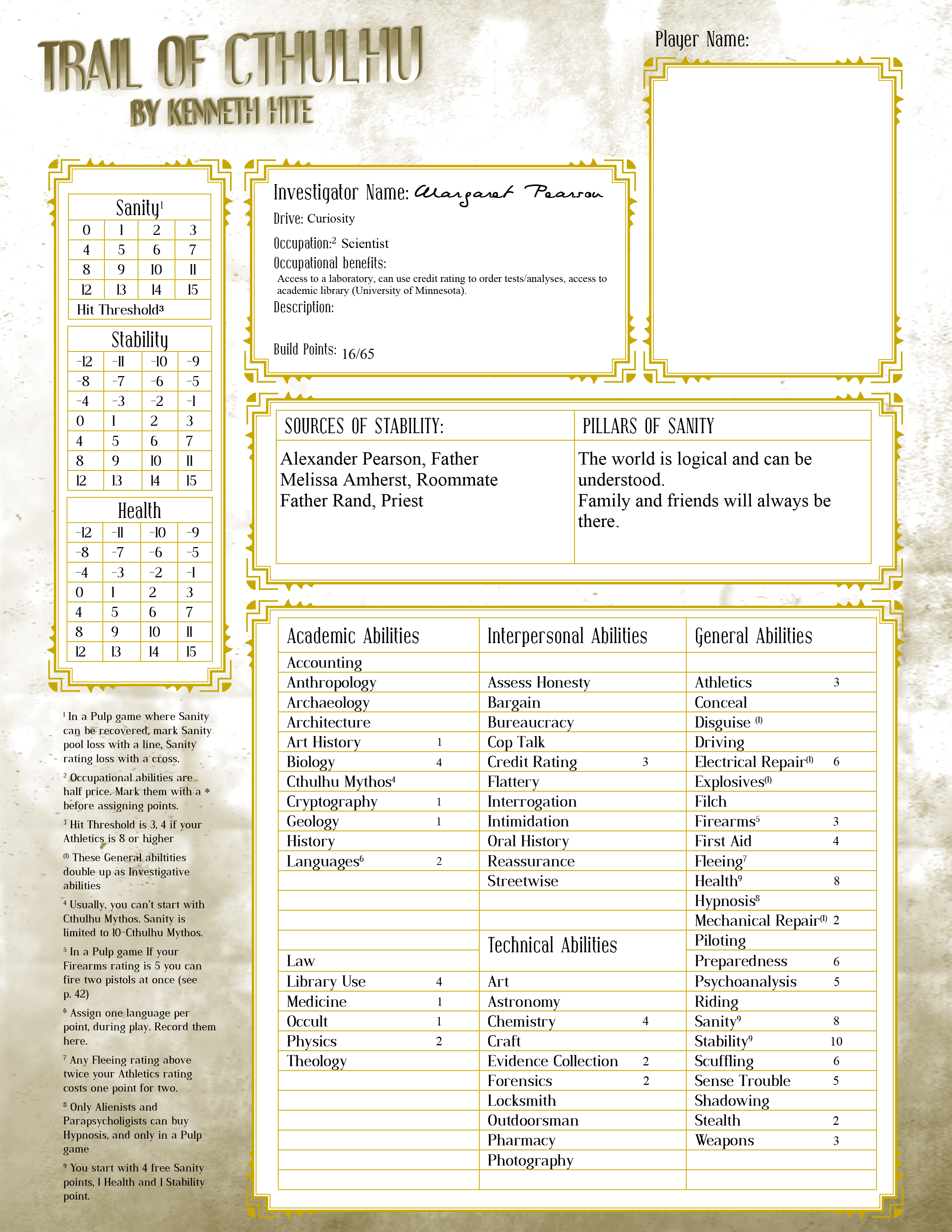

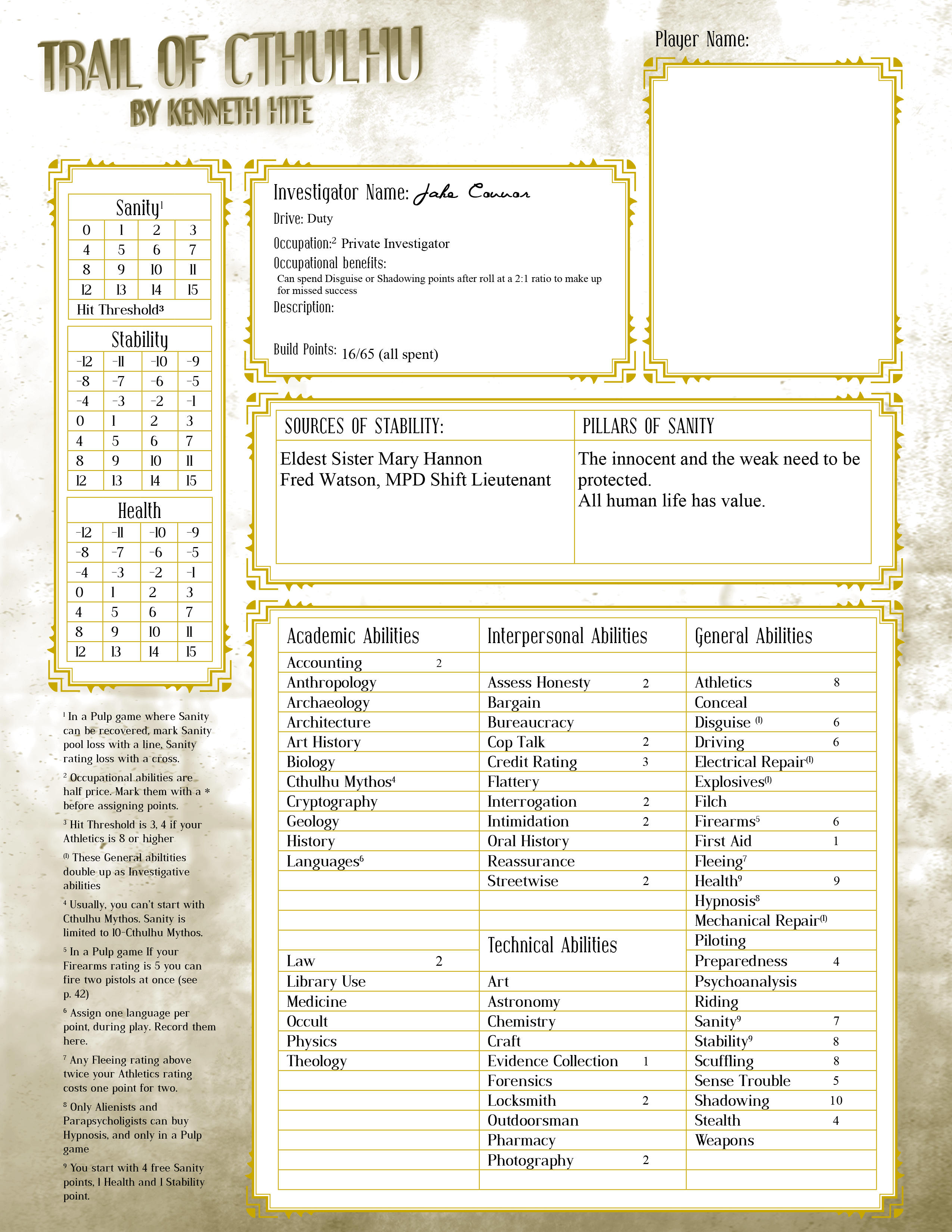

Mythos fiction tends to be well-stocked with mysterious tomes filled with enigmatic lore. When running a good Mythos adventure, you’ll often want to drop similar tomes into the hands of the players.

Broadly speaking, there are two structural functions these tomes can fulfill.

First, they can deliver a specific clue — i.e., you read the book and discover that athathan panthers can only be harmed in moonlight.

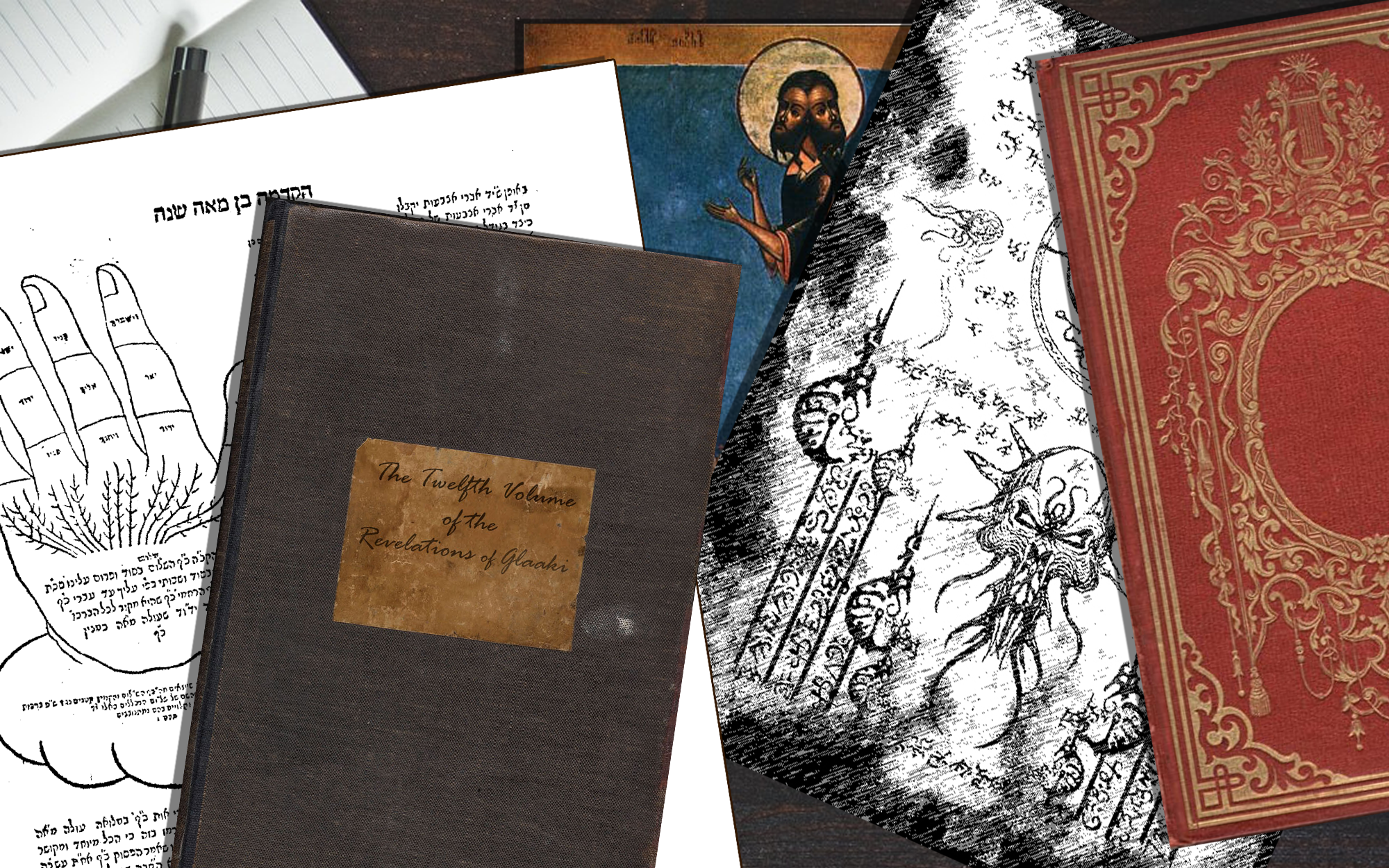

Second, they can provide a research resource. These are books like the Necronomicon, Nameless Cults, Tobin’s Spirit Guide, or The Revelations of Glaaki that are an arcane repository for a great mass of Mythos lore. Characters can refer to them time and time again across disparate investigations, and often find useful references.

TOME AS CLUE

If you want the tome to impart a specific clue (or clues), you might simply cut to the chase and give them the clue: “After staying up late into the night poring over the strange, bloodstained book you found on the altar, you unravel a ritual for summoning athathan panthers in exchange for human sacrifices. The victims must be sleeping and the ritual must be performed in moonlight, because that’s when the athathan are weakened.”

But this is also exactly what lore book props are designed for. That link will take you to a full description of how lore books work, but the short version is that they’re a kind of executive summary of fictional books. The experience of “reading” a lore book prop is more immersive for the players, particularly because you can embed the clues you want them to find in the description of the book, so that they can actually extract them from the text for themselves.

The trick with lore books is that, by their nature, they tend to deliver a lot of information in a single package. As a result, it can be easy for them to tip over into the neatly organized summary of what’s going on that we specifically want to avoid when designing Mythos scenarios. So you want to make sure, when writing Mythos lore books, that they remain a confusing and contradictory source text: A mythological understanding of mythology as transcribed by madmen. The longer text doesn’t necessarily bring more truth; it just gives a more dizzying array of mythological angles all looking at the same truth.

Another technique I’ve found useful is to identify one specific slice of the Mythos entity in question (i.e., the clue you’re trying to deliver), focus entirely on that one slice, and then build out a micro-story around it that’s largely or entirely unrelated to the rest of the Mythos entity. (For example, to convey some information about L’rignak’s strange matter, you could create a story found only in the unredacted, original manuscript of Sir Richard Burton’s Arabian Nights that deals with some orphan boys in Persia who find the strange matter in a cave and bring it home to the ruination of all who interact with it. The name L’rignak might not even be mentioned in this text.)

This technique can be quite effective at evoking the scope of the Mythos entity: The suggestion that it is not some new manifestation, but has rather always been entwined with human destiny. A great, strange mass which has made its presence felt throughout the world and history, but whose true immensity has never been glimpsed… until now.

TOME AS RESOURCE

The basic idea behind a tome that serves as a research resource, on the other hand, is that, if the PCs can rifle through the text, then it can help them to both “know” things and also figure things out. The exact mechanical representation of this will depend on the system you’re running (and possibly the tome in question), but a fairly typical structure looks like this:

Studying. Before the tome can be utilized as a resource, the PC must spend some time familiarizing themselves with it (e.g., a day, a week, a month, or until they succeed on a skill check of some sort).

Mechanical Benefit. Once the PC has studied the text, they gain a mechanical benefit when using it as part of a knowledge-type check. For example:

- They gain advantage on relevant checks.

- They gain a pool of points they can spend to enhance relevant checks. (Either once per scenario or a set pool that, when expired, suggests that the book’s usefulness has come to an end / the character has completely learned its contents.)

- The PC gains a permanent bonus to a knowledge-type skill or similar ability.

Usually a list of topics covered by the book determines which knowledge-based checks the book can be used to enhance. (For example, Tobin’s Spirit Guide might grant bonuses to checks related to the afterlife, undead, strange gods, and transdimensional travel.)

Cost. Books that reveal things man was not meant to know can be inherently dangerous, and it’s not unusual for studying a Mythos tome to inflict a cost (usually along the lines of lost Sanity or attracting the attention of powers who can sense those who know the Truth).

These tomes can also be presented as lore books, and, in fact, it’s ideal if they are. In addition to the list of topics covered by the book, you want to understand the nature of the book well enough that it can serve as a convenient vector for improvising where the knowledge came from. (Nameless Cults, for example, is primarily a study of cults by Friedrich von Junzt written in the 19th century. So if, for example, the PCs pull information about werewolves out of it, then the GM might relate the information via a lycanthropic cult in Prussia.)

CREATING TOMES

Of course, some tomes might be both: They provide an initial clue relevant to the scenario where they’re first encountered, but can also serve as a general resource for future research. (In other words, the initial clue is built into whatever the fictional frame of the book is.)

As you’re creating your own tomes, I generally recommend not making any single tome so vast in its contents that it becomes universally useful. Unless you want one specific tome to be the pillar around which the campaign is built, it’s generally better to break information up and spread it across a multitude of sources: First, it motivates the players to continue seeking new knowledge. Second, the disparate sources given you a multitude of vectors for coloring and contextualizing information as it flows into your campaign. Third, this diversity in sources also makes it to improvise interesting angles for presenting the information. The more generic and all-encompassing a source becomes; the more it becomes a bland encyclopedia, it follows that referencing the work becomes more and more like a blank slate.

If you’d like to see copious examples of what Mythos lore books look like, the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies contains literally dozens of them, including:

- Books of the Los Angeles Cult (both the UCLA Lot and Echavarria’s Library)

- Savitree’s Research

- Revelations of Glaaki (found in the Severn Valley props packet)

This vast number of tomes, however, should not be mistaken as model for how many lore books you need in your own campaign. The Alexandrian Remix is a special beast, and in practice a little can go a long way. In fact, it can be preferable for such lore dumps to be rare, making each lore book the PCs get their hands on a rare and precious prize.

On the other hand, for a truly hypertrophic of how far lore tomes can be pushed, consider the examples of The Dracula Dossier and The Armitage Files. The latter, designed for Trail of Cthulhu, is an entire campaign built around the players being given dozens of pages from “real” in-world documents and then puzzling their way through them to identify leads to pursue in their investigations. The former, designed for Night’s Black Agents, pushes the technique even further, “unredacting” the entire epistolary novel of Dracula and recharacterizing it as an ops file from British intelligence complete with marginalia and, once again, inviting the players to pore through the text to identify a multitude of leads.

I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, this is not so surprising.

After all, everyone knows that reading a Mythos tome can drive one mad.