IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 30D: A PLAGUE OF WRAITHS

September 20th, 2008

The 17th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

Sir Gemmell’s letter only affirmed what Tor had already been planning: In order to keep with his image of loyalty to the Order and to Rehobath he needed to attend his training that day as planned. On the morrow he would meet with Sir Kabel and find out the rest of the story.

But by the time he had saddled Blue and begun riding north into the Temple District, Tor began to be plagued with doubt. What if the letter purporting to be from Sir Kabel was a trap of some sort? Surely he wouldn’t have been so foolish as to sign his own name? Why had the two letters arrived at nearly the same time?

Without having reached any sort of firm conclusion, Tor arrived at the Godskeep. He was escorted to the office which had once belonged to Sir Kabel… and were now occupied by Sir Gemmell.

“Master Tor, I’m honored to meet you.”

Tor thanked him and exchanged pleasantries, but Sir Gemmell was quick to his business. “I know that you were squired by Sir Kabel. I don’t know what his intentions were. But you’re a companion of the Chosen of Vehthyl and so I know that you must be faithful to the Church and to the Nine Gods. Know, then, that Kabel has betrayed both the Novarch and the Gods. His treacherous plots have resulted in the death of many of our brothers.”

“All I have ever wanted is to be a knight,” Tor said truthfully.

“Yes. And with Kabel’s treachery it is more important than ever that your training be completed as quickly as possible,” Sir Gemmell said. “It’s very likely that you will be contacted by Kabel. If that happens, you should alert us as quickly as possible. As long as he remains at large, we’re all in danger.”

“You think I might be harmed?” Tor asked blithely.

“Not as long as he thinks that he has some use to you. But after that? Who can say.”

Tor was given over to Sir Lagenn – a knight of the Order that he had not previously met – for his training. Sir Lagenn was burly and heavy-set, with a shaved head and a vicious, purple scar running from his left temple down to his jaw. Despite his brutish temperament, Sir Lagenn proved to be a competent and able teacher.

But as he trained, Tor’s thoughts were distracted by the two letters he had received. By the time Sir Lagenn called a halt to their exertions he had reached his conclusion: The letter from “Sir K” must be a fake. His loyalty was being test by Sir Gemmell.

Tor returned to Sir Gemmell’s office and gave the letter to him.

After reading it through, Sir Gemmell looked up at him. “Why didn’t you give this to me before?”

“To speak truthfully,” Tor said. “I felt torn in my loyalty between the Order and someone who had quickly become a mentor to me.”

“Well, your loyalty in this matter will no longer be tested. We shall attend to things from here. And do not seek any contact with Sir Kabel.”

“Of course,” Tor said.

Sir Gemmell looked back at the letter. “Why would he ask for the Chosen of Vehthyl?”

“I don’t know,” Tor said.

“Should Dominic’s trust in the Novarch be doubted?”

“I would never question it,” Tor said truthfully. (There was no question about it: Dominic didn’t trust him.)

A PLAGUE OF WRAITHS

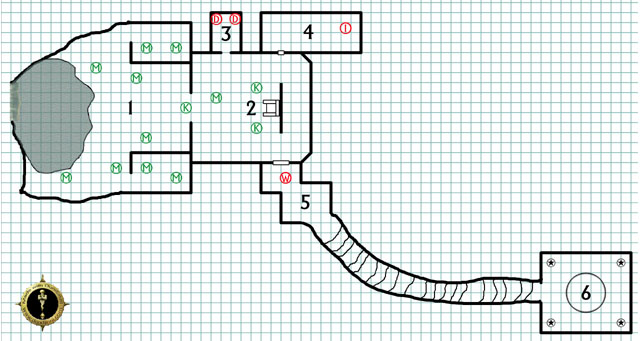

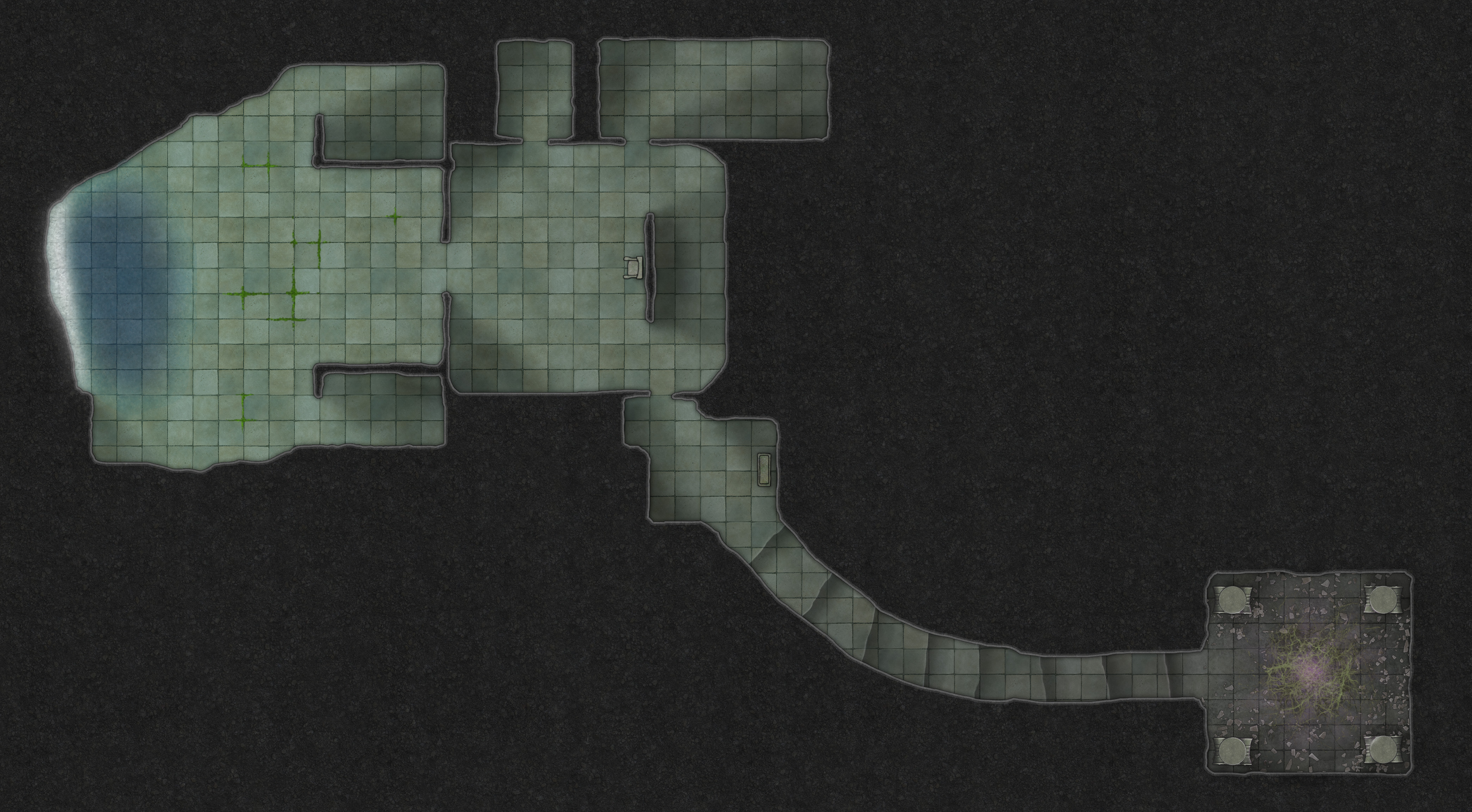

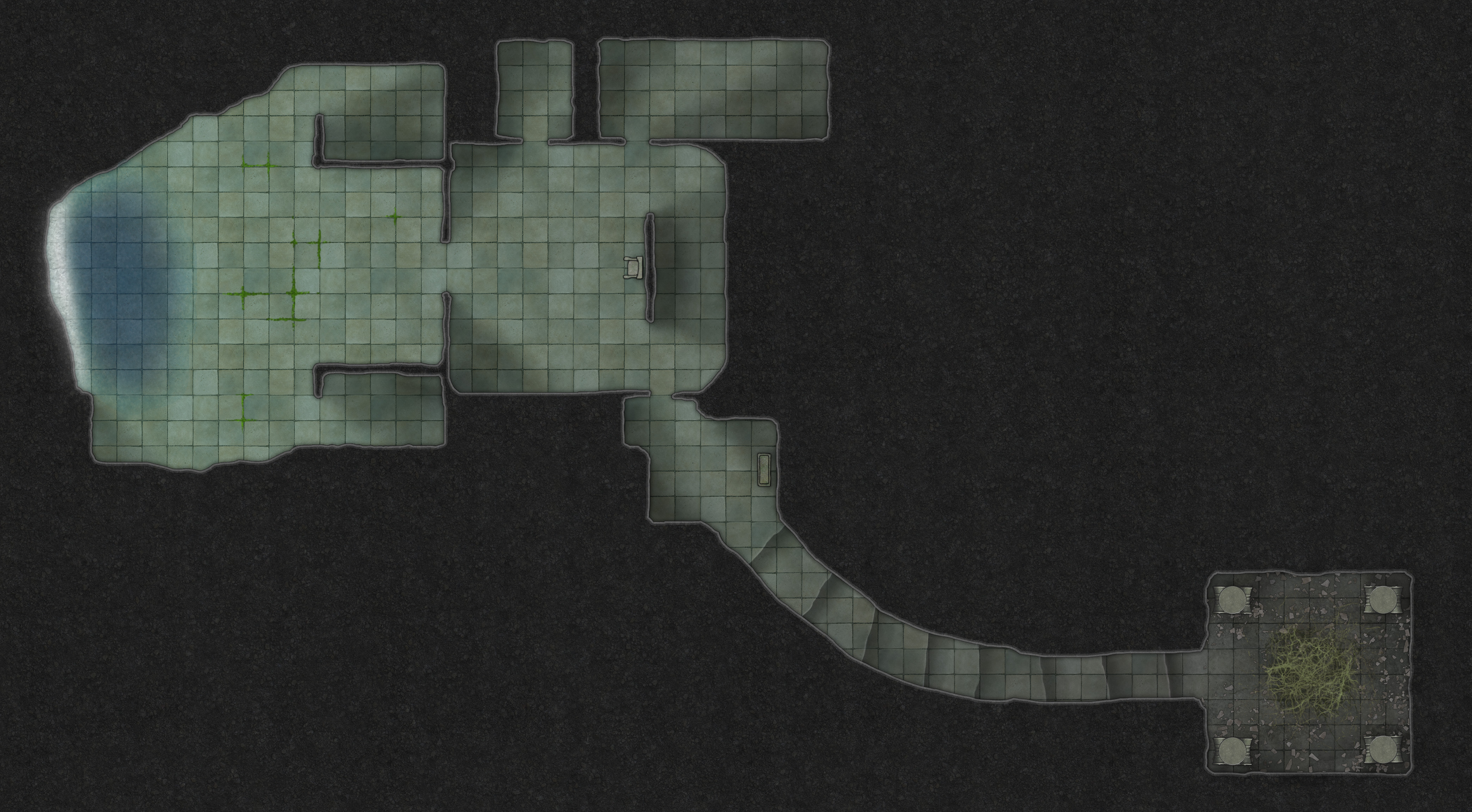

Tee, meanwhile, had returned to the Banewarrens.

While fighting the wraiths the night before, Kalerecent had suffered a wound. At first he had thought it a small and inconsequential thing, but it wasn’t healing properly. In fact, it proved to be beyond the healing skills of both Kalerecent and Dominic combined. As a result, Kalerecent was forced to leave the Banewarrens to seek more powerful healing from the Church.

This proved fortunate, however, when Tor arrived before Kalerecent returned – giving them a chance to converse privately.

“I need to tell you what’s happened,” Tor said.

“Should we sit down again?” Elestra asked.

Tor nodded emphatically and then began his tale.

“And you’re sure the letter from Kabel was a fake?” Tee asked.

“It had to be,” Tor said.

Before they could discuss it further, Dominic heard Kalerecent returning down the tunnel and silently signaled the others.

With Kalerecent back on guard duty and Tor returned they were free to go back to the Banewarrens and continue their explorations.

But Tee had only barely emerged into the first chamber of the Banewarrens when she spotted two purplish wraiths trying to get past the warded door they had shut the night before. One of the wraiths might have been the one they had encountered before, but the other was larger… and shaped like the half-leonid lamia they had slain the day before.

Tee crept back to where Dominic was waiting and told him what she’d seen.

“That’s bullshit!”

“I know,” Tee agreed.

Tee led them back into the chamber. Dominic was considerably less stealthy than Tee had been and the wraiths heard his approach. But it didn’t matter: Raising the cross of Athor, he banished them into nothingness.

Tee went over to the warded door and locked it securely (which proved difficult to do without a key).

“Tee!”

Turning around at the sound of Dominic’s cry, Tee spotted a lamia-shaped wraith and a minotaur-shaped wraith hovering nearby – held at bay only by the divine energy that Dominic was still channeling through his holy symbol. Tee started to move into a firing position, but as she did the wraiths slipped around the far corner and disappeared into the room with the iron cauldron.

Gathering the others they followed the wraiths into the cauldron room. The two larger wraiths were lurking in the shadows here, along with two smaller ones.

Elestra cursed. “It got all of them? We have to kill them all over again?”

Agnarr took the lead and Ranthir took the opportunity to demonstrate how he had used his arcane arts to duplicate Dominic’s feat of divine infusion: He enlarged Agnarr to twice his normal height and girth.

Elestra and Tor worked the corners, keeping the wraiths from circling around Agnarr’s massive shoulders. But most of the damage was actually coming from Tee’s dragon pistol: Agnarr’s blade passed through the wraiths again and again, but frustratingly couldn’t seem to find any purchase in their semi-ethereal forms.

With the battle largely stalemated into one of stark attrition, Tor eventually got daring. Pushing his way past Tee he plunged through one of the wraiths, ripping it apart on the tip of his electrified blade. From there he raced behind the minotaur-shaped wraith, providing enough of a distraction – and a few wounding blows – for Agnarr to finally finish it off.

With the larger wraiths dispatched, the two smaller ones were quickly driven back up the stairs on the far side of the room and overwhelmed. But even as they were finishing off these smaller wraiths, four more of the goblin-spawned wraiths drifted up from behind them. In fact, they were nearly taken by surprise – only Dominic’s wary eyes saved them.

Ranthir hurried up the stairs and away from the wraiths, while everyone else headed down the stairs to face them. But the wraiths – perhaps sensing weakness – passed directly through the walls and emerged to assault Ranthir. Their spectral limbs plunged through him, and Ranthir felt the living breath and warmth of vitality fleeing from his limbs.

Tor dashed back up the stairs and, half shoving Ranthir out of the way, interposed himself between the staggered mage and the wraiths. But in the process, he, too was struck by their soul-icing touch.

Their tactical control of the situation was rapidly deteriorating. They had been flanked, separated, and badly wounded. But Dominic, having barely ducked away from the wraiths’ assault himself, raised his holy symbol again and called upon the power of his faith.

The wraiths fled. As they turned away, Tor destroyed one of them and Agnarr cut down another.

Two of the wraiths escaped and they cursed their luck, knowing that they would almost certainly be troubled by them again.

But perhaps it was for the best. Several of them could still feel the cold, cloying miasma of the wraiths sapping their strength and vitality. Knowing that, as with Kalerecent, only a more powerful channeling of divine energy could alleviate the pall, they resolved to abandon their current explorations and return to the surface.

Running the Campaign: The Undead Sequel – Campaign Journal: Session 31A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index