Hillfolk includes some brief notes on how to decouple the DramaSystem and use the entire thing as a cap system, using a traditional roleplaying game of your choice to resolve procedural scenes while using the DramaSystem as a storytelling game for resolving dramatic scenes. I haven’t had a chance to try that yet myself, although it sounds potentially interesting. One of the things that caught my interest when reading through the DramaSystem, however, was the way in which its character creation procedure was capable of creating a group of PCs rich with dramatic potential, relationships, and tension.

And I also noted how easy it would be to strip that process down and streamline it into a generic core that you could use with any RPG (and most STGs) without using anything else from the DramaSystem. So even if the DramaSystem holds absolutely no interest for you, I think you’ll find this potentially very useful.

STEP 1: ROLE IN THE GROUP

Each player defines a role for their PC in the group. Some roles will be defined by their responsibilities; others may be defined in their relationship (familial or otherwise) to the characters holding those roles. Don’t shy away from setting a clear chain of command: Roleplayers often avoid doing that, but the tensions within a well-defined chain of command is a rich source for dramatic play. (Bear in mind that chains of command don’t necessarily need to be linear: Different characters can have ultimate power over different spheres of influence. For the excitement that can generate, study the history of the USSR’s Politburo.)

STEP 2: DEFINE RELATIONSHIPS

In reverse order, each player defines the relationship between their PC and another PC.

When you define your relationship to another PC, you establish a crucial fact about both characters. You can make it any kind of relationship, so long as it’s an important one. Family relationships are the easiest to think of and may prove richest in play. Close friendships also work. By choosing a friendship, you’re establishing that the relationship is strong enough to create a powerful emotional bond between the two of you. Bonds of romantic love, past or present, may be strongest of all.

As in any strong drama, your most important relationships happen to be fraught with unresolved tension. These are the people your character looks to for emotional fulfillment. The struggle for this fulfillment drives your ongoing story.

Defining one relationship also determines others, based on what has already been decided.

Players may raise objections to relationship choices of other players that turn their PC into people they don’t want to play. When this occurs, the proposing player makes an alternate suggestion, negotiating with the other player until both are satisfied. If needed, the GM assists them in finding a choice that is interesting to the proposing player without imposing unduly on the other.

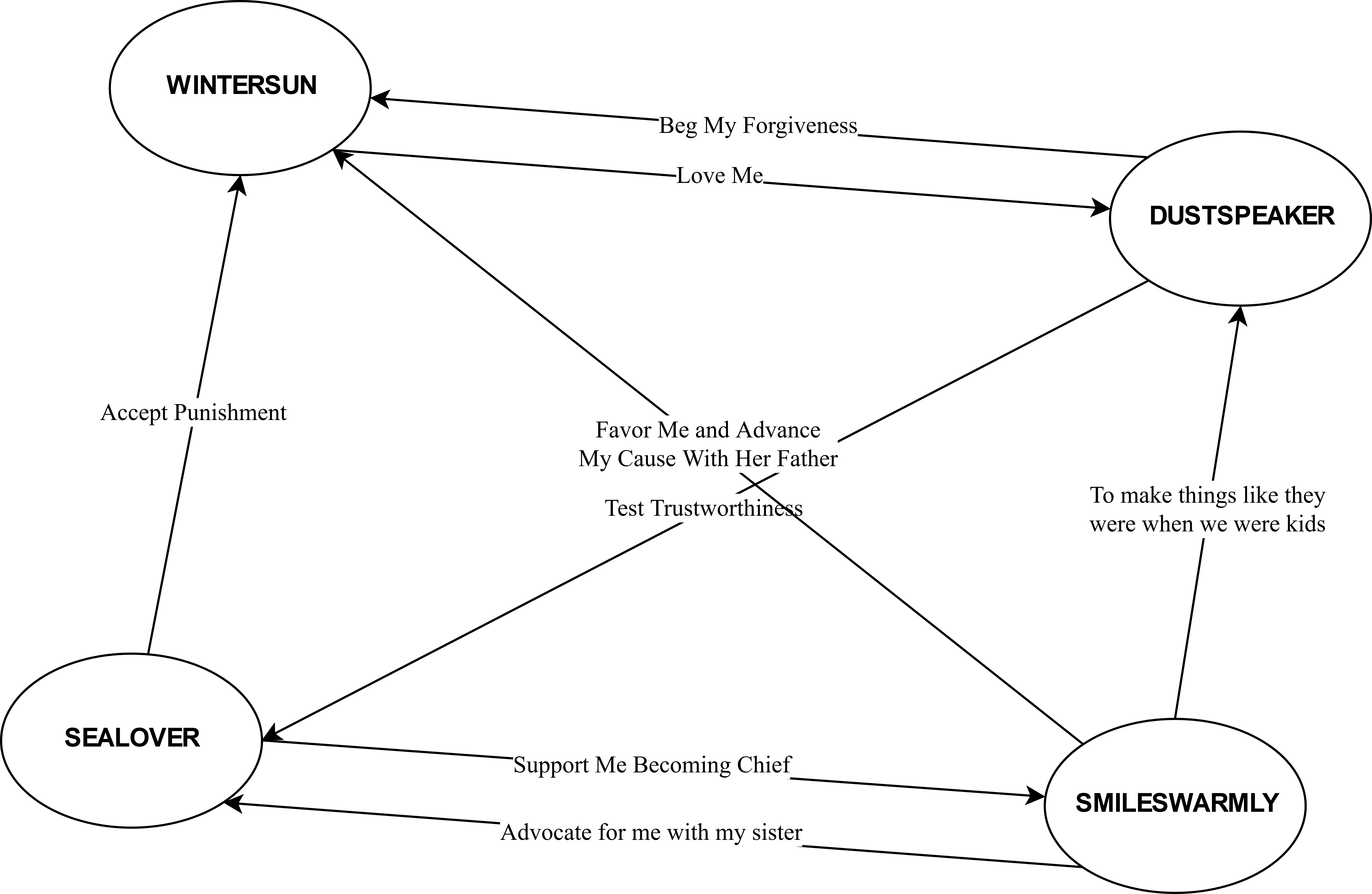

Keep track of relationships as they are established during character creation with a Relationship Map. Represent each character as a name with a box or circle around it. As relationships are defined, draw lines between the characters and label it with the nature of the relationship.

Repeat this process until each character has a relationship with every other character.

STEP 3: STATE DESIRE

A PC’s desire is the broadly stated, strong motivation driving their actions during dramatic scenes. The desire moves them to pursue an inner, emotional goal, which can only be achieved by engaging with other members of the main cast, and, to a lesser degree, with recurring characters run by the GM. Your desire might be seen as your character’s weakness: it makes them vulnerable to others, placing their happiness in their hands. Because this is a dramatic story, conflict with these central characters prevents them from easily or permanently satisfying their desire. Think of the desire as an emotional reward that your character seeks from others. The most powerful choices are generally the simplest:

- approval

- acceptance

- forgiveness

- respect

- love

- subservience

- reassurance

- power

- to punish

- to be punished

Note that these are emotional, not practical goals. If you find yourself drawn to a practical goal, delve past it to find the emotional need behind it. Veruca Salt, for example, craves material things in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but it’s because she’s desperately trying to elicit true affection from her father.

STEP 4: DEFINE DRAMATIC POLES

Driving any compelling dramatic character in any story form is an internal contradiction. The character is torn between two opposed dramatic poles. Each pole suggests a choice of identities for the character, each at war with the other. Events in the story pull the character from one pole to the next.

You’ll want to make both the poles and the conflict between them as clear as possible: In most dramatic scenes featuring your character, you, the GM, and the other players will want to play into this conflict, thus creating dramatic interest.

- Mark Thackeray (To Sir With Love): anger or civilisation?

- George Bailey (It’s a Wonderful Life): ambition or responsibility?

- Hamlet (Hamlet): justice or revenge?

- Joseph Cooper (Interstellar): adventure or family?

- Brian O’Conner (The Fast and the Furious): law or friendship?

STEP 5: WHAT YOU WANT FROM OTHERS

Finally, bring your dramatic poles into focus by declaring what they lead you to seek from particular other PCs.

In an order determined by the GM, each player declares what they want from another specific PC. Examples could include:

- love from the object of your affection

- approval from a mentor

- to punish your mother

The player of that character then defines why they can’t get it:

- “I could never love one of a lower caste.”

- “If I give you approval, you would stop trying.”

- “I will not be punished when I am blameless.”

If necessary, both players adjust the statement as needed to reflect the first character’s understanding of the situation. (Note that it is crucial that the PC cannot get what they want at the beginning of play. If the other player feels that their character would readily grant what the first PC is asking, then the stakes must be raised or changed.)

Repeat this process until all characters are named as the objects of at least two other characters’ wants. (Additional, unaddressed relationships may be defined or developed during play.

This material is covered under the Open Gaming License.

This seems like a much more in-depth version of Bonds from the Powered by the Apocalypse games, which is great because I love Bonds in those systems! As you may know, they also give you a bonus on rolling Aid/Hinder Other against someone you have Bonds with, making it so the people you know best are the people you can help and unintentionally harm the most.

Have you ever tried using Bonds from those systems?

Some feedback: I tried using it on my table! I’m a rather neophyte GM (5 years of

GMing but I learned to GM by myself — when, as another post of yours pointed out, no books nowadays teach you how to GM) so I’m prone to some errors, to which I meditate to remedy, and this is how I found your blog. I decided to make my first homebrew campaign a city-based political intrigue/supernatural mystery — I only knew how to “properly” run railroads and combat, so I noticed that to make a campaign anew, if I didn’t want a railroad, I needed to learn another structure and this is how I delved deep into the node-based structures which were really helpful to me.

Because of lack of experience errors both on my side and the players’, it ended up being a rather ardous task. Because just how I was learning how to give freedom to my players, many also had to learn how to be free for their first time (only one out of the five players had me as a GM before, but most also almost only played railroads). It was slow and painful in a sort of “Bumbling in Freeport” way.

So, how it went for us:

Case 1: I told everyone the basic scenario for the campaign. I said it would be a mystery game set in nation X, but not much else. I just told them to hold their horses until more information was given in order to make characters that made sense in the campaign, as the dramasystem is rather restrictive.

How it actually went: Two players immediately got excited with the new game and got married to their character ideas before they even met the rest of the party. “I’ll play this or not play at all” style. Sigh.

What I think I should have done: Honestly I think that was poor behavior on their part, but I understand the reason it happened. The new system had classes that fit things they always wanted to play as but couldn’t in other systems. I don’t think it will happen again with the same people, but next time I’ll make first a shorter game, but not so short they will walk out unfulfilled (~10 sessions should be fine).

Case 2: I said the players were free to decide which angle to tackle a “mystery campaign” with — whether they would be inquisitors from the clergy, generic lowbie adventurers, an evil cult, etc. was their choice. “Give me your ideas and I’ll GM it”.

Because I started roleplaying from systemless PbP settings, I was used to working together to decide our game with other players. I thought it was a simple affair and they would appreciate it.

How it went: They couldn’t do it and spinned in circles, waiting for me to say what the game would be. I didn’t.

What I think I should have done: This idea of freedom would have worked well on a party more experienced with this kind of thing. I hope to train this skill eventually. Next time I’ll pitch three or five different campaign ideas and let them pick one, with way more well-defined hooks.

Case 3: First step – role in the group.

How it went: Since two people made characters in all but the sheet already and the rest didn’t have a campaign prompt to follow whatsoever, they flocked around the two players who had a character concept, but not so much as I would have liked as four out of five picked classes independently. Since no one had a “party” concept, it was rather awkward. And since many people had already an independent idea of what their character could be, many people tried to pick redundant roles.

What I think I should have done: Defined a clear “party concept” instead of expecting my players to create one, as said in case 2. I would skip this part with another batch or first-timers to this subsystem, though.

Case 4: Second step – define relationships.

How it went: Ahahaha I still don’t believe we went past this part. Fortunately the three players that didn’t think out the entire character before the Discord server was even made were very lost, and in this “very flexible”. Still it was very hard to fit their characters and I had to suggest an entire character concept for one of them to make it work. I nerfed the requirement from “a bond with everyone” to “a bond with two other characters”.

What I think I should have done: It would really, really have been easier if I had defined a “party concept” from the start. It probably would’ve been wise to also skip this part with a bunch of newcomes however.

Case 5: Fourth and third step – state desire and dramatic poles.

How it went: Smoothly. Compared to the thunderstorm that were the previous two steps, everyone had those ready in a much shorter time. Since I didn’t need to, I gave no interference or suggestions.

What I think I should have done: Exactly what I did. THOSE two are what I’ll be reusing on all my next games. The game hasn’t started yet but they’re simple and brilliant.

Case 6: What you want from others.

How it went: It was somewhat easier than case 4 because those relationships were already made in the first place, but most people struggled (for the person I suggested a character concept for it was a breeze. They got *four* connections immediately). Still painful and eventually I dropped it when people couldn’t think of more than one connection for one of the players who had made their character concept before.

What I think I should have done: Like the first and second steps of this subsystem, only introduce them after people get used to the easier steps of the hillfolk modular subsystem.

—

TL;DR, my conclusions:

1. It works best if a clearly defined party concept is set. The players can come up with this themselves, but if they aren’t used to it, set one for them as the GM. Instead of being generic “mercenaries/adventurers/investigators”, say they are “special forces from the anti-brainwashing research group”, “spies hired by the Houstons”, “the city guard”, “lesser nobility knights in northern Westeros” and stick to that as your campaign concept.

2. For mathematical reasons, it’s easiest for a 2-4 players party than a 5+ party. My party had 5 players and I don’t plan on running 5-person parties ever again.

3. If it’s the first time running the party through this system and they never played on a “bonds” system with other players before, introduce this gradually in consecutive short games. Starting with only “state desire” and “dramatic poles” are good ideas.

4. The game hasn’t started, but I feel people care way more about others characters’ as a result of the subsystem itself. They already feel like a group even before session 1. Its results were positive but the path to them was painful, both because no one was used to do something like this and because I sucked at giving any guidance whatsoever.

And, not related to this, but since you already read all of that: Yes, my first time with node-based design was as ugly as a first breakup. I found myself not organizing properly shit at the first time, and had to redo the scenario from the scratch. On the second time I found myself internalizing a breadcrumb trail instead of a truly node-based scenario when I made a flowchart to visualize how my clues list was going, so I also threw it into the trash and started to make a third scenario. I’m still on the finishing touches of that one (will finish it while players fill out their sheets) but I think it’s workable — I doubt it’s perfect, but it’s way better than the first two ones.

Thanks for your writing, Alex. I would have been so, so lost without it. I frantically consumed this blog over the last month or two and realized that I knew nothing about GMing really.

Gatan@2: Having a campaign crash and burn is inevitable. You know you’re a real GM if that just leaves you planning, “Okay, so NEXT TIME…”

@colin r: Thanks for the kind words. In the end, I decided that this campaign was a mess not worth even starting.

Also, @Alex: This vid of the “I want it now!” scene you linked in the article has better resolution: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5wAlQf4WdiE