Enemies in Feng Shui — the action movie RPG of fast and furious combat inspired by the classic Hong Kong films of Jackie Chan, John Woo, Tsui Hark, Michelle Yeoh, and Jet Li — are split into four types: Mooks, Featured Foes, Bosses, and Uber-Bosses.

Mooks, in particular, are treated a little differently by the system. First, they’re significantly worse than any other foe in terms of statistics. And, second, they instantly get knocked out of the fight if they get hit. Don’t even bother rolling for damage.

(If you’re thinking, “Hey! That sounds like minions from D&D 4th Edition!” you’re not wrong. They got the idea from Feng Shui.)

The goal is that you can — and should! — stuff your fight scenes full of disposable mooks to create frenetic action and allow the PCs to show off their badassitude. (Even in a baseline fight, you’ll have 3 mooks per PC, and the number only goes up from there. In fact, when you want to make an easier fight, you actually increase the number of mooks, albeit while decreasing the number of featured foes.)

Feng Shui also uses a 1d6 – 1d6 core mechanic, so for every check you’re rolling two d6’s. That means that the GM is going to be rolling a lot of dice to resolve all of their attacks. Despite all that dice rolling, though, it’s quite likely that literally none of those attacks will hit. (They are just mooks, after all.)

If you roll all of those attacks one at a time, this can be a huge drag on gameplay.

One option to avoid this is to roll fistfuls of dice! There’s an article here on the Alexandrian that dives in to a lot of different techniques you can use to make this work.

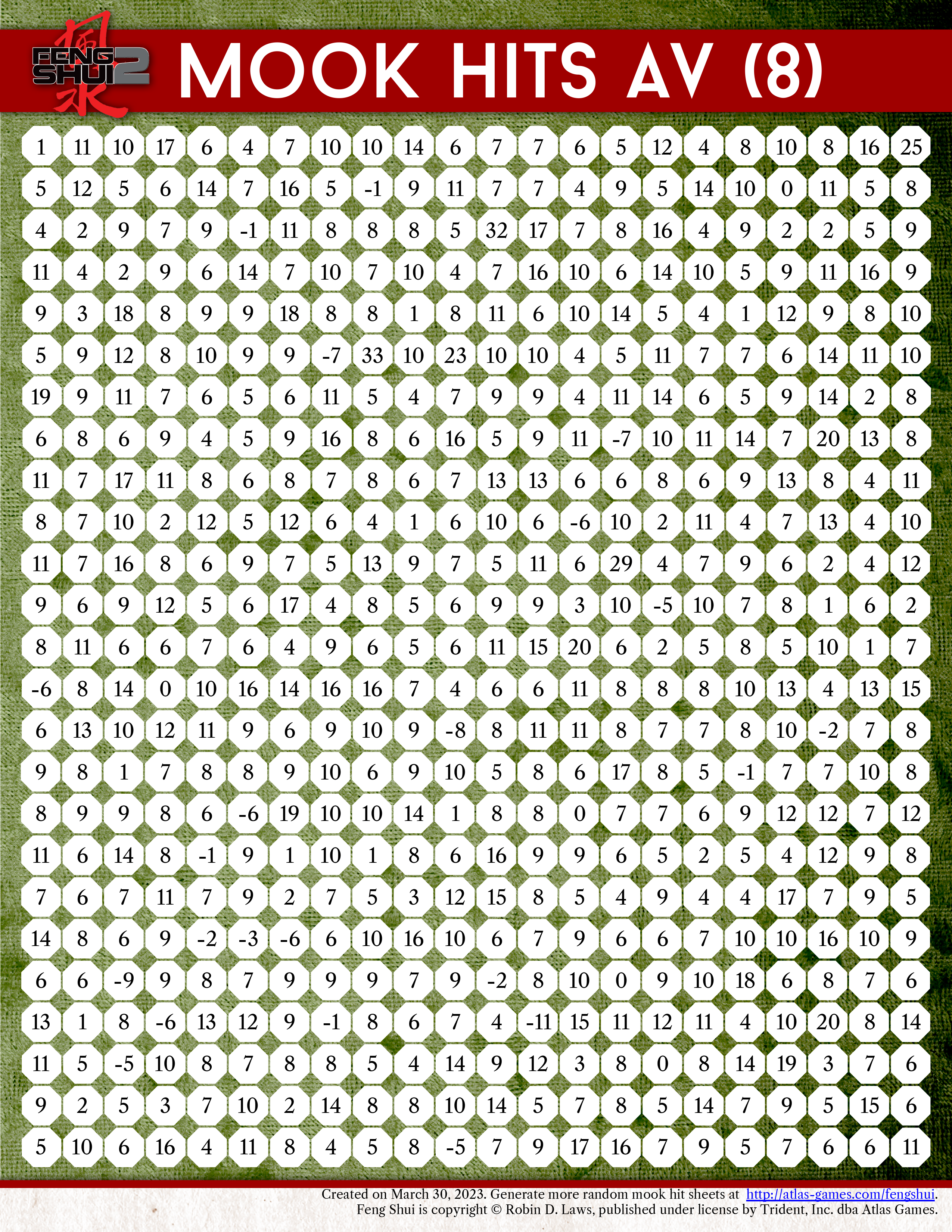

Another option is to use a mook sheet: A big sheet full of pre-rolled mook attack roles. They look like this:

The idea is that, rather than rolling dice, you can just use the values on the sheet, crossing them off for each mook attack.

Atlas Games actually provides an online tool that will let you generate new copies of these sheets.

A problem you can run into with either technique, though, is that — if the mooks all just make straight-up attacks — they can whiff a little too often. This is, of course, what lets you have so many of them in a scene, but if the players no longer feel as if the mooks are a relevant threat it can render the mooks moot.

Fortunately, the solution is a simple technique: combat boosts.

In Feng Shui, characters can perform a combat boost as a 3-shot action to help out another character. A boost can:

- Grant +1 to the recipient’s next attack.

- Grant +3 to the recipient’s Defense against the next attack (and all others in the same shot).

Instead of having the dozen mooks in your fight scene all flail ineffectually, what you should be doing is having each of them perform a combat boost.

You might have the mooks form up into small gangs: Five mooks working together can boost the attack value for one of their number to be roughly equal to a featured foe. A dozen can swarm over a hero, with eleven performing an attack boost and the twelfth packing a boss-size punch.

Alternatively, you can have the mooks group up with a featured foe or boss, either boosting their attacks to devastating levels and/or creating an almost impenetrable defense with their defensive boosts.

You’ll want to make sure to weave these boosts into your narration of the fight: Describe the mooks grabbing PCs by the arms and allowing their boss to land a crushing blow or throwing themselves in front of their boss to take a shot. You could even describe misses as the PCs being unable to get close to the big bad guy through the swirling swarm of mooks!

You want to make it clear to the players that the mooks are the problem, and that they’re going to continue to struggle against the featured foes until they clear out the riff-raff.

Fortunately, it’ll still be quite easy to do that.

They’re just mooks after all.