SESSION 22C: WORKINGS OF THE CHAOS CULTS

May 18th, 2008

The 10th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

The walls, floor, and ceiling of the room were covered in a haphazard array of magical circles, symbols, and strange characters. The sight was almost dizzying. After little more than a glance, Tee called out for Ranthir to join her.

Ranthir quickly identified the symbols as belonging to a variety of rites, although none were immediately known to him. He did note that many of them bore a more than superficial resemblance to the rites performed by the Seyrunian demon-binding cults of the previous century. And others seemed to have something to do with the creation and binding of energy. Some simply seemed to be mad scribblings to which Ranthir could not ascribe any immediate sense. One particular section of the wall had been completely covered in charcoal, and then written upon in chalk:

Tee, meanwhile, had discovered that one of the wood panels on the floor was loose. Prying it up revealed a small cache containing two books and a gold ring bearing the device of a broken square:

Ranthir was immediately distracted by the books. Eagerly taking them from Tee’s hands he began flipping through them.

TRUTH OF THE HIDDEN GOD

What appears, at first, to be a copy of the Book of Athor is nothing of the sort: The pages inside are covered with scrawled diagrams and heretical desecrations of the Nine Gods.

A closer reading reveals this to be a cult manual for the “Brotherhood of the Blooded Knife”. The cult venerates chaos in all its forms, focusing their blasphemous rituals around the practice of human sacrifice. These sacrifices are given to a Galchutt named Abhoth, who they venerate as the “Source of All Filth” and the “Lord of the Zaug”.

Disturbingly, much of the book is given over to material designed to mock the holy rituals of the Church. It appears that the cult establishes itself secretly in society by posing as other religious orders. Actual followers of the deity may choose to join them, usually to their dismay – either they come to join the cult itself or they die beneath the cult’s “blooded knife”.

In other cases, a few cultists will infiltrate another religion and use force, blackmail, magic, or simple persuasion to sway its members into secretly worshipping chaos. This process can take years, but eventually the cult eats the other religion from the inside out, consuming it until the temple is entirely a front for the altars of the Brotherhood hidden in their subterranean complexes.

The last few pages of the book appear to be a prophetic rambling of sorts, beginning with the words: “In the days before the Night of Dissolution shall come, our pretenses shall drop like rotted flies. In those days the Church shall be broken, and we shall call our true god by an open name.” The remainder of this section is a description of the faux religious practices for a fanciful “Rat God”, with the apparent intention being that a church could be openly established for this “god”. Eventually, the prophecies, say even this “last pretense” will be abolished and “Abhoth shall be worshipped by all who are not blooded by the knife”.

TOUCH OF THE EBON HAND

The pages of this volume are filled with disturbing and highly detailed diagrams of the most horrible physical deformities and mutations. A closer reading quickly reveals that these deformities – referred to as “the touch of the ebon hand” – are venerated by the writers as the living personification of chaos incarnate. Particularly prized are those functional mutations – an extra eye or oversized arms, for example.

The rest of the book describes horrid rites which make it clear that the Brotherhood of the Ebon Hand not only idolizes deformity and mutation, but seek to inflict it and spread it as well: Ritual scarring. Magical alteration. Alchemical experimentation. Chaositech-induced mutation.

Members of the cult have no distinctive garb, but they usually bear the symbol of a black hand in some form: A tattoo. A charm. A small embroidery on their clothes. Or so forth. Of course, most of them are also marked by their mutations.

THE COBBLED MAN

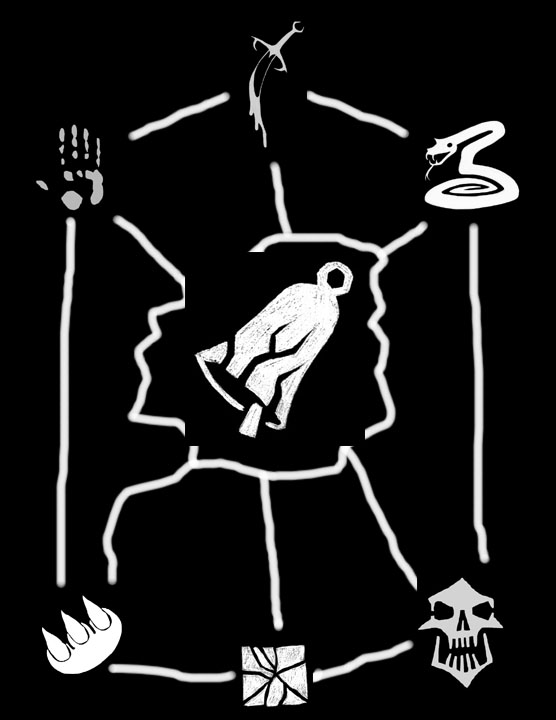

As Tee continued searching, Elestra also came into the room. Looking over Ranthir’s shoulder she pointed at the charcoal wall: “We’ve seen three of these symbols now. The hand, the knife, and the broken square.”

“I wonder what the others could mean.”

“Something to do with the cults, I guess.”

They continued chatting quietly as Tee probed at the walls and the floor.

Dominic, in the tower outside, stood looking in at them. And then pain rushed through his body as a heavy blow landed across the back of his skull.

Stumbling forward he felt a horrible wave of nausea rip through his body. Turning he saw a horrific, monstrous man: A second head had been awkwardly attached to its shoulder, and the muscles of its arms and legs were grotesquely over-developed. The hair on both of its heads was greasy, lanky, and sparse. The eyes on one of the heads was shut, but the eyes of the other were filled with rage. In its right hand it clenched a silvery rod.

“WHY ARE YOU IN WUNTAD’S ROOM?”

Its voice was a dull boom. Its words sullen.

Tor, reacting almost instantly, rushed up the stairs from below. Emerging into the cramped base of the tower, he was clipped nastily along the side of his head. Like Dominic, he felt a nauseous wave pass over him. Shaking it off, he swung his sword – opening a vicious gash in the creature’s arm.

Ranthir rushed out, as well. “Can’t we just work this out?” But his voice was drowned out in the sudden chaos of the melee.

But then Tee shoved her way past him and her voice carried a greater authority: “Stop it! Wuntad sent us! Stop it now!”

The creature froze, its massive hand hovering to deliver a devastating blow on Tor. “Wuntad sent you?”

“Yes,” Tee lied, putting as much earnestness into her voice as she could. “He sent us.”

“He’s been gone so long. I’ve been alone for so long…” The dimwitted voice was filled with painful sorrow.

Tee softened. “Are you the Cobbledman?”

“… someone called me that. Once. They left too. A long time ago.” The Cobbledman clutched absently at the rags on his chest. “They left me all alone… Do you have any food?”

Ranthir fumbled at one of his pouches and then held out an iron ration. “Why didn’t you leave?”

“Can’t leave.”

“Why can’t you leave?”

“Wuntad put something in my brain. Make me loyal. Make it hurt to leave. Can’t leave until Wuntad say I can leave.”

Ranthir had a sickly certainty that this was a betrayal of the flesh. He could see telltale lumps beneath the Cobbledman’s skin – tubes and… other things.

“What happened to Wuntad?” Tee asked.

“Don’t know. The angry men in the metal suits came. There was lots of angry noise. I hid in my tower. And then everyone left… You’ll leave me, too, won’t you?”

No one had an answer for that.

“Cobbledman,” Tee said carefully. “Do you have a piece of metal that looks like a spiral?”

A look of something very like panic entered the Cobbledman’s eyes. “Yes.”

“Could we have it?”

“No! No! My friend gave it to me! I have to keep it safe! She said so!” His hand groped against the rags on his chest, clutching something beneath them.

“I understand,” Tee said gently. “But if we promised to bring it back, do you think we could borrow it? You could even come with us.”

“Maybe…” The Cobbledman seemed to be losing focus. “Do you have any more food?”

Ranthir gave him some more and the Cobbledman chewed it absentmindedly. “I’m going to go to sleep now. So very hungry…”

He began shambling back across the bridge and disappeared into this tower. They watched him go, sadness and pity filling their hearts.

“Well,” Tee said. “At least we know where one part of the spiral key is. Now we just need to find out where Radanna hid hers.”