BACKTRACKING DALAKHAR

Once the PCs identify Dalakhar as the primary target of the explosion, they may want to try backtracking his activities.

A successful Charisma (Investigation) check can track him back to the Inn of the Dripping Dagger, located in the Trades Ward (location T3 on the 3rd Edition City of Splendors map). He rented his room for one night and then left.

HIS ROOMS: Inspection will reveal that his room was scrubbed clean in a very professional fashion. A DC 12 Intelligence (Investigation) check will reveal ash in the base of the room’s oil lamp suggesting that a piece of correspondence was burned. (It can’t be reconstituted through non-magical means, but was Renaer’s response to Dalakhar’s original missive setting up the meeting at Trollskull Manor.)

Laying out in plain sight on the pillow, however, is a round disk of black stone painted with Xanathar’s stylized beholder sigil. It’s a death mark, left here as a threat after Xanathar’s minions tracked Dalakhar here.

XANATHAR RESPONSE TEAM: The room is also being watched by a Xanathar response team (see Part 3C). If they see the PCs enter the room, they’ll most likely accost them and see what they know about Dalakhar.

If it’s been more than a day since Dalakhar was killed, the response team has been briefed on that and is also aware that “the boss knows a guy name Floxin – one of those Zhent bastards – was following that gnome dungbag; the boss has got eyes on Floxin now”.

(This might give the PCs an alternative route to the Gralhunds by tracking down and following Urstul Floxin. Putting in some more legwork might discover that Floxin is currently operating out of Yellowspire (see Part 3B), and they might be able to follow him from there to the Gralhund Vila.)

If it’s been more than three days since Dalakhar’s death, the response team is pulled from this location.

THE LETTER: Four days after Dalakhar’s death, a letter arrives at the Inn of the Dripping Dagger for him.

Dalakhar,

I had to give considerable thought to your request. But you were always kind to me even when your demonic master was not. If you are still in need of my aid, you may claim whatever sanctuary I can offer.

Kalain of the Nine Waters

Before he was killed, Dalakhar was thrashing around trying to find whatever aid he could. He was even desperate enough to contact Kalain, a former mistress of Lord Dagult’s. Inquiries can identify Kalain’s place of residence in the Sea Ward.

DESIGN NOTE

The late arrival of the letter is designed to push a clue to PCs after their initial visit: Those who leave their names with the owners of the Dripping Dagger, particularly those who specifically ask the owners to contact them if any new information crops up, will be rewarded with a proactive follow-up. (Alternatively, but probably less likely, it can reward PCs who follow-up on old leads.) Since the clue is non-essential for the current investigation, the slightly heightened risk of them missing the clue is offset by the benefit of adding depth to the game world: Little details like this make the players feel as if the game world is a fully functional, living environment that persists beyond their immediate line of sight. (Largely because that is, in fact, what you’re doing.)

KALAIN’S TOWER

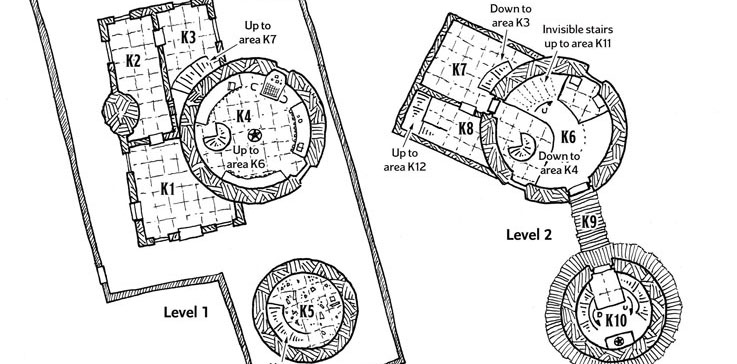

Kalain lives in a dilapidated tower in the Sea Ward. See Dragon Heist, p. 88, although the Vault is not secretly located there.

AREA W8 – KALAIN’S STUDIO: Here are Kalain’s most recent paintings, documenting her descent into madness.

- DOCUMENT LOCKBOX: A document lockbox with three drawers sits on one of the tables (DC 13 Dexterity check to unlock). One of the drawers contains love letters she exchanged with Lord Dagult. Another drawer contains similar letters, but these have been torn to confetti. (She periodically removes a letter from one drawer, rips it to shreds, and deposits it in the other.) The third drawer contains a number of work papers left behind by Lord Dagult (see below).

KALAIN

Appearance: A beauty ruined by tragedy; lines of sadness are etched into her face. Long black tresses are streaked with silver turning to gray.

Roleplaying:

- Believes everyone is secretly an assassin sent by Dagult Neverember to murder her.

- Loses track of the conversation and abruptly starts talking about completely different subjects.

- Rubs her cheek with her hand with increasing vigor as she becomes distressed.

- Will activate creatures from her smaller, older, more peaceful paintings to assist her (fetching small objects, etc.).

- Sees Dagult, Waterdeep, and the monsters of he newer paintings as all being the same thing; will refer to them interchangeably.

- Speaks of Neverwinter as if she were a red-headed maiden who seduced Lord Dagult from her arms. Occasionally confuses Neverwinter and Alethea Brandath.

Background: Kalain, a famous Waterdavian painter, was commissioned to paint a portrait of Lord Dagult Neverember, then Waterdeep’s Open Lord, in 1475 DR. Her meeting with Neverember marked the beginning of a torrid affair that lasted over a year.

Their relationship faltered as Dagult’s visits to Neverwinter became more frequent and extended. He made promises to Kalain that he failed to keep, and when she raised the subject of a faithful commitment, he treated her poorly, for his true love was Neverwinter. Kalain became enraged after Dagult’s rejection and turned to painting monsters that, in her mind, represented him. Her power to harness the Weave clings to the fabric of her works, giving her the ability to bring these monsters to life on her command.

Ultimately Neverwinter left Kalain a little over four years ago. He used his influence to ruin Kalain and divorce her from Waterdeep’s high society. She was allowed to keep her home, but her works and her reputation were destroyed, slowly and methodically. Kalain’s spirit was broken, leading to the onset of madness. Now she locks herself away, content to let time erode the last of her conscience.

Key Info:

- She knows that Dalakhar was a spy working for Lord Dagult Neverember. He sent a letter requesting her help, but she waited several days before replying due to her bitter history with Neverember.

- If told that Dalakhar was killed, she will blame the PCs for killing him on Neverember’s orders and then rapidly escalate to concluding they’re here to kill her (unless they quickly talk her down)!

- During their final days together, Lord Neverember was obsessed with a “Melairkyn ceremonial temple or religious vault or something like that. He was always more focused on anything else rather than me. Rather than us.” If questioned, she can provide the papers described above.

- If asked if she knows where the “vault” is located, she will become quite distressed: “I should know this. He was fixated on it. It would make me so angry… so very, very angry… And now I can’t remember why.” (She was irrationally jealous because it was his ex-wife’s tomb, but because of the Stone of Golorr she can’t remember that any more. No one can.)

- If specifically asked, she will recount speaking with the Lord Victoro Cassalanter about Lord Neverember and the vault a few weeks ago, but she won’t otherwise volunteer the information.

Stat Block: CE half-elf bard (DH p. 195).

- Art Imitates Life: Kalain touches one of her paintings and causes its subject to spring forth, becoming a creature of that kind provided its CR is 3 or lower. The creature appears in an unoccupied space within 5 feet of the painting, which becomes blank.The creature rolls initiative when it first acts. It disappears after 1 minute, when it is reduced to 0 hit points, or when Kalain dies or falls unconscious.

LORD DAGULT’S PAPERS

These papers mostly concern minor (and now thoroughly outdated) affairs of the city. There are a few pieces of unusual interest, however:

- A list of otherwise banal, crossed out tasks includes “move the dragon to the Melairkyn ceremonial vault.”

- Correspondence with Hammond Kraddoc of the Vinterners’, Distillers’, and Brewers’ Guild making it clear that Kraddoc gave Lord Dagult large bribes to cover up a scandal involving contaminated liquor in the Dock Ward.

- Notes apparently pertaining to a “ceremonial vault” built by the Melairkyn dwarves beneath Waterdeep centuries ago. The notes detail that such vaults were built by worshippers of Dumathoin, the Keeper of the Mountain’s Secrets. The dwarven cult believed that Dumathoin encoded his secrets in the veins of ore and precious stones he placed in the mountains he raised from the earth for the dwarven people. In their mining, the dwarves would release Dumathoin’s secrets into the world. This angered Dumathoin and there was a period of discord between the dwarves and the Mordinsamman (the council of dwarven gods). In order to appease Dumathoin and to protect his secrets, the cult would mystically bind the “secrets of the mountain” into items of finely-wrought dwarfcraft and then make offering of it to Dumathoin by securing them within ceremonial vaults. Such vaults, according to an ancient source, can be opned by “standing before Dumathoin’s doors and striking the scale of a dragon with a mithral hammer in the place where the sun’s light should fall.”

- An unsigned letter written to Lord Neverember four years ago stating that “the last of the three Eyes has been secured.”

- A letter from Dalakhar also dating to four years ago, reporting on his unsuccessful efforts to infiltrate the Enclave of Red Magic in the Castle Ward. (GM Note: This is literally a red herring. Dalakhar’s assignment four years ago has nothing to do with present events. The Red Wizards of Thay use the Thayan embassy as a cover for their local operations; it’s connected to the Thayan enclave in Skullport via a portal.)

DESIGN NOTE

I found Kalain to be a really fascinating character. For a long time, unfortunately, I couldn’t figure out how to fit her into the Remix. I eventually struck on the idea of having Dalakhar write to her for assistance so that the PCs could backtrack him and find a trail to her. Originally, I thought this would be a dead end: The PCs would meet an interesting character and get filled in a little bit more on the back story of the scenario, but there was nothing Kalain could offer towards their current investigation.

And then, in one of those glorious instances where creative thoughts heap one atop the next, I realized that there WAS a way that Kalain could contribute materially to the scenario. (It also allowed me to link to her from the Cassalanters, too, making it more likely that any given group will encounter her.)

Neverwinter is destroyed when a small adventuring party (including Jarlaxle Baenre) awoke the primordial Maegera beneath Mount Hotenow.

Neverwinter is destroyed when a small adventuring party (including Jarlaxle Baenre) awoke the primordial Maegera beneath Mount Hotenow.