Hillfolk includes some brief notes on how to decouple the DramaSystem and use the entire thing as a cap system, using a traditional roleplaying game of your choice to resolve procedural scenes while using the DramaSystem as a storytelling game for resolving dramatic scenes. I haven’t had a chance to try that yet myself, although it sounds potentially interesting. One of the things that caught my interest when reading through the DramaSystem, however, was the way in which its character creation procedure was capable of creating a group of PCs rich with dramatic potential, relationships, and tension.

And I also noted how easy it would be to strip that process down and streamline it into a generic core that you could use with any RPG (and most STGs) without using anything else from the DramaSystem. So even if the DramaSystem holds absolutely no interest for you, I think you’ll find this potentially very useful.

STEP 1: ROLE IN THE GROUP

Each player defines a role for their PC in the group. Some roles will be defined by their responsibilities; others may be defined in their relationship (familial or otherwise) to the characters holding those roles. Don’t shy away from setting a clear chain of command: Roleplayers often avoid doing that, but the tensions within a well-defined chain of command is a rich source for dramatic play. (Bear in mind that chains of command don’t necessarily need to be linear: Different characters can have ultimate power over different spheres of influence. For the excitement that can generate, study the history of the USSR’s Politburo.)

STEP 2: DEFINE RELATIONSHIPS

In reverse order, each player defines the relationship between their PC and another PC.

When you define your relationship to another PC, you establish a crucial fact about both characters. You can make it any kind of relationship, so long as it’s an important one. Family relationships are the easiest to think of and may prove richest in play. Close friendships also work. By choosing a friendship, you’re establishing that the relationship is strong enough to create a powerful emotional bond between the two of you. Bonds of romantic love, past or present, may be strongest of all.

As in any strong drama, your most important relationships happen to be fraught with unresolved tension. These are the people your character looks to for emotional fulfillment. The struggle for this fulfillment drives your ongoing story.

Defining one relationship also determines others, based on what has already been decided.

Players may raise objections to relationship choices of other players that turn their PC into people they don’t want to play. When this occurs, the proposing player makes an alternate suggestion, negotiating with the other player until both are satisfied. If needed, the GM assists them in finding a choice that is interesting to the proposing player without imposing unduly on the other.

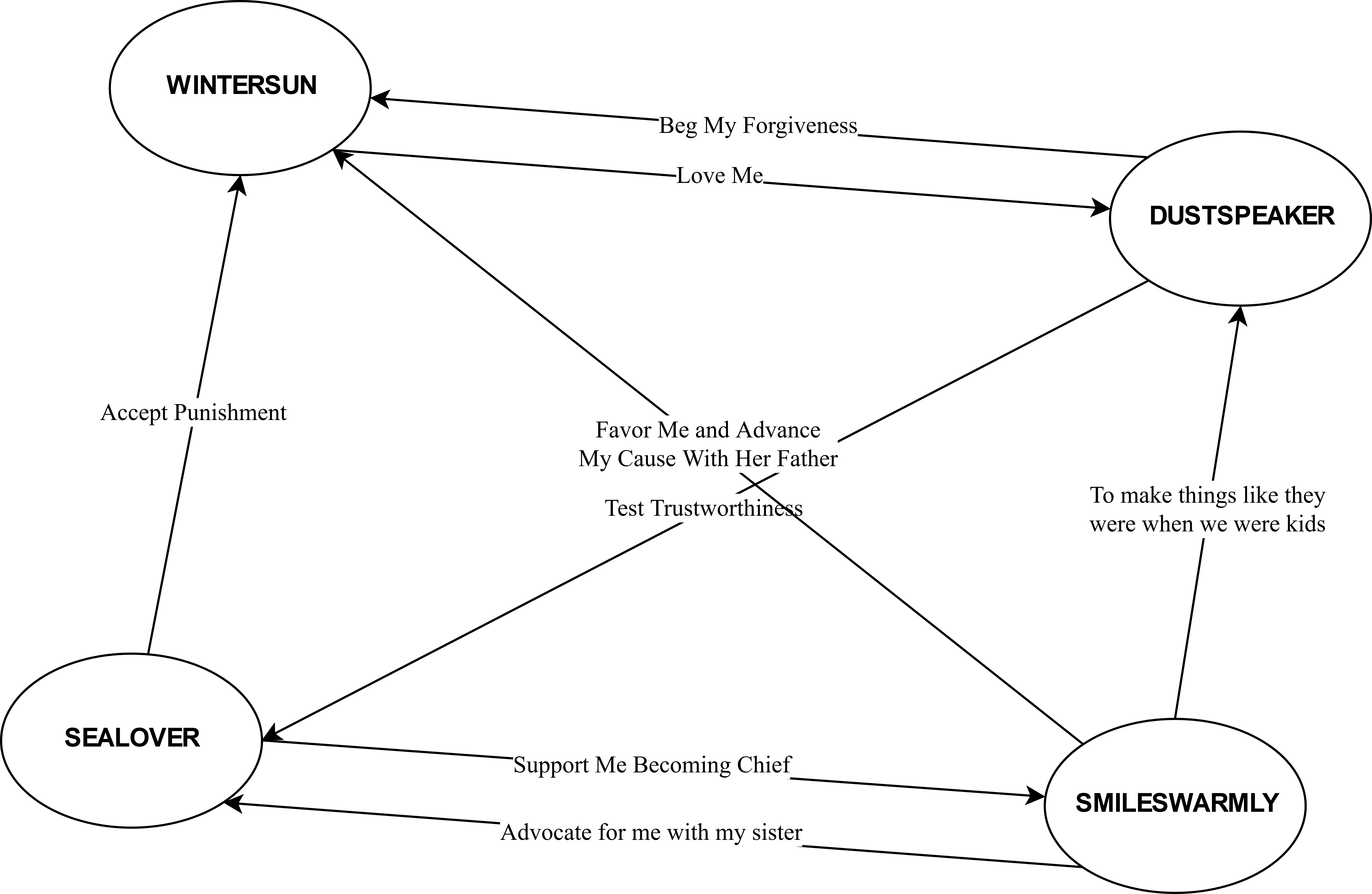

Keep track of relationships as they are established during character creation with a Relationship Map. Represent each character as a name with a box or circle around it. As relationships are defined, draw lines between the characters and label it with the nature of the relationship.

Repeat this process until each character has a relationship with every other character.

STEP 3: STATE DESIRE

A PC’s desire is the broadly stated, strong motivation driving their actions during dramatic scenes. The desire moves them to pursue an inner, emotional goal, which can only be achieved by engaging with other members of the main cast, and, to a lesser degree, with recurring characters run by the GM. Your desire might be seen as your character’s weakness: it makes them vulnerable to others, placing their happiness in their hands. Because this is a dramatic story, conflict with these central characters prevents them from easily or permanently satisfying their desire. Think of the desire as an emotional reward that your character seeks from others. The most powerful choices are generally the simplest:

- approval

- acceptance

- forgiveness

- respect

- love

- subservience

- reassurance

- power

- to punish

- to be punished

Note that these are emotional, not practical goals. If you find yourself drawn to a practical goal, delve past it to find the emotional need behind it. Veruca Salt, for example, craves material things in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but it’s because she’s desperately trying to elicit true affection from her father.

STEP 4: DEFINE DRAMATIC POLES

Driving any compelling dramatic character in any story form is an internal contradiction. The character is torn between two opposed dramatic poles. Each pole suggests a choice of identities for the character, each at war with the other. Events in the story pull the character from one pole to the next.

You’ll want to make both the poles and the conflict between them as clear as possible: In most dramatic scenes featuring your character, you, the GM, and the other players will want to play into this conflict, thus creating dramatic interest.

- Mark Thackeray (To Sir With Love): anger or civilisation?

- George Bailey (It’s a Wonderful Life): ambition or responsibility?

- Hamlet (Hamlet): justice or revenge?

- Joseph Cooper (Interstellar): adventure or family?

- Brian O’Conner (The Fast and the Furious): law or friendship?

STEP 5: WHAT YOU WANT FROM OTHERS

Finally, bring your dramatic poles into focus by declaring what they lead you to seek from particular other PCs.

In an order determined by the GM, each player declares what they want from another specific PC. Examples could include:

- love from the object of your affection

- approval from a mentor

- to punish your mother

The player of that character then defines why they can’t get it:

- “I could never love one of a lower caste.”

- “If I give you approval, you would stop trying.”

- “I will not be punished when I am blameless.”

If necessary, both players adjust the statement as needed to reflect the first character’s understanding of the situation. (Note that it is crucial that the PC cannot get what they want at the beginning of play. If the other player feels that their character would readily grant what the first PC is asking, then the stakes must be raised or changed.)

Repeat this process until all characters are named as the objects of at least two other characters’ wants. (Additional, unaddressed relationships may be defined or developed during play.

This material is covered under the Open Gaming License.