Mythos-style horror is a pervasive theme in RPGs. It’s tough to get it right.

On the one hand, you don’t want everything to fall into random weirdness. The essence of Lovecraftian horror is the slow discovery of a monstrous and palpable truth shrouded from human perceptions. Plus, it’s just not as much fun for the players when everything in a session is capricious. It’s difficult to have meaningful gameplay or player agency when the game world is incomprehensible noise.

On the other hand, the players also shouldn’t be able to achieve a perfect understanding of what’s happening, either. I’m usually a pretty big advocate of “prep stuff so that you can show it to your players” – if you’re making something cool, let the players in on it! – but the Mythos is an exception. Perfect understanding of the Mythos renders that which should be too vast for human comprehension into mundanity.

The Mythos is also not the only place such ineffability may be desirable. For example, Numenera takes place a billion years in the future, after eight mega-civilizations which mastered incomprehensible technology have risen and fallen on Earth. The default setting is a Renaissance of sorts, in which mankind searches through the numenera – the broken technological remains of these mega-civilizations – while being unable to truly understand it. In this, Numenera is a sort of inverted Mythos, possessing the same sense of enigma, but generally (although not always) filled with hope instead of horror.

Regardless of tone, the technique I use for Mythos-style revelations is to think of them as three layers.

LAYER 1: CANONICAL TRUTH

For each Mythos element, start by clearly and concisely summarizing the “definitive” truth of it. Because this is Mythos stuff, this will still be weird, supernatural, mind-bending, alien to human thought, and probably even self-contradictory, but it’s your personal canon.

For example:

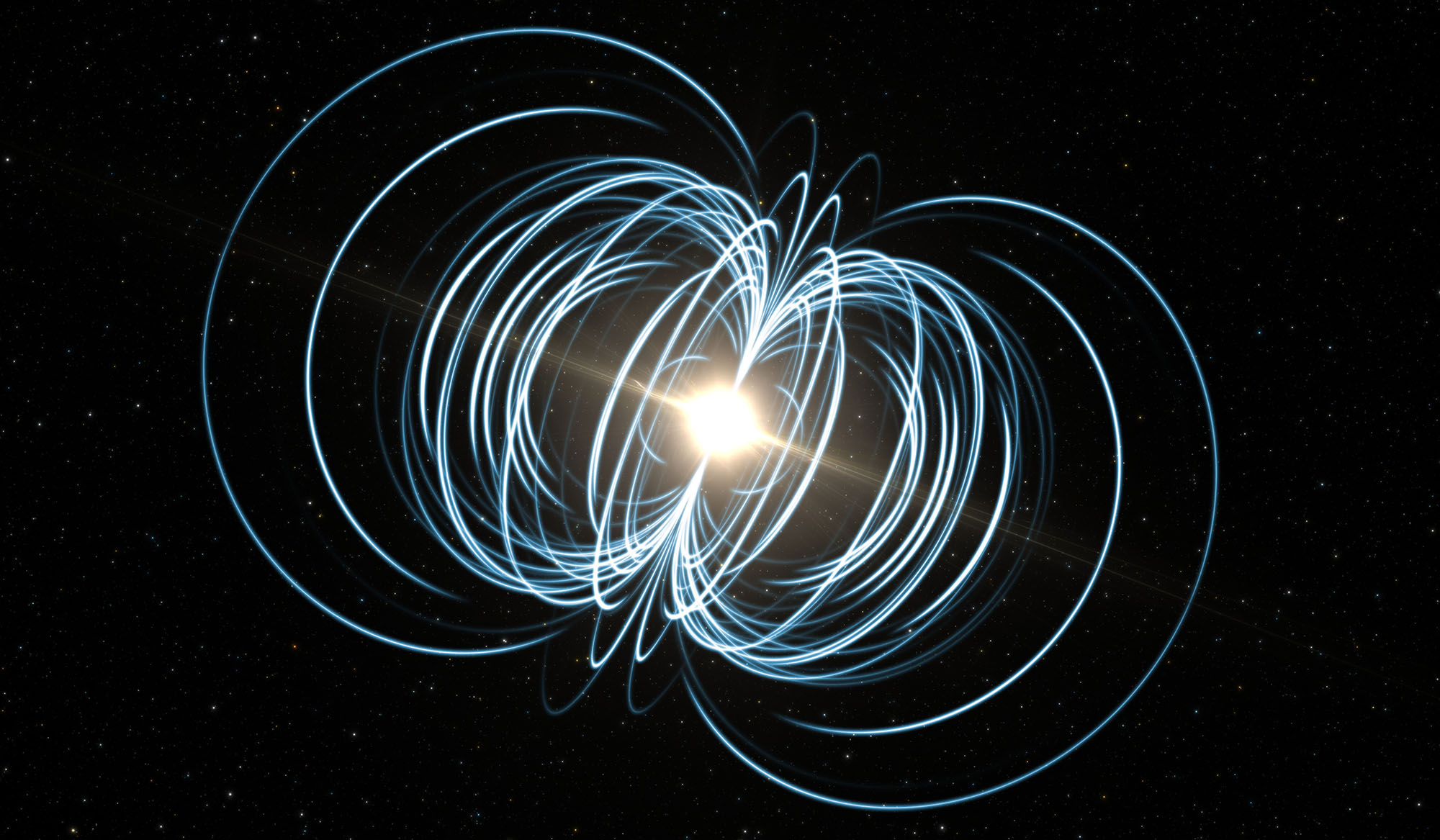

L’rignak is a multidimensional creature that lives in the heart of neutron stars. It seeks to colonize other stars. It also creates Great Attractors, either to form new neutron stars or to create whatever the structure is in the Laniakea Supercluster. (Is this an even greater mass into which it hopes to seed its consciousness some day? Or perhaps it’s already its seat of consciousness and the neutron stars are merely nodes or perhaps incubators for its offspring?)

Given proper conditions, L’rignak can open microscopic portals to the heart of its neutron stars. Strange matter erupts from these and they usually affect local gravity in strange ways. In our local spacetime, its greatest goal is to alter the sun (possibly be seeding it) to become an attractor (or otherwise start its impossible path to becoming a neutron star).

L’rignak’s cultists often speak of a time “when the sun’s light is made right.”

This is your lodestone, and it will keep you oriented even when “reality” transcends into the incomprehensible. It’s a guide that you can refer to and extrapolate from when prepping and running your scenarios. It’s scripture that lets you ask, “What would L’rignak do?” It’s the bedrock that everything else will be built on.

But the players will NEVER discover this plain, definitive truth.

LAYER 2: THE LENS OF MYTHOLOGY

Instead, you’ll break your canonical truth into chunks – i.e., each definitive statement or fact about the Mythos element. Then you’ll want to mythologize each chunk.

What I mean is that, for every chunk, there should be multiple interpretations, and these interpretations should be arcane, alien, and ineffable. Think of yourself as the blind men trying to describe an elephant — one grasps its trunk and describes it as a snake; another the legs and says it’s a tree; a third its ear and think it’s a kind of fan. You are trying to express TRUTH, but you can only do so through an imperfect lens.

To approach this mythological quality in a more practical way, it may be useful to think in terms of:

Paradox. Describe Mythos elements in impossible dualities. A darkness that illuminates; a vast, bulking mass of solidity that seems to float and ooze over the rocks; a warm glow that inflicts hypothermia. The impossibility, of course, is the point. The paradox cannot be resolved. Or, more accurately, it cannot be resolved within the limits of our human senses and science.

Dialectic. Along similar lines, think in terms of a truth reached through the resolution or confrontation of contradiction. When pointing your double-slit spotlight at the strange matter of L’rignak, for example, don’t just give the PCs the notes of a scientist grappling with “elements unknown to human science.” Also give them the heretical Christian texts describing it as “the flesh of god”; the cultist’s mad ravings about “the apocalypse’s gift”; and the strange references in Nameless Cults to “manifestations of faerie circles.”

Ironic Specificity. You don’t need to reveal the totality of your Mythos element. (At least not now, and possibly not ever.) But, importantly, you want to do so in a way that hints at the whole which is never revealed.

For example, your L’rignak scenario might focus exclusively on the eruptions of strange matter in the Appalachian Mountains that are harvested, worshiped, and turned to gut-churning purpose by the ancient cults there. The star-born nature of L’rignak and its transgalactic agenda are never brought up, except that when the PCs first interact with the strange matter they have an immense, cosmic vision, the afterimage of which momentarily leaves the stars in the sky knit together in a kaleidoscopic quilt of lightless lasers; a darkness that illuminates and seems to sear their eyes before it breaks apart into dark globs and then fades into the small, black spots that always seem to float through your vision. (Invoking the cosmic dimensions of a Mythos entity, of which — like the tip of an iceberg — only a small part can actually be seen to manifest clearly in our local spacetime, is quite common with this technique.)

This specificity can also manifest in historical, arcane, or scientific sources the PCs pursue even when you’re intending for the PCs themselves to have a more holistic experience. You can imagine 19th century scholars examining strange matter eruptions or Kepler’s secret notes documenting “strange novae,” with neither grasping that they’re only looking at an elephant’s trunk through a funhouse mirror.

Multiple Titles/Names. We label reality and give names to things because it gives us an illusion of control and understanding. We nail the winged thing to a bit of thick paper and label it a “dragonfly” and it’s no longer an enigmatic visitor from the realm of the fey, but rather something which has been fully compassed by our minds; classified, categorized, and neatly settled.

Defy this sense of understanding by invoking many names and titles for the same thing. L’rignak, for example, was known to the Aztecs as Tōnatiuh. They are also the Dark Star, the Psychopomp of Shapshu, and the Coming Night.

Parable, Allegory, Analogy. When the human mind struggles to grasp something, it will often try to find parallels within its experience to try to grapple with its meaning. This can easily give you a multitude of angles to approach the Mythos element from, but it’s also useful to think about useless and/or warped trying to apply an analogy of human experience to the fundamentally inhuman can be. (For example, don’t shy away from invoking paradoxical analogies.)

I find it can be particularly effective to think about how pre-Enlightenment science (or lack of science) might have attempted to grapple with these impossible truths. For example, modern science might talk about the “mutagenic effects” of some of L’rignak’s eruptions of strange matter, and how they rewrite mitochondrial DNA, creating a new structure that appears to enslave the host cell with chimeric properties. But older sources might describe them as a “fifth humour,” demonic possession, or the “font of godshead.” (Was the Oracle at Delphi a manifestation of strange matter?)

Confusion/Shaded Truth. The PCs are not the only ones incapable of understanding the Mythos element, so as they encounter other characters and sources attempting to describe it, it’s okay for a “truth” to be colored by falseness — apocrypha and flawed translations accumulating over centuries and corrupting the original statement.

This was the primary approach when the players in my In the Shadow of the Spire campaign wanted to research the name “Saggarintys,” which they had encountered in the Banewarrens. (SPOILER WARNING!) The true version of events was that Saggarintys the Silver King was a silver dragon who worked with the Banelord to construct the Banewarrens, a vast vault in which artifacts of great evil were to be sealed away from the world. The Banelord eventually became corrupted by one of the artifacts, betrayed Saggarintys, and imprisoned him in a cube of magical glass.

Saggarintys was not, therefore, an ineffable Mythos entity, but I knew that he had lived so long ago that any contemporary references they found would be fragmentary at best. So I could use a similar mythologizing process and when the PCs did their research, what they found was:

In the fragmentary remnants of the Marvellan Concordance there is a reference to “Saggarintys, the wanderer of the West” or “from forth the West” (depending on the translation). There is some speculation that this may indicate that Saggarintys is an archaic name for the Western Star.

(This is rooted in the fact that dragons came from the West in my campaign world. So Saggarintys was literally “from forth the West,” but this is then colored with the false conclusion that this is a reference to the Western Star.)

The name appears on Loremaster Gerris Hin’s list of “Allies of the Banelord.” A “Saggantas” is also referred to as the Secret Lord of the Banewarrens.

(Here the name has been corrupted into “Saggantas” and Saggarintys’ role as the Architect of the Banewarrens has caused his identity to become conflated with the Banelord. Note the multitude of names and titles.)

Saggarintys, the Silver King, is the name of a legendary sword said to be the Destroyer of Banes.

(The mythologization is heavy here: The seed of truth is that Saggarintys was opposed to the evil artifacts known as banes and may even have researched how to destroy them. I imagined chivalric tales interpreting “destroyer of evil” as obviously referring to some powerful weapon. Another influence here is the Sword of Truth, a holy artifact that was used in the construction of the Banewarrens and, thus, was another “enemy of the banes” that could have gotten mixed up with Saggarintys.)

A children’s rhyme from Isiltur describes Saggarintys (later shortened to Saggae or “Silver Saggae”) as a friendly spirit who lives in the Land of Mirrors and aids youngsters in need.

(Here the glass prison of Saggarintys is interpreted as a mirror and the context is shifted to a children’s story, naturally warping the nature of the narrative.)

LAYER 3: WHAT THE PLAYERS SEE

You’ve broken your canon into jagged, overlapping pieces and mythologized them, but this still isn’t what the players actually see at the table. Even if they conduct research at Miskatonic University, they won’t get a neatly organized fact sheet summarizing the mythology.

Instead, what they’ll find – through research, investigation, interrogation, or supernatural manifestation – are clues.

In fact, you can often think of all those jagged, mythologized pieces as a revelation list. Note that, even though these revelations are mythologized, they can still be practical and actionable (e.g., “go to a room without corners to avoid the Hounds of Tindalos”).

Like any revelation list, of course, you’ll want to respect the Three Clue Rule. However, as you’re crafting these clues, I recommend being a little more, let’s say, poetic than usual.

In the modern world we often think of poetry as just being “pretty words,” but the heart of poetry is the difference between comprehending something and apprehending something. Comprehension is when you rationally work your way to a conclusion, but apprehension is when you seize hold of a truth through a sort of instinctual sense. It’s the music that accompanies the lyric and a factor beyond the literal sense of the passage. It’s an intersection of ideas and also the transcendence of meaning.

The best clues often suggest a conclusion rather than spelling it out. What I’m suggesting here is that, for these Mythos revelations, you can consciously choose to evoke that suggestion instead of expecting logical inference. Perhaps moreso than with other revelations, I also recommend strongly differentiating the clues pointing to a single revelation, with each evoking the truth of that revelation in distinct ways. This will encourage the players to poetically synthesize the disparate imagery of those clues, creating “truths” that are grasped only in silhouette and which change and shift as each new clue is added to the picture.

This can also be extended to the revelations themselves. Sufficient mythological bifurcation might result in the same canonical concept becoming two “separate” revelations. (Such revelations might even contradict each other.) Maybe the players never realize the connection between these revelations, or maybe they can perform the intuitive dialectical leap and synthesize some common ground of “truth” for themselves (which may or may not resemble what you “know” to be the canonical truth those revelations were extrapolated from). Either way, mission accomplished.

As you can see from the examples above, it’s likely that the mythologization process itself will begin generating, or at least strongly indicating, some of these clues (e.g., there are references to L’rignak in Nameless Cults). In fact, as this suggests, the clues themselves will be formed from an additional cycle of mythologization. They should be indirect, arcane, and contradictory understandings of the revelations (which are, themselves, an indirect, arcane, and contradictory understanding of the “truth”).

The corollary to all of this is, once again, that the clues are the only thing the players will ever definitively learn. And so your players will ultimately be staring at a mythology (the obscured “truth” of Layer 2) through the lens of mythology (the clues of Layer 3). There are, therefore, multiple interpretations built atop multiple interpretations, which will naturally lead the players to begin creating their own interpretations, no two of which will perfectly align.

Perfect understanding becomes impossible, but it will also feel like it’s just out of reach. The players will feel as if they can surely come to grips with this forbidden knowledge… if only they stare into the Abyss a little longer.

And that, of course, is exactly what you’re looking for.

Looking at this, I’m thinking how a good starting point to layer 2 might be Multiple Titles/Names through the lens of Paradox and Ironic Specificity. I.E. what are some different, conflicting concepts that the subject might be known as. L’rignak might be known as a god, a physical concept and a place.The Aztecs talk about Leignathotl, the god of living darkness who grants true believers the ability to fly. A german physicist talks about a corruptive energy “Düren’s Licht” which seems tied to certain remote localities. A seer from the 1890s talk about Lirak, the darkness beyond where the new gods dwell.

Making sure that the multiple names are about different concepts entirely can constrain what I feel would be a normal inclination to just make it a list of different gods/spirits.

This also creates a strong contrast for when the PCs are just told something straight. There are higher beings that would be happy to explain what’s going on in the mythos… you just might not want to meet them.