This is the first entry in a new series I’m trialing here at the Alexandrian. Back in 2012, I wrote a series of essays about Game Structures in RPGs. A major component of this discussion concerned scenario structures – the macro-game structures which allow the GM to prep different aspects of their campaign world and different experiences for their players.

One of the specific things I discussed was the fact that when you try to prep a scenario using the wrong scenario structure, the result can be painful for everybody involved. You can see this with clearly wrong-headed ideas like running dungeon exploration as a linear timeline of events; running conversations using combat initiative; or trying to have players navigate a city as if it were a dungeoncrawl (by prepping every street with a keyed encounter and having the players make intersection-by-intersection navigation decisions).

This makes it truly unfortunate that most GMs don’t have a robust library of scenario structures that they can use to build their campaigns. In my experience, the vast majority of GMs are limited to just three structures:

- Railroads

- Dungeoncrawls

- Mysteries

In actual practice it’s usually worse than this because many GMs don’t really understand how to structure mysteries, so they end up defaulting back towards railroads for their mystery scenarios.  And even running a dungeoncrawl is no longer a reliable skill for many DMs because the gateway game, D&D, is no longer teaching it as a skill: The actual procedure by which a dungeoncrawl is run was significantly obfuscated in 3rd Edition and was completely removed from the rulebooks for 4th Edition.

And even running a dungeoncrawl is no longer a reliable skill for many DMs because the gateway game, D&D, is no longer teaching it as a skill: The actual procedure by which a dungeoncrawl is run was significantly obfuscated in 3rd Edition and was completely removed from the rulebooks for 4th Edition.

The result is that GMs generally don’t even consciously realize what scenario structures are, so they end up just kind of muddling around using gut instinct and a random amalgamation of half-realized scenario structures they’ve picked up through osmosis, most or all of which are just various flavors of railroading.

So I obviously think it’s really important for GMs to make the conscious decision to think about the scenario structures they use, and make sure they’re using the right scenario structures for the scenarios they want to run (or which they need to run because of the decisions their players are making). One of the things that storytelling games have been doing very well compared to RPGs over the last ten to fifteen years is, in fact, spelling out specific procedures for GMs to follow.

As part of that original series on Game Structures, I also talked about designing custom game structures, using the example of how to design structures for running a campaign about a starship plying interstellar trade routes.

With this series I want to challenge myself – and you! – to do more of this. The truth is that even one of these structures unlocks the ability to confidently prep and run dozens of scenarios. When I figured out node-based scenario design, it meant that I could suddenly design and run incredibly complex mystery scenarios as a matter of simple routine. When I figured out the party planning structure for effectively running large social events, it was like opening a door to a room that I’d never even knew existed. What else is hiding out around here, lurking just within arms reach and yet somehow completely beyond our grasp because we’re blind to the possibility?

So this series is going to look at specific types of experiences and say, “How would you prep this – and then run this – for an RPG?” The results won’t have been playtested (yet!), so it’s possible that what we come up with won’t work in actual practice. But the goal will be to get specific enough to provide a concrete framework for prepping any number of scenarios. Or, if we run into something truly challenging, enough detail to spark meaningful analysis and discussion (similar to my Thinking About Urbancrawls series, which did, eventually, result in a specific structure being created).

I suspect that most of our challenges will be prompted from linear mediums like films, books, and comics, but real life could also easily provide examples. (Hexcrawls, for example, were born as much from the inspiration of real life expeditions like Shackleton or Marco Polo as they were from the travel sequences of The Lord of the Rings.)

Of course, some would-be “challenges” will have obvious answers: Sherlock Holmes? Well, Three Clue Rule with a side-helping of node-based scenario design. Next!

Of course, some would-be “challenges” will have obvious answers: Sherlock Holmes? Well, Three Clue Rule with a side-helping of node-based scenario design. Next!

We’ll be skipping those.

Our goal is also not to specifically ape our point (or points) of inspiration: Even if we could create such a narrowly focused scenario structure, what would be the point? What we’re interested in is finding a structure that will allow us to create any number of similar experiences, preferably with so much flexibility that the results might end up looking absolutely nothing like our original inspiration. (Think about how something like Moria becomes the incredibly flexible structure of the dungeoncrawl, which in turn expands into the generic structure of the location-crawl, which can end up being used to model a technologically-riddled skyscraper in a cyberpunk setting.) The points of inspiration exist to help us think about and unlock that structure.

I’m also hoping that seeing my process of working through these challenges will also prove more generally useful by demonstrating the process by which I create and prep these structures.

Finally, I really do want to be challenged here. So if you have some tricky situation or a narrative example of an experience you’d like to create for your group, throw it my way, either in the comments here or via Twitter.

We’ll be getting stated on Wednesday with…

SCENARIO STRUCTURE CHALLENGES

Challenge #1: The Death Star Raid

Challenge #2: Race to the Prize

Challenge #3: McGuffin Keep-Away

Challenge #4: Heists

Challenge #5: The RPG Montage

Challenge #6: Innkeepers

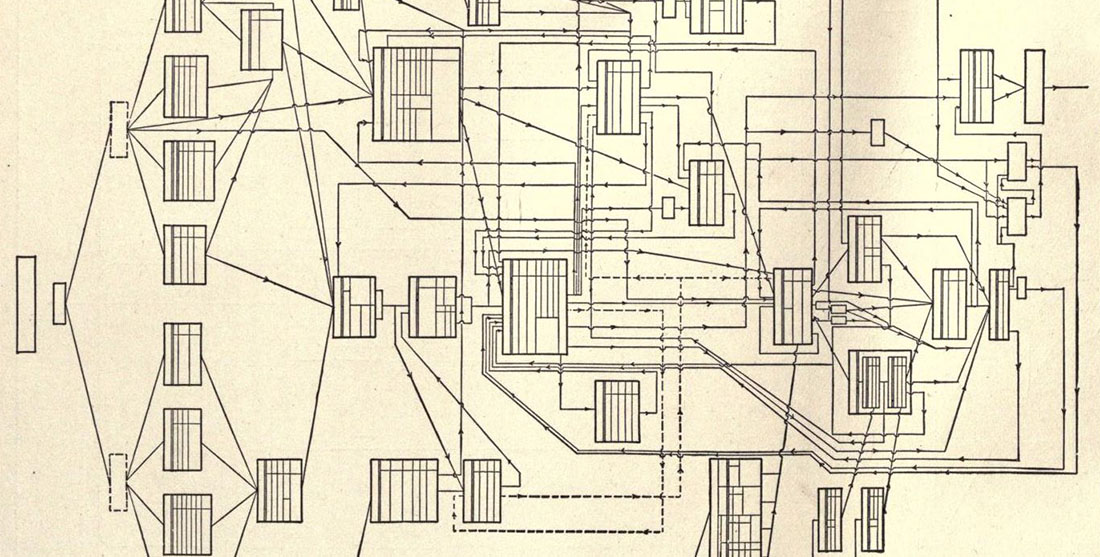

I’ve been trying for years to create a usable format for playing out company to army sized battles. Few published materials have ever given me any guidance: One of the worst, 3.5’s Heroes of Battles had each battle being a flow-chart style railroad in which the PCs had to move from preset encounter to preset encounter to preset encounter, and required the GM to prepare material that would never be used. Even before reading your essays on the subject I recognized this as unusable.

Better modules include Red Hand of Doom and Battle of Bloodmarch Hill. But the big battle sequences there are still preset encounters which the PCs must deal with or lose victory points. I’ve never been able to develop a structure to run a battle in which the PCs hit the ground (with or without orders) and have open reign on how to participate in the fight.

I should add, I like the victory point model of both Red Hand of Doom and Battle of Bloodmarch Hill, as I have not been able to model a better way of having PCs interact with and have an effect on a battle.

I think it would be interesting to try and make a structure for really tight chase scenes. A lot of games have some rules for these… yet in my, admitably limited, experience these turn either into flat out railroads or are essentially a series of varied skill checks.

“The guy vaults a wall to escape, roll Acrobatics!”

Sometimes they get slightly more complex and offer options such as;

“You can vault the wall using Acrobatics OR you can use Intimidate to force your way through the crowd!”

Yet they seem hard to actually have as THE SCENARIO rather than a single beat within a larger scenario. Perhaps because a chase needs to be failable to not constitute a railroad, but failing to chase someone is somewhat of a hard failure on maintaining a chase scenario (it changes into an investigation/track of where the person went).

Hopefully that makes sense!

So very excited for this series.

I have thought about doing chases using a sort of revolving beltway of dungeon tiles. When the PCs (or people they’re chasing) run off the map, just push the dungeon tiles back and put several more in front. This works well in places like wilderness. If the quarry ever gets so far away as to get fully off the map from PCs, you could say they escape or have the party need to use tracking to pick up their direction. In order to prevent simply dashing continuously, you’ll need obstacles, enemies, treasure, shortcuts, etc. I think you could make things into a better game-like structure by rolling a die based on CON or STR or athletics to see how fast people, or perhaps just use modifiers to affect movement distance if you want to reduce rolls to keep pace. Plus points for the quarry to have to carry something heavy (like treasure or an injured comrade) to make the chase more interesting.

I wasn’t able to try this myself. Prepped the chase, but my PCs just cast Pass Without a Trace and I couldn’t figure out a reason why it wouldn’t just prevent pursuit in dense woods. I would love to hear other people’s ideas for running chases though. It is really exciting and an important part of realistic combat, because most everyone tries to run when they think they’re losing.

I have been working with a mapless, shared-storytelling, goal-oriented dungeoncrawl (really a facility-crawl because it is for Shadowrun: Anarchy). Players make rolls to determine turn order and to determine progress toward a Threshold (similar to a skill challenge). Each player, in turn, then sets up an encounter (which could be a challenge or complication, a social or role-play scene, or a combat scene). That encounter is then played out and the next player sets up the next encounter until the Threshold is met, then they reach their goal. It works well as it lets the players spotlight their own character and it lets the players dictate the encounters to match their appetite. Do they feel like fighting? Do they feel like tricking their way past some guards? It works.

My problem is trying to figure out how to work this when the party splits up. Because Shadowrun is a mission game, and the players have specialties, the team often needs to split up to accomplish related but different goals. If the group is split, and player A sets up an encounter for players A and B, what do players C and D do? Does player A set up an encounter for C and D too? Do I try to to time two encounters to finish at the same time? I don’t want to sit anyone out. Perhaps it is not a structure issue?

Oh, cool. Yes, excellent series!

I’m with brotherwilli on this one. Running large-scale combats or even decent-sized skirmishes have always been a pain in the ass to run. Especially when you have PCs stuck fighting in the midst of it who may or may not influence the course of battle.

Great stuff here, thank you.

There are a few scenarios that I am less than happy with handling.

Chase in an object-rich environment… the time resolution could vary from across the city to across a continent….and its mirror the Escape.

The stealth infiltration/exfiltration ((looks like you will tackle this next), for assassination, theft, kidnap, spying

Escape/survive from moving engulfing disaster – flood, fire, tsunami, burning/collapsing building, Pompei, rioting city, caught in a stampede, large battle.

Power politics – Garnering support/alliances from various influential actors – could be getting fealty from lords of the realm for the boy king against his uncle the Regent, or drumming up support or dissent for a ship mutiny

Realm building/support – homestead, manor, village, guild, mercenary company, bandit gang….security, resources, labour, prosperity, trade/income etc

K

I’ve always wanted to play out a heist movie. Especially the idea of using flashbacks to reveal previously unseen preparations that get the players out of their current jam.

Like the reveal in The Sting that the cops that have been chasing Robert Redford are actually accomplices. Or the flashback in Ocean’s Eleven that reveals that the swat team officers who took away the money were actually members of the gang.

I’ve tried it before with varying success, usually with nothing more complex than giving each player and the antagonist a set number of cards each session that they can use to initiate a flashback and explain how they prepared a way out of whatever jam they are in. It’s worked pretty well as a fun change up for one session of an ongoing game, but I’d love to hear others’ thoughts on a more codified version that could be used multiple times.

Regarding large conflicts involving PCs… if you’re talking about very large forces (armies) in battle, the first question is whether the PCs can really have a significant influence on the outcome (other than in a “for the want of a nail…” kind of way). Delta (http://deltasdnd.blogspot.com/) has done some work in this area, with an OD&D slant (see OED: Book of War). But unless the PCs have battlefield-altering power, they are probably just fighting for survival, or engaged in some special mission (raiding behind the lines, trying to take out the enemy spellcaster, something like that) that you could probably handle in a kind of node-based manner.

For smaller skirmishes, I wrote up a couple pages of rules to treat units of up to 10 figures as a single entity that can fight (and attack/be attacked by individual figures). This keeps the regular D&D scale (6 second rounds, 5′ squares) but allows fast resolution of attacks and damage, so it would be practical to have say 50 or 100 combatants per side and not bog down too much. I think it’s not online at present but if anyone is interested I could probably throw it up on Dropbox or something.

This might count as a subset of large social events, but I’d love to see you explore extended, high-stakes gambling/gaming scenes, where the gambling/competition serves as the basic structure and pacing element, but PCs and NPCs might be maneuvering against each other in all sorts of ways (physical, psychological, and otherwise) during and between rounds. The central poker game in Casino Royale is of course the best example of this.

Can’t wait to see this. Your articles are always very helpful. I have to go back and read your party planning article. (Thanks for the link!) I’ve been wanting to do something like that.

@Greg : Have you heard of The Sprawl? It is a Powered by the Apocalypse game that is all about cyberpunk mission running, which obviously plays well with the heist concept.

The way it structures those flashbacks and earlier preparations are by splitting each scenario into two phases; Legwork and Action.

The Legwork Phase is all about hitting the streets, talking to contacts, using character special moves, etc. in order to generate both the fiction of the mission but also to accumulate [Gear] and [Intel] which are intentionally undescribed resources.

The Action Phase is the actual ‘job’ of carrying out the heist, assassination, chase, etc. and during this phase, you can use the [Gear] and/or [Intel] you have built up to complete the mission.

So let’s say I’m playing a Tech and during the Legwork Phase I used a generic Move called Research. I explain how my character logs into cyberspace and starts tracking down plans and data about the building we are going to rob. That’s it – no need to be any more specific yet!

Then later during the Action Phase our plan goes to hell, the exits have been locked and our hacker can’t override them! Well, good thing I did that research earlier… I flash back to that Move and then explain how during my Research I came across detailed floor plans of the building, ones that even included the layout of the ventilation shafts. Not only does my character now have that knowledge, they also get a bonus on any roll to do with it (say, on a roll to defend the air vents from Ecuadine Corp Vent-Killbots while the safe is still being cracked).

Gear is the same principle. Security system deploying tear gas through those air vents? Good thing I used my Character Move ‘Storage’ before the session to dig through my tech lab during the legwork phase because now I can declare that in my prep I saw the gas deployment system and brought with my stash of micro air-purification masks!

This is already quite a long description, but the process is actually relatively straightforward. Some flashbacks can literally just be simple descriptions like I have provided or can be entire scenes, especially relevant for things like roleplaying whole conversations with Contacts.

@Sarainy: I’ve played some PbtA games before (Monster of the Week and Dungeon World), but I hadn’t heard of The Sprawl. Thanks for the suggestion, I’ll check it out.

I’ve been dying to find a structure that allows multiple characters to participate in and contribute meaningfully to vehicular combat. Specifically, sailing ships or space ships. Too often my ship-to-ship combat becomes one person making rolls while others look on. I’d like to find a good way to simulate multiple people running around a ship, making repairs, boosting shields, diverting energy, firing weapons, etc. – AND have all of those things meaningfully affect the outcome of the combat.

By the way – your series on game structure was AMAZING. I read the whole thing in a few hours and found myself looking at every game I had ever run in a completely new light.

A couple of examples that interest me:

On the encounter level, how to do negotiations or something like the board meeting you mentioned in the party planning articles. Especially when their are multiple factions or across which will have different goals.

On the adventure level, I’ve been interested in running arbitrage or trade without using Adventurer Conqueror King System, as I feel it is a little too involved. I suppose this could also incorporate something like making sales contacts or could be really be repurposed for things like smuggling, pushing drugs, or buying or selling rare or illegal artifacts or magic items.

I’ve been toying for a while now with procedures to support the sort of territory and army building high-level campaign that was suggested by the stronghold and followers options in D&D 1e. Your thoughts would be appreciated. If I get a chance, I will post my own thoughts and link them here.

For the people who mention mass combat above I find that, in systems that support it, swarms of low level combatants work well. PCs can then be given command of a unit, expressed as a swarm of troops. Its easy to run because the troops are aggregated, and the PC doesn’t have to be individually powerful to affect the battle, just an effective leader. However, the scenario has to be one where the PCs have the freedom to choose their tactics, for example, “hold that hill” offers more freedom than “hold the line,” which more or less bakes the necessary tactics into the order.

@ Greg: Another game that comes to mind is Leverage. I haven’t read the entire rulebook myself, let alone played or run it, but it’s explicitly designed for running capers, and I’m pretty sure it includes rules for flashbacks.

@ Justin: How would you run a game inspired by shows like Downton Abbey?

So very excited for this series!! Cyberhacking comes to mind.

I was honestly not anticipating this much enthusiasm!

Let me start with the first comment. @brotherwilli: Mass battles are a tough nut to crack. I took my best swing at it 15 years ago with THE ART OF WAR… a product which never saw print because the 3.5 revision happened. My solution there was three different systems: A detailed tactical engine similar to RPG combat; an abstract “Commander” system that could be used for resolving battles when the PCs were leading troops; and a scene-based resolution system not that dissimilar from the sequence of preset encounters that you discuss.

Something you’ve said here has sparked a new thought, though: I think part of the problem is that we try to cram too much into a single scenario structure. There are actually a lot of different stories/experiences that happen in a mass battle, and a single structure/system doesn’t need to handle all of them simultaneously.

It might be interesting to (at least initially) simplify the problem by looking strictly at a scenario in which the PCs are on the battlefield, making meaningful choices within that battlefield, but not necessarily changing the outcome of that mass battle. (Once you crack that nut, then you could look at how to bolt on additional components to add that “affect the outcome” functionality to a scenario structure that was fundamentally working.)

I’m thinking SAVING PRIVATE RYAN would be an interesting model to look at here. Anyone have thoughts on other source material to crack apart?

@Sarainy: I’ve been trying to crack chase sequences for years. They’re a tough nut. I’m not sure this series will necessarily branch out into all game structures (mainly because functional mechanical structures tend to require a bit more elbow grease to be useful), but here’s the next paradigm I’m thinking about exploring with chase mechanics:

A chase is fundamentally about one party creating a situation to which the other party has to respond. (And, optionally, a random element where the environment imposes a situation. Maybe a scheduled random encounter check like an OD&D dungeoncrawl would work for this?) So what you really need is to clearly define who has the right to create a situation; how they create that situation; and how the situation is resolved.

The other thing you need, of course, is the ability to adjudicate the end of the chase. And I wonder if this is actually where chase mechanics fall apart; because they try to encompass all possible chases into a single, generic structure. OD&D, for example, actually has one of the most functional chase mechanics because it models precisely one thing: PCs running away from monsters in a dungeon.

Although, from a generic standpoint, I wonder if you could almost embrace a tennis approach: So at any given point in the chase one party has the “initiative”, which gives them the ability to create situations in the chase. The other party has to respond to those situations (they’ve knocked over a stack of boxes and created an obstacle; they’ve done an incredible acrobatic maneuver and you have to figure out how to keep pace with them; etc.), and they would also have some mechanical structure to seize the initiative so that THEY can start creating situations.

Hmm… Definitely stuff to think about there.

That’s all I’ve got time for now, but I’ll come back and continue responding as I have the opportunity.

Here are a few challenges.

For a mass battle, the attack on the Spanish fort in the movie Retribution of the Hornblower series:

(Two six minute videos)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kja6UQ28oDg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaTn839eVxA

This has a lot of interesting stuff. There’s a hostage negotiation, scouting, stealth, commanding troops, deducing the existence of a secret passage, blowing up a wall, and ending the combat by getting the opposing commander to surrender.

The foot chase in Point Break.

The speed boat chase at the beginning of the James Bond movie, The World is Not Enough.

(6 1/2 minute video)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OhfCY0J9E3Q

@Justin: Being able to run a “Saving Private Ryan” moment would be awesome. Similar movies that spring to mind are “Troy” or “Enemy at the Gates.” The PCs aren’t in command of the battle – they may not even be able to influence the battle – but there’s a wide ranging conflict of massive scale around them, and they have their orders.

@ Cail: Check out the starship combat rules for Starfinder: http://www.starjammersrd.com/game-mastering/starship-combat/

I would think that the D-Day sequence from Saving Private Ryan would be best handled by a system akin to a Dungeon Crawl Classics funnel. Roll up a bunch of characters (simple ones!) and then play through until you’ve funneled down so a very few are left.

You can start with a whole boat section of 24 guys and run it down until you have only a few left.

Of course this only works if you have a simple character creation system and a very deadly environment.

[…] The Alexandrian pointed out recently, the 4e DM Guides express no procedures for handling exploration. This is […]

I said I would post my thoughts on procedures to support a D&D 1e-style territory and army building high-level campaign. You can find them here: https://campaignunderdeconstruction.wordpress.com/2018/06/14/lord-level-campaigns-beta/

As someone else said I would be very interested in a large scale warfare type scenario.

I have been trying to get the feel right in my Star Wars Campaigns, particularly Age of Rebellion and I feel like I haven’t quite got it yet.

I have been trying to create a Star Wars Battlefront/Battlefield vibe that I feel like I keep missing.

Thanks for this series I really like it so far.

@Gingivitis: Might be interesting to check out Robin D. Laws’ RUNE. It featured a formal structure for shared GMing of challenge-oriented scenarios similar to what you’re describing with Shadowrun Anarchy. I actually have a half-finished draft of a post from 4 or 5 years back floating around called 4TH EDITION UNLEASHED! that would have applied Rune-style structures to 4th Edition’s My Precious Encounter(TM) scenario design to produce something potentially of interest.

@Kim Theakston: Great ideas. Any thoughts on good media points of reference for these (escaping from natural disasters, power politics, realm building/support)? Re: Realm building specifically, I do recommend checking out Stolze’s REIGN. It actually lacks a robust scenario structure, but as a mechanical cap system it has a lot of utility.

@Greg: I still haven’t had a chance to try it out, but for heists like you describe you might want to check out BLADES IN THE DARK. I also like the set-up and pay-off stuff Sarainy is describing from The Sprawl; it’s more satisfying to my sensibilities than a pure “rewrite reality” flashback mechanic.

@Cail: I think the trick with ship combat is to very firmly enforce action economy. Systems often allow pilots to do EVERYTHING; the worst allow the pilot to also default all vehicle actions back into their Pilot skill (instead of, for example, requiring combat-related tests to shoot the guns). What you need to do is:

(a) Making high quality piloting interesting;

(b) Require the pilot to choose between piloting and doing something else;

(c) Divide the skill load across several different niches

(d) Provide enough stations onboard the ship for everyone to have a specific capacity to contribute

This is basically the approach I adopted for the basic vehicle rules in Infinity, although the mecha-based vehicles in that game required a mechanical loophole for vehicles specifically designed to be piloted solo.

An interesting non-RPG example to consider is the ARTEMIS starship simulator game.

@Edogg: You’ve finally gotten me to move Hornblower to the top of my reading list instead of just toodling around in the middle of it.

Please turn this into a kickstarter project. This, along with your font prep plots, would be super useful and popular. I’ll help review if you want.

> @Edogg: You’ve finally gotten me to move Hornblower to the top of my reading list instead of just toodling around in the middle of it.

The Hornblower novels are a lot of fun. As are O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin novels (Master and Commander, etc), which have in addition to the naval stuff some very very dry humor as well as literary allusions to enjoy, if you’re paying attention.

The early-career Hornblower novels were written later, so there are a few things that feel a little bit odd in the timeline (like, just when DID he meet Bush for the first time), but I think they’re some of the best of the bunch.

There are factions slowly lining up for a fight. PCs are connected to people or places that may be harmed or destroyed if the fight happens. Its tense. Is there someone pushing for the fight in the background? There is a mistake. Is there a set of misunderstandings that could be corrected or will they lead to tragedy? Are egos, spite, prejudice or ignorance driving antagonists?

Thank you very much for this series of essay!

As far as I understand your terminology, not all game structures are scenario structures. For example, combat is a game structure, but you do not list it in your list of scenario structures (although you can run a short game using combat structure exclusively). So, maybe it is interesting to think about other non-scenario game structures, such as stealthy actions (to go past guard post without combat or to lay an ambush) or social interactions (to fast-talk guards so they let you go past instead of killing them in combat). Or, if we do not need game structures for such actions, it may be interesting to think about difference between them and combat.

Now to scenario structures.

1. Really tight chase scenes, mentioned above, are, of course, interesting, but it may be easier to start from a long-term overland pursuits with some track-finding and path-finding, such as the the Three Hunters (Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas) pursuit of the Uruk-hai. It also may be useful to think about chase structure as an addition to other structures (hexcrawl for long-term pursuit, city-crawl for chase in the crowded city streets and so on).

2. It may be useful to have a separate from hexcrawl (or additional to it) scenario structure for traveling from known point A to known point B, without lots of land exploration and maybe staying on roads or paths all the way, such as the main plot of the Hobbit and (less so) the LotR. I think, this structure is named point-crawl, and its relations to hexcroul are similar to relations of raid structure to dungeon-crawl.

3. Another useful scenario structure may be daily life and survival in (more or less) hostile environments. Literature examples of such scenario are “Robinson Crusoe” and “With the indians in the Rockies” (by James Willard Schultz).

I am looking forward to read your opinion about (some of) this scenario structures.

(Excuse me for mistakes, I am not native English speaker.)

Have you ever thought about or chanced up a good crafting scenario structure. Because I keep getting begged by one of my players to implement something, and my searching around so far hasn’t been fruitful.

The best I’ve found so far has been Ars Magica, but while the crafting rules are certainly interesting, they’re unfortunately rather incomplete, as there doesn’t seem to be any kind of guidelines on how to get materials (neither for vim nor the mundane components). They’re also optimized for their purpose of crafting spells, and not easy to adapt when you want a system capable of crafting equipment (but not only equipment).

How about a challenge about time travel ?

It usually makes good stories on paper or on screen, but time travel seems to be a difficult theme to create robust scenario structures.

Here are some more specific ideas:

– Groundhog Day / Edge of Tomorrow (being stuck in a timeloop)

– Umbrella Academy: Trying to avoid the apocalypse with clues from after the apocalypse

– Back to the Future 2: Helping yourself without disturbing the timeline

– …

In short, my challenge is to build a viable and entertaining scenario structure about time travel.

Something I would be interested in seeing is a “horror monster movie” scenario structure, something along the lines of the first Alien movie or The Thing or Dracula. Something where the PCs are going up against a monster which 1) is impossible to defeat via standard combat mechanics, whether because it is simply far more powerful than the PCs, because its nature renders standard weaponry ineffective, or both; 2) has unusual abilities and weaknesses that the PCs do not initially know, and which they must discover and exploit in order to have a chance against it. Would love to see what you do with that.

@36 Vincent Maucorps says: How about a challenge about time travel ?

Viola!

https://strangeflight.blog/2016/06/14/time-travel-for-role-playing-games-the-basics/

@DanDare, that’s awesome.

I have just been reading the Kickstarter preview draft of Jeremy Strandberg’s Stonetop, and it strikes me that, in the terms of Justin’s post above, he has created a new scenario structure for Journeying, with his Chart a Course rules and attached GM advice.

He’s published an incomplete draft of the whole game for Kickstarter backers at this point and I’m really talking about the whole 44-page chapter on Expeditions that’s included there, but this public post gives enough to give a fair idea of the scenario structure, I think.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1735046512/stonetop/posts/3139924

The real heart is this:

“Chart a Course. When you wish to travel to a distant place, name or describe your destination (“Gordin’s Delve,” “the hagr’s lair,” or “wherever these tracks lead”). If the route is unclear, tell the GM how you intend to reach it. The GM will then tell you what’s required, the risks, and how long it will likely take.

When you set out on the journey, the GM will present each of the challenges one at a time—plus any surprises that you couldn’t have seen coming—in whatever order makes the most sense. Address them all and reach your destination.”

Then, the scenario structure:

“1) Establish the situation: they’re either on a leg of travel, or they’ve arrived at a point of interest. Describe the environment, provide details, ask questions, portray characters, etc.

2) Make a soft GM move, especially an exploration move (see page XX). Maybe your move introduces one of the challenges from Chart a Course.

3) Ask “What do you do?” or otherwise figure out what they’re up to.

4) Resolve their actions. If they trigger a player move, do what it says (and see the expedition moves, starting on page XX). If they roll a 6- or ignore a threat, make a hard GM move. Otherwise, say what happens.

5) Repeat. Continue to update the situation, make soft GM moves, ask what they do, and resolve their actions until there’s nothing interesting left to say or do in the current situation. Then, transition to the next leg of travel or the next point of interest.”

And many pages of examples and commentary about how to run this structure at the table. It’s brilliant.

https://lampblack-and-brimstone.com ➔ Stonetop

One scenario structure I’d be interested in is the “What Did We Do Last Night” style mystery, where a big part of the mystery includes the actions of the PCs. Examples include the Hangover movies and the How I Met Your Mother episode “The Pineapple Incident”. Obviously, after the PCs wake up sober, it’s just a standard mystery, but getting to that point would take some work to keep things feeling in-character. You’d need some way of getting player input for their actions while keeping information about the context of their actions away from them, as well as some way of ensuring they have a good reason to find out what they forgot.

Since you’ve re-posted this, here is a staple of storytelling that I think is very difficult to pull off in a TTRPG:

The party is brought low, defeated, and must fight their way back to defeat their foes.

No railroading, a convincing defeat that does not make the players mad, clear opportunities to rally back, etc. This is HARD in a game based upon player agency.

@TRay: It’s not hard if (a) you allow combat defeat to end with unconsciousness instead of death, and (b) you make it clear to the players that fights have a range of difficulty, you aren’t going to guarantee they’re all winnable, and it’s their job to avoid or escape when they’re overmatched.

You still can’t assure that any *particular* fight will end with defeat for them to rally from, because you still have to give them a fair chance to dodge it or escape, but sooner or later it will happen. The more stubborn they are about refusing to recognize defeat, the quicker it will be.

I’m rereading this old post, and I’m wondering: what would you call the improv-heavy structure most found in PbtA games such as Dungeon World:

– Prepare a hook, some settings elements (moods, location descriptors, a NPC or two)

– Prepare fronts (essentially a clock describing a threat)

– Do not prepare a story outline or end

– Let the dice inform the story through the “failure/partial success/success” resolution states

This clearly isn’t railroading, it’s not dungeon crawling (although it may happen in a dungeon), it’s narrative driven… I find that this is quite an important structure for many games and in particular in the solo-world it’s one that’s often super-imposed to regular games with things like the Mythic Emulator. It’s good to teach new GMs to “think on their feet” and enable low-prep games so it has a purpose as well.

What would that structure be named?

@piou

I think it might be useful to distinguish a ‘system structure’ or ‘campaign structure’, like the one you described for Dungeon World there, and a scenario structure, which is more focused – it doesn’t describe how a given rulebook or campaign is going to play, but rather a (specific way of) prepping, envisioning and providing meaningful choices for a general kind of situation PCs might find themselves in.

The structure you described for DW seems like it would try to resolve every possible scenario structure (the thing the hook should point to) the same way, which seems really weird to me. Having only played other PbtA games but not DW, I would not collapse every possible scenario to a simple clock.

One issue I’ve had with this series of articles (which are immensely useful and exciting, don’t get me wrong!) is that Justin generally describes scenario structures as something of a “one given thing” type deal. But I think it would be better to consider that it might be possible to approach many of them in different ways, so no one size fits all solution exists.

I say this because I think it would be useful to contextualize our discussions of scenario/campaign structures not in terms of “I’ve found the way to do it” but rather as “Here’s one way of doing it, and what about it worked for me”

Having said that, for people wondering about chases, I’ll give some of my thoughts:

1. I wouldn’t personally try to resolve “overland tracking” and “franctic, direct interaction chase” with the same system. I don’t think they have too much in common with regard to the general actions and pacing; overland tracking seems closer to a mystery (“where are they headed?”) mixed with “point A to B journey”

2. I have run chases using a very basic “sequence of obstacles/opportunities” to pretty decent success! You set up a line with nodes and define the starting distance between chaser and chasee in terms of these nodes. Each node frames a specific “mini-scene” when the chasees or the chasers reach them, which is about surpassing or taking advantage of the situation the node describes. Relate this to whatever system of movement/initiative/counting rounds that makes sense in the system you’re using, or just define a turn taking order of your own.

3. Define the parameters that will result on an end to the chase: is it enough to reach the chasee, or do you have to restrain them too? Do you escape the chaser as soon as you put X number of nodes between you and them? Or does doing that just give you an opportunity to roll some sort of stealth before losing them for good? Or do you have to reach a specific destination (i.e., the last node in our chain)?

4. One previous commenter was bothered by the fact that the implementation he came across of this method were just obstacles with specific skill checks suggested/demanded by it – the solution, then, is obviously to simply remove the assumption of a specific skill being used to resolve it and just present the obstacle (or, more generally, the in-fiction situation that requires some sort of choice) by itself! You wait for the player to state his intended action as a response to that decision point, only then do you ask them to roll anything, if at all necessary.

5. The reason I talk about obstacles/opportunities is so the PCs have a chance to be proactive when they are the chasees. An opportunity represents a chance to do something that might slow the chasers down. Since every opportunity for an NPC chasee just translates into a obstacle for the PCs, I wouldn’t bother framing them as ‘opportunities’ for the NPC but rather straight away as obstacles for the PCs (unless the NPC’s capacity to create the obstacle would be so uncertain that I felt I had to roll for it)

6. Another point of interest when thinking of scenario structures in general, I think, is thinking about whether or not your implementation of it is constraining what approaches the PCs can take to navigate it or not. One easy way to make a chase become boring, for instance, is only putting up obstacles that can be overcome by a few different skills (usually stuff like athletics and the like). If every obstacle is just “a chasm” or “a fence”, things will get boring quickly. So, as a GM principle, I would say that you should try to envision how different character specialities could come up during a chase, and create obstacles that would let the players use them. Note that this is different from going back to the issue of giving/asking a specific way of overcoming each obstacle – you won’t demand that they use the solution you thought up. You just used this line of thinking to create a broader set of possible obstacles to make the scenario more interesting.

7. There’s a lot more you can do to refine this structure (adding branching node paths, creating rules for quick catch-and-breakaway mini-fights that happen during the chase, rules for using ranged attacks during the chase, etc.), but that is best resolved case-by-case, and this comment is long enough

Hello, Justin! I really wonder of your notes, they are so helpful and useful for my GM preparing. Thank you so mush. I’ve been thought along about one of scenario structure, so may be you can help me with it. It’s a “road movie” scenario from point A to point B. I think it is a very useful scenario structure, a lot of dnd campaigns include journeys from one city to another, but there is no scenario structure, just a random encounters or railway with “thugs in an ambush”. I read your “pointclaw” note, but I don’t think it is the best way we can run it. Maybe you already had a note for it, so can anybody give me the link or maybe some reflection?

@Tony S: Check out Thinking About Wilderness Travel, specifically the stuff about routes.

This is also something I dive into in So You Want To Be a Game Master.

A true road trip-style movie would also be about the interactions between the characters on the trip. Use the social event scenario structure, treating the whole trip as the social event. For a dynamic and complex example of this in practice, check out the “Battle of the Bands” adventure in Welcome to the Island.