Of course, it’s all well and good to say, “Prep Situations.” But one of the reasons people prefer the plotted approach is that it provides a meaningful structure: It tells you where you’re going and it gives you a way to get there.

Without that kind of structure, it’s really easy for a gaming session to derail. It’s certainly not impossible to simply turn the PCs loose, roll with the punches, and end up somewhere interesting. Similarly, it’s quite possible to jump in a car, drive aimlessly for a few hours, and have a really exciting time of it.

But it’s often useful to have a map of the territory.

This line of thought, however, often leads to a false dilemma. The logic goes something like this:

(1) I want my players to have meaningful choice.

(2) I need to have a structure for my adventure.

(3) Therefore, I need to prepare for each choice the players might make.

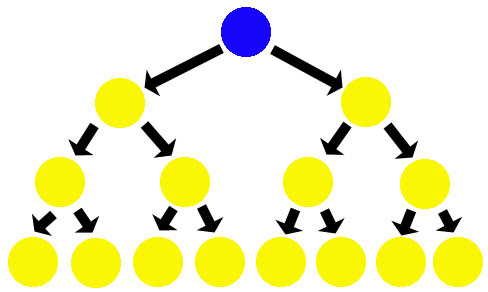

And the result is an exponentially expanding adventure path:

The problem with this design should be self-evident: You’re preparing 5 times as much material to supply the same amount of playing time. And most of the material you’re preparing will never be seen by the players.

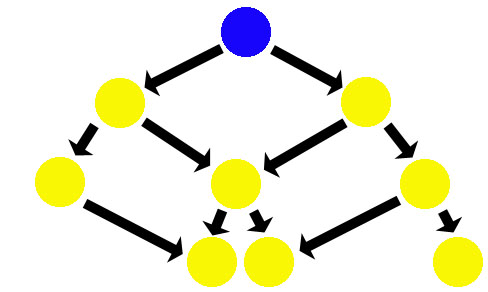

In some ways, of course, this is an extreme example. You could simplify your task by collapsing some of these forks into each other:

But even here you’re designing eight steps worth of material in order to provide three steps of actual play. You’re still specifically designing material that you know will never be used.

And in other ways it’s actually not that extreme at all: The original example assumes that there are only two potential choices at any given point on the path. In reality, it’s quite possible for there to be three or four or even more – and each additional choice adds a whole new series of contingencies that you need to account for.

Ultimately, this sort of “Choose Your Own Adventure” prep is a dead end: No matter how much you try to predict ahead of time, your players will still find options you never considered — forcing you back into the position of artificially constraining their choices to keep your prep intact and leaving you with the exact same problem you were trying to solve in the first place. And even if that wasn’t true, you’re still burdening yourself with an overwrought preparation process filled with unnecessary work.

The solution to this problem is node-based scenario design. And the root of that solution lies in the inversion of the Three Clue Rule.

I question the “You’re still specifically designing material that you know will never be used.”. If you create material for a specific game world, you might not use it now, but you can also use it later – in another adventure, in another situation. I’ve always found that the ideas gotten from creating these ‘side-paths’ are often very useful in fleshing out the game world.

Of course I don’t have time to game anymore because of this approach! 😉

-Michael,

I think that’s the point I (and thankfully at least one friend) have got to. We spend so much more time (and probably enjoy more) conceptually playing D&D by thinking up ‘oh, they could do this, they could do that’ or ‘I could play a ___ who does ___’, and etc that the playing just doesn’t get done, and for good reason. Playing is slow, you have to wait for everyone’s turn, and, the most fundamental flaw of D&D, you’re trying to get what’s nearly the most antisocial subset of society to sit in a room together.

Also there’s so many great roleplaying tips, blogs, videos, livestreams, editions, books, maps, online communities, that I can’t help but lose myself in them attempting to learn it all and accept no less.

Something we should be doing with all our designs – save those write-ups, sketches and designs! Label, tag and duplicate copies for your different rpgs and or later sessions. Your library or clearinghouse of stuff will help create new variations or originals.