A common form of mapping for RPG cities is the block map. For example, here’s the city of Kintargo from the Hell’s Rebels adventure path:

A common mistake when looking at such a map is to interpret each individual outline as being a single building. For example, when I posted a behind-the-scenes peek at how I developed the map for the city of Anyoc years ago, a number of people told me I’d screwed up by leaving too much space between the buildings. Except the map didn’t actually depict any individual buildings: Each outline was a separate block, made up of several different buildings.

When people look at a block map and interpret it as depicting individual buildings, how far off is their vision of the city?

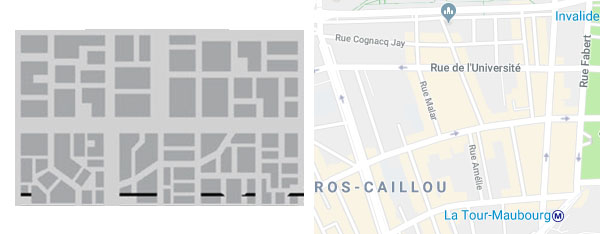

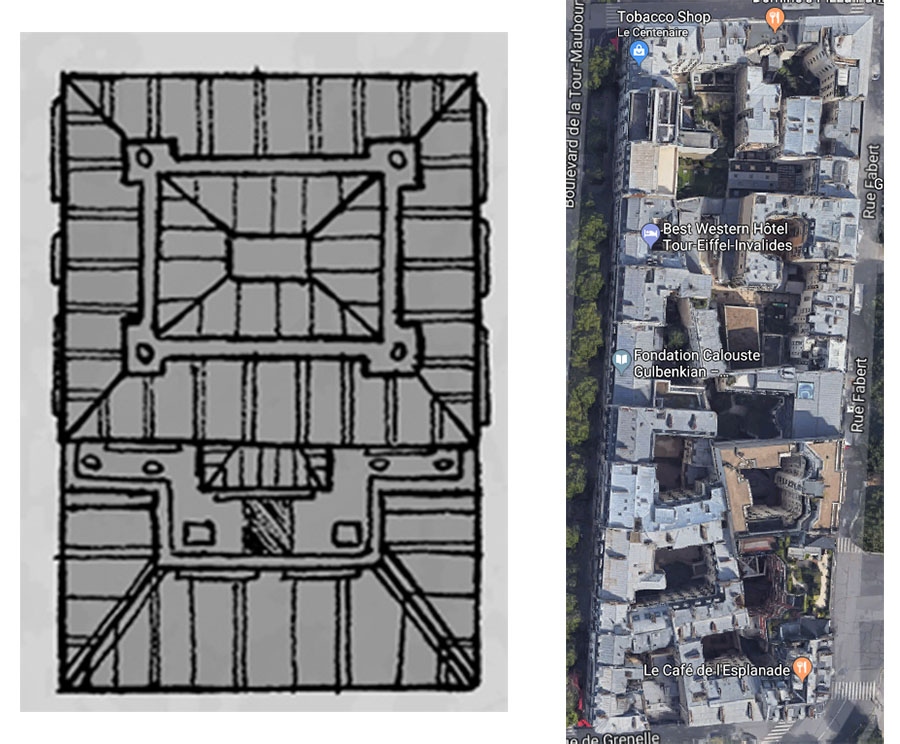

Well, we can actually see this exemplified in a few cases where artists have (in my opinion) misinterpreted block maps. Blades in the Dark, for example, has a block map for the city of Duskwall. Below you can see a sample of that block map (on the left) next to a block map of a section of Paris (on the right).

If it was not self-evident, the interpretation of the Duskwall map as a block map is supported by this description of the city from the rulebook:

The city is densely packed inside the ring of immense lightning towers that protect it from the murderous ghosts of the blighted deathlands beyond. Every square foot is covered in human construction of some kind — piled one atop another with looming towers, sprawling manors, and stacked row houses; dissected by canals and narrow twisting alleys; connected by a spiderweb of roads, bridges, and elevated walkways.

You can see that if you interpret Duskwall’s map as detailing individual buildings, the layout of the city actually becomes far more organized and well-regulated than seems intended by the text. This is, in fact, a common problem when GMs misinterpret block maps: Their vision of the city, and the resulting descriptions are heavily simplified.

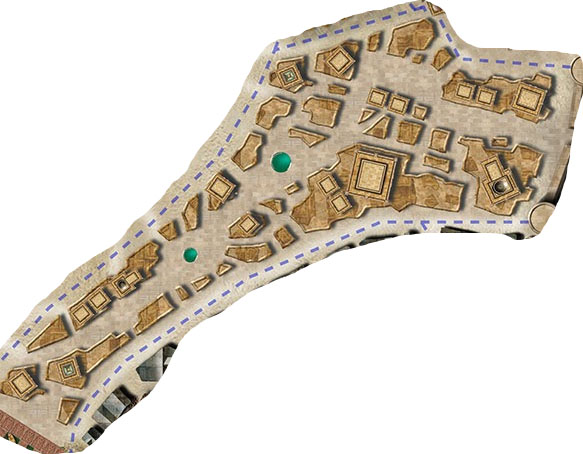

For example, when Ryan Dunleavy decided to develop a large version of the Duskwall map, he interpreted each block on the map as being an individual building (or, occasionally, two). Compare the resulting illustration of a single block in Duskwall (on the left) to what a single block in Paris (on the right) actually looks like:

(Please don’t interpret this as some sort of massive indictment of the artist here. Ryan Dunleavy’s cartography is gorgeous, and I recommend backing his Patreon for more of it.)

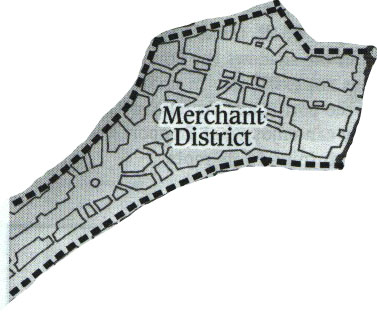

You can see another example of this with Green Ronin’s Freeport. When first revealed to the world in 2000’s Death in Freeport module, the city was depicted using a rough block map:

In 2002, for the original City of Freeport, this was redone with most of the blocks being represented as individual buildings:

The map was redone again for The Pirate’s Guide to Freeport, this time reinterpreting the original outlines as a block map:

I pull out this example primarily to point out that sometimes a block map outline IS, in fact, a single building. Because some buildings are really big. Or, in other cases, they might represent walled estates, as shown here with the estates along the western edge of the map.

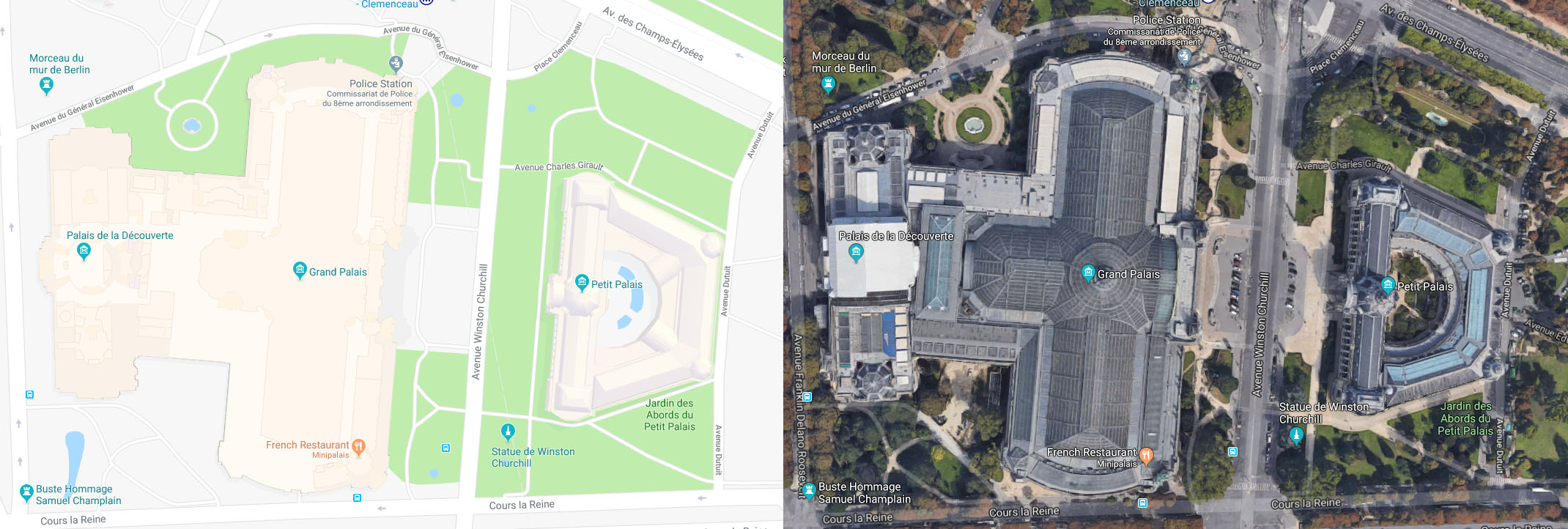

And here’s a real world example of this from Paris with both the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais:

(click for larger size)

The north-south cross section of the Grand Palais is fairly comparable to the Parisian block shown above.

CONCLUSION

My point with all this basically boils down to don’t mistake the map for the territory. One of the great advantages of the block map approach to city mapping is that it leaves so much to the imagination, allowing both you and your players to lay in immense amounts of fractal complexity onto a simple geometric shape.

(Which is not to say that block maps are the be-all or end-all of utility at the gaming table. You can take my copy of Ed Bourelle’s Ptolus map when you pry it from my cold, dead hands.)

And when you miss that opportunity — when your mental image of the block map reduces each geometric shape to a single building — you’re robbing the city of its grandeur, its complexity, and its flexibility.

Take a moment to go back and look at the map of Kintargo, for example. Imagine what that city would look like if each block were, in fact, a single building. What you’ll probably end up with is a modest city still possessed of some good degree of size. But what you should actually end up with in your mind’s eye is this: