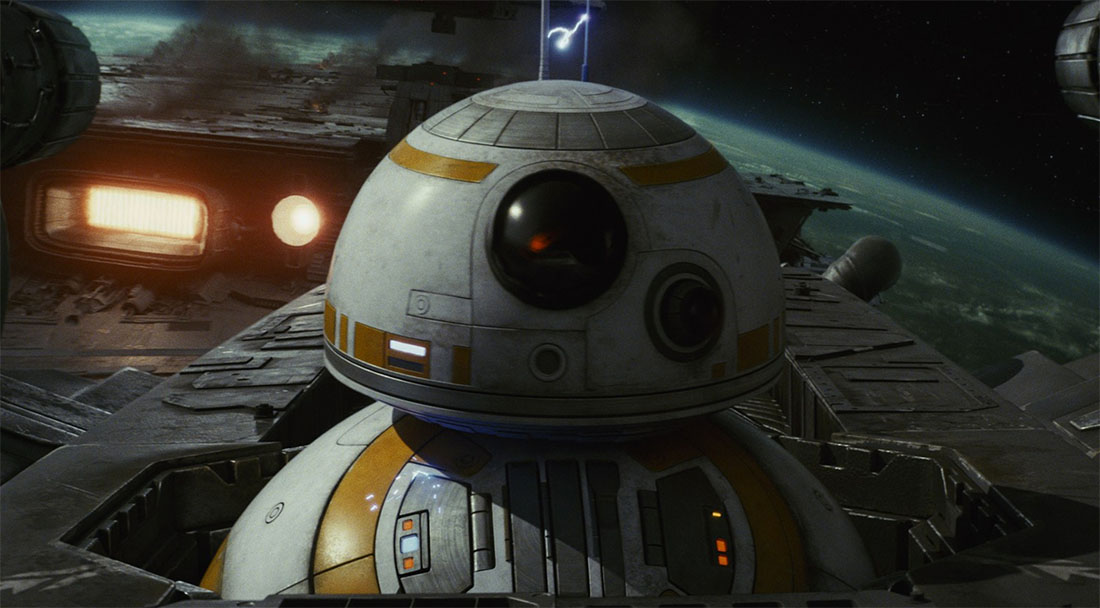

The Last Jedi has proven to be a controversial and divisive movie. What is perhaps most surprising is the degree to which both sides of the conversation seem to be simply incapable of believing that the other side exists and are obsessed with disenfranchising their opinion: Those who liked the movie are convinced everyone who says they didn’t are either mindless fanboys, Russian bots, or racist misogynists. Those who disliked the movie are convinced everyone who says they did are either mindless fanboys or paid Disney operatives.

I’ve found myself somewhat in the middle as far as these discussions are concerned. (Which, of course, means that I’ve spent all my time being broiled alive by both sides.) So let’s talk about The Last Jedi.

SPOILERS AHOY!

There are eight significant clusters of criticism for the film:

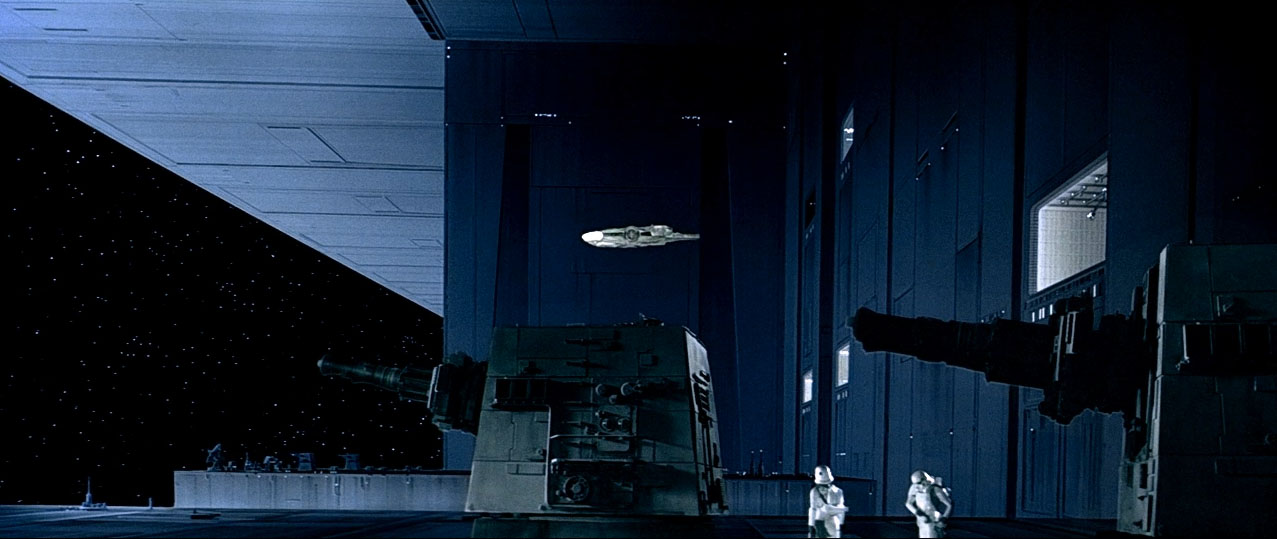

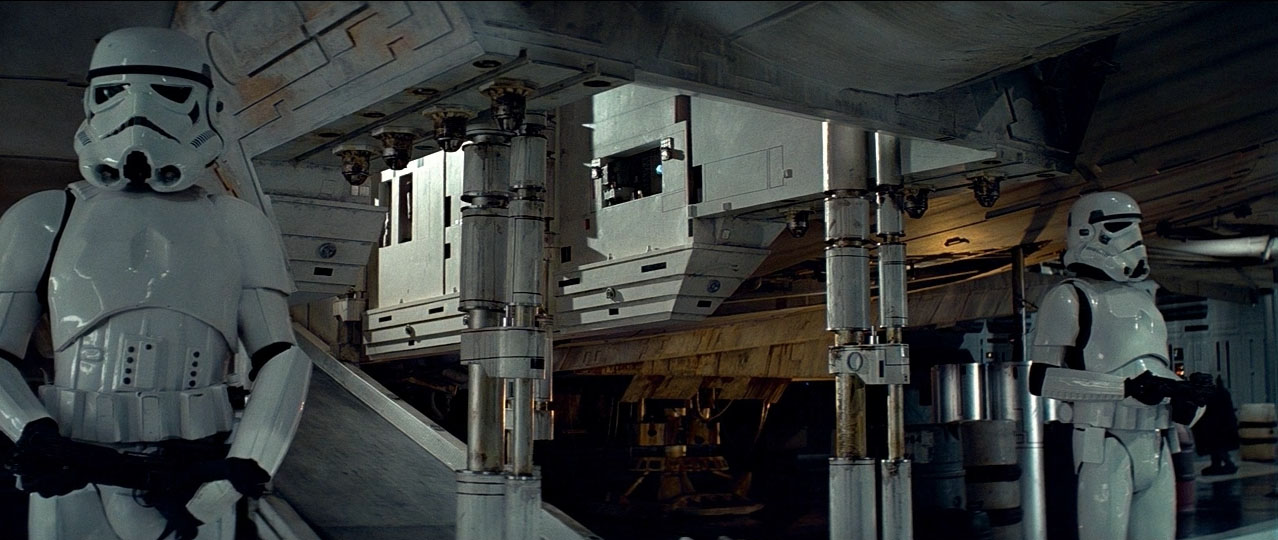

- As The Last Jedi begins really building on top of the decision in The Force Awakens to completely reboot the Empire vs. Rebellion conflict, it’s become clear to many people that they really hate this decision. (This includes people who didn’t like The Force Awakens for the same reason.)

- This nihilistic reboot methodology also extends destructively to the OT characters, each of whom are revealed to have been the most complete, utter, and abject failures imaginable in every single facet of their lives – personal, professional, political – and are then set up to be systematically killed off one movie at a time. (A scheme only somewhat derailed by Carrie Fisher’s death in real life.) This is, to put it mildly, leaving a really bad taste in people’s mouths.

- The primary plot (of the cruiser chase) is riddled with plot holes and doesn’t make any sense. The film suffers because its backbone is broken.

- There is an assortment of special edition/prequel-style humor which is not landing for many people (titty-milking, confetti Praetorian guard, “General Hugs”, etc.).

- Material that fans feel is inconsistent with and untrue to the canon which has preceded this film. One prominent sub-cluster here is Rey’s ability to perform astonishingly powerful Force tricks while receiving no training whatsoever.

- Several plot threads end with the heroes failing to achieve their goals. (Many critics describe these plot threads as being “pointless”, but this is one point where I’ll editorialize by pointing out that “failure” and “pointless” are not synonymous in cinema. More on that in a little bit.)

- “But my pet theory! But my speculation! But my shipping!” The Last Jedi is not consistent with (and some feel even deliberately contemptuous of) many of the popular fan theories that followed in the wake of The Force Awakens.

- WTF is up with all these women and minorities fucking up my movie? (Actually, I’ll editorialize here again: Fuck these people.)

From this list, in addition to #8 (seriously, fuck those people), I’m also going to summarily dismiss #7. First, from a purely factual point of view, Rian Johnson finished writing his script and began pre-production for The Last Jedi before The Force Awakens was ever released. The personal “slight” that some people are perceiving because their personal pet theories didn’t pan out has no basis in reality: Johnson was faced with the same conundrum you were and came to different conclusions.

Second, this general trend in fandom is not a healthy one in any case. For example, shipping as a fun little thing to do as fans / while writing fan fiction is cool. The toxic version where fans rage against the dying of the light when their ships don’t pan out is a cancer on modern media.

IT’S REVOLUTIONARY!

Let’s also dispatch with something else straight out of the gate. I am really sick of being told that a film in which:

- The rebel’s base has been discovered and they need to evacuate

- A young Jedi goes to seek an old master who has retreated to a remote planet because a former student turned to the Dark Side (and then discovers that the old master lied to them about their former student!)

- The heroes seek help from a charming rogue only to have him betray them

- There’s a confrontation between the Disciple of Light and the Disciple of Dark in front of the Emperor’s… err… Supreme Leader’s throne

is some sort of revolutionary Star Wars story the likes of which has never been told before.

It isn’t.

Get over it.

DESTRUCTIVE NIHILISM

By far the largest problem that I, personally, have with this film are the first two points above: The sequel trilogy is fundamentally built on a brutally nihilistic foundation. And that’s not even Rian Johnson’s fault: He took what The Force Awakens gave him and he followed it through to the logical conclusion. He’s ruthlessly effective at it, in fact, and, honestly, it shouldn’t be any other way. Ultimately the sequel trilogy is what the sequel trilogy is going to be; fighting against that now would only result in an increasingly incoherent narrative.

That doesn’t make me any happier about it, though. I think it’s an abominable handling of the Star Wars legacy. Instead of building on what came before, the sequel trilogy diminishes it.

By contrast, the prequel trilogy, for all of its flaws and foibles, never diminished the original trilogy. If anything, the prequel trilogy greatly enhanced the original trilogy. (Primarily due to narrative leitmotifs like the character arcs of Anakin and Luke, although that’s perhaps a topic for another day.) The same cannot be said for the sequel trilogy: The revelation that everything achieved in the original trilogy has been turned to ash and the heroes of the original trilogy are complete and utter failures is incredibly damaging to the ending of Return of the Jedi and, in fact, the entire narrative arc of the first six films. Six films all led up to a moment where Luke Skywalker transcended the teachings of the Jedi and the teachings of the Sith and brought balance to the Force. The sequel trilogy fundamentally unravels that in order to “reboot” the original trilogy characters back to an earlier state of their existence.

If you accept the sequel trilogy as canon while watching the original trilogy, it makes the original trilogy films weaker and less powerful. And that’s really not okay, in my opinion.

Allow me a moment now to rebut a few common counter-arguments at this point.

“Everybody dies! This was inevitable!”

Yeah, sure. But not everybody dies after seeing their entire life end in abject failure.

“You just wanted the original trilogy heroes to be perfect paragons without flaw!”

Not at all. This is a false dilemma. Luke, Leia, and Han can be flawed characters who make mistakes without being complete and utter failures. And it would be far more interesting to see Luke, Han, and Leia all continue to grow as characters from the point where we left them at the end of Return of the Jedi than it is to see them all get nihilistically rebooted to either earlier stages of their lives or into a cheap Ben Kenobi rip-off.

“You can’t have peace! The movie is called Star Wars!”

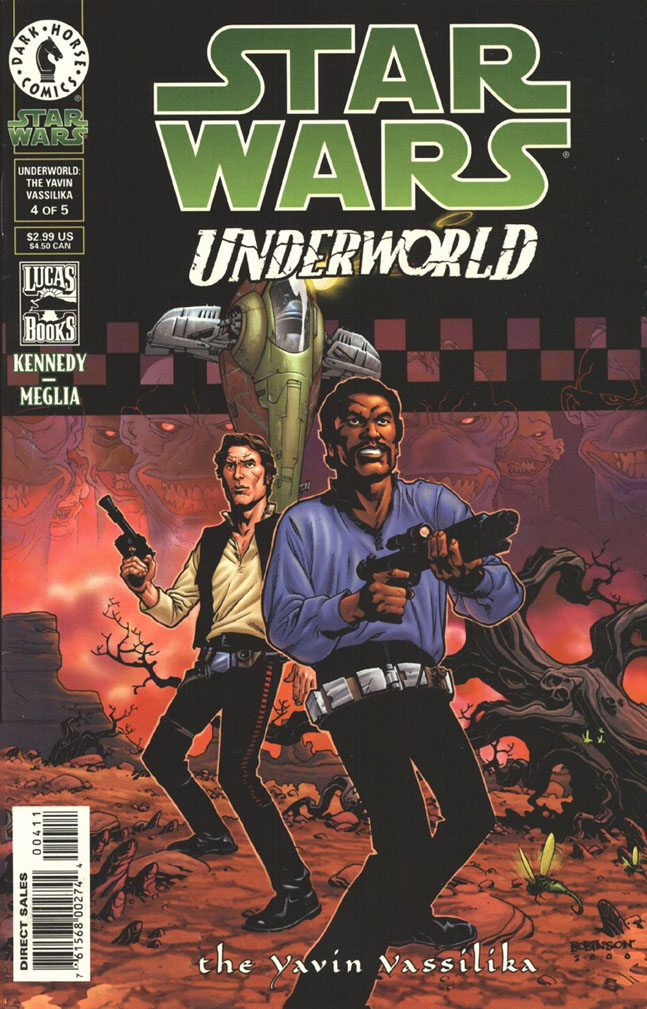

This is another false dilemma. If you don’t reboot the Empire vs. Rebellion conflict, the alternative isn’t automatically a peaceful galaxy filled with happy unicorns frolicking through fields of flowers. The alternative is an infinite variety of OTHER options which aren’t destructively nihilistic to the Star Wars legacy: Palpatine Loyalists rebelling against the New Republic. A cold war in a galaxy divided between the Imperial remnant and the New Republic. Droid War. Extra-galactic invasion. Cryogenically frozen Sith army from 10,000 years ago waking up.

The sequel trilogy simply lacks ambition.

Now, as I’ve mentioned, these problems were already present in The Force Awakens. That movie laid down the destructive foundation of the sequel trilogy. But The Last Jedi really starts building on that foundation, owns what that foundation means, and begins telling a story that drives home the consequences of that foundation. I think that’s the primary reason why it’s bearing the brunt of people’s ire for this nihilism.

Similarly, I thought I’d come to terms with the sequel trilogy “reboot” after The Force Awakens. But leaving the theater after seeing The Last Jedi I had to grapple with the fact that I had not, in fact, done so. The conclusion I eventually reached was that for me, personally:

The sequel trilogy is fan fiction.

Albeit fan fiction with a fantastic budget.

Consider what Mark Hamill said in a recent interview:

I almost had to think of Luke Skywalker as another character. Maybe he’s Jake Skywalker. He’s not my Luke Skywalker. (…) We had a fundamental difference. But I had to do what Rian wanted me to do because it serves the story. Listen, I still haven’t accepted it completely.

Like Hamill, I couldn’t accept this movie as being a “real” part of the Star Wars saga. And so… I’ve chosen not to. And, at least for me, once I made that choice, when I went back to see The Last Jedi again, I was able to really enjoy the film for what it is by itself. Because once you get past the destructive nihilism on which it is built (or simply bypass that entirely by severing it from all that has come before), what you have is a really great movie.

Jake Skywalker, for example, may not be Luke Skywalker. But Jake’s story is really amazing and filled with some incredibly powerful moments once you accept that he isn’t Luke Skywalker and his story is not going to be coherent with Luke Skywalker’s. (For example, “And the last thing I saw were the eyes of a frightened boy whose master had failed him.” is an incredibly powerful idea, perfectly scripted with phenomenal line delivery, and complemented by perfect and beautiful visual framing… It’s just brilliant. It also has no business having Luke Skywalker in it.)

THE PROBLEMS I HAVE

The destructive nihilism, however, is not the only problem the movie has. We’re particularly going to look at points #3, #4, and #5 above, because that’s the cluster that sums up where I think the movie falls short.

The first 7 minutes of The Last Jedi include:

- The “General Hugs” comedy bit.

- Poe taking out all of the surface cannons of a dreadnought solo, while flying an X-Wing which moves unlike any other Star Wars spaceship ever filmed. (It looks as if he’s driving a drag racer from Fast and the Furious.)

- The poorly delivered “Wipe that nervous expression off your face” line.

- The utterly bizarre “fix a computer by smashing it with your head” comedy bit.

- The bit where all the bombers were flying in such a close formation that when one was taken out they were all taken out.

Also, fine, bombers “drop” bombs in zero-g because the spaceships fly like World War II fighter planes. But the bomb bay doors are open to the vacuum of space, and something like 5 minutes later Leia is going to be sucked out into space because of the vacuum. Set a rule and follow it. I stand corrected (see the comments). This still bugged me in the moment, but I was wrong to be bugged by it.

Watching the tonally-deaf special edition-style humor for the first time in the theater, the thought honestly crossed my mind, “I might have to walk out of this movie.”

Fortunately things improved from there, but there are still a number of problems with the film, most notably the central chase sequence around which the entire film is built.

- We’re slightly faster, but for some reason that doesn’t translate into “getting ever farther away”; it translates to “we can maintain this very specific distance”

- The First Order has multiple ships, but they can’t just have some of them do an FTL jump to pen the rebels in.

And so forth. Basically, I think if you’re going to make a dilemma like this the central pillar on which your entire film is built, you need to make the effort to make sure it actually makes sense. When you fail to do that, everything you build on top of it becomes rickety.

Having firmly concluded that the ship chase sequence was built on nonsense, however, I was surprised when watching the film a second time that in the absence of my brain gnawing away at the logistics of the chase sequence, I was able to sort of accept the “reality” of that chase sequence and instead appreciate the intricately woven character arcs built atop it.

CANTO BIGHT

Which brings us to Canto Bight (aka, the Casino Planet).

Oddly, I’ve found a great deal of criticism surrounding the film’s focus on this sequence. It’s apparently “pointless” (because it results in failure) and should have been cut from the film.

Which I find utterly bizarre because Canto Bight is absolutely essential to the movie.

Like all of the best Star Wars stories, The Last Jedi thrives on its characters. (Which is why the fundamental swing-and-a-miss on the core characters from the original trilogy is causing such immense blowback. But I digress.) And for Canto Bight there are two key character arcs to consider here.

First, Poe’s. This consists of four specific beats:

First, Poe’s. This consists of four specific beats:

- Make a mistake by pursuing a course of reckless heroism instead of strategic leadership in the bombing run. (He then gets called out by Leia specifically for doing this, clearly establishing this as a central idea in the film. She even says, “I need you to learn that.”)

- Make the same mistake on an even larger scale by disobeying Holdo’s orders and putting the entire Resistance at risk.

- Learn from that mistake, and demonstrate that learning process during the skimmer battle on Crait. (“It’s a suicide run. All craft move away! … Retreat, Finn! That’s an order!”)

- Apply the lesson which has been learned by realizing that Luke is buying them time, and then leading the survivors out of the cave instead of leading an assault on the First Order. (A decision which is then very specifically endorsed by Leia – “What are you looking at me for?” – who established this arc in the first place, thus signaling that Poe has been successful in learning this lesson and has been rewarded with the leadership which was also foreshadowed as the prize for doing so.)

The Canto Bight sequence only has an ancillary impact on Poe’s arc, but I bring it up because it’ll tie back into Finn’s arc in a second. Finn’s arc begins back at the beginning of The Force Awakens and is built around Hierocles’ conception of oikeiôsis, in which humans extend their sense of self in ever-widening concentric circles:

in which humans extend their sense of self in ever-widening concentric circles:

- He wants to survive.

- He extends that desire to Rey.

- He extends that desire to the Resistance (i.e., the actual men and women who are in peril on the Resistance’s ships).

- He transcends that desire and becomes a Rebel; one who will fight for what is right to the benefit of the entire galaxy. (This culminates in, “Rebel scum,” which is a fantastic inversion of that line.)

In order for Finn to achieve that final bit of growth, he cannot be stuck on the Resistance transports. He has to go out into the galaxy and truly see the consequences of not standing up to the First Order. He has to see the oppression. That doesn’t necessarily need to be Canto Bight (there are other forms of oppression that could have been depicted), but the setting works well due to the strong contrast between luxury and oppression.

(This is also a good junction to note that the Canto Bight sequence is not particularly long. It takes up only 11 minutes of the film and is very briskly paced.)

The other aspect of Canto Bight is Rose. She doesn’t have a strong personal arc (because she’s a supporting character), but she plays a really important role as Finn’s guide and teacher.  Not by actually, literally teaching him shit, but by being the living embodiment of ideas and experiences that he needs to process. Canto Bight is, once again, essential for this because it provides the tapestry on which Rose’s character is revealed, and it is by seeing Canto Bight through Rose’s eyes that Finn learns the lessons he needs to learn.

Not by actually, literally teaching him shit, but by being the living embodiment of ideas and experiences that he needs to process. Canto Bight is, once again, essential for this because it provides the tapestry on which Rose’s character is revealed, and it is by seeing Canto Bight through Rose’s eyes that Finn learns the lessons he needs to learn.

What’s interesting here is that Finn’s growth up to this point has only taken him as far as where Poe was at the beginning of the film: That’s why Finn disobeys an explicit order and attempts a suicide run on the cannon.

This is really amazing and subtle filmmaking for a couple of reasons:

- Finn has arrived at this point not by paralleling Poe’s character arc, but by perpendicularly coming to the same resolution. This adds depth and dimension to this aspect of the film. (In much the same way that, for example, Kylo Ren and Luke come to the conclusion of “let it all burn” from very different directions and for very different reasons after both ricocheting off opposite sides of the same moment).

- At the very moment that we’re seeing Poe demonstrate that he’s learned the lesson, we’re seeing Finn repeat Poe’s mistake from the beginning of the film. Thus there is a direct contrast that really lights up Poe’s growth as a character.

- Rose saves Finn and tries to communicate something really important (both to himself and this entire film): “That’s how we’re going to win. Not by destroying what we hate. By saving what we love.”

- Finn still hasn’t actually learned the lesson, though. So the moment at which Poe is fully incorporating the lesson and demonstrating his mastery of it (“He’s stalling. (…) We’re the spark that will light the rebellion.”), he’s simultaneously providing the final push Finn needs to get over the hump, learn the lesson, and get to the same point Poe is now at.

And what is that point?

What Poe just said: That it’s not enough to Resist. They must be the Spark which lights the Rebellion.

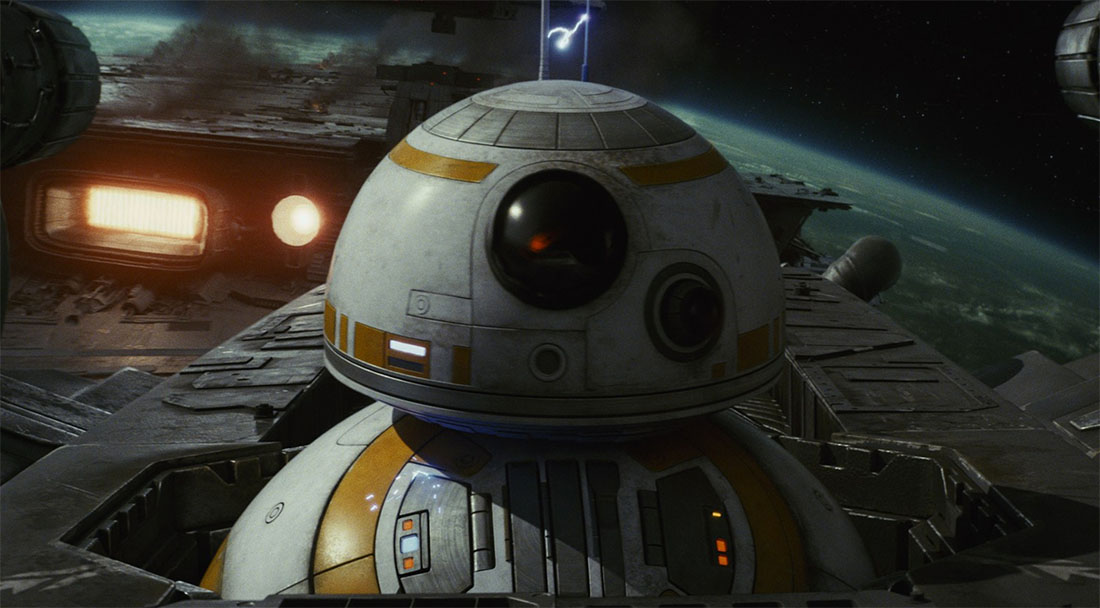

It’s arguably the single, most important theme of the movie, and these three characters have engaged in a beautiful dance through the entire film so that, rather than just talking about that “spark that lights a rebellion” we’ve seen that spark in action. And how that spark has transformed Poe and Fin (and, through a completely separate arc, Rey) into the Rebellion.

And the whole thing turns around the axis of Canto Bight.

CONCLUSIONS

Canto Bight isn’t the weak link in the movie. It’s an almost perfect example of just how good this movie really is.

Once you divorce The Last Jedi from the crippling flaw of utterly failing to build upon the Star Wars legacy (and, in fact, doing the exact opposite by inflicting terrible damage upon that legacy) — and, don’t get me wrong, that’s a really huge problem — and consider it strictly as a film on its own merits, what you discover is:

- Incredibly intricate and interwoven character development

- Fantastic performances from virtually everyone in the case

- Stunningly beautiful and effective cinematography

- At least a dozen moments that are absolutely iconic and incredibly memorable

But it’s this last bullet point that inexorably draws us back to that central problem, because for so many of those moments it would be more accurate to say that they would be iconic if they weren’t built on false foundations.

I’ve already mentioned how incredibly cool the “eyes of a frightened boy” moment is… if it didn’t feature Jake Skywalker masquerading as Luke Skywalker. To that we can also add things like:

- The spellbindingly captivating hyperspace ramming sequence… except that the hyperspace ramming itself (like the sudden ubiquity of never-before-seen cloaking technology) has problems syncing with everything we’ve seen in this universe previously and opens a Pandora’s box of future storytelling problems.

- The “spark which lights the rebellion” material is pitch perfect, deep, and incredibly effective… if it were part of a story set prior to A New Hope. (It makes the comparable material in Rogue One look almost hapless by comparison, and I liked Rogue One.) But here these themes simply attach a bullhorn to the destructive nihilism of the films with a screeching, “I’m fucking up the original trilogy almost as badly as the special editions!”. And, ironically, the more effective Johnson is in realizing this material, the more he cranks up the volume on the bullhorn.

And so forth. There are also, to be fair, a number of very good moments which land without any drawback whatsoever. (For example, Kylo Ren’s incredibly clever way of getting around Snoke telepathically monitoring him for betrayal.)

But there’s also a smattering of other foibles in the film, including a number of baffling continuity errors. (For example, the fact that Poe knows Maz is perhaps explicable despite never meeting her in the previous film. Poe having somehow never been introduced to Rey during their time at the rebel base at the end of The Force Awakens is not.)

So, here’s my final verdict: As a Star Wars film, The Last Jedi earns a D. Separated from the saga and treated as a form of indulgent fan fiction, I give the film on its own merits a B+.

If you can, like me, separate this film from its destructively nihilistic base through the simple mental expedient of saying #notmystarwars with positive instead of negative intentions, then I highly recommend The Last Jedi. It’s a wonderful and beautiful and powerful film.

But I won’t blame you if you can’t.

First, Poe’s. This consists of four specific beats:

First, Poe’s. This consists of four specific beats: in which humans extend their sense of self in ever-widening concentric circles:

in which humans extend their sense of self in ever-widening concentric circles: Not by actually, literally teaching him shit, but by being the living embodiment of ideas and experiences that he needs to process. Canto Bight is, once again, essential for this because it provides the tapestry on which Rose’s character is revealed, and it is by seeing Canto Bight through Rose’s eyes that Finn learns the lessons he needs to learn.

Not by actually, literally teaching him shit, but by being the living embodiment of ideas and experiences that he needs to process. Canto Bight is, once again, essential for this because it provides the tapestry on which Rose’s character is revealed, and it is by seeing Canto Bight through Rose’s eyes that Finn learns the lessons he needs to learn.