Go to Part 1

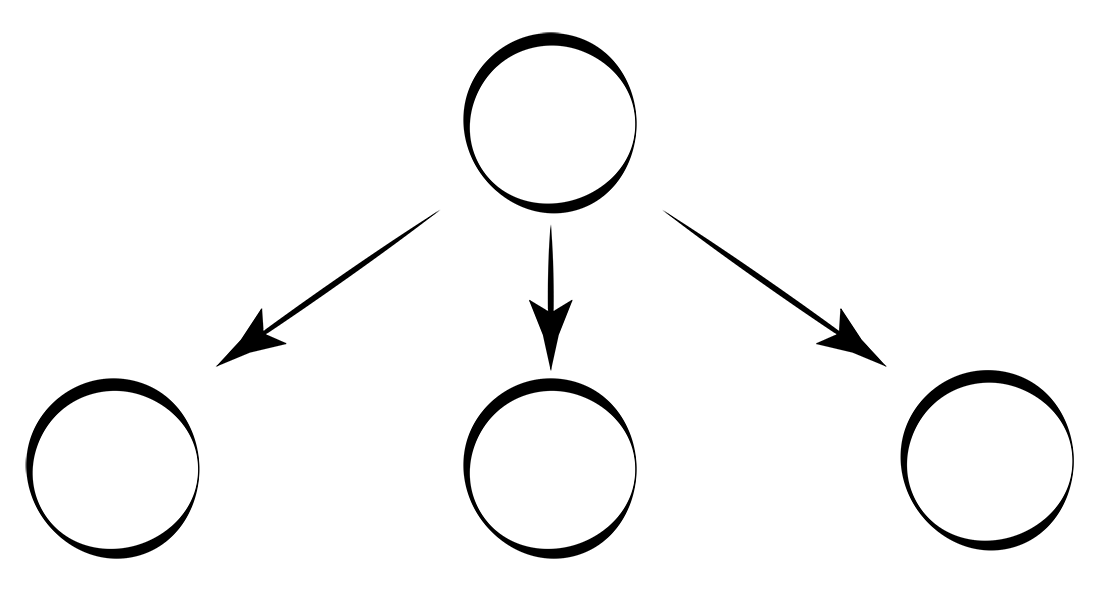

When talking about node-based design, I’ve generally used examples of single scenarios (and usually quite simple scenarios). This has the advantage of keeping the examples relatively uncluttered, but can also be inadvertently deceptive by masking the true power of node-based design.

For example, nodes can be locations, characters, organizations, and so forth. But conceptually they can also be entire scenarios.

This is usually how I design campaigns: I start by brainstorming the major scenarios that are part of the campaign. I think of each scenario as a node and I connect these nodes with clues, following the standard Three Clue Rule, Inverted Three Clue Rule, and all of that. For the sake of argument, let’s call these campaign nodes.

Once I’ve sketched out that broad plan, I can look at each individual scenario and work it up in detail. Many of these scenarios will also be node-based (featuring scenario nodes), although it’s easy enough to mix in other scenario structures (like dungeons or raids or parties or whatever) as appropriate.

The 5-Node Mystery essay has an example of this process. The 5-Node Mystery itself is a basic node template for creating a simple mystery scenario with five nodes – an initial node, three locations/people, and a finale arranged into a simple pattern. You can whip up five of these simple mystery scenarios and then arrange them in the exact same pattern as campaign nodes to form a full campaign.

You can also invert this process, starting with a single scenario, linking it to other scenarios, then linking those scenarios to still more scenarios, organically building up a node-based campaign. (This can obviously work well as a way of building an active campaign week-to-week as you play.)

Note: Not every campaign node necessarily needs to be a full scenario. You might have a bunch of campaign nodes that are full scenarios (unfolding into much greater specificity) connected to another node that’s simply “Admiral Dawson” (a single NPC).

THE CAMPAIGN BINDER

My campaign notes generally live in a binder. The first section of this binder contains all the campaign-wide details — lists of campaign nodes, revelation lists, etc. Then each additional section is an individual scenario or similar chunk of information.

To keep the individual scenarios / campaign nodes organized, I’ll frequently number them. They’re usually also sorted into conceptual bundles. You can see an example of this in Part 7 of the Dragon Heist Remix:

0.0 Campaign Overview

1.0 Finding Floon

2.0 Trollskull

3.0 Nimblewright Investigation

3.1 Gralhund Villa

4.1 Faction Response Teams

4.2 Faction Outposts

5.0 Heist Overview

5.1 Bregan D’Aerthe – Sea Maidens Faire

5.2 Cassalanter Estate

5.3 Xanathar’s Lair

5.4 Zhentarim – Kolat Towers

6.0 Brandath Crypts

6.1 The Vault

To briefly summarize:

- The 0.0 document is the campaign-wide material.

- Node-based design mostly kicks in with Part 3.0, which is a node-based mystery in which the solution is going to Part 3.1 (which is a raid scenario).

- The 3.1 raid contains a bunch of leads pointing to other scenarios. I’ve broadly organized these into Part 4 (faction-related stuff built as a sort of node campaign inside the node campaign), Part 5 (the major heists, which the PCs are pointed to by leads in Part 4), and Part 6 (the final scenario, which is built as a dungeon crawl and further broken into two parts for convenience).

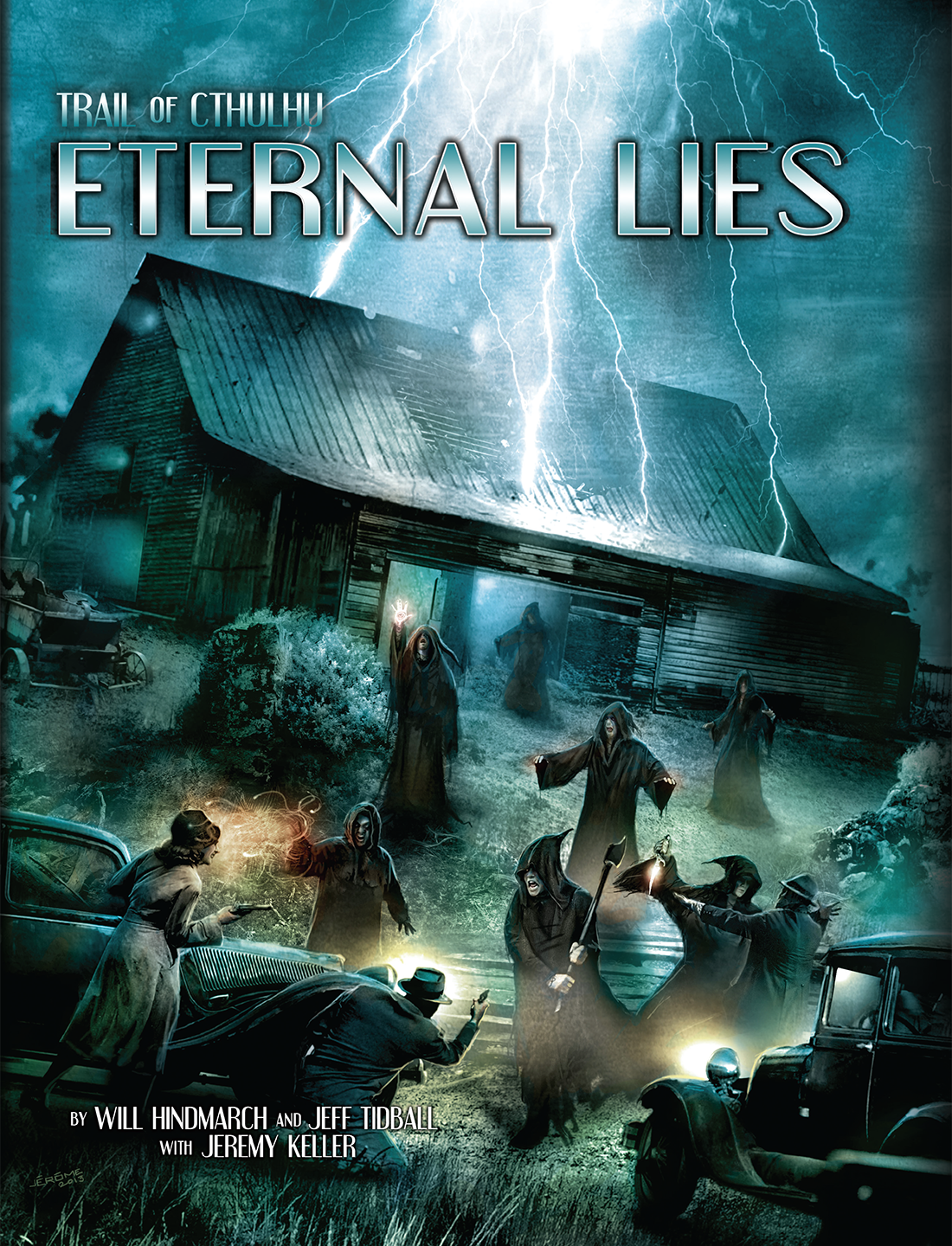

Sometimes this conceptual structure is literally just the nodes themselves in a simple list. Masks of Nyarlathotep and Eternal Lies use a globetrotting structure to similar effect: Each major city visited by the players is treated as a separate scenario (i.e., a campaign node) with links between them.

Act II of my Ptolus: In the Shadow of the Spire campaign has forty-two different scenarios. In addition to conceptually breaking the campaign into acts, I have further divided this act of the campaign into three sections, using prefixes to distinguish them. (So this campaign features adventures with organizing codes like NOD4, CC3, and BW09. Which may sound confusing, but is perfectly clear in context.)

My big point here is that there’s not necessarily a “one true way” here. It’s what works for you and it’s what works for a specific campaign.

USING NODES TO MANAGE PREP

The conceptual separation of a campaign into separate nodes is also a great way to manage prep and, in accord with the principles of smart prep, minimize wasted prep.

Basically, you can set up the essential elements of a campaign node (in terms of how it connects and interacts with other campaign nodes) without fully prepping the scenario that lies “behind” that campaign node. Therefore, you don’t actually need to prep that scenario until the PCs move to engage it.

For example, when I originally laid out Act I of Ptolus: In the Shadow of the Spire, it featured thirteen scenarios. Because of the choices my players made, however, I ended up only needing to prep seven of those scenarios.

The high-level view of the campaign gives enough detail to have a complicated web of interrelated content, while also conceptually firewalling the campaign in a way that prevents you from pouring a bunch of extra detail into areas where it turns out you don’t need it.

Note: As you design and expand individual campaign nodes, you’ll often find new opportunities to link the node to other nodes arising naturally out of the material. Do so. As a corollary of the Three Clue Rule suggests: More clues are always better. (Make sure to list these new connections in your campaign-wide documentation, too.)

ADDING NODES

The modular nature of node-based design, however, also makes it easy to integrate new nodes into your campaign structure.

In fact, it’s not unusual in the slightest for the actions of the PCs to generate new nodes by either creating leads out of whole cloth (by pursuing methods of investigation or a strategy of action that I hadn’t anticipated) or following leads that I didn’t realize were leads when I made them. I discussed one example of this in Ptolus: In the Shadow of the Spire here, as the unexpected actions of the PCs added two completely new nodes to Act I (even while they were, as noted above, ignoring six other nodes I had planned).

Something similar happened in the Eternal Lies Remix, with the players choosing to go to the Severn Valley by following information that wasn’t explicitly designed as a lead, but which they nevertheless interpreted as such.

As the GM, you may also find yourself proactively creating new nodes that arise logically out of the evolving circumstances of the game. The Shipwrights’ Ball in my Dragon Heist campaign is an example of that.

As you’re adding these nodes to your campaign, don’t forget to link them to other campaign nodes just like you would with any other node. You don’t need to worry about making sure to include three clues pointing to the new node (you’re designing the node because the PCs are heading there; you don’t need redundancy to make sure they do the thing they’re already doing), but seize the opportunity to add new leads pointing to other nodes. (For example, when adding the Laboratory of the Beast to In the Shadow of the Spire, I added several new links to Act II of the campaign.)

These connections will often arise naturalistically in any case. If the PCs become interested in a mobster’s yacht or lawyer or ex-wife because of their connection to the mobster, it just makes sense that those things could be potentially connected to the mobster’s other affairs (i.e., the other nodes connected to the mobster in the campaign).

Note: There are plenty of exceptions to prove this “rule.” If the PCs go haring off on a wild goose chase, it’s perfectly fine for them to discover that it’s a dead-end in terms of their wider investigation. (Of course, this doesn’t mean that they won’t find something interesting there. The Manse of the Red Dragon sounds pretty exciting even if it doesn’t have any connection to the conspiracy of Elf Lords.)

In some cases, you may find that the PCs have blasted open a whole new multi-node section of the campaign. That’s great! Just remember not to prep more of those nodes than you immediately need to.

META-SCENARIOS

I spoke earlier about the two prongs of mystery design: That there are leads which point to other nodes where you can continue investigating things and clues that point to other types of revelations (like the solution to a mystery). Furthermore, the latter can be spread out over the course of an entire scenario, with the PCs slowly accumulating the clues they need to piece things together.

This same principle can hold at the campaign level: You can take a big mystery, break it down into separate revelations, and then spread the clues for those revelations out over the entire campaign (perhaps dropping only one or two in a given scenario).

This is a meta-mystery, and it’s an example of what I call a meta-scenario.

Although the design principles here, like much of what we’ve been talking about, are the same as they would be for an individual scenario, in some cases a difference in scale is a difference of kind. Largely, this is a matter of organization: I usually find that meta-scenarios require their own section of the binder. I find them easiest to both design and manage if I think of them as a distinct entity that’s kind of being “draped” over the top of the campaign’s primary structure.

Meta-mysteries are not the only sort of campaign-spanning meta-scenario. Other examples might include:

- Collecting the specialized components for performing a ritual.

- Making allies for the Prophecy War.

- Being hunted by an intergalactic cabal of assassins.

- A countdown to the apocalypse as the Stars Come Right.

Go to Part 3: The Fractal Node

hexcrawls). Others are just misnomers (like sandboxes being the opposite of a railroad).

hexcrawls). Others are just misnomers (like sandboxes being the opposite of a railroad).