“If you were teaching a intro-level college class on roleplaying game design, what would be the reading list?”

Interesting question.

I’m going to design this as a survey/history course. And you’ll need to snag copies of these at the campus bookstore:

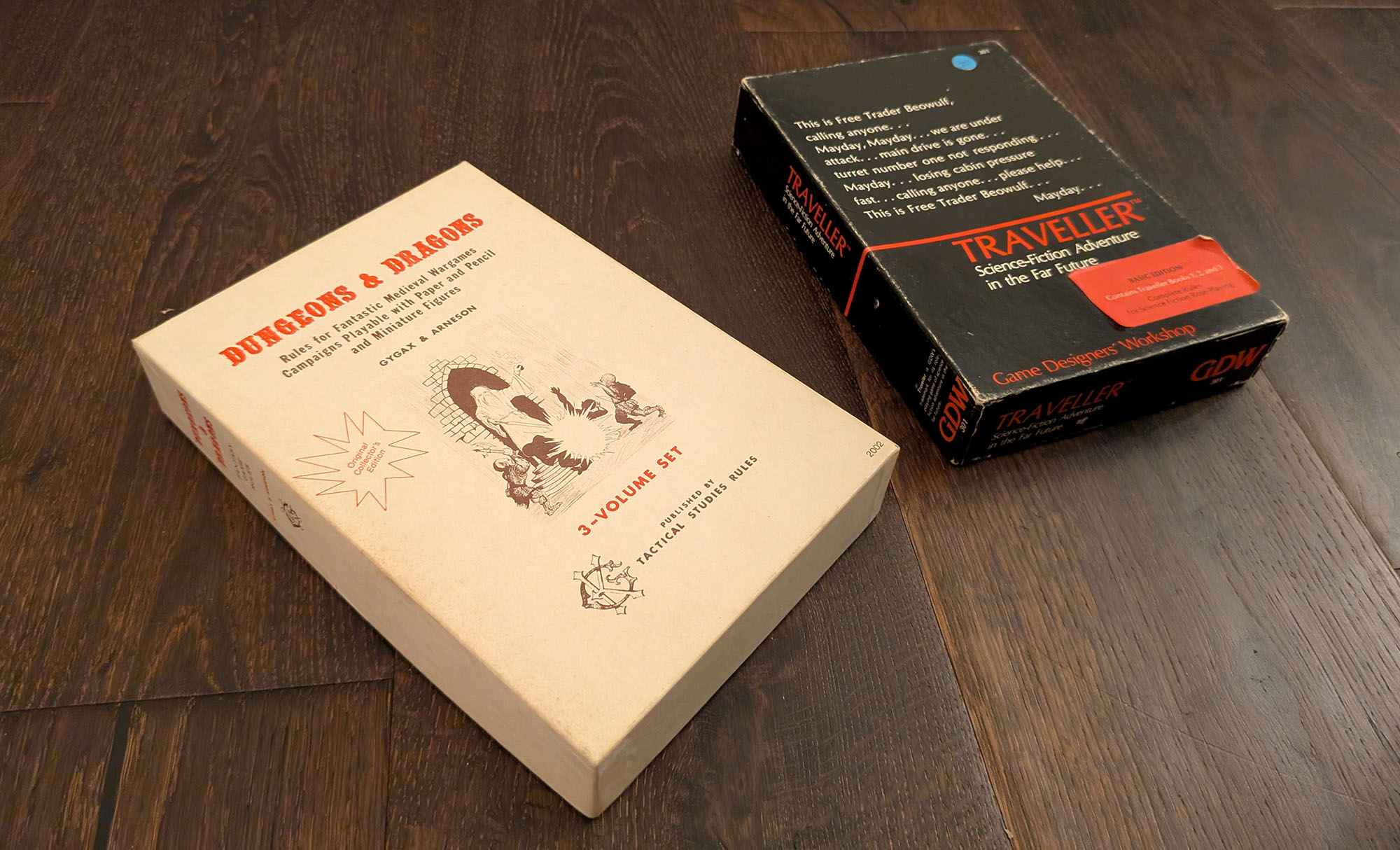

1974 D&D

Traveller

GURPS or Champions

Paranoia (1st Edition)

Vampire the Masquerade

Amber Diceless Roleplay

Burning Wheel

Apocalypse World

And we’ll wrap the course up by comparing D&D 3E, 4E, and 5E, with a particular focus on how they responded to design trends.

D&D 1974

This is the beginning. The baseline for everything that follows and a frame for discussing the proto-history and origin of RPGs from Kriegsspiels to David Wesley to Dave Arneson.

TRAVELLER (1977)

Traveller does triple duty for me.

- It gives insight into the first generation of RPGs that were responding to D&D.

- One of the first science fiction RPGs, after Starfaring and Metamorphosis Alpha.

- Includes a Lifepath system, giving us a first step in looking at different approaches to character creation.

GURPS / CHAMPIONS

(’80s Editions)

The birthplace of the well-supported generic/universal RPG system.

A central thesis of this class will be that RPGs pretty universally pushed for “accurate simulation” as a primary design goal through the late ‘70s and ‘80s. Whichever one of these games we choose to look at it will serve as a great exemplar of that trend.

It will also give us point-buy character creation in its fullest flower, allowing us to clearly show the difference between character generation in 1974 D&D and the character crafting which would come to largely dominate the hobby.

PARANOIA

(1st Edition)

This is kind of an oddball choice. Every intro class has one of these on the reading list, right?

But it’s here for a reason.

On the one hand, Paranoia is a comedy game, which gives us a nice, sharp look at the emerging diversification of creative agendas in the ‘80s.

On the other hand, it also examines the unexamined “simulation = good” trend in the ‘80s. Paranoia is a lighthearted comedy game, but its first edition features, among other things, a Byzantine three-tier skill specialization system, because “simulation = good” even if it made no sense for what the game was actually trying to achieve.

(I will give extra credit to any student arguing that the incredible minutia of the system was actually part of the satire of a Kafkaesque government bureaucracy. They’re wrong, but it shows they’re thinking critically about this.)

WHITHER THE UNIVERSAL SYSTEM?

Universal RPGs were VERY popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and then they weren’t. There are still some around today, of course, but the only truly popular ones are 20+ years old.

One theory is that the niche was definitively filled by GURPS, and no other universal RPG could ever compete with GURPS’ library of support material.

The other is that universal RPGs were at their strongest because of the “simulation = good” paradigm. Once you move past the idea, as demonstrated in Paranoia, that “good system” is a Platonic ideal divorced from a game’s creative agenda, the appeal of a “universal system” is not eliminated, but significantly diminished.

VAMPIRE: THE MASQUERADE

This brings us to Vampire: The Masquerade, a hugely important game that grappled mightily with the idea of pushing a creative agenda other than simulation.

The Storyteller system is interesting to analyze because (a) it ultimately fails to achieve its storytelling goal (and analyzing failure is a great way to learn) and (b) it’s virtually impossible to understand GNS theory without the context of Storyteller.

AMBER

Before we get to GNS, though, Amber Diceless Role-Playing will be our exemplar of the snap-back against detailed simulation.

Emphasized by its diceless engine, Amber was one of many early ‘90s games that were fed up with complexity and bounced to the opposite extreme. It’s an elegant tour de force for designing mechanics customized to the creative agenda and setting of the game.

Plus, Amber features alternative structures for organizing campaigns and extending player beyond the session. So we’re getting a lot of mileage from this one title.

BURNING WHEEL

There are a lot of Forge-era indie games we could choose to spotlight GNS theory. One could argue that we should go with a game by Ron Edwards or D. Vincent Baker. (We’ll cover the latter with Apocalypse World.)

Burning Wheel is, ultimately, just a better game and synthesizes a wider range of innovations. So that’s what I’m tapping.

APOCALYPSE WORLD

Which brings us to Apocalypse World.

Powered by the Apocalypse is the single biggest non-D&D influence on RPG design in the last fifteen years, so it’s basically essential. And, as I just mentioned, D. Vincent Baker is a seminal figure and his design philosophy should be highlighted. So this is another game that’s doing double duty.

WotC-ERA D&D

The big wrap-up for our course is a comparison of D&D 3E, 4E, and 5E.

D&D is, of course, the 10,000 lbs. gorilla in the RPG design room. If we’re teaching an intro course, we absolutely need to cover its evolution.

Post-1974, however, D&D has been extremely reactive in its design. It largely does not innovate, but its massive gravity means anything it refines is reflected back into the industry in a massively disproportionate way. (Take, for example, the concept of advantage/disadvantage as modeled by rolling twice and taking the better/worse result. This was an exceptionally obscure mechanic pre-2014, but after D&D 5E used it, you can find it everywhere.)

Having broadly covered the history of RPG design, therefore, looking at how D&D reacted to (or didn’t react to) those design trends is a great way to review and critically analyze everything we’ve learned in the course.

The final list also gives us (coincidentally, I didn’t actually plan this) wo games from each decade (‘70s through ‘10s) with an extra dollop of D&D. That’s a good gut-check to make sure I wasn’t getting too biased in my selections.

NOTABLE ABSENCES

There are a few notable things missing from this reading list.

FATE, which had a massive influence in the decade before Powered by the Apocalypse, serving as the system for any number of games.

Storytelling Games. Only peripherally looking at how STGs have influenced RPG design is iffy. You can easily make a case for throwing in Once Upon a Time or Microscope or Ten Candles.

RPGs in a Box. These are games like Arkham Horror, Gloomhaven, and Descent. They aren’t actually RPGs, but they’re in the same design space.

Starter Sets. There are unique design considerations in making an effective starter set, but we didn’t cover them at all.

Organization-based Play. This would be a game like Ars Magica, Blades in the Dark, or Pendragon. This has been a persistent design goal for RPGs since Day 1. I can touch on it a bit with Traveller, but it’s really exploded in the past decade and not having a more recent example is a limitation.

Call of Cthulhu. Just because it’s Call of Cthulhu. But my goal wasn’t Most Important RPGs (Call of Cthulhu is easily Top 5), it was Introduction to RPG Game Design. There’s stuff that I could use Call of Cthulhu to teach, but not enough hooks to knock others off this list.

After all, there are only so many hours in a semester.

FURTHER READING

It’s Time for a New RPG

A History of Stat Blocks

This is a very good list, but I would maybe argue that there are a few more notable absences: GMless RPGs (I would probably use Fiasco), solo RPGs (lots of options, take your pick), and choose-your-own-adventure gamebooks ala Fighting Fantasy (admittedly something of an oddball footnote in RPG history, but still significant enough to at least warrant a mention, especially in the UK from what I understand)

> (Take, for example, the concept of advantage/disadvantage as modeled by rolling twice and taking the better/worse result. This was an exceptionally obscure mechanic pre-2014, but after D&D 5E used it, you can find it everywhere.)

Is this true? Bonus and penalty dice are used in pretty big games like FATE and The Shadow of Yesterday; the D&D mechanic is just a special case of bonus/penalty dice where the initial dice pool is always a single d20.

VERY suprised at the snub of F.A.T.A.L.

Personally, I’d go a different route. The primary textbook would probably be “Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground” if I were doing a history-of-the-hobby unit.

Maybe one of the Peterson texts like Playing at the World, or Game Wizards.

Your list is a great short-form of the big names and how RPGs have evolved, but one of the major themes I’d want to impart on a designer is that they DON’T have to hew to DnD and responding to DnD.

On the other hand, it’d would be pretty fun to perform literary/design critiques of the white box. That thing is a mess.

Something that just occurred to me: Pick apart the whitebox and then compare it to OSR retroclones to see how they tried to fix the problems.

I would still want to take a bunch of time to talk about things other than DnD, but a before/after of OSR content’s iterations on the White Box’s designs would be a great jumping-off point for talking about the various goals of good design (clarity, teachability, pace-of-play, and design priorities). The OSR gives up a lot of stuff in the name of keeping things simple. How does that contrast with the maximalist approach of something like Pathfinder 2e or DnD 5e?

Great list! I really love your comments about Paranoia and Storyteller.

I feel like the comments above (5 at the time I write this) all make good points for material or topics to cover in higher level RPG design classes (yes, even F.A.T.A.L.). For an intro level class, I think you cover a good amount of varied design, and also the major eras of gaming.

Aw man, now I’m bummed I can’t actually take this class next semester

I would argue Chaosium’s BRP game system is the first stab at a universal game engine. The genres the system has been put to make good with are numerous. Demonstrates the adaptable nature of the system as a whole.

Good selection of games from different eras but I really feel like Runequest/Glorantha should be there with the original D&D, or at least mentioned somewhere.

It’s a good list, but it seems a bit much for a single semster course. I’m going to suggest dividing it in half, with the fall semster focusing on material upto and including D&D 3rd, and winter semster covering material created afterwards. I think this is a nice dividing line, as 3rd comes out around the same time that the internet goes mainstream, and the interaction between fans and designers massively changed how games are designed. There are major design movements that basically come out forum discussions, which just couldn’t happen in the pre-internet publisher driven industry.

RE: “Whither the Universal System?” I think you could make a case that universal systems have evolved into adaptable systems such as 2d20, Storypath, PbtA, Cypher, FATE, etc. which take a few core mechanics and tweak them to fit a particular genre.

@Sapper: Fiasco is a story-telling game, which he already included in the list of notable absences.

Yeah, I’d also agree that RuneQuest / BRP is probably the first universal system.

Runequest is also interesting because of its position as the popular early counterpoint to D&D (with several very opposite design choices):

– the default world and the tight integration of the system with the world

– it is much less ‘gamey’ in places, with no levels or XP, much more tightly associated damage and even associated character advancement mechanics

– it models humans rather than superheroes. Adventurers do not have this obvious exception case from the rules that cover ordinary people because they get to level up and ordinary people don’t, which has always been a bit janky in D&D.

– They also get better at things at far more appropriate rates – going adventuring for a couple of months can’t possibly take you a long way down the road from peasant to god. (Crazy heroquest excepted, I guess 🙂 ).

Although I’d agree the course is probably too full to squeeze it in.

As someone who’s been RPGing since D&D White-Box Edition (approaching 65 now & Still playing on a fairly regular basis) I found this quite a fascinating (and nostalgic) piece & I’d agree with pretty much all your decisions.

I did note the omission of “Empire Of The Petal Throne” but can appreciate that the first edition, game setting aside was design-wise almost identical to original D&D…

I was more surprised by the omission of Runequest because, as others have pointed out it deliberately took some very different design options to D&D, particularly it’s adoption of a resolution system based around distinct, individual skills (which admittedly “Traveller” also picked up on, though using a different resolution mechanic) which may have laid the basis for the “simulation=good” design ethic of the universal RPG’s which you discuss, also as others have noted how (certainly in it’s initial incarnation) the game system was more closely tied to the game’s original setting of Glorantha. Also, as others have noted, how the system could lay a claim as the first universal RPG system as it branched into “Call Of Cthulhu”, “Stormbringer”, “ElfQuest” et. al. via “Basic Roleplaying System”

Agree re BRP: “GURPS / CHAMPIONS” -> “BRP-GURPS-CHAMPIONS.” BRP (1980) is the original, universal, character-customizing, d100 system, the progenitor of CoC (1981) and Elden Ring. GURPS was ’86. BRP came of RuneQuest, which was as popular as D&D in the UK. A fun gander: https://programs.best50yearsingaming.com/.

“VERY suprised at the snub of F.A.T.A.L.”

Indeed. Are you *truly* a RPG player if you’ve never rolled for anal circumference?

Personally, I’d add Tunnels & Trolls. As the second RPG, it introduced a large number of innovations:

* unlike OD&D, where attribute scores largely go unused, in T&T they are very important

* the magic system introduces concepts that would make their way into many other RPGs – spending fatigue to power your magic, intelligence requirements to learn spells

* a “vs” combat system, where each side rolls and the rolls are compared

* the idea of an attribute-based “saving roll” (which Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes would expand into a general mechanic)

Empire of the Petal Throne because it was the first RPG to come with a setting and a skill roll mechanic (buried way into the book) and it was the first historical/culture RPG.

The major omission would be Pendragon. Designed to tell one type of story and tell it well and explore and enforce character attitudes during play so that they have an effect on the narrative and the play.

Re: generic systems, I’d argue that Savage Worlds is a notably popular generic system, and it’s less than 20 years old (only by a couple of years, but still.)

Cypher’s reasonably popular and only a decade old.

Another thing about Paranoia 1st Ed – it was one of the first mainstream games that systemically gave characters conflicting agendas within the game. While they did it for the funsies, the fact that your mutant group and secret society would give you instructions along with the mission briefing – and that each characters would be different – brought a designed chaos to the sessions that other games of the time didn’t have.

Re: universal systems dying out

I respectfully submit Fantasy Flight né Edge Studio’s Genesys, which came out of the late Star Wars Edge of the Empire/Age of Rebellion/Force and Destiny games.

A good example not only of how a system can be universally applied to various genres with a little tweaking, and also a great example of alternative dice mechanics to drive either the game or the story.

Great article… lots of memories. My only change would be to start the list with any “Choose your own adventure” book. For me, they were the gateway to D&D.

PS… I hate GURPS. Played Champions but, as well, TMNT during the same time period.

Has Justin ever written at length on the “failure” of the VtM Storyteller system?

Missing 2 big titles…

D6 Star Wars: the gold standard for both licensed RPGs and systematic elegance. Cinematic gameplay that you can practically hear the John Williams soundtrack as you pull off spectacular deeds.

Savage Worlds: a perfect example of how ‘universal’ RPGs don’t have to be complex mathematical exercises, or require loads of dice. Flexible for anything any GM can homebrew. Heck, it even made RIFTS playable.

I don’t think you should teach a TTRPG course without understanding the human elements behind the games. We don’t study literature without considering the authors.

To that end I’d recommend the book Of Dice and Men. I found it engaging and relevant.

I enjoyed your list and was right there with you on the choices. (Paranoia !). I have some love for Shadowrun and it would be an interesting discussion about dystopian games.

Other notable absences:

“Minimalist” games, that strive for less and get mostly out of the way as a design goal. There are many, but I’d choose Into the Odd / Electric Bastionland because it’s extremely successful at its goals, it has a very prolific lineage, and McDowall has many blog posts about its design rationale.

Collaborative/GM-less games.

Solo games.

You put Fate on the list without mentioning it’s parent, Fudge?

I would replace Paranoia with Ghostbusters. Not only was Ghostbusters a much more influential game on a design level, but you also get to fit in Petersen if you’re not going to include Call of Cthulu. And Vampire: The Masquerade wouldn’t exist without Ghostbusters, because it uses a similar dicepool system.

It also destroys the illusion that rules-lite games are a recent innovation, which I realize was the point of Amber, but Ghostbusters is roughly five years older.

I would agree with the BRP assessments – along with how elements of T&T made its way into Moldvay/Cook. Agree with the idea around pendragon – but rather than have people read them I would do a lecture that talks about rules that hew close to a concept like Star Wars d6 and pendragon and numerous others.

It is hard to remember this is a class on design elements and not a survey or history- in the case of the later it’s Peterson and co all the way.

l would have included a least a passing reference to the D6 Dice Pool System of West End Games. For a lot of gamers, myself included, the innovation of not just the system but the company’s attitude towards rules and narrative was a milestone in the hobby.

That system, especially as it appears in Star Wars and Ghostbusters, hits the sweet spot between crunch, fluff, and how the two relate in a way few others do.

Furthermore, its DNA lives on in so many modern games like the Year Zero System and a host die Pool ganes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNS_theory

Because I had to look it up.

Agree with Runequest comment. My first RPG group switched from D&D to RQ because of the setting and the more simulationist rules (especially, for combat). When I later picked up Call of Cthulhu, Stormbringer and Elfquest, I already knew most of the rules.

Little typo in the Amber section: Disceless

“Before we get to GNS, though, Amber Disceless Role-Playing”

—

I would take this course… as long as the homework wasn’t crazy 😮

For Paranoia, are you saying it went into detailed simulation and it didn’t go well, demonstrating the flaws of this approach? Or that it consciously was showing that it was a bad idea? Or something else?

Notable absences = student projects/term papers

Came here to support RuneQuest and found a half dozen others had done so already. RuneQuest was the #2 game for awhile (and might have been #1 in UK? for awhile) for a reason. It also is a big part of how Warhammer was born. Add that to the other positives listed and its far more important than GURPs in early gaming. It also the deal with Avalon Hill and collapse that followed might be fun to discuss.

And it started Universal Game systems, birthed Call of Cthulu (which still ranks high on number of players), and one of the first (if not the first) to including a setting.

i think rolemaster would be an interesting addition, as it does duty as 1. early fan expansions of D&D in a simulationist direction 2. precursor for 3e and 3. an (excellent) universal system.

it gets a lot of guff, but once you accept that you’ll need to photocopy a few lookup tables it’s a very fast and slick game.