For our second scenario structure challenge we’ll be returning to the Star Wars universe, but to a decidedly more obscure example: Star Wars: Underworld – The Yavin Vassilika was a 5-issue mini-series produced by Dark Horse Comics in 2000-01.

For our second scenario structure challenge we’ll be returning to the Star Wars universe, but to a decidedly more obscure example: Star Wars: Underworld – The Yavin Vassilika was a 5-issue mini-series produced by Dark Horse Comics in 2000-01.

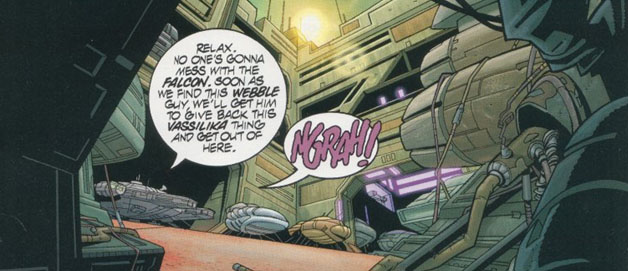

Star Wars: Underworld is not a great comic book, being primarily hamstrung by an artist with a delightfully detailed and stylized vision of the Star Wars universe, but whose panel layouts too often topple over the ledge of “creative” and go hurtling into the vast void of “incoherent”. But what the series does have is a really interesting premise that sets up an action-packed narrative.

The basic hook is that three Hutts learn that a long-lost and extremely valuable artifact known as the Yavin Vassilika is rumored to have been found (or, more accurately, located).

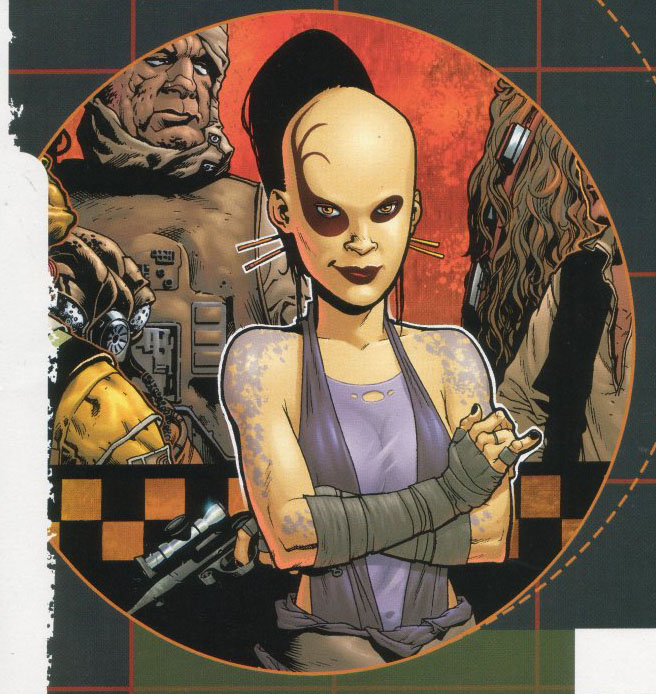

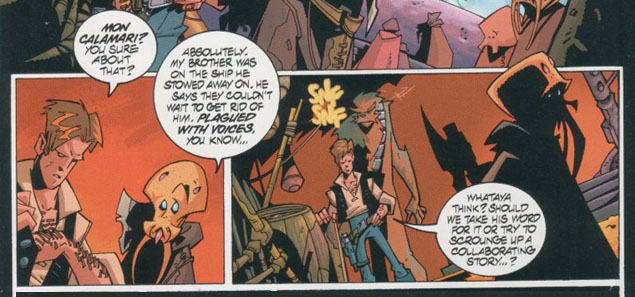

The Hutts decide to make a “friendly” wager to see which of them can obtain the Yavin Vassilika first, with each hiring a team of operatives to track it down. A number of familiar faces from the Star Wars movies and Extended Universe are split up across the teams (Han Solo, Chewbacca, Lando Calrissian, Greedo, Bossk, IG-88, etc.), and each team needs to track down Webble, the raving madman who claims to have seen the Yavin Vassilika; backtrack his recent movements to figure out exactly where the Yavin Vassilika is; and then secure the Yavin Vassilika.

Most of the action, of course, is driven from the teams interacting with each other: Spying on other teams, sabotaging their efforts, baiting them into following false leads, openly trying to kill them, and so forth.

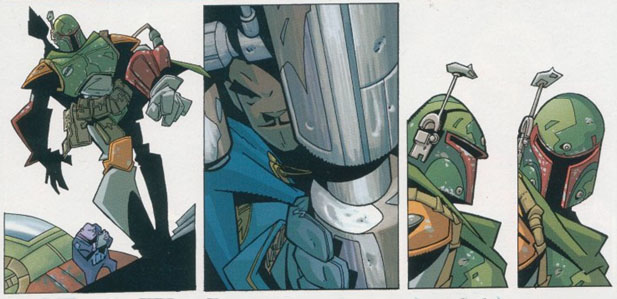

The story also utilizes an interesting cluster of sub-agendas. Some of these take the form of specific vendettas between the characters, but also in the more generic form of registered bounties that have been taken out on various characters. It’s under these auspices that Boba Fett enters the fray as an independent party seemingly uninterested in the Yavin Vassilika itself, but intensely interested in the people seeking it. The participants in the “race” are also able to take out (and buy-off) bounties on each other as the opportunities present themselves, creating an ever-shifting tangle of incentives.

The final wrinkle in all this is that, in addition to the Hutts, there’s another major player interested in the Yavin Vassilika: A mysterious figure known only as the “Collector”, but who also has an agent in the field. This agent primarily operates by trying to suborn the agents of the Hutts so that they’ll deliver the artifact to them instead of to their employer.

RACE TO THE PRIZE

The basic structure of Star Wars: Underworld is fairly easy to emulate:

1. Create X number of competing teams/agents. Star Wars: Underworld has, in addition to the PCs, two additional teams directly pursuing the McGuffin and two independent agents pursuing their own agendas (one trying to convince the teams to sell her the McGuffin; the other hired to secretly protect one of the hunters).

This is really the meat of the scenario. Create interesting foes and big personalities for the PCs to compete with and you should have a winner. You can also follow the lead of Star Wars: Underworld here and have the agents in the field working for a variety of employers who have competing agendas for the ultimate use of the prize.

2. Finding the McGuffin is a linear Three Clue Rule scenario, which is super easy to design.

You’ll probably want to make this chain at least four or five links long, giving the PCs plenty of time to jostle for position, conspire with, and be ambushed by the other factions. Making some or all of these links somewhat involved mini-scenarios will make it easier to intensify the stakes by bringing multiple teams into play. (You could also use a node-based structure instead of a linear one to add complexity to the investigation.)

Where this can get a little more interesting is that if you’re not the first group to find a particular clue, you can also just track the team(s) ahead of you and follow them to the next clue. In addition to the PCs investigating other teams, this also provides a motivation for other teams to be investigating them (thus prompting interaction between the teams).

In its most basic form, this is really all you need to run this type of scenario. Run the investigation scenario straight, but then throw in an appearance from a competing team whenever it seems appropriate to make things interesting. Don’t forget that the other factions are also in competition with each other and will have interactions that don’t directly affect the PCs, but may spill out onto them.

ADVANCED OPTIONS

But let’s look at a few advanced options we might use to enhance the experience.

BOUNTIES: As mentioned above, the original Star Wars: Underworld narrative includes a substrate of competition based around various members of the competing teams having bounties on  their heads. This provides secondary motivations that can complicate the simple rivalry between the teams and also allows for factions motivated by something completely different from the other factions.

their heads. This provides secondary motivations that can complicate the simple rivalry between the teams and also allows for factions motivated by something completely different from the other factions.

(You might think about other secondary objectives that can bring additional factions into play. Not just because that’s useful for creating additional factions, but because having factions pointed at different things – instead of all being pointed at the same thing – can make it easier for those factions to collide with each other.)

To set up a similar bounty system:

- Set initial bounties on some (but not all) of the participants in the race. (I’d suggest generally including at least one PC on this list.)

- Ideally, have a mechanism which allows PCs and other characters to quickly keep up to date on which characters have active bounties on their heads.

- Figure out how characters (particularly PCs) can place a bounty on another character’s head.

- It can also be useful for there to be a mechanism by which a PC (or other character) can remove the bounty placed on their head. In the Star Wars universe, bonded bounties can literally just be bought out. Another option might be that the death of the person who put the bounty on your head will result in the bounty being removed.

You’ll probably want to make sure that the PCs become aware of the bounty system fairly early in the scenario (or even before the scenario begins).

TIMELINE: Purely improvising the activities of a half dozen other factions in simultaneous operation with the PCs can be a tad difficult and may have unsatisfying results. One way you can prep the progress of the race is by laying out a simple timeline of how quickly the other factions reach various milestones in the scenario.

Like any timeline, of course, you’ll want to:

- Make sure you don’t spend a lot of effort prepping past the point at which the PCs will almost certainly have meaningfully altered the outcome of events. (I’d guess probably no further than the first two or possibly three milestones.)

- Alter and update the timeline as necessary in order to reflect the actions taken by the PCs (and the impact they have on other participants).

For factions that are pursuing goals tangential to the McGuffin search, their timelines might instead feature sequences of escalating interactions with the PCs (and also the other teams).

The benefit of objectively tracking the progress of the other factions is that it creates a hard deadline for the PCs; the resulting pressure will ratchet up the intensity of the scenario for the players. The advantage of prepping a timeline to accomplish this is that it’s relatively simple and straightforward, and also allows you to put some thought into the types of clues their off-screen activities might generate. The disadvantage is that it’s comparatively likely to result in a lot of wasted prep.

PROGRESSIONS: Alternatively, for some factions you may find that prepping a progression has more utility. Progressions are similar to timelines, but rather than pegging events to a specific time, each progression represents a sequence of actions that a particular faction might attempt.

For example, in Star Wars: Underworld the character of Jozzel could be given this progression:

For example, in Star Wars: Underworld the character of Jozzel could be given this progression:

- Offer Faction #1 300,000 to deliver the Vassilika to her in exchange for a fake that can be given to their Hutt patron.

- Attempt to seduce a PC in order to keep tabs on their progress.

- Plant a homing beacon on the ship belonging to Faction #2.

- If she gets the McGuffin, steal the PCs’ ship (or a ship belonging to another faction) and lead them to her secretive patron for the final exchange.

Progressions aren’t locked in stone, of course. In the case of Jozzel, during the “actual play” of our hypothetical gaming session, she ends up getting basically kidnapped by the PCs and dragged along by them for a good long while. Maybe the next time you run the scenario, she ends up getting killed by one of the factions and they leave her body in a location where it will frame the PCs for her murder.

In other words, just like timelines, progressions can easily get disrupted by PCs. But they can also be a little more flexible in practice, since their additional elements can often be brought back into play (often from an unexpected angle) even after the disruption (whereas the events on a timeline tend to be dependent on the previous events of the timeline).

On a similar note, you can also use weak progressions. These are really just a menu of “things this faction will do” without necessarily putting them in a specific sequence. Weak progressions are more difficult to use in practice because it means that you have more “balls in the air” so to speak, but they give a bigger menu for options of “what happens next” during actual play.

CHASE MECHANICS: Another alternative would be to create some form of mechanical structure for resolving the progress of each team towards the goal. Exactly what this would look like would depend on the system you were using to run the scenario, obviously, but the advantage would lie in giving the players a more direct feeling of control over the outcome of the race by giving them something more tangible to interact with and manipulate. The GM, for their part, would similarly be able to actively play each faction’s interactions with the chase mechanics.

RUNNING THE RACE

Upon reflection, running the McGuffin Race is not that dissimilar from using an adversary roster when running a dungeon; the difference is that rather than managing the activities of the adversaries geographically, you’re managing them temporally (and probably, for most GMs, with a healthy dose of dramatic timing).

If you go with the relatively straightforward options, you’ll have:

- The investigation for finding the McGuffin.

- A set of progressions for each faction, detailing their activities.

- Possibly a timeline for when other factions “hit” each milestone on the investigation.

Note that each of these can really be thought of as a separate linear sequence running in parallel with each other. (Even the investigation is just the linear framework which will form the backbone of the actions which the PCs choose to take.) So when you’re running the race, you just need to look at the top item of each of those lists and decide what happens next.

It seems big and complicated and chaotic, but structurally it’s actually easy peasy.

If you’re still struggling with how to make it all work in practice, try imposing a slightly more formal procedure on yourself:

- Each time the PCs finish a scene, take a moment to provisionally frame the next scene. (As described in The Art of Pacing, that means identifying the PCs’ intention, choosing obstacles, and skipping to the next meaningful choice.)

- Before committing to that scene, however, look at your progressions and pick 1-2 things that the other factions do before that scene takes place. (You can even roll 1d3-1 and randomly determine which factions take their next progression actions if you really want to provoke yourself in unexpected directions.)

Some of these actions won’t actually affect the PCs or what the PCs are doing right now. That’s fine. Make a note (mental or otherwise) that they’ve happened and move on to the next scene. The PCs will likely discover the consequences of what’s happened in a later scene.

Other actions will affect the PCs. Those are essentially obstacles standing between them and the scene they wanted to have (or the obstacle you had already anticipated for them): Frame up the new scene and run it. When that scene is finished, let the PCs proceed to their next scene (which may or may not be where they were headed before they got interrupted by the other factions). When that scene is done, repeat the process of seeing what the other factions are doing.

Also: Your progressions aren’t written in stone. As things develop in play, feel free to add (or insert) additional actions into the progressions of the other factions. You might also discover that certain situations will prompt factions to take actions that you didn’t prep onto their progressions. That’s obviously totally fine. Do what feels right and play each faction actively throughout.

BEYOND THE UNDERWORLD

For an additional exercise, consider analyzing Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as another example of this scenario type. The basic elements are a little more occluded here (particularly because so many of the factions are pretending to be allies when they’re really antagonists), but it can be a valuable example because the action is more strictly based around Indiana’s POV (which more closely emulates what the typical experience of PCs will be at the table).

Consider, also, Guardians of the Galaxy, which uses a micro-version of the structure to bring the PC party together.

It only lasts for a single scene, really, but you’ve got similar dynamics (including literal bounties as an alternative motivation for factions being involved). A scene like this obviously doesn’t need the full work-up described above, but within its tight confines it can be a useful object lesson in what makes these situations tick: Think about how much less interesting the scene would be if Rocket and Groot were also solely interested in the sphere, thus unifying everyone’s goals instead of having them work at cross-purposes.

Rare and magical artifacts are, obviously, not the only sort of McGuffin that can be targeted in the race which forms the backbone for this sort of scenario. Anything which must be searched for or obtained through a sequence of challenges can have a similar function.

A structure which at first glance seems the same, however, would be multiple teams competing at a single challenge simultaneously. An elaborated example of this would be multiple teams exploring the same dungeon at the same time. Although superficially similar, note how the lack of a series of shared chokepoints makes it much more difficult to bring the various factions into interesting interactions with each other. Despite their similarities, I think you’ll actually need a different structure to make this sort of scenario work smoothly and successfully at the table. (And that might be something we look at in the future.)

I’m curious about how you track the passage of time during play. This structure seems contingent on knowing how much time has passed between events, which can often be fairly arbitrary.

Most of the time, I think it’s just a matter of making reasonable estimates about how long something is likely to take and then making a ruling.

Off the top of my head, here are some situations where something more formal than that would be appropriate:

– When time spent is significant, but the time required for a task could vary based on competency (i.e., a high margin of success on a Gather Information check could allow you to get the info you need much faster). A formal structure is valuable here because it gives concrete benefit to mechanical abiltiies possessed by the PCs.

– When you’re using a scenario structure where action economy is significant. OD&D’s formal dungeon crawl structure is an example of this: It takes a specific number of actions to do various common dungeon-delving activities; and for every X such actions, a wandering monster check is made.

We’ll see a structure that could similarly benefit from a formal structure for action economy in the next installment of this series if all goes as planned. For the scenario structure described here, I would probably use “make a ruling” most if not all of the time. There’s so many things that the PCs could choose to do that I don’t think it could generally be meaningfully predefined; so any attempt to create such units would still boil down to the GM making a ruling, they would just be doing so, translating it into the “turns” or “rounds” or whatever, and then translating it back into real world terms.

One thing kind of hinted at in the article, though, is that there are other ways to think about time. Like, maybe the actual progression of real world time is largely irrelevant. The more meaningful question is, “While the PCs were doing X, how much could groups A, B, and C get done?”

This is sort of beside the point here, but you said in the article that you would make a linear three-clue-rule chain about four or five links long, is that with a choke point after every three nodes? like 131313131 or is it more like 1333331?

For purely linear it would be this:

But four or five nodes long between intro and conclusion. You can vary that up a bit, but by keeping it linear here you keep forcing the factions back into each other.

I recently watched a video by the Gentleman Gamer in which he describes a campaign scenario for a low-level Planescape game, consisting of a “Wacky Races”-style cross-planar scavenger hunt (sponsored by the Planar Trade Consortium for Fabulous Prizes) and I immediately thought of this article.

Regarding timelines, The angry GM has a great mechanic where he uses the (random) encounter tables as, essentially, a b-plot completely divorced from location. He doesn’t roll on the table randomly, but puts events in order of escalating interference with the PCs. He rolls randomly for when these events occur. This would work well in this scenario for the Boba Fett encounters:

1. Discovery of the bounty on your head

2. Clues that you’re being hunted

3. Surprise encounter with the hunter

4. Final showdown with the hunter

Reading through this I just realized one of the published adventures for the Warhammer 40K RPG, Rogue Trader, is one of these. The Adventure is call “Lure of the Expanse” and has the players attempting to reach a treasure planet called the Dread Pearl before several other factions do. Each is detailed in how differently they operate and how willing they are to make alliances.

The only issue I really have with it is that as written there is no benefit to getting to the Dread Pearl early because the planet is surrounded by a Warp Storm that can’t be passed until it weakens.

The main thing I like about it is that it isn’t scripted in how things go down. It provides several locations to visit, plenty of side-quests at each location, and each location has several pages of background written up to help inspire ideas as well as make judgement calls for the GM easier. In fact, I think it is actually the first adventure I read that was essentially node-based.

…I really want to run Rogue Trader now but my only consistently available player has no interest in Sci-fi RPGs and I just started a campaign for a person new to the hobby. The eternal pain of wanting to DM a game and having no one to run it for…