Session 16A: To Labyrinth’s End

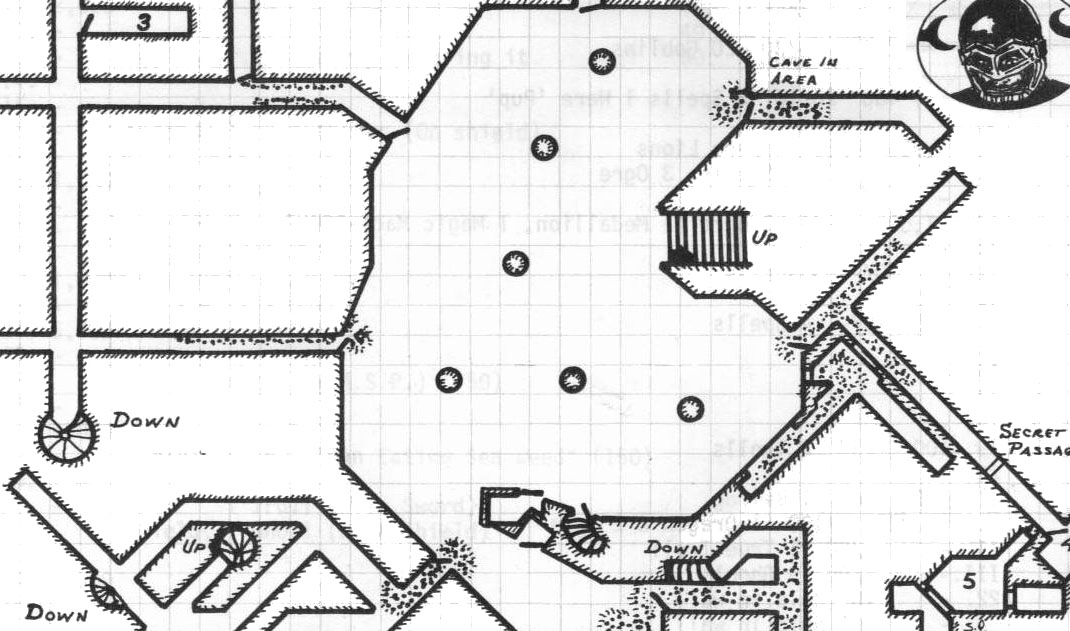

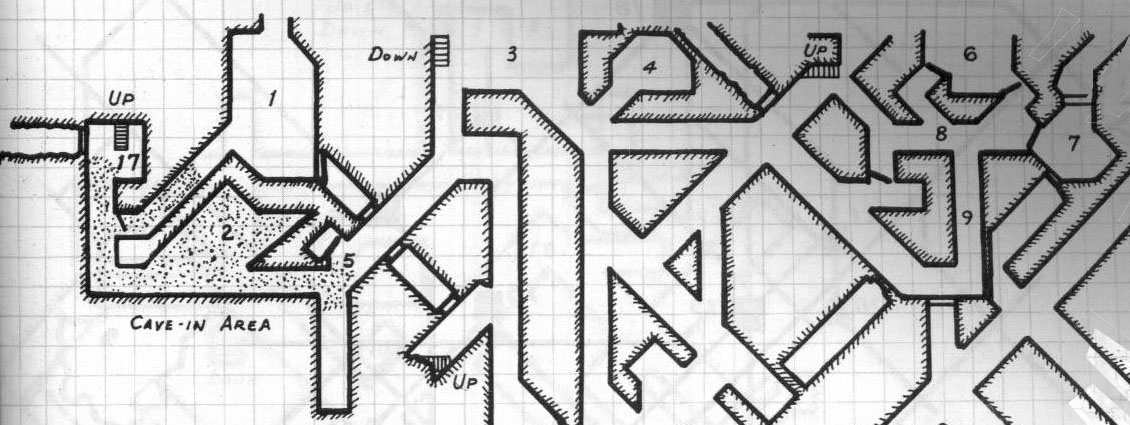

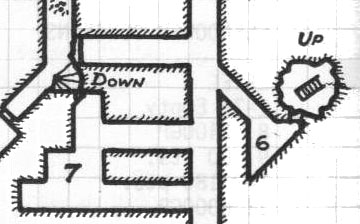

There was another hall directly opposite the one they had emerged from, but they could see that it ended in a complete collapse after only a few dozen feet. (A careful examination of Ranthir’s maps suggested that this was part of the same collapse that had blocked their progress on the upper level.

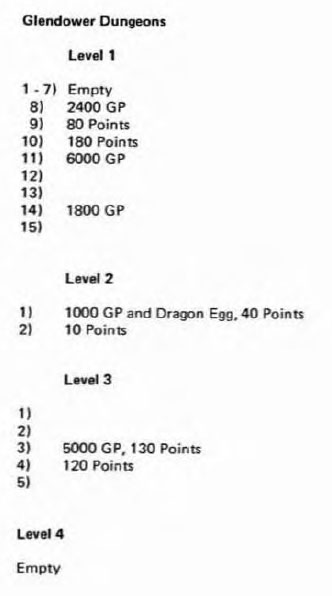

In the Laboratory of the Beast I use collapsed tunnels primarily to create an illusion of scale. Although this particular complex was already quite large (comprising 60+ rooms), I wanted to give the impression that it had originally been even larger. So I simply collapsed part of the complex.

There are a couple techniques that I think help to sell this illusion:

First, the complex needs to already have some scale to it. I’ve found that if you just map two or three rooms and then collapse a tunnel that supposedly leads to a vast complex that no longer exists, the players don’t really feel it.

Second, include smaller collapses that the players can discover the other side of (by circling around). The fact that stuff exists behind this collapse will reinforce the illusion that there were vast chambers behind all of those other collapses, too.

A brief digression here: Why did I decide 60+ rooms was enough and then evoked the rest of the complex by collapsing corridors?

Simple: I ran out of ideas.

When I sat down to design the Laboratory of the Beast, I brainstormed a bunch of ideas, reviewed the original brainstorming notes I had compiled when starting the campaign, and did a quick survey through some bestiaries for cool stuff I could include. Then I started mapping, jotting down which ideas went into which rooms as I went. Along the way I discovered some new ideas, and other stuff got thrown out when I discovered I didn’t actually like it or that it didn’t fit with how the rest of the complex was developing.

And then, somewhere down on the second level, my list of ideas had dwindled to almost nothing. So I collapsed the remaining tunnels. Then I went back up to the first floor and tweaked the map so that the collapse extended vertically, too.

WHY?

From a design standpoint, the primary reason to use this technique is when a particular dungeon concept requires a certain scale – “vast dwarven city”, “sprawling military laboratory”, “petrified remains of a demon so large its veins are corridors” – but in actual practice you’re not interested in spending the time necessary to explore the entirety of that scale.

This can also be true in a fractal sense: This complex should have had barracks for 500 men. It’s not difficult to map that, but searching 500 nondescript beds is boring, so drop a ceiling on most of the barracks complex and call it a day: The PCs will still be able to get a sense for how the dungeon functioned (“I guess these were the barracks”), but you bypass potential drudgery.

In general, collapsed tunnels also suggest age and imply danger. They can also create a sense of mystery. (And sometimes that mystery will be paid off if a collapse can be navigated or circumnavigated.)

In the dungeons of Castle Blackmoor, Dave Arneson used collapses in order to change the topography of the dungeon itself, thus altering the tactical and strategic properties of the megadungeon. Perhaps most easily used in campaign structures where the PCs are repeatedly re-engaging with the same dungeon complex, it’s also possible to sparingly use this gimmick by collapsing tunnels while the PCs are still inside the dungeon. In addition to the immediate peril of the collapse itself, the PCs will be posed with a new challenge as they try to figure out how to get back out of the dungeon. (There’s a scenario by JD Wiker in Dungeon #83 called “Depths of Rage” which uses this gimmick and which I ran to great effect in my first 3rd Edition campaign.)

Collapses can also open passages that didn’t previously exist. And, in either capacity, they can serve as triggers: The dark dwarves who are invading the outer dwarven settlements because their own realms have been destroyed by a cataclysm. The breaching of an ancient eldritch prison. Deep goblins finding new pathways to the surface. And so forth.

AND WHAT IF?

One thing to be aware of when using collapsed tunnels is the possibility that the PCs will figure out how to excavate or bypass them. (This becomes particularly true as they reach higher levels and gain access to magical resources that can make this task increasingly trivial.)

It can be useful, therefore, to have some sense of what’s “back there” behind the collapse, just in case your players make it necessary for you to know. This is probably just good design advice in general, honestly, and you can see that with the examples above: I knew that there were more beast-themed laboratories beyond the collapses. When we dropped the ceilings on the barracks, we knew that they were barracks. These complexes weren’t just random assemblies of randomness; they were built (and inhabited) with purpose, and if you understand that purpose then you’ll just naturally know what’s behind the collapse.

Thinking about this too much, of course, is a trap. The odds of the PCs deciding to clear some random collapse are actually quite low, so going into any sort of detailed prep about what’s back there is almost certainly wasted prep and should be avoided. (It also likely negates the entire reason you collapsed those tunnels in the first place; i.e., to avoid prepping that stuff.)

BUT WAIT!

What if you want the PCs to excavate a tunnel and find a bunch of cool stuff behind it?

This can be tricky to reliably pull off. The natural reaction most people will have to seeing a blockade of solid stone is to go somewhere else. Most players will also be guided by the meta-knowledge that dungeon collapses rarely have anything mapped behind them, so the hard work of clearing all that rock is likely to be met with the GM literally stonewalling them.

(Pun intended.)

In order to overcome that natural and cultivated aversion, you’ll need to turn the area beyond the collapse into an attractor: You need to create a specific desire/need for the PCs to clear the collapse. For this, you’ll want to employ the Three Clue Rule: Old maps depicting the area beyond the collapse. Withered undead who murmur about lost riches. And so forth. Maybe it will become clear that whatever brought the PCs to the dungeon in the first place must lie beyond the collapse.

Get digging!