IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 37E: ON THE IRON MAGE’S BUSINESS

May 9th, 2009

The 21st Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

TO THE DOCKS

And then the vision shredded, passing away like the drifting trails of the incense smoke in her room…

Maybe I don’t want to remember what happened… Or was that something that’s still to come?

She cleaned up the remnants of the ritual and stored the rest of the incense back in her bag of holding before heading back downstairs to meet up with the others in the common room. They headed down to the Docks together.

Once there they still had to wait for the better part of two hours, but eventually – under the mid-afternoon sun – they saw the Freeport’s Sword pulling into one of the deep-water piers.

Heading down the long length of the narrow pier, Tee hailed the captain of the vessel, who introduced himself as Captain Bartholomew. He was a dashing fellow, with a broad and merry grin.

“Aye, I have such a crate. And am glad to be rid of it.”

“Why?” Tee asked, casting a worried glance to the others.

“It came strangely from the hand of the Iron Mage. My crew thinks it cursed and have stayed well clear of its hold.”

“He is strange,” Ranthir said.

“You think we can trust him?” Elestra asked.

Ranthir shrugged.

In short order, Captain Bartholomew’s crewmen had unloaded the crate onto the dock. It was marked with the Iron Mage’s sigil (a plated visor beneath crossed wands), and it also proved quite large (nearly six feet square) and impossibly heavy.

“If I’d known it was going to be this large, I could have prepared a spell to move it,” Ranthir said.

Tee turned back to Captain Bartholomew. “How are we supposed to move it?”

“I was hired to deliver it to your care,” Captain Bartholomew said. “And that’s been done. So it’s no concern of mine.” And he ordered his men to start work on unloading the rest of his cargo.

Tee scowled, but there wasn’t much they could do about it.

THE YELLOW TEETH

Elestra volunteered to fetch and hire a cart. The others stayed behind to keep a guard on the crate while she walked back down the pier.

As she reached the Wharf Road, Elestra spotted a small huddle of cloaked men lurking down the alleyway opposite the pier’s end. The ambush was obvious, but thinking that it wouldn’t be sprung until they were leaving with their cargo, she turned down the street and hurried along to find a cart for rent.

Unfortunately, she was scarcely out of sight when the ambush was sprung. Casting off their cloaks, the “men” were revealed to be ratlings. They stormed the end of the pier, joined by nearly half a dozen ratbrutes as well.

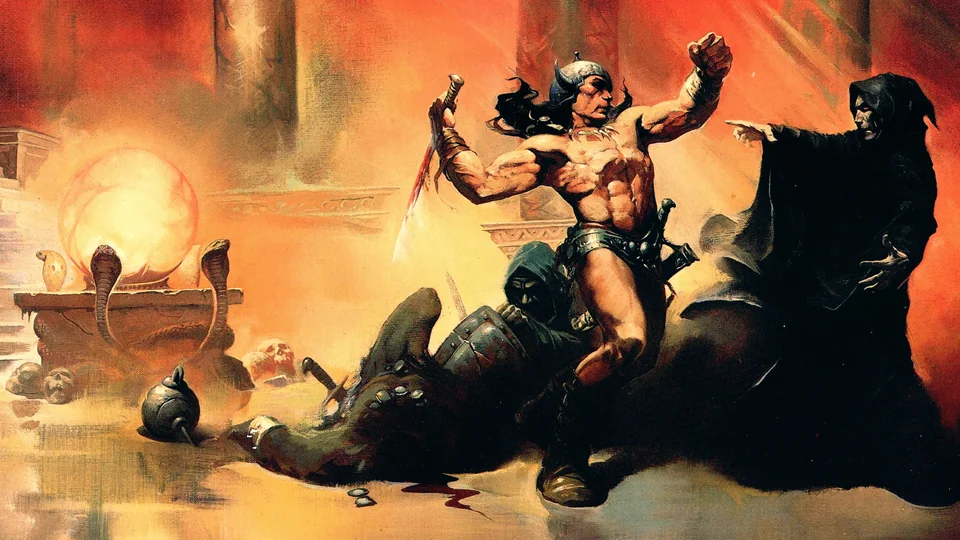

Although caught by surprise (as Elestra had sent them no warning), the others were already on their guard against potential mischief. Long before the ratlings reached them, therefore, they were already moving quickly and efficiently into defensible positions. Ranthir wrapped his magicks around Agnarr, enlarging him to giant-like proportions. The barbarian, his stride increasing with every step, turned and marched down the pier.

The ratlings swarmed to meet him, but were met by Agnarr’s flaming greatsword – working like a scythe through fresh hay. Their assault quickly fell into disarray before him and then, a few moments later, Tor – similarly enlarged by Ranthir’s spells – stepped forward as well. The two of them, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, blocked the pier from side to side.

Tee, meanwhile, had been calling out to Captain Bartholomew and his crew. After a quick bout of negotiation, she successfully hired their aid (at the rather exorbitant rate of 25 gold pieces to the head). With the price settled, Bartholomew led his crew into the fight with whooping war-cries.

The initial assault had now foundered completely. Only two of the ratlings had survived, and these wilier fellows now drew their dragon pistols and fell back to take potshots from the end of the pier. But the battle was far from over, for now the ratbrutes were coming forward.

Agnarr met the first of the brutes as it lumbered near. He cut the creature down easily, the flames of his sword cutting deep into scorched flesh. But one of the other ratbrutes – shouting orders and clearly in command – approached more carefully, with a third ratbrute serving as his second. Their swords scissored out, and Agnarr was caught viciously between them. With a gurgling cry, he stumbled backward and collapsed.

Tor fell back a few steps, but largely managed to hold the line against the renewed assault from the ratbrutes. With Tor occupied, however, the rat-leader gestured crudely and, a moment later, two of the ratbrutes dropped off either edge of the pier and began swimming underwater.

Tee, who had been shooting from the far end of the dock, saw the ratbrutes disappear into the waves. Dispatching one of Bartholomew’s sailors to bear a healing potion to Agnarr, she drew the rest of them into a tight defensive perimeter around the crate.

It wasn’t long before her fears were realized: The two waterlogged ratbrutes clambered up onto the dock behind Tor and rushed the defenders around the crate. Tee and the sailors leapt forward to counter-attack, but in mere moments two of Bartholomew’s crew had already been grievously injured.

At almost this very moment, Elestra finished haggling for the cart and turned back to discover the chaos breaking out down the Wharf Road. With a cry she transformed into an owl and began flying back as fast as her wings would carry her.

Meanwhile, the pirate Tee had sent with healing potions had reached Agnarr’s side. Although he had been cut down only a moment later by a particularly vicious back-handed blow from the leader of the ratbrutes, he had managed to press one of the potions to Agnarr’s lips.

Agnarr was conscious once again, but one of the ratbrutes – who had stepped forward as Tor fell back – was now straddling him. Still badly hurt and separated from his sword, Agnarr knew that he wouldn’t live long if the ratbrutes realized he was a threat. So, for the nonce, he contented himself with surreptitiously sipping healing potions.

But the instant that Tor cut down the ratbrute standing over him, Agnarr leapt back to his feet. His sudden presence distracted the ratbrute leader, who had been moving to flank Tor. Tor seized the advantage and focused all his fury upon him.

The ratbrute seized a healing potion of his own, quaffed it, and fell back. But Tor pursued and cut him another wound for his troubles. The ratbrute might yet have recovered, but Ranthir – from the far end of the pier – struck him in the face with a bolt of magical energy. The blast left him momentarily dazed, and Tor had little trouble finishing him off.

Seeing him fall, Tee cried out to the ratbrutes fighting near the crate, “Your leader is dead! Turn and look!”

But the ratbrutes merely snarled. “The Yellow Teeth never turn! They never retreat!”

They cut down another of the sailors. Tee, enraged, pressed her own attack and killed one of the brutes. But in the action she left her back open, and the second brute – with a hefty swing of his massive blade – cut her down.

One of the sailors cried out. “The pretty lady is dead! She’s dead!” A general panic settled into Bartholomew’s men and a rout had begun.

Agnarr, seeing the danger, ran down the length of the dock. But the remaining ratbrute ignored him and ran for the now utterly unguarded crate. Agnarr’s last, desperate sword swing narrowly missed the creature as it reared back its own massive sword and—

Smashed open the crate!

An inky, stygian darkness suddenly enveloped the end of the pier. The sailors trapped within it began screaming in terror. One, who had been attempting to flee back aboard the Freeport’s Sword, fell from the gangplank into the water below with a gurgling cry. Others, halfway down the dock in their rout, came to a stumbling and bewildered halt.

The ratbrute’s huge rat ass, however, was still hanging out of the darkness. Agnarr chopped him down. At the far end of the pier, Tor was doing the same (although he needed to chase the last of the cowardly ratlings half a block down Wharf Street before cutting him down from behind). “I thought the Yellow Teeth never turn,” he said sardonically over the corpse.

A DARK BEYOND DARKNESS

Elestra alighted on the dock and resumed her human form. She quickly healed Tee (who had been merely injured, not killed).

Ranthir, meanwhile, examined the crate-born darkness. It could be easily identified as a point-source effect, but he needed to know more. He quickly weaved a few spells—

And was blasted into unconsciousness.

When the others managed to rouse him, he told them of a magical aura so powerful that it had literally obliterated his senses when he tried to look upon it. From this, he concluded that any effort on his part to negate it would fail. However, since the effect had previously been occluded by the crate, it might be possible to physically impede it.

To that end, they paid an egregious and ridiculous sum to Captain Bartholomew for a large piece of sail cloth. By wrapping this around the damaged crate, they were able to blot out the darkness. Then they were forced to pay a similarly ridiculous price for a larger crate, which they levered into position and, thus, sealed the broken crate inside.

While those with mightier thews tended to this business under Ranthir’s instruction, Tee and Elestra quickly searched the bodies. In addition to a few small sums of coin and the like, they found upon the body of the leader a letter of some considerable interest:

LETTER FROM SILION TO BATTACK

Battack—

I have need of the Yellow Teeth. A vessel named the Freeport’s Sword will be arriving in port tomorrow. It carries a crate bearing the mark of a plated visor beneath crossed wands. The Tolling Bell has commanded that the contents of this crate be secured.

We have a rare opportunity: None of the other brotherhoods have managed to ascertain the crate’s location. Many still seek it among the islands. If we can obtain it and deliver it to Wuntad’s hand, we shall be honored not only by his hand but in the eyes of the Sleeping Gods.

Do not fail me in this.

Silion

Running the Campaign: Newssheets – Campaign Journal: Session 38A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index