1: Entrance And Guardian

- Room 2: Puzzle Or Roleplaying Challenge

- Room 3: Red Herring

- Room 4: Climax, Big Battle Or Conflict

- Room 5: Plot Twist

Depending on the system you’re using and exactly what you stock each room with, this should produce about 2-4 hours of game play.

Personally, I’m not a huge fan of the 5 Room Dungeon: Partially because its structure is too rigid (which results in effective material, but also very predictable material if you use it too frequently). And partially because a remarkable number of people preach it as the one-true-way of dungeon design (which isn’t really the fault of the structure itself, but combines rather horribly with the first problem).

But what the 5 Room Dungeon does a very good job of demonstrating is how valuable it can be to have a simple structure like this in your back pocket. Not only does it let you very quickly (and very effectively) prep simple scenarios, it’s also incredibly useful when you need to start improvising during a session: You can very quickly brainstorm ideas, paste them into the proven scenario structure, and know that the result is, on a basic level, going to work.

I’ve got a similar structure that I default to whenever I’m looking to whip up something simple and quick. I’ve come to call it…

THE 5 NODE MYSTERY

The 5 Node Mystery structure arose pretty much completely independently from the 5 Room Dungeon, but the repetition of the number 5 isn’t really coincidence: Five good, meaty chunks of interactive material is pretty much what you need to fill an evening of gaming. The interaction between five different elements is also roughly the bare minimum complexity required to create something more meaningful than a solitary random encounter. Nothing wrong with a random encounter, of course, but if you’re looking for the next step up — if, for example, you’re interested in what the random encounter might lead to — then this is basically what you’re looking for.

You use the 5 Node Mystery when you want a simple, fairly straight-forward investigation. It uses node-based scenario design and it works like this:

1. Figure out what the mystery is about. Was someone murdered? Was something stolen? Who did it? Why did they do it?

2. What’s the hook? How do the PCs become aware that there’s a mystery to be solved? If it’s a crime, this will usually be the scene of the crime. It could also be “place where weird shit is happening”. Or maybe someone or something comes to the PCs and brings the mystery with them. (Thugs kicking down the door is a classic.)

3. What’s the conclusion? Where do they learn the ultimate answers and/or get into a big fight with the bad guy? (Big fights with bad guys are a really easy way to manufacture a satisfying conclusion.) This will be your Node E.

4. Brainstorm three cool locations or people related to the mystery. Ex-wife of the bad guy? Drug den filled with werewolves? Stone circle that serves as a teleport gate? These will be your Nodes B, C, and D. (Hint: Brainstorm more than three items. Then pick the three coolest ideas. You’ll end up with better stuff. Also: Before you toss the other ideas, see if there’s any way that you can combine them with the three you picked and make them even cooler.)

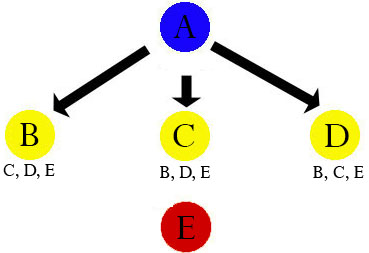

5. You’ve got five nodes. Connect ’em with clues. The default structure looks like this:

The basic idea here is that Node A points you in three different directions (although, remember, the PCs might find only one of the clues). Then those three locations point to each other and also point towards the big conclusion. Simple.

You’ll also find that the precise structure of the 5 Node Mystery is easy to modify on the fly. In some cases, you’ll find that the nature of the scenario will pretty much dictate the pattern of the clues. (For example, while working on the Violet Spiral Gambit — which was designed in a few hours using this structure — I discovered that it made more sense for the initial node to point to two locations and then have those two locations point to a third. Then I loaded up that third location with a bunch of different clues all pointing to the conclusion.) About the only thing you should avoid as a general rule are clues pointing directly from Node A to your conclusion.

There is a possibility in this structure, of course, for the PCs to go from Node A to Node B to Node E (skipping Nodes C and D). In some cases, the scenario will be modular enough that this just means the conclusion isn’t what you thought it was. (You thought the conclusion was a big showdown with a bad guy in the violet tower at the center of the graveyard. Turns out, it was actually a rooftop chase as the badly injured PCs try to escape the werewolves from the drug den.) In other cases, the nodes left behind the PCs will metastasize into new adventures — either because the werewolves end up causing trouble or because when the PCs go back to mop-up the werewolves they’ll find clues pointing them to other scenarios.

THE 5 x 5 NODE CAMPAIGN

Seasoning your scenario with clues pointing to other scenarios is actually a pretty good way to start expanding from 5 Node Mysteries into designing more interwoven campaigns.

1. Design five 5 Node Mysteries. You might have some idea about how they all relate to each other as you’re designing them, but maybe not. Discovering how seemingly unrelated things are actually connected to each other is a great way to make both things richer and more interesting.

2. Arrange the 5 Mysteries into the same node pattern. In other words, Mystery A will have clues pointing to Mysteries B, C, and D. Mystery B will have clues pointing to Mysteries C, D, and E. And so forth. (If you didn’t already know how the mysteries related to each other, the process of figuring out how clues for Mystery D ended up over in Mystery B is the part where you’re going to figure that out.)

As you’re seeding your clues into each mystery, mix it up a bit. Some clues will be the “pay-off” for solving the first mystery: You’ve taken out El Pajarero, but who was he really working for?! But don’t fall into the trap of always putting the clues in the concluding node. Spread ’em around a bit.

And that’s basically it. It’s a very simple technique for you to use, but you’ll find that (much like the technique of the second track) it creates experiences for your players which are complicated, interesting, and ornate.

FURTHER READING

Game Structures

Node-Based Scenario Design

Gamemastery 101

I’ve been reading through all of this again, and just found this entry into the canon, as it were. (I first ran across your “Three Clue Rule” years ago, when I was looking for advice on how to run Masks of Nyarlathotep after a 20 year hiatus…) Another excellent idea here.

What I’d really like to see you do though, is publish this whole series, from Game Mastery 101, the different kinds of ‘crawl, scenario design, etc., all the way on through, in one place. It would be a tour de force.

I just came across this article — http://www.critical-hits.com/blog/2009/06/02/the-5×5-method/ — and I thought I remembered you mentioning it, so I did a search that brought me here. It’s not quite the same as your idea, but still an example of great minds thinking alike.

This is brilliant. Just come across this article a few days ago, and been designing my next session around it – so simple. So easy. So much better than my previous session-preps! Can’t wait to run it.

Your posts on node-based scenario design have been immensely instructive to me, thanks a lot. Now I’m wondering, how do you award XP (if running an XP-based system) in a node-based framework?

My issue is that in most D&D editions, the XP system breaks down when running mysteries as there’s just not enough combat for PCs to level up at a satisfying pace. So what I’ve done so far was arbitrarily awarding XP on the fly, when I considered players had done enough relevant stuff.

Now I’m thinking that node-based design may provide an alternative way to distribute XP, in a more structure way. 5E’s Dungeon Master’s Guide, on page 261, mentions “milestones” among alternative XP systems : “When awarding XP, treat a major milestone as a hard encounter and a minor milestone as an easy encounter.” This is what I’ve been doing, albeit in a very unstructured way.

So, what about treating nodes and clues as milestones? As per the DMG (p. 82), there are four encounter difficulties : easy, medium, hard and deadly. In terms of XP, medium, hard and deadly encounters are worth 2, 3 and roughly 4.5 easy encounters respectively. To level up, in mid-levels adventures (levels 5-11), you need to complete about 30 easy encounters, 15 medium encounters, 10 hard ones or 6-7 deadly encounters. At lower levels you need less, which is logical as players aren’t expected to spend too much time there. And, oddly, you need less at higher levels as well. Anyway, let’s focus on the mid-levels range.

Your 5-node structure, which is sort of canonical, contains a total of 12 clues. What if we awarded XP for each clue found and correctly interpreted ? Treating clues as medium encounters, a very thorough and efficient party that gets them all would be close to the next level (12 medium encounters out of 15). Now, what about awarding hard-encounter XP for each node reached by the PCs beyond the first one? Then, our thorough party would have more than enough XP to level up : 12 clues plus 4 nodes equal 12*2+4*3 easy encounters, or 36 easy encounters.

Now, since not all parties are that thorough, I think we may treat nodes as deadly encounters for PCs to have a reasonable chance at levelling up at the end of the mystery. An average party will probably visit two intermediate nodes, as well as the final one, and find at least three clues in the process (by the Three Clue Rule, they find at least one clue in the starting node, and one more in each intermediate node they go to). 3 deadly encounters and three medium ones correspond to 3*4.5+3*2=19.5 easy encounters, so this party would be roughly two-thirds of the way to next level. Adding a (deadly) boss fight takes them even closer, and we may expect them to find a couple more clues along the way. We may also consider awarding half XP for a clue that was found but not correctly interpreted.

And so on. I don’t know if this is going to be balanced but I’m curious to try that out. At higher levels, since less XP is needed to level up, we may downgrade nodes and clues to hard and easy status, respectively. Anyway, I’m just curious to know whether you use a similar system, and what you’d think of it.

[…] starałem się uwzględnić rady ze znakomitego bloga The Alexandrian, w szczególności tego i tego tekstu, a także chęć zapewnienia graczom możliwie dużej swobody […]

[…] While I was creating the scenario, I took into account the advice from the great blog of Justin Alexander, in particular this and this text. […]

Eventually I’m going to comment on all your old posts and say “thank you”, but apparently I haven’t yet. The whole three clue thing was such a great way of thinking about adventures, not only freeform mysteries, but for things like “are there three ways through this locked door in the dungeon” etc, and I’m looking forward to using this for a simple mystery one shot.

[…] The Alexandrian: Five Node Mystery […]

I don’t know how familiar you are (if at all) with Sly Flourish (Mike Shea) but he collaborated with Johnn Four recently and said essentially the same thing you lay out in this article. Here’s the link if you’re interested: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0xYZZoxVY0 The other videos in the series are firewalled behind newsletters subs and Patreon subs, but this first one is freely available. Mike Shea is a big fan of your work, he talks about it a lot and uses similar methods in his “Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master”.

Tried this out, a challenging but fun exercise! Thought I’d share what I did.

Revelation list for “Murder in Eulenmoor”

Astral pond (hook)

Invitation to Eulenmoor mine by two letters requesting: dig deeper! – countess Katrinella and stop mining! – Brewer Bess. At arrival, mine had stopped as mine-king Drolim died yesternight. You join a mourning trail to the swamp where he was found floating.

Who killed dwarf king Drolim?

1) Everyone was at fullmoon party except Drolim and the suspects (Astral pond) :

Vampire Countess Katrinella, Drolim’s Pet Owlbear Hootsie, blond satyr Stixy,

Silverclad Derro Drans, Drolim’s Daughter Norbelda, Witch werewolf Bess, and the troll Zulabar. (a large cast and I did not present them clearly regretfully)

2) hooves at midnight (Zulabar)

3) Drolim’s leg was cut off and was replaced with an illlusion (Astral pond)

Why did Stixy murder Drolim?

1) Drolim’s pet owlbear Hootsie (Avantris <3) killed a goat (Bess, stonefingers)

2) Drolim stole Stixy’s flute (Norbelda, Starmine) flute-bone from the leg (lore)

3) Derro (that Drolim unleashed) popularized strange music (Stixy)

Trihorn tavern and goat rental

1) Drolim’s debt for an injured goat (Owls fighting over his bag at Astral pond)

2) There were hooves and a splash at midnight (Zulabar, hunter, stonefinger lair)

3) Drolim wanted to make better instruments for the satyrs (Norbelda, Starmine)

Stonefingers hill

1) Bess healed the goat Drolim hurt (Trihorn tavern, Stixy)

2) Zulabar's water canals from the murder scene leading here (Astral pond)

3) Drolim was inspired by the star spectacle at finger hill (Drans, mine)

Starmine

1) Drolim found new ore last moon (Astral pond audience, proactive)

x) Loose owlbear! (proactive)

2) Drolim declined to the party yesternight because he was working late (trihorn tavern)

3) Drolim had nightmares since the Derro arrived at the mine (Bess, stonefingers)

Crab lake castle

1) Election of a new mine king (Katrinella, hostess, starmine's galaxy dome)

2) Order for ten litres of forgetfulness potion for burial (Bess, stonefingers hut)

3) Musicians practising for the ceremony (Trihorn tavern)