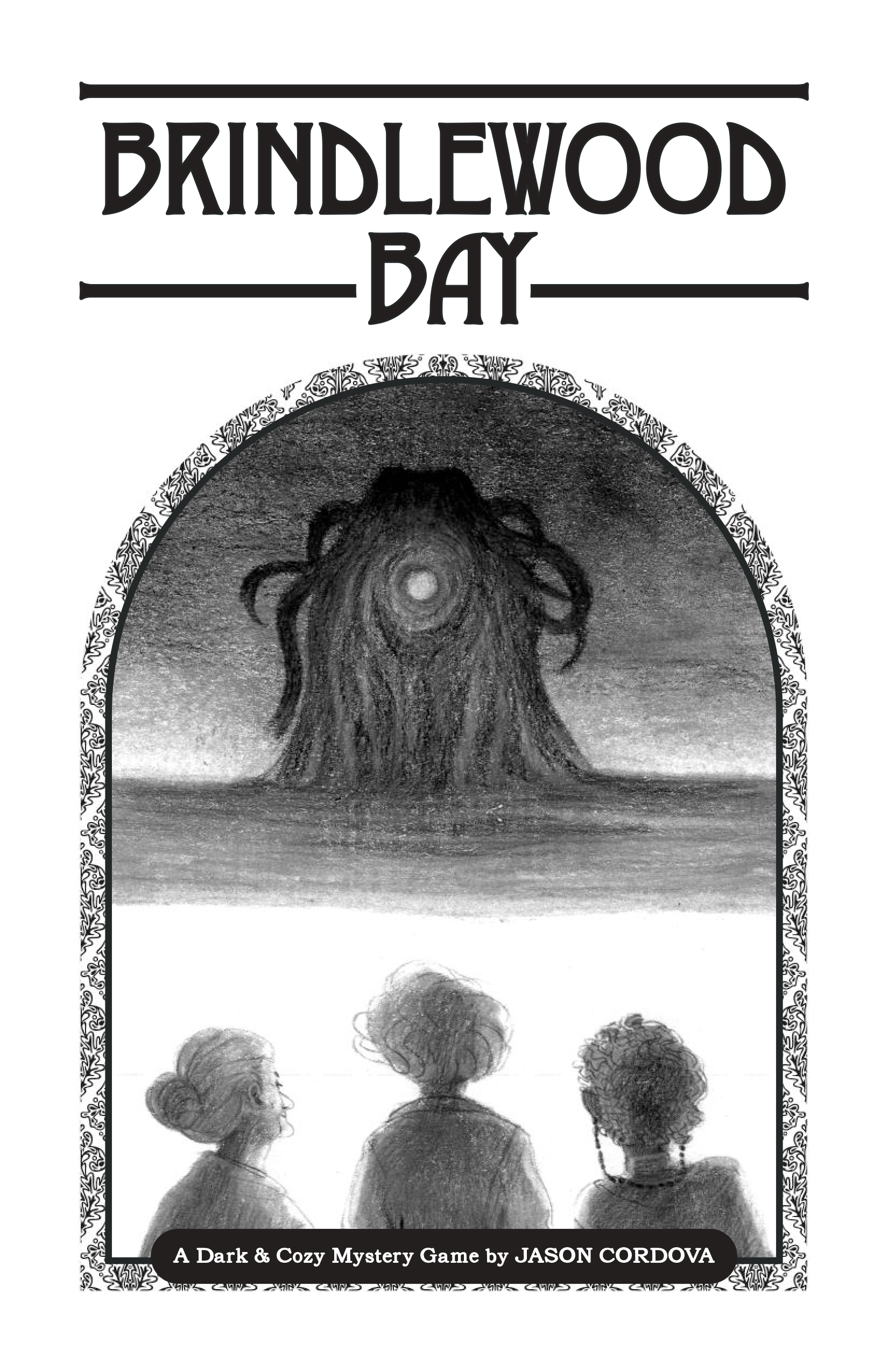

Brindlewood Bay is a storytelling game by Jason Cordova. The players take on the roles of the Murder Mavens mystery book club in the titular town of Brindlewood Bay. The elderly women of the book club, who are huge fans of the Gold Crown Mysteries by Robin Masterson starring the feisty super-sleuth Amanda Delacourt, somehow keep finding themselves tangled up with local murder mysteries in real life.

Brindlewood Bay is a storytelling game by Jason Cordova. The players take on the roles of the Murder Mavens mystery book club in the titular town of Brindlewood Bay. The elderly women of the book club, who are huge fans of the Gold Crown Mysteries by Robin Masterson starring the feisty super-sleuth Amanda Delacourt, somehow keep finding themselves tangled up with local murder mysteries in real life.

And there are a disturbing number of murders per capita in this sleepy little vacation town.

The reason there are so many murders here are the Midwives of the Fragrant Void, cultists who worship the “chthonic monstrosities that will usher in the End of All Things.”

That’s right. We’re mashing up Murder She Wrote with Lovecraft, along with a healthy dose of other mystery TV shows from the ‘70s and ‘80s (including Remington Steel, Magnum P.I., and even Knight Rider).

Brindlewood Bay sets things up with a fast, elegant character creation system that lets you quickly customize your Maven, sketch in their background, forge connections with the other PCs, and flesh out the group’s personal version of the Murder Mavens. Then it wraps the game around a Powered By the Apocalypse-style resolution mechanic, performing evocative moves by rolling 2d6 + an ability modifier with three result tiers (miss, partial success, success). To this now familiar mix, it adds a couple mechanical wrinkles:

- An advantage/disadvantage system tuned for the 2d6 mechanic; and

- Crown moves, which allow you to override the results of a die roll by either playing out a flashback scene (developing and deepening your character) or advancing your character’s connection to the dark forces in Brindlewood Bay, moving them inexorably towards retirement.

The Crown moves, in particular, seem to work very well in play, with the former building organically on the sketchy foundation established during character creation and the latter relentlessly advancing the dark, long-term themes of the game.

Brindlewood Bay’s real claim to fame, however, is its approach to scenario design. It comes bundled with five one-sheet scenarios (and provides guidelines for creating your own), but these notably do not include the solution to the mystery. In fact, there is no solution until it is discovered (created) in play.

Instead, each scenario presents:

- An initial scenario hook that presents the murder,

- A cast of evocative suspects,

- Several locations, and

- A list of evocative clues.

Examples of these clues include:

- An old reel of film showing a debauched Hollywood party.

- A bloody rug.

- A phone message delivered to the wrong number.

- A fancy car, the brake lines cut.

And so forth. There’ll be something like two dozen of these clues for each scenario.

The idea is that the PCs will investigate, performing investigation moves that will result in the GM giving them clues from this list. Then, Rorschach-like, the Mavens will slowly begin figuring out what these clues mean.

So how do you know what the solution actually is?

This is actually mechanically determined. When the Mavens huddle up, compare notes, and come up with an explanation for what happened, they perform the Theorize move:

When the Mavens have an open, freewheeling discussion about the solution to a mystery based on the clues they have uncovered — and reach a concensus — roll [2d6] plus the number of Clues found … minus the mystery’s complexity.

On a 10+, it’s the correct solution. The Keeper will provide an opportunity to take down the culprit or otherwise save the day.

On a 7-9, it’s the correct solution, but the Keeper will either add an unwelcome complication to the solution itself, or present a complicated or dangerous opportunity to take down the culprit and save the day.

On a 6-, the solution is incorrect, and the Keeper reacts.

When it comes to roleplaying games, I’m generally pretty skeptical of the “have the solution be whatever the players think it should be” GMing method. I mention this for the sake of others who share this opinion, because within the specific structure of Brindlewood Bay as a storytelling game it works great.

One key thing here is that the players must know what’s going on here: That the clues have no inherent meaning, that they are assigning meaning creatively as players (not deductively as detectives), and that the truth value of their theory is mechanically determined. I’ve spoken to some GMs who tried to hide this structure from their players and their games imploded.

Which, based on my experience playing Brindlewood Bay, makes complete sense. The game is entirely built around you and the players collaborating together to create meaning out of a procedural content generator stocked with evocative content. (If you’re looking for an analogy, Brindlewood Bay turns the GM’s creative process when interpreting a random wandering encounter roll into the core gameplay.) If the players aren’t onboard with this (for whatever reason), it’s going to be grit in this game’s gears.

But if everyone is on the same page, then the results can be pretty memorable.

For example, in my playtest of the game the players created a really great theory for how the circumstances of the murder came to pass. Then, on a roll of 8 for their Theorize move, I twisted the revelation of who was actually responsible for the death itself in such a way that the Mavens all collectively agreed that they needed to cover up the crime. Simply fantastic storytelling and roleplaying.

There are a couple niggling things about the game that I think merit mention.

First, instead of having the first scenario of the game be the Maven’s first murder mystery, the game instead assumes they’ve been doing this for awhile. (Sort of as if you’re joining the story in the middle of the first season, or maybe even for the Season 2 premiere.) There are kind of two missed opportunities here, I think.

On the one hand, the story of that “first Maven mystery” seems pretty interesting and everyone at my table was surprised we weren’t going to play through it. On the other hand, having posited that the Mavens have already solved several mysteries together, the game doesn’t leverage that during character creation. (By contrast, for example, the Dresden Files Roleplaying Game from Evil Hat Productions assumes the PCs have prior stories in common, but builds specific steps into character creation in order to collaboratively establish those events and tie the characters together through them.)

Second, I struggled to some extent running Brindlewood Bay because the game’s structure requires that the clues be presented in a fairly vague fashion. (This is explicitly called out in the text several times, and is quite correct. Like the rest of the group, the GM doesn’t know what the true solution of the mystery is until the Theorize move mechanically determines it. So the GM has to be careful not to push a specific solution as they present the clues.) The difficulty, for me, is that I think clues are most interesting in their specificity. And, for similar reasons, both I and the players found it frustrating when their natural instincts as “detectives” was to investigate and analyze the clues they found for more information… except, of course, there is no additional information to be found.

The other problem I had as the GM is that the Rorschach test on which Brindlewood Bay is built fundamentally works. Which means, as the story plays out, that I, too, am evolving a personal belief in what happened. But, unlike the players, I have no mechanism by which to express that belief, except by pushing that theory through the clues and, as we’ve just discussed, breaking the game. It was frustrating to be part of a creative exercise designed to prompt these creative ideas, but to then be blocked from sharing them.

These are problems I’ll be reflecting on when I revisit Brindlewood Bay. Which is a trip I’ll definitely be taking, because the overall experience is utterly charming and greatly entertaining. I recommend that you book your own tickets at your earliest opportunity.

Style: 3

Substance: 4

Author: Jason Cordova

Publisher: The Gauntlet

Price: $10.00 (PDF)

Page Count: 40+

I wonder if this would work as a GM-less or rotating GM (per scene) system, which would allow everyone to take part in Theorize. Use an oracle (like Mythic RPG) to lay on the twist and maybe generate scenes/clues.

This sounds fascinating. Just going on your review without having played — as GM, it seems like you can participate in the creative process by having NPCs with opinions, no? “Oh my god, the cops in this town! Why haven’t they arrested Ebenezer yet? I hear freaky sounds from his place all night. Do we have to wait for me to die too?”

Seems like the only thing you’re barred from is that you aren’t required to sign on to the consensus that triggers the Theorize move? If there really isn’t a predetermined solution, then some clues can easily be discarded as red herrings, and any additional detail you as GM embroider in can be seized upon instead?

Very interesting! Can a single mystery/episode be played in a single session? Might work as a “mystery-game night”.

Thanks a lot! I am going to run my own game soon after playing in a one shot and I am glad to see you point out pitfalls in advance!

If I read that correctly, one of your main concerns with running the game is that you cannot express your own theories.

Just from reading the rules, I remember that the GM can actively try to push their theories in the final “Theorize”-move the Murder Mavens take. I also confirmed on the publisher’s Discord server.

Of course, I doubt you can really share all your GM theories bc, in the end, this is about the players “finding” the solution, not the GM taking the job from them.

In addition, I really agree that the approach that the Mavens are already established investigators is unfortunate because, in my opinion, it is not very immersive. As GMs, we should likely try to make the events unfold more around the Mavens in game, not so much have someone approach them with a new case because… they have already solved so many cases before.

I was thinking about the problem you have with the clues, some time ago I was thinking about making a solo game where you as a detective/hunter gather to clues to find a supernatural killer. The idea I had is that every clues creates tags that narrow than “what the killer is”.

I think some kind of move could be made to use the clues in a more interesting way, but I have to read the book.

@Jennifer Burdoo: The game suggests that to run it as a one-shot, to lower the complexity of the mystery a bit, and then “No matter what, when you have about half an hour remaining in the session, wrap up whatever scene is taking place and then go straight to Theorize. If the Theorize move goes poorly, end the session on a cliffhanger and explain to the players you would pick up the mystery in a hypothetical Session Two.” Still, I imagine it depends how long your sessions are and how much your group is used to getting done.

I went out and grabbed a copy on the strength of this review. Looks cool, though my first reaction without playing it is that I expected there to be some more advice on how to handle threats and enemies without breaking the cozy tone. I’m especially surprised that it doesn’t include even an example of a summoned servitor. I mean, yes, I suppose we all already have copies of Call of Cthulhu, but Brindlewood Bay does make gestures at creating an original mythos, but then doesn’t follow through at all.

@Ceti yup, there’s actually been talk about randomly generating a threat and running the game GMless. Furthermore, there’s an entire game out that uses the Carved from Brindlewood mystery system, but generates the locations, events, NPCs, and clues from a deck of cards. It’s completely GMless. It’s called Paranormal Inc, if you want to check it out.

@Justin I don’t have access to my copy of Brindlewood Bay here, but I do have The Between (basically Penny Dreadful with the same system as BB) and there’s some GM advice about the mystery solving: “The text of the move says, “When the hunters have an open, freewheeling discussion…” but, in practice, this discussion is being had by the players, not the hunters, and, as the Keeper, you have a role to play, too. You should feel free to offer your own thoughts, challenge the assumptions being made, and interrogate theories that fail to account for certain Clues.”

Basically, I think it’s okay as the GM to input your own thoughts about the mystery! At the least, you’re encouraged to poke and prod at the theories being developed, and to ask for critical context about clues, and help out where it’s needed. I’m not sure if all that’s *enough* to feel involved, but I really enjoy that part of the game, where the whole table is helping to “solve” the mystery, GM included.

@colin There actually is a section in The Gauntlet’s most recent zine which I think will be added to the upcoming hardcover release of Brindlewood Bay. It includes a ton of Keeper advice, including example Servitors! Pretty cool stuff.

@Xander: which issue is that? I just looked at the Codex index and don’t see anything that sounds like that.

@Ceti

There is a version of this game like that. A GM-less iteration by Alicia Furness called Paranormal Inc.

https://afurness.itch.io/paranormal-inc

@ColinR

The issue of Codex is “Void 2” and came out on January 1 2022 (i.e. three days ago as I post this.) At the moment, it’s only available to Gauntlet Patreon subscribers. It should become available for sale on DTRPG in 2-3 months.

It looks like the Codex Index on the Gauntlet website hasn’t been updated with the latest issue yet. It should be sometime this week.

@colin It’s the new Void issue. It was released early on Patreon but isn’t “out” yet.

Ah, well! Seems it’s cheaper to support the Patreon than buy from DTRPG anyway.

Just played our first session of Brindlewood Bay, and I’m quite happy with how it went.

A few lessons: * it’s possible for players to crank out the Clues very quickly if you are permissive with letting them use the Meddling Move and the Cozy Move. It’s not difficult at all to rack up 6 or 7 Clues before the Mavens have even met all the Suspects. In a campaign I think I will be a little particular about demanding some role-playing before allowing them to roll the move, for pacing purposes if nothing else. In a one-shot that was fine, but it helped a lot that my suspects weren’t shy about venting their opinions.

* I think it’s good to be pretty aggressive about pushing the Suspects on screen at any opportunity. Have them wander into discussions and yell accusations at each other. And be aware that any given Suspect might only appear on screen once before the players get to theorizing who did it. My impression is that the more information the players have about who the suspects are and what their motives might be, the more compelling the Theorize move will be.

* When you do introduce Clues, it seems perfectly cool to get specific with them. Like, it’s okay if the line in your Keeper notes just says “An argument between two Suspects on deck”, but when you describe it to the players you give each of the Suspects some lines and write it down on the players’ Clue list as something more like “An argument between Sara and Emily – Emily doesn’t care that Albert is dead; Sara’s husband got something over on Albert”. Even with that kind of concrete specificity in the clues, the players still had more than enough freedom to concoct cases against three or four of the Suspects. If we hadn’t been rushing a bit to get it done as a one-shot, I would have told them they should go out and investigate some more to help them settle on a single culprit, but we ended up having to have a vote.

* Asking the players, after they got a successful Theorize, “So, if that’s who did it, where will the conclusive evidence be found?” worked pretty well.

* In character creation, to give the feeling that they all knew each other, I asked them to decide which pair of Mavens were old friends, which were new friends, which were friendly rivals, and which were connected by a marriage in their families. Not sure the answers really came up in play, but it felt like a worthwhile bit of embroidery anyway.

Great review / write-up and a really useful set of responses.

Thank you!

I’ve got a hankering to GM this and the observations / suggestions offered have made me much more comfortable with getting involved.

(I love Lady Blackbird and this seems like similarly inspired game.)

InSpectres by Memento Mori Theatricks has a similar improv mystery structure tied to a Ghostbusters-inspired “running a business” framing. It’s a lot of fun and may be entertaining to folks who enjoy Brindlewood Bay.