Great Arkham.

Great Arkham.

The year is 1937 and the little towns of Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport have been swallowed up by the cosmopolis of Great Arkham. This sprawling city of cyclopean skyscrapers, dimension-twisting alleys, and Dagon-touched mobsters has no place in history as we know it; it may not even have a place on Earth at all.

Great Arkham is a place where the Stars Are Coming Right. (Or perhaps they already have.) The skein of reality is stretched taut across the Mythos here, and horrors intrude into the daily lives of the citizens. Most have learned how to shut out, suppress, or deny what surrounds them. Some exploit their secret knowledge, embracing damnation and slow obliteration for the temporary blaze of glory. Others, like the PCs, fight back (or seek to escape).

Unfortunately, those are the ones most likely to find that the frontiers of the city are shut to them: Geography warps. Trains break down. Or the enigmatical and terrifying Transport Police (supposedly fighting a never-ending battle against a strange plague of “typhoid” which is never cured) will enforce a quarantine and turn would-be émigrés (escapees?) back… or detain them in facilities where inexplicable and alien lights gleam from barred and shuttered windows.

If that doesn’t immediately sound kind of amazing — a sort of Dark City mixed with glasshouse panopticon mixed with an obscene glut of Mythosian truth that would be almost pulp-ish if it wasn’t so overwhelmingly nihilistic — well… I guess Cthulhu City isn’t for you.

If it does sound amazing, then I’m happy to report that in many, many ways Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan has delivered brilliantly on the concept. He has stitched together a vast array of Mythos elements — something which, in my experience, often goes awry — into a cohesive whole, and in the places where things don’t necessarily quite work out he adroitly turns the weak joint into a point of strength by tying the inconsistency into the bleak, existential horror of the whole thing.

And despite the Kafka-esque oppression inherent to the entire concept, Ryder-Hanrahan nevertheless weaves into the tapestry enough hooks of hope that those not interested in embracing hopelessness, despair, and inevitable destruction can fight back against the darkness.

The result is a rich, intriguing, and potentially very rewarding setting that will allow you to frame unique scenarios that would otherwise be impossible to create. And that, in my opinion, is very high praise indeed.

RESERVATIONS

Unfortunately, I now need to damp that enthusiasm a little bit with a number of reservations.

The first thing I’ll note is that Cthulhu City is sort of an Advanced Trail of Cthulhu in terms of its setting. It assumes that the GM will be possessed of a fairly vast knowledge of the Mythos both broad and deep, and so frequently contents itself with merely making evocative allusions to various elements of the Mythos with the expectation that you will recognize the reference and fill in the details. (Perhaps the most surprising allusion, for me, was to Roger Zelazny’s A Night in Lonesome October, which is a truly delightful book that I make a point of pulling out for a rereading each Halloween season.)

Which is probably fine. Because Cthulhu City really shouldn’t be anyone’s first foray into the Mythos. So whether you build up that stock of Mythos knowledge by voraciously consuming everything Lovecraft (and the other likely suspects like Ramsey Campbell and August Derleth) wrote or by running a campaign or three of Mythos-tinged horrors, Cthulhu City will be waiting for you.

The second thing I’ll note is Ryder-Hanrahan’s technique of describing the setting through “multiple truths”. The book, for example, doesn’t resolve the question of whether Greater Arkham is an intrusion into our reality; a dimensional pocket; a poor recreation of 20th century life by an alien civilization or some future epoch; the true history of our world scooped out of the timeline by intrepid heroes in order to make reality a better place; or something else entirely.

Ryder-Hanrahan drills down and uses this approach at every level of the setting. Every NPC, for example, is described in three different versions — Victim (generally meaning a problem for the PCs to solve); Sinister (someone actively aligned with the Mythos); and Stalwart (a resource or patron for the PCs to benefit from). Every location is given a Masked (the Mythos may be there, but isn’t overt) and Unmasked (the site is a source of immediate danger) version. (Often multiple versions of each are given. There’s at least one NPC who is presented in six different versions.)

Ultimately, this “three versions of the truth, pick one” thing doesn’t work for me. I see what Ryder-Hanrahan is doing. I even praised the similar approach used by Kenneth Hite in the core Trail of Cthulhu rulebook to present the Mythos entities as a catalog of mysterious possibilities instead of an encyclopedia of cemented facts. The problem is that when you apply the same technique to specific setting material, the setting material stops being specific and the tack-on problems become significant.

To start with, I’d rather have two or three times as many cool things, instead of having a handful of things which could be cool in three or four or five different ways. But the bigger problem is how this lack of specificity turns everything into mush. For example, consider Aileen Whitney: “Whitney’s father is a wealthy businessman. A member of the city council visited the family home in Old Arkham one night to discuss a proposal with her father, and Whitney overheard the terrible thing they plotted together.” Which city councilor? It can’t say, because the book doesn’t know which councilors will be cultists. What terrible thing? It never explains, because any explanation would force some other quantum uncertainty in the book to resolve itself.

As a result, the book is filled to the brim with these half-formed ideas. It makes for a very mysterious and enigmatic reading experience as you pour through the tome from one cover to the other. But the problem, for me at least, is that these half-formed ideas just… aren’t very useful.

If you said to someone, “Hey, I need an idea for a scenario this week?” and they responded by saying, “You could have an NPC tell the PCs that they heard somebody plotting something horrible!” would you consider that particularly useful? I wouldn’t. Useful would be the actual thing they heard; the meaningful meat that would serve as the scenario concept.

What we’re left with instead are hooks to vapor.

POOR ORGANIZATION

The other major problem with Cthulhu City is its poor organization.

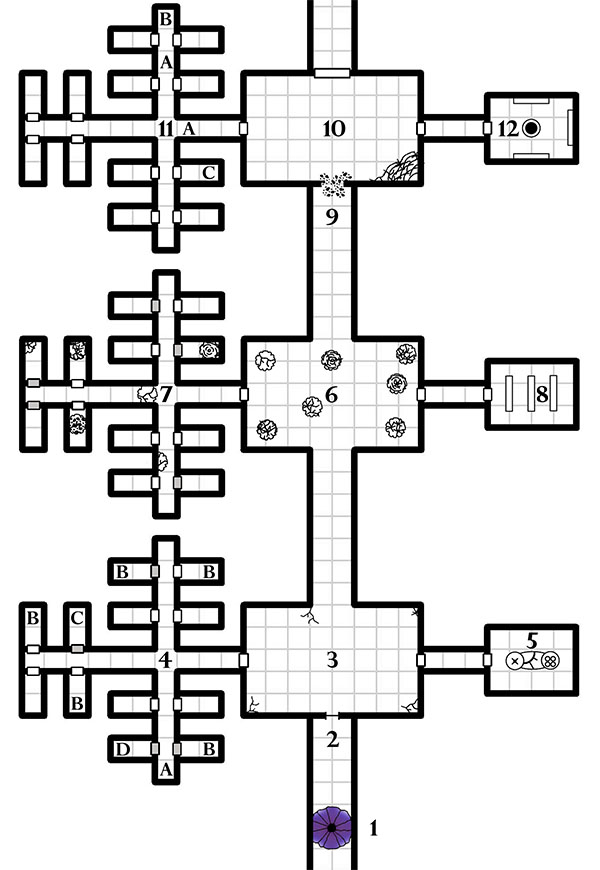

The bulk of the book is made up of the “City Guide”, which is broken into sub-sections each describing one of the city’s ten districts. Virtually everything in the book — NPCs, locations, etc. — is grouped into these districts, but the district you’re currently in isn’t indicated by the page header, so as you’re flipping through the book it’s impossible to orient yourself. Worse yet, the districts are presented in a completely random order.

The book contains no general index (a major failing), but does include a couple of appendixes, one of which lists which NPCs and locations can be found in each location. This helps a bit, but there’s not really any logic to where the NPCs are listed (particularly generic NPCs): Sometimes they’re listed where they live; sometimes where they work; sometimes it seems as if they were just placed in a district that was otherwise a little light on generic NPCs.

Information is also just kind of randomly scattered around, without any cross-referencing. For example, on p. 126 the NPC description of Mayor Ward notes that, “A portrait of Ward hangs next to one of Curwen in the foyer of City Hall (p. 119); the resemblance is uncanny.” The page reference to City Hall is useful, obviously, but the problem is that neither the foyer nor the painting is mentioned in the description of City Hall. (It’s possible that the “foyer” here is a reference to the “Main Rotunda” in the City Hall description, but if so that’s just another example of the book’s inconsistencies.) So if the PCs go to City Hall and you look up its description, you’ll never include the Ward and Curwen portraits.

The book is peppered with this sort of thing. Reading through it, I was constantly noting really cool details that I was confident would never make it into actually play unless I took the effort to work my way through the entire book and carefully annotate it.

Which, collectively, is the primary problem with Cthulhu City: Between the “choose your own setting” vagueries, the tack-on problem of frequently needing to do the bulk of the work to complete the vaguery, and the need to reorganize a large portion of the book so that it doesn’t go to waste, you end up saddling the GM with a workload roughly equivalent to writing the book in the first place.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

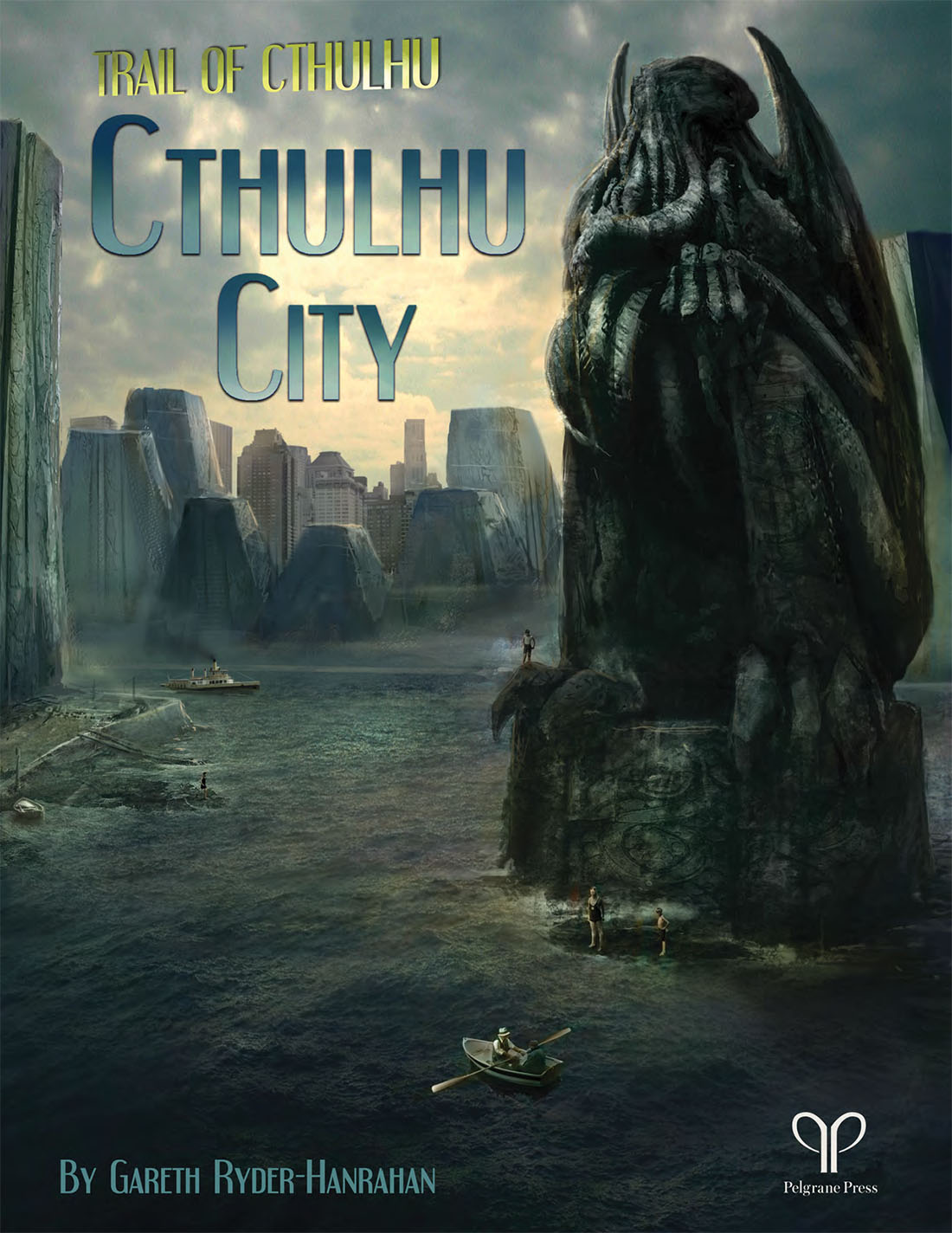

It’s also a shame that the illustrations in the book are so uniformly poor in quality: Boring compositions, atrocious anatomy, stiff poses, and crude in their overall execution. Another problem is that so many of the pieces appear to be (badly) attempting an “evocative” effect, which in practice means that they’re virtually always directly contradicting the description of the city given in the text. (Even the cover, which is gorgeous and, like so many of Jerome Huguenin’s paintings for Pelgrane, perfectly sets a mood, suffers from this problem by depicting a vision of the city which does not reflect that presented by the book.)

Cthulhu City is such a unique and unusual vision of the Mythos. It would have benefited greatly from a well-executed visual component.

The book also features an 18 page scenario. It’s a very good scenario, but one that is curiously unconnected with Cthulhu City. A few place names are dropped, of course, but these are all of a generic character and you could easily drop this scenario into literally any location without any effort at all. This is most likely an additional consequence of the “choose your own city” design of the book (a scenario would necessarily need to deal with specifics, and therefore it cannot interface with any of the characters, organizations, or locations described in the book without locking them into one form or another), but it’s another missed opportunity to provide the GM with clear direction.

(But, to reiterate, it’s a very good scenario: Clever, horrific, and almost certain to be incredibly memorable. If nothing else from Cthulhu City ever reaches my table, this scenario certainly will.)

Also: Maps without keys. Drives me nuts.

CONCLUSION

I’ve spent a large number of words discussing what holds this book back from greatness. But I don’t want that to necessarily detract from the fact that the book is very good. When I say that it’s brimming with ideas, features a fantastic scenario, and positively sizzles with a uniqueness which is all the more remarkable because it is enhanced by the well-worn elements which somehow add up to a whole so much larger than the sum of its parts… all of that is true.

And all of it is a very good argument for why you should immediately buy a copy and start devouring its contents as quickly as possible.

But…

I am, personally, held back from giving Cthulhu City my full-throated endorsement because, at the end of the day, I recognize that the book’s flaws add up to a sufficiently bulky workload that I will almost certainly never actually use any of it.

Which, ultimately, is enough for me to drop the Substance score by a full point and, with a heavy heart, slide the book onto my shelf to collect dust.

Style: 3

Substance: 3

Author: Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan

Publisher: Pelgrane Press

Print Cost: $34.95

PDF Cost: $20.95

Page Count: 222

ISBN: 978-1-908983-76-3

Great Arkham.

Great Arkham.

Wizardesses, and Assorted Practitioners of the Magical Arts.

Wizardesses, and Assorted Practitioners of the Magical Arts.