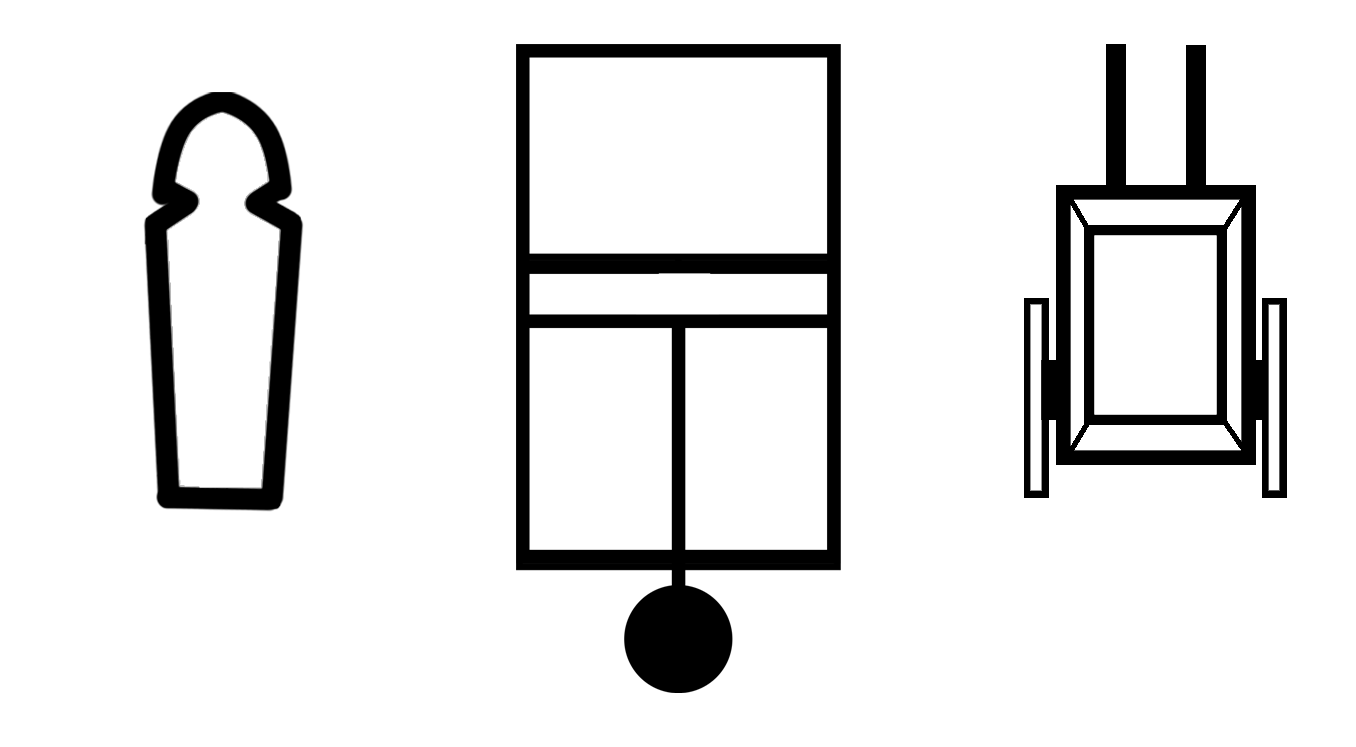

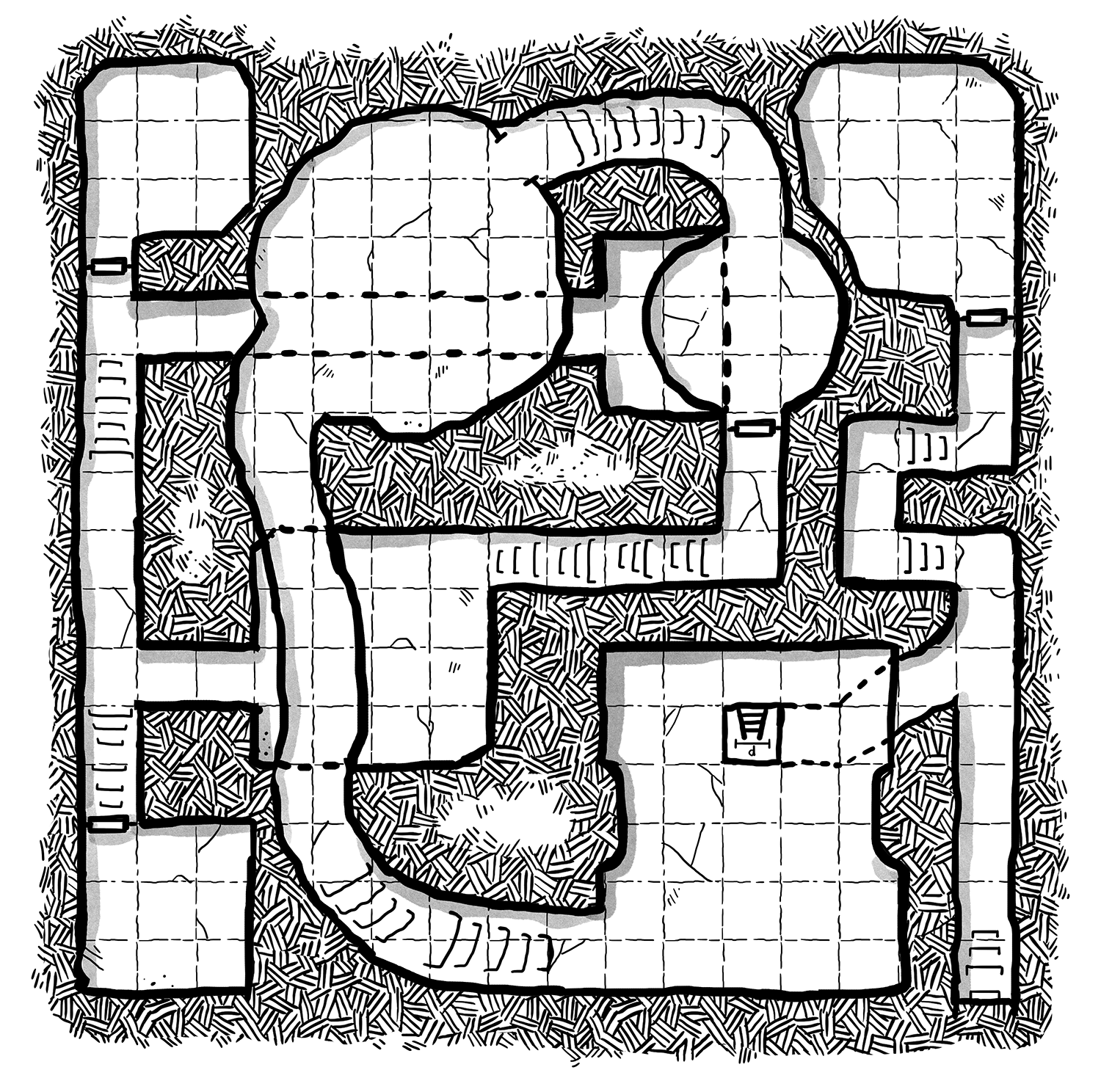

A player scratching out a map of the dungeon on graph paper as their DM describes the winding corridors and strange labyrinths their character is exploring is a tradition which predates Dungeons & Dragons itself. It’s become almost habitual; passed down from one generation of gamer to the next: We’re entering the dungeon, so who’s going to be the mapper?

But like a lot of unexamined traditions, there comes a point where you stop and say, “Wait a minute. Why am I doing this?!”

Theater of the mind was supplemented by Chessex battlemaps and Dwarven Forge terrain, and now we live in an era of shiny virtual tabletops with infinite scrolling maps. Player mapping used to be fairly ubiquitous in video games, too, but it’s been almost entirely eliminated there: replaced with mini-maps, quest markers, and fast travel. Why not get rid of it in tabletop gaming, too?

There are definitely be costs to player-mapping. In some campaigns, in fact, the cost can be quite substantial: The GM repeating room dimensions. The group waiting for the mapper to finish. Confused Q&A sessions between the GM and the mapper as they try to clarify exactly what an odd-shaped room looks like or the precise angle of a hallway. All of this drags down the pace of play and distracts the group from all the other cool stuff — combat, exploration, roleplaying — that’s happening in the dungeon.

So what are we doing here, exactly?

WHY PLAYER MAPPING?

The first thing to understand is that player mapping is only worthwhile if navigational knowledge has value.

In many modern D&D scenarios, it doesn’t: The dungeon isn’t dynamic, it’s overly linear, and/or the goal of the adventure is “kill all the bad guys.” Plus, the adventure is often balanced so that the PCs can wrap up the whole dungeon in a single long rest. So the PCs’ navigational choices don’t actually matter: Even if there are multiple meaningful paths through the dungeon, the choice of path is essentially irrelevant because the PCs ultimately need to kick down every door and clear every room.

Since their navigational choices don’t actually matter, why would the players waste time on making a map?

Maybe there’s some marginal value in “detecting a secret door leading to a bunch of a treasure we otherwise would have missed” (which is why this is so often discussed these days as the reason for player mapping), but it’s an extremely marginal value. Hard to justify all the rigamarole for that one time in twenty that you manage to suss out a secret room you otherwise would have missed.

(And, frankly, a lot of DMs are just going to fudge the Search check to find the secret door anyway. We wouldn’t want the players to miss any of our carefully crafted content, right?)

So when players say that mapping is pointless, that’s not really surprising. It’s quite possible they’ve literally never played a scenario where mapping provided a benefit.

Somewhere towards the other extreme, however, is the Arnesonian megadungeon: The PCs are going to be going down into the dungeon repeatedly and the layout of the dungeon is heavily xandered, so the navigational information from previous expeditions lets you plan your next expedition. The dungeon is also extremely dynamic, with monsters being restocked and aggressive, even punitive random encounter pacing. In that environment, navigational efficiency is of paramount importance: A good map is literally the difference between success and a failure; a big payday and abject failure; life and death.

(This is not to say that you need a megadungeon for mapping to be relevant. It’s just one example of a dungeon scenario in which the PCs will profit from having a good map.)

Furthermore, when mapping is motivated and rewarded, it turns out there are a few other benefits to player mapping.

First, it ensures a clarity of communication. While it’s possible for mapping to bog down play because the player is seeking an unnecessary amount of persnickety detail (more on that later), it’s much more likely in my experience for the map to become problematic because the player fundamentally doesn’t understand the GM’s description of the game world.

The key thing to understand here is that this needs to be fixed whether the player is mapping or not: If they can’t even figure out where the exits from a room are, for example, then there’s a fundamental mismatch between the GM’s understanding of the game world and the players’ understanding of the game world, and that’s going to cause problems no matter what. When this is happening, the player’s map actually provides valuable verification that the GM’s descriptions are being clearly understood and can help quickly clear up misunderstanding when they do arise.

Second, map-making is a form of note-taking, and like all note-taking it aids memory and understanding. It locks in the events of a session and provides a reference that the whole group can look back on in future sessions to remind themselves of what happened.

Finally, drawing a map can be a very immersive way of interacting with the game world. It’s like how a good horror movie will force the audience to engage in an act of closure by imagining the horrific things which the movie only suggests to them. Because the audience is creatively filling in the gaps for themselves, the result can be more vivid, personal, and emotionally engaging than if you just showed them the monster.

Getting the player to engage in a similar act of closure at the game table — where they, themselves, are ultimately completing the picture of the game world in their own mind — will similarly immerse them into the setting. Player mapping achieves this because it implicitly involves them thinking about what lies beyond the edge of their current map as they try to figure out where they should go next and how the different pieces of the dungeon might link together.

The excitement that generates is one part puzzle-solving, one part reward, and one part being drawn into the fictional reality of the game world. The example of realizing that there must be a secret chamber right here is just one very specific example of what this looks like.

PLAYER BEST PRACTICES

First: Do you need a map?

If you’re a dungeon delver, only make a map if you feel like you’re getting value from it. There are plenty of smaller dungeons and dungeon-like environments where you won’t need a map. (On the other hand, if you’re having fun making the map, then have fun! That’s reason enough.)

Second: Focus on functionality over trying to capture the precise measurements and angles of the dungeon.

In fact, in many cases, you don’t need measurements at all. You can get most or all of the benefits of mapping from a simple network map: Just draw a circle for each room and then draw lines showing how it connects to other rooms.

This doesn’t mean you need to give up on the graph paper entirely, of course. It just means recognizing that most of the time the difference between a hallway that’s twenty-five feet long and a hallway that’s thirty feet long just isn’t important.

Of course, there may be times when you actually need that type of precision. (For example, you might suspect that there’s a secret room hidden somewhere in the haunted house and you want to figure out where it might be.) When that happens, make a point of seeking that precision in character: What is your character actually doing to get the precise measurement that you want?

Third: Map in pencil.

You’re going to make mistakes. As you explore and revisit sections of the dungeon, your knowledge of how everything fits together will grow over time. You’ll want to be able to easily adjust your maps to make all the pieces fit together.

Fourth: Let the GM see your map.

If the GM can easily see your map — e.g., it’s sitting on the table in front of you — it will let them quickly notice errors and give you the necessary corrections.

Don’t expect the GM to fix all of your mistakes, of course. Just the ones that you wouldn’t have made if you were actually standing in the dungeon instead of just listening to a description of it.

Fifth: Make sure to actually USE the map.

This might seem obvious, but your goal is not to produce an immaculate cartographical masterpiece. Take notes directly on the map, and make sure you’re sharing the map with the rest of the group as a reference and resource for decision-making: Where have we been? Where should we be going? What do we know? What do we want to find out?

Sixth: The map is an artifact that actually exists in the game world.

You’re mapping in the real world just like your character is mapping in the game world. Make sure your character has the supplies they need to actually make the map. Think about where and how the map is being stored.

These are small details, but you’ll find they make a big difference in letting the map literally draw you into your character.

Seventh: Try not to let your mapping disrupt or distract from the rest of the game.

Mapping is important, but you should be able to do most or all of it in the background while play continues to flow normally. If you find that you’re constantly having to interrupt the action to get the information you need to make the map, then something has probably gone wrong.

Most likely, you’re seeking a level of precision greater than you need. Try to figure out how to make your map from the details your DM is normally giving you. If you need more detail than that, as noted above, try to seek it out in character (so that it becomes part of what’s happening in the game world rather than a distraction from it).

Eighth: To wrap things up here are three practical tips.

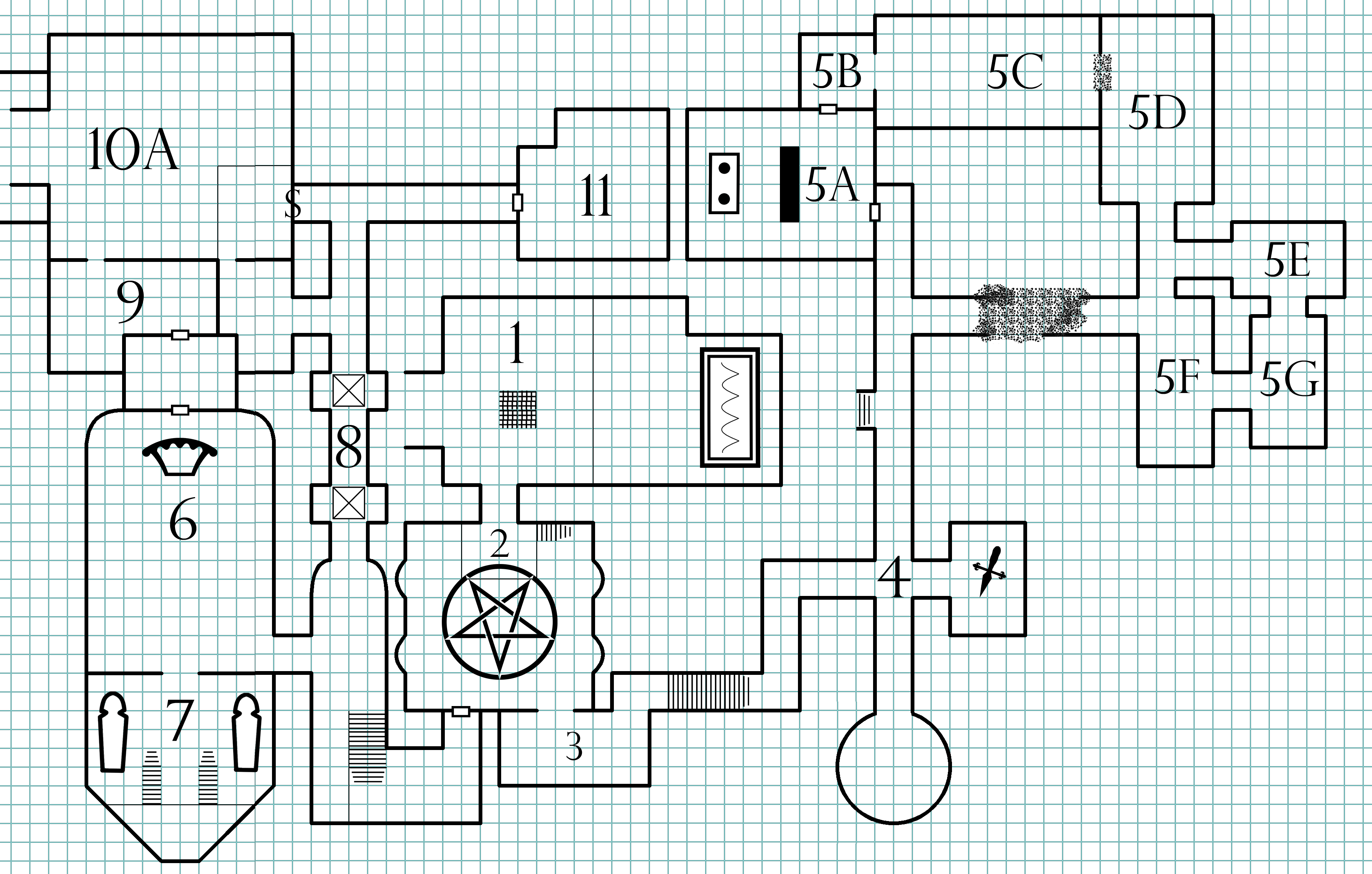

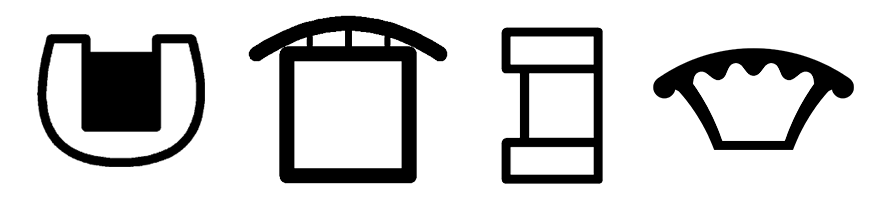

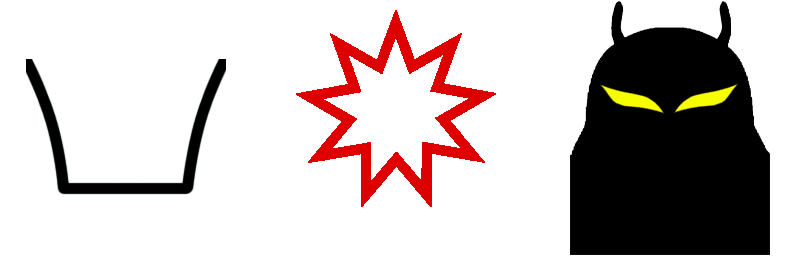

- Learn and use some simple map key symbols. (These are easy to find online, and there’s also a set in So You Want To Be a Game Master.)

- You’re not making a battlemap. Mapping at a 10-foot scale (as opposed to a 5-foot scale) will let you get a lot more of a dungeon level on a single page, which will make understanding, using, and updating your map a lot easier.

- Be aware of elevation changes. Not every elevation change is a level change, but passages passing above or below other passages are an easy source of confusion that can either ruin or over-complicate your map.

Next: Dungeon Master Best Practices