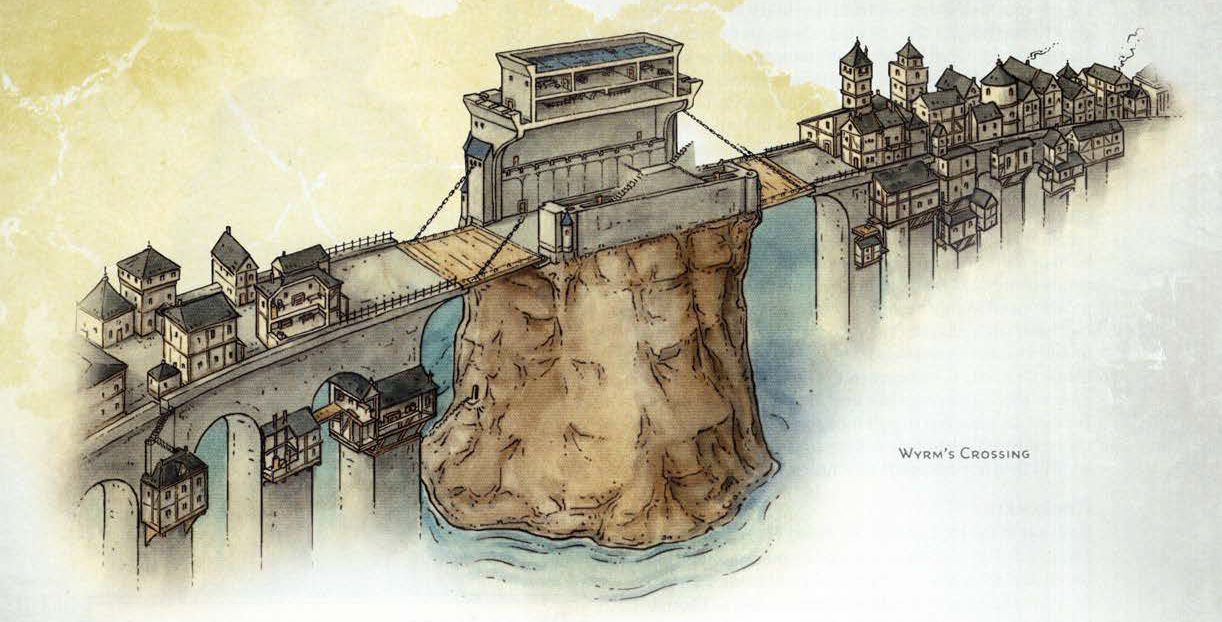

The PCs’ time in Baldur’s Gate is entirely dedicated to investigating the machinations of the Vanthampurs. (You can try to squeeze other stuff in, but there’s not really any space to do it: The PCs are told to investigate the murders by going to the Dungeon of the Dead Three, immediately follow leads from there to Vanthampur Manor, and then immediately follow the leads from the Manor out of town. Realistically speaking, they’ll spend less than 48 hours in the city. Probably significantly less.)

In practice, these investigations are designed to lead to three central revelations:

- The murders ordered by Duke Vanthampur

- The devilish schemes involving the Shield of the Hidden Lord

- The truth of Elturel’s Fall

As written, there are significant problems with all three.

PROBLEM: THE MURDERS

The Vanthampur “plan” to seize power in Baldur’s Gate doesn’t actually make any sense: Duke Vanthampur has hired Dead Three cultists to murder people in order to “shatter confidence in the Flaming Fist” so that the city will stop paying them and they’ll… leave?

First, Baldur’s Gate is already notoriously the murder capital of the Sword Coast and has been for centuries. If “bunch of murders” was going to break public confidence in the Flaming Fist, it feels like it would have happened a long time ago.

(For context, the entire adventure begins in a tavern where everyone goes armed because otherwise you’re likely to get murdered. It’s one of the nicer taverns in town.)

Second, the Flaming Fist is a “mercenary army,” but they’re not just visiting. They’ve been a fundamental institution of power in Baldur’s Gate for more than a hundred years. They’re also the only meaningful military force in town. Historically speaking, when you abruptly stop paying the army, the result is not “they peaceably go away and leave you in charge.”

The result is that the army is now in charge.

Even beyond that, it’s entirely unclear how getting rid of the Flaming Fist is supposed to make Vanthampur the new Grand Duke. The book says that she “has brokered a deal that will enable her to claim the role of grand duke once the Flaming Fist disbands,” but brokered with who exactly? To become grand duke you have to be elected by the Parliament of Peers. Why would any significant portion of the parliament want to disband the Flaming Fist? And if they did, why wouldn’t they just vote to do it?

To sum up: It doesn’t make sense that Vanthampur is trying to do what she’s trying to do, and the way she’s trying to do it will never work.

PROBLEM: SENDING BALDUR’S GATE TO HELL

Duke Vanthampur and/or Thavius Kreeg (it’s a little vague) also have another plan: They’ve stolen the Shield of the Hidden Lord, a powerful magical artifact containing a trapped pit fiend named Gargauth which “fuels the avariace and ambitions of evil-minded folk in Baldur’s Gate.” (The book is inconsistent on whether the pit fiend does this by loquaciously convincing people to do bad things or if it just exudes an aura of evil that ramps up the murder rate citywide.) They’re going to use the Shield to suck Baldur’s Gate to Hell, just like Elturel was!

First, I just want to briefly comment on how bizarrely warped the lore of the Shield of the Hidden Lord has become. In 2nd and 3rd Edition, Gargauth was a demigod; he was the Tenth Lord of Hell who had been cast out by his fellow devils and chose to wander the Prime Material Plane. The Shield of the Hidden Lord first appeared in 3rd Edition, and it was a powerful evil artifact that allowed Gargauth to communicate with and subtly influence its bearer.

Gargauth vanished in 4th Edition, but in 5th Edition he reappeared in Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide as “a mysterious infernal power who seeks godhood while trapped in the world within a magical shield.” Descent Into Avernus then reveals that this is, in fact, the Shield of the Hidden Lord, which is no longer an evil artifact created by Gargauth, but instead a celestial artifact in which Gargauth has been imprisoned.

(I mention this primarily to explain why, when I completely jettison a lot of this lore and replace it with something completely different, I’m not going to feel particularly guilty about it.)

Second, the Companion hung in the sky above Elturel for fifty years before the city could be sucked into Hell, but apparently you can do “much the same thing” (p. 11) with a pit fiend bound inside a celestial shield.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense, and the book’s lack of interest in providing any explanation for how this is supposed to work is really just a symptom of Descent’s lack of a clear vision for the metaphysics and continuity involved in Elturel’s fall.

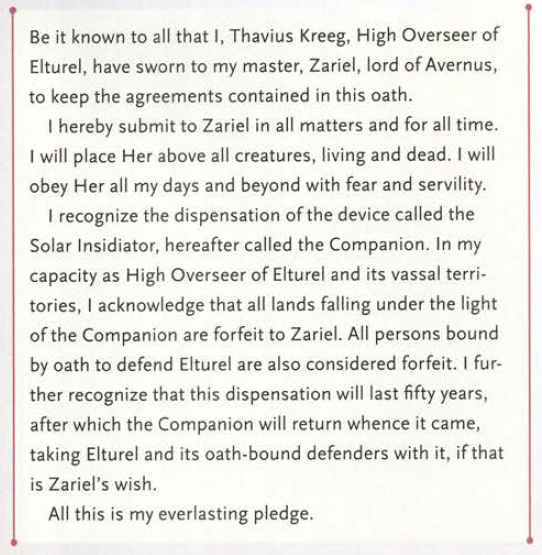

For example, Descent Into Avernus is built around the central concept that High Observer Thavius Kreeg made a deal with devils to create the Companion and, in exchange, he sells the city he rules to the Nine Hells.

The problem is that this cannot possibly be true.

Thavius Kreeg wasn’t High Observer when the Companion was created because:

- The position of High Observer came into existence after the Companion.

- Kreeg wasn’t the first High Observer.

- The Companion was created in order to overthrow the existing (vampire) lord of the city.

The beginning of Descent Into Avernus recognizes the problem and tries to fudge a fix: Kreeg, who was not the ruler of the city, “took credit for summoning the Companion, was hailed as the savior of the city, and rose to become its high overseer.”

By the time the book gets to Candlekeep, however, the writers have forgotten both the original continuity and the continuity described at the beginning of the book: Kreeg is now the ruler of Elturel when he made the deal with Zariel (and before the Companion was created).

On the one hand, this actually makes more sense (because otherwise you’re saying that just any random dude in a city can agree to send it to Hell, which makes it unclear why the devils haven’t scooped up all the cities of Faerun a long time ago), but on the other hand you’ve got a superpositioned continuity glitch in which both of its quantum states have really glaring problems.

(Descent Into Avernus has so little care for actual continuity here, that they somehow changed Kreeg’s title from “High Observer” to “High Overseer” and nobody noticed the error.)

It’s certainly possible to slide some continuity glitches past your players, but this is literally the entire adventure: They have to know how Elturel was damned so that they can figure out how to save it.

PROBLEM: THE TRUTH OF ELTUREL’S FALL

At the end of the Dungeon of the Dead Three, the PCs meet and interrogate Mortlock Vanthampur, who will flat out state the premise of the scenario: “If [my mom] gets her way, Baldur’s Gate will share Elturel’s fate and get dragged down into the Nine Hells.”

This is the first time the PCs will be able to learn this, so they’re going to have some questions. The GM will also have questions (like, how does this NPC know this but his brothers don’t, even though his brothers are explicitly more trusted by their mother? How much does he actually know?), but the adventure isn’t going to be helpful in answering any of them.

What I’m more interested in here is the pacing of major revelations in a campaign: This isn’t how you do it. Don’t just dump the entire solution to a major mystery into the PCs’ laps as an offhand comment in an unrelated conversation.

In Part 1, I talked about how the Mystery of Elturel’s Fate is the central, driving mystery in this first part of the campaign. We can now break this down into five specific phases of revelation:

- Elturel was destroyed

- Elturel was destroyed by devils

- High Observer Kreeg is still alive!

- Kreeg is responsible!

- Elturel wasn’t destroyed, it was actually taken to the Nine Hells.

Once you break it down like this, you can see how each one of these revelations packs a big punch. If you do it right, each one should be a “Holy shit!” moment for your players.

But you can also see how the conversation with Mortlock short-circuits this entire process of discovery, jumping straight to the end. All those big, cool, memorable moments are just thrown away.

Everything else in this chain of revelations is similarly dysfunctional.

For example, instead of the PCs discovering that Kreeg is still alive (shocking twist!), a random NPC they’ve never met before walks up to them in the street and tells them. (It’s almost insulting how pointless this is, by the way: The PCs are literally on their way to a location where they’ll discover Kreeg for themselves when the NPC shows up to steal their thunder.)

Later there’s an infernal puzzlebox that the PCs need to take to Candlekeep and have opened. When they do, they find inside the infernal contract Kreeg signed that doomed Elturel. This should be a mind-blowing revelation of epic proportions…

…except the person who tells them to go to Candlekeep to have the puzzlebox opened literally tells them what’s in the box before they open it. (And then another NPC makes sure to reiterate it immediately before opening it.)

So there’s this big, cool mystery that the entire campaign is framed around. But Descent Into Avernus constantly undercuts the revelation of that mystery and ferociously deprotagonizes the PCs while they “investigate” it.

PROBLEM: THE INVESTIGATION TRACK

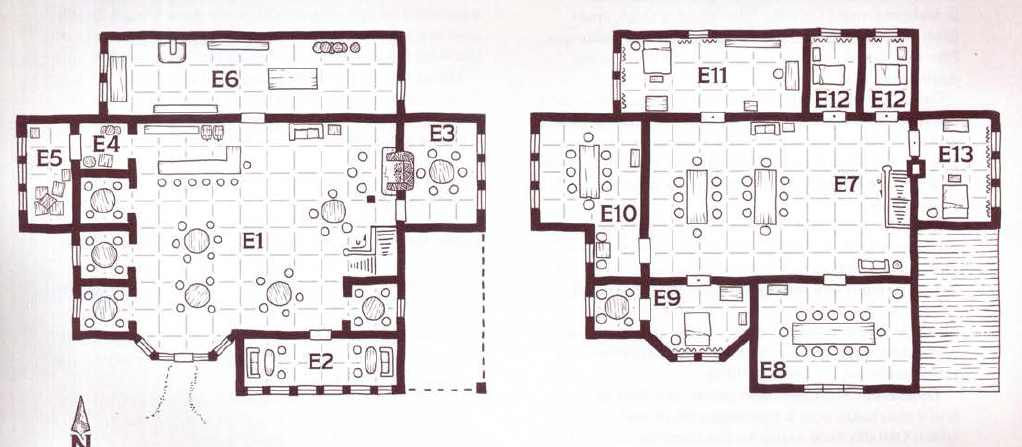

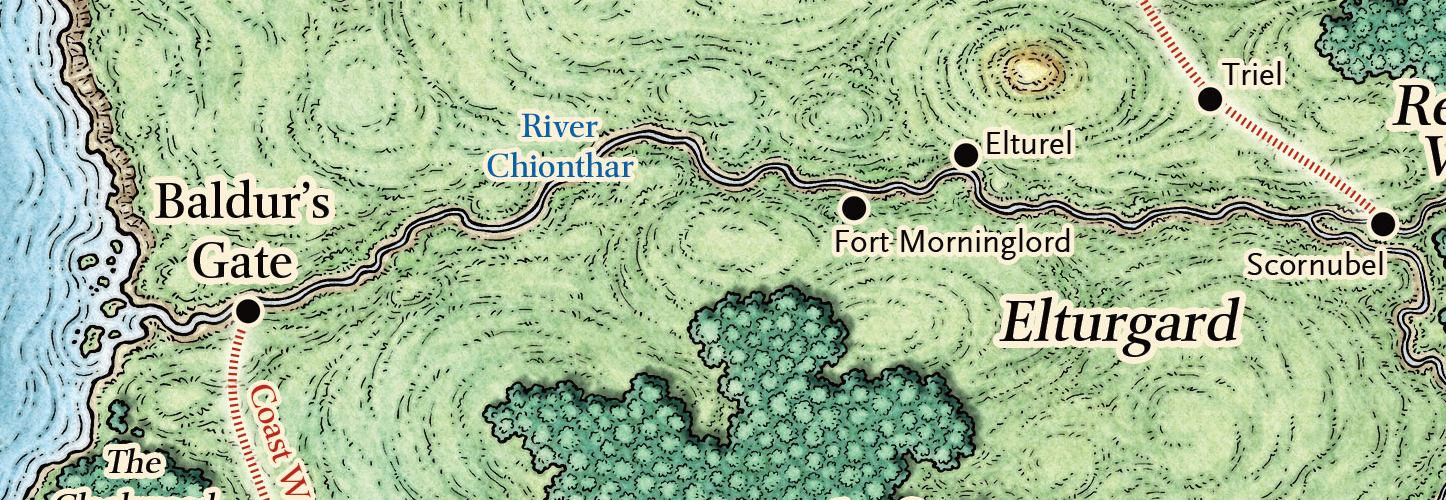

What I’m referring to as the Vanthampur Investigations consists of three nodes:

- Dungeon of the Dead Three

- Amrik Vanthampur @ the Low Lantern

- Vanthampur Manor

These are largely presented as a linear chain in Descent Into Avernus. Unfortunately, this chain is extremely fragile. This is mostly due to Mortlock: The PCs are supposed to find him in the Dungeon of the Dead Three, interrogate him, and basically get all the information they need to proceed.

There are several problems:

First, as we’ll discuss in Part 3F, it’s very easy for the PCs to never find Mortlock.

Second, if they find him, he’s being attacked by another cultist and will be killed if the PCs don’t jump in and save him. (What if they don’t?)

Third, if they do save him, the first thing he’ll say is, “I’m the serial killer you’ve been looking for.” (Odds that the PCs will now kill him without further ado? Pretty high in my experience.)

Fourth, having just confessed to being the serial killer the PCs are here to kill, Mortlock will now say, “Hey, can you help me take revenge on the people who tried to kill me?” (I’m not making this up.)

Fifth, remember that the PCs have been pressganged into a very simple job: Destroy the Dead Three cult. So the last thing Mortlock says is, “If you’ve made it this far, you’ve killed most of the leaders of the Dead Three cult. Without them, the cult will break up.” In other words, “Congratulations! You’re all done! This adventure is 100% complete!”

If you get past all of that, Mortlock tells the PCs what they’re supposed to do next: Kidnap his brother Amrik so that they can use him as leverage while negotiating with his mother.

But negotiating with his mother to do… what?

The adventure doesn’t seem to know. In fact, it promptly forgets the entire idea except to briefly tell the DM later that it definitely won’t work. (“Proud to a fault, [Thalamra] would rather die than surrender or be taken prisoner —and she happily watches any of her sons die before consenting to ransom demands.”)

The failure of the scheme doesn’t bother me. (“Go ahead and kill him,” is a perfectly legitimate moment and builds pretty consistently from her known relationship with her kids.) What bothers me is that there doesn’t seem to BE a scheme. The PCs are told to do a thing, but are given no coherent reason for doing it.

(This is a somewhat consistent problem in the adventure that we’ll discuss at greater length in Part 6.)

REMIXING THE INVESTIGATION

We’re going to largely focus on three things in order to fix the Vanthampur Investigations:

- Revise the lore and backstory so that it makes sense

- Do some minor rehab work on each individual node

- Toss out the current investigation structure and replace it with revamped revelation lists, made robust by applying the Three Clue Rule

Those of you familiar with my work will probably be unsurprised to discover that we’ll also be introducing some node-based scenario design to give the whole thing more flexibility. (There’s only three nodes, of course, so we’re not going to go too crazy here.)