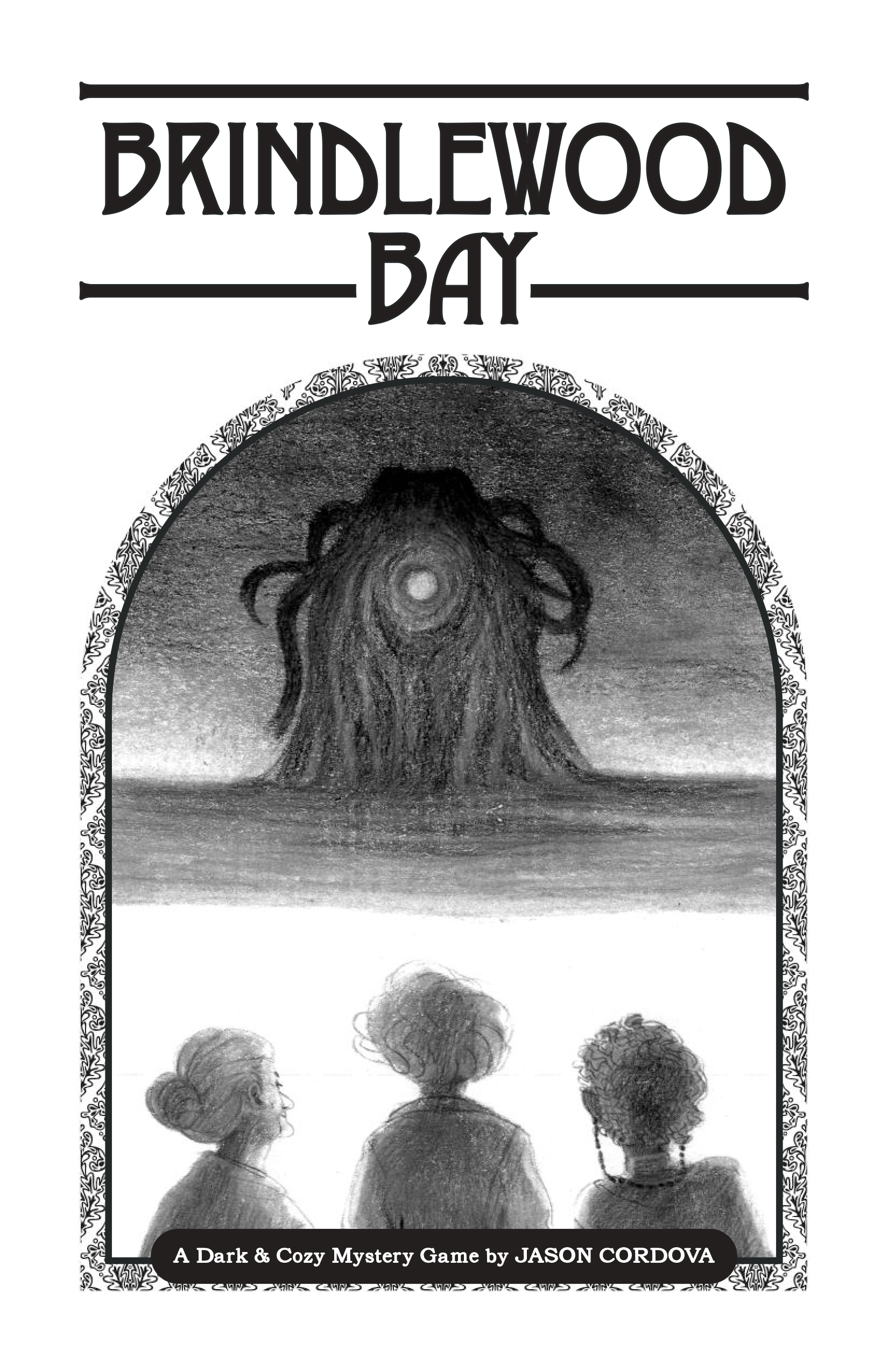

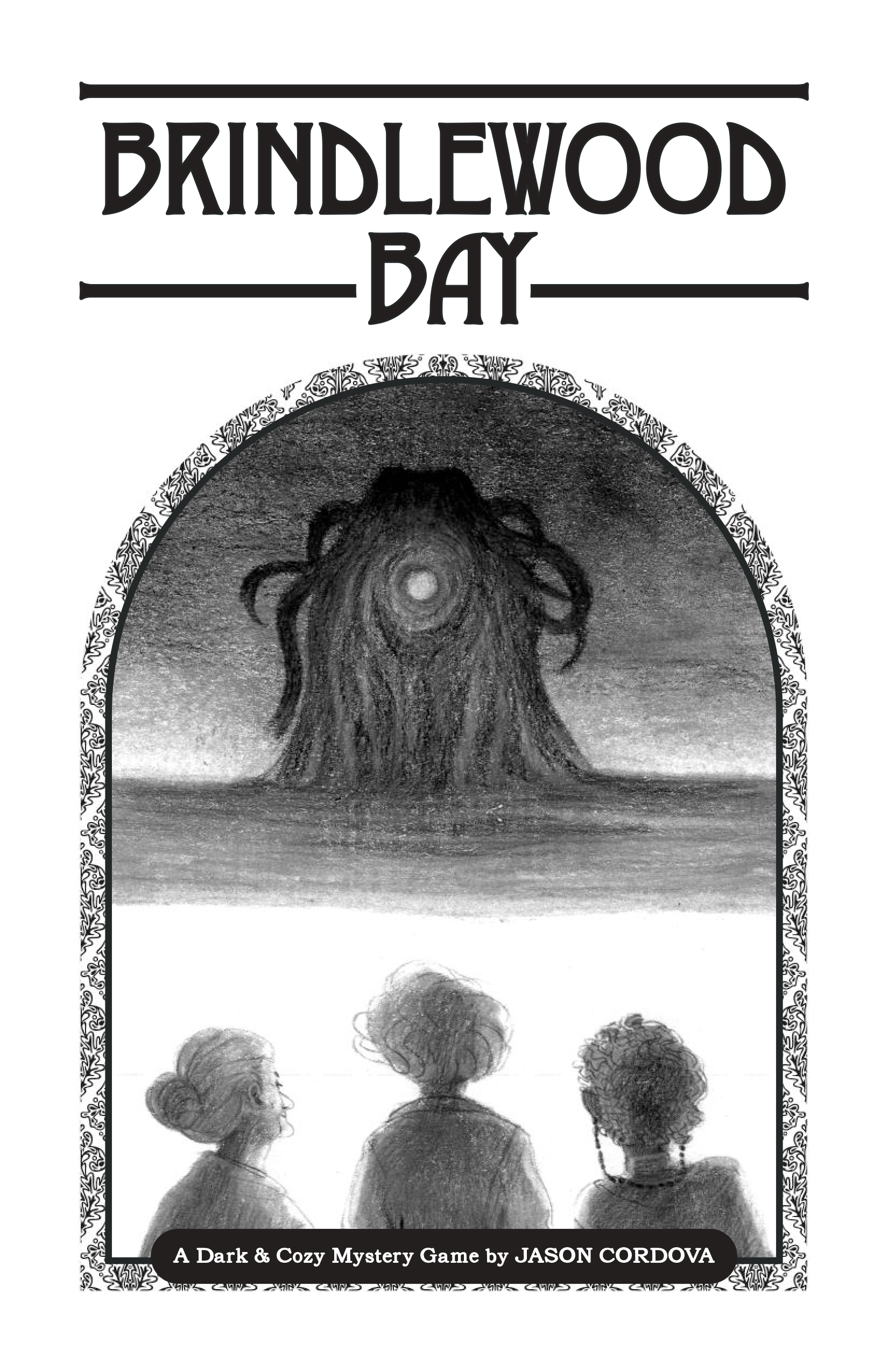

Brindlewood Bay is a storytelling game by Jason Cordova. The players take on the roles of the Murder Mavens mystery book club in the titular town of Brindlewood Bay. The elderly women of the book club, who are huge fans of the Gold Crown Mysteries by Robin Masterson starring the feisty super-sleuth Amanda Delacourt, somehow keep finding themselves tangled up with local murder mysteries in real life.

Brindlewood Bay is a storytelling game by Jason Cordova. The players take on the roles of the Murder Mavens mystery book club in the titular town of Brindlewood Bay. The elderly women of the book club, who are huge fans of the Gold Crown Mysteries by Robin Masterson starring the feisty super-sleuth Amanda Delacourt, somehow keep finding themselves tangled up with local murder mysteries in real life.

And there are a disturbing number of murders per capita in this sleepy little vacation town.

The reason there are so many murders here are the Midwives of the Fragrant Void, cultists who worship the “chthonic monstrosities that will usher in the End of All Things.”

That’s right. We’re mashing up Murder She Wrote with Lovecraft, along with a healthy dose of other mystery TV shows from the ‘70s and ‘80s (including Remington Steel, Magnum P.I., and even Knight Rider).

Brindlewood Bay sets things up with a fast, elegant character creation system that lets you quickly customize your Maven, sketch in their background, forge connections with the other PCs, and flesh out the group’s personal version of the Murder Mavens. Then it wraps the game around a Powered By the Apocalypse-style resolution mechanic, performing evocative moves by rolling 2d6 + an ability modifier with three result tiers (miss, partial success, success). To this now familiar mix, it adds a couple mechanical wrinkles:

- An advantage/disadvantage system tuned for the 2d6 mechanic; and

- Crown moves, which allow you to override the results of a die roll by either playing out a flashback scene (developing and deepening your character) or advancing your character’s connection to the dark forces in Brindlewood Bay, moving them inexorably towards retirement.

The Crown moves, in particular, seem to work very well in play, with the former building organically on the sketchy foundation established during character creation and the latter relentlessly advancing the dark, long-term themes of the game.

Brindlewood Bay’s real claim to fame, however, is its approach to scenario design. It comes bundled with five one-sheet scenarios (and provides guidelines for creating your own), but these notably do not include the solution to the mystery. In fact, there is no solution until it is discovered (created) in play.

Instead, each scenario presents:

- An initial scenario hook that presents the murder,

- A cast of evocative suspects,

- Several locations, and

- A list of evocative clues.

Examples of these clues include:

- An old reel of film showing a debauched Hollywood party.

- A bloody rug.

- A phone message delivered to the wrong number.

- A fancy car, the brake lines cut.

And so forth. There’ll be something like two dozen of these clues for each scenario.

The idea is that the PCs will investigate, performing investigation moves that will result in the GM giving them clues from this list. Then, Rorschach-like, the Mavens will slowly begin figuring out what these clues mean.

So how do you know what the solution actually is?

This is actually mechanically determined. When the Mavens huddle up, compare notes, and come up with an explanation for what happened, they perform the Theorize move:

When the Mavens have an open, freewheeling discussion about the solution to a mystery based on the clues they have uncovered — and reach a concensus — roll [2d6] plus the number of Clues found … minus the mystery’s complexity.

On a 10+, it’s the correct solution. The Keeper will provide an opportunity to take down the culprit or otherwise save the day.

On a 7-9, it’s the correct solution, but the Keeper will either add an unwelcome complication to the solution itself, or present a complicated or dangerous opportunity to take down the culprit and save the day.

On a 6-, the solution is incorrect, and the Keeper reacts.

When it comes to roleplaying games, I’m generally pretty skeptical of the “have the solution be whatever the players think it should be” GMing method. I mention this for the sake of others who share this opinion, because within the specific structure of Brindlewood Bay as a storytelling game it works great.

One key thing here is that the players must know what’s going on here: That the clues have no inherent meaning, that they are assigning meaning creatively as players (not deductively as detectives), and that the truth value of their theory is mechanically determined. I’ve spoken to some GMs who tried to hide this structure from their players and their games imploded.

Which, based on my experience playing Brindlewood Bay, makes complete sense. The game is entirely built around you and the players collaborating together to create meaning out of a procedural content generator stocked with evocative content. (If you’re looking for an analogy, Brindlewood Bay turns the GM’s creative process when interpreting a random wandering encounter roll into the core gameplay.) If the players aren’t onboard with this (for whatever reason), it’s going to be grit in this game’s gears.

But if everyone is on the same page, then the results can be pretty memorable.

For example, in my playtest of the game the players created a really great theory for how the circumstances of the murder came to pass. Then, on a roll of 8 for their Theorize move, I twisted the revelation of who was actually responsible for the death itself in such a way that the Mavens all collectively agreed that they needed to cover up the crime. Simply fantastic storytelling and roleplaying.

There are a couple niggling things about the game that I think merit mention.

First, instead of having the first scenario of the game be the Maven’s first murder mystery, the game instead assumes they’ve been doing this for awhile. (Sort of as if you’re joining the story in the middle of the first season, or maybe even for the Season 2 premiere.) There are kind of two missed opportunities here, I think.

On the one hand, the story of that “first Maven mystery” seems pretty interesting and everyone at my table was surprised we weren’t going to play through it. On the other hand, having posited that the Mavens have already solved several mysteries together, the game doesn’t leverage that during character creation. (By contrast, for example, the Dresden Files Roleplaying Game from Evil Hat Productions assumes the PCs have prior stories in common, but builds specific steps into character creation in order to collaboratively establish those events and tie the characters together through them.)

Second, I struggled to some extent running Brindlewood Bay because the game’s structure requires that the clues be presented in a fairly vague fashion. (This is explicitly called out in the text several times, and is quite correct. Like the rest of the group, the GM doesn’t know what the true solution of the mystery is until the Theorize move mechanically determines it. So the GM has to be careful not to push a specific solution as they present the clues.) The difficulty, for me, is that I think clues are most interesting in their specificity. And, for similar reasons, both I and the players found it frustrating when their natural instincts as “detectives” was to investigate and analyze the clues they found for more information… except, of course, there is no additional information to be found.

The other problem I had as the GM is that the Rorschach test on which Brindlewood Bay is built fundamentally works. Which means, as the story plays out, that I, too, am evolving a personal belief in what happened. But, unlike the players, I have no mechanism by which to express that belief, except by pushing that theory through the clues and, as we’ve just discussed, breaking the game. It was frustrating to be part of a creative exercise designed to prompt these creative ideas, but to then be blocked from sharing them.

These are problems I’ll be reflecting on when I revisit Brindlewood Bay. Which is a trip I’ll definitely be taking, because the overall experience is utterly charming and greatly entertaining. I recommend that you book your own tickets at your earliest opportunity.

Style: 3

Substance: 4

Author: Jason Cordova

Publisher: The Gauntlet

Price: $10.00 (PDF)

Page Count: 40+

BUY NOW!