Over the past couple decades, a design concept that has become fairly entrenched in D&D culture is that the PCs need to face X encounters of Y difficulty per day. The general idea being that the game is balanced (either intentionally or unintentionally) around their resources being chewed up across multiple encounters: If they face fewer encounters, there’s no challenge because (a) they will still have lots of resources left at the end of the day (thus suffering no risk) and/or (b) they burn up LOTS of resources per encounter (making those encounters too easy).

There is obviously a kernel of truth here, but there are also, frankly speaking, A LOT of problems with this design ideology. But that’s somewhat beyond the scope of this article. What I’m mostly interested in focusing on today is one specific element of game play that becomes a really problematic dilemma when combined with this design ideology:

Wilderness encounters.

See, the basic assumption is that the design of Dungeons & Dragons should be finetuned around X encounters of Y difficulty per day in which the value of X reflects the number of encounters in a typical dungeon. There are some problems with this idea that dungeons should be designed as a one day excursion, but laying that aside, this makes a lot of sense: The dungeon is the assumed primary mode of D&D play; therefore the game should be balanced around dungeon adventures.

But, of course, the density of encounters in a dungeon is inherently much higher than the density of encounters in a vast wilderness. Furthermore, even if you increased the density of wilderness encounters, the result would be to turn every wilderness journey into an interminable slog. If you assume that

X = a dungeon’s worth of encounters = one day’s worth of encounters

then a wilderness journey that took ten days would “logically” have ten times the number of encounters in a typical dungeon.

You don’t want to do that, so you make one wandering monster check per day in the wilderness: The players know that they’ll have at most one “dangerous” encounter per day, so they just nova all of their most powerful abilities and render the encounter pointlessly easy.

So what do you do?

Do you just strip wilderness encounters out of the game entirely? They’re pointless, right? But to delete an entire aspect of game play (and something that routinely crops up in the fantasy fiction that inspires D&D) feels unsatisfactory.

Perhaps you could artificially pack one particular day of wilderness travel with X encounters, turning that one day into a challenging gauntlet for the PCs. But that’s really hard to justify on a regular basis AND it still has a tendency to turn wilderness travel into a slog.

For awhile there was a vogue for trying to solve the problem mechanically, primarily by treating rest in the dungeon differently from rest in the wilderness. In other words, you just sort of mechanically treat one day in the dungeon as being mechanically equivalent to ten days (or whatever) in the wilderness. The massive dissociation of such mechanics, however, could obviously never be resolved.

Long story short, the dynamic which has generally emerged is for wilderness encounters to be REALLY TOUGH: Since the PCs can nova their most powerful abilities when facing them and there is no long-term depletion of party resources (including hit points), it follows that you need to really ramp up the difficulty of the encounter to provide a meaningful challenge.

In other words, dungeons are built on attrition while wilderness encounters are deadly one-offs.

There are several problems with this, however.

First, it creates a really weird dynamic: Instead of being seen as dangerous pits in the earth, dungeons are where you go to take a breather from all the terrible things wandering the world above. That doesn’t seem right, does it?

Second, the risk posed by these deadly one-off wilderness encounters is unsatisfying. In a properly designed dungeon, players can strategically mitigate risk (by scouting, retreating, gathering intel, etc.). This is usually not true of wilderness encounters due to them being placed either randomly (i.e., roll on a table) and/or arbitrarily (“on the way to Cairwoth, the PCs will encounter Y”).

(A robustly designed hexcrawl can mitigate this, but only to some extent.)

Finally, this methodology – like any “one true way” – results in a very flat design: Every wilderness encounter needs to push the PCs to their limits and thus every wilderness encounter ends up feeling the same.

So what’s the solution?

THE FALSE DILEMMA

The unexamined premise in these attrition vs. big deadly encounters vs. skip overland travel debates is often the idea that challenging combat is the only way to create interesting gameplay.

Partly this is the assumption that all random encounters have to be fights (and that’s a big assumption all by itself). But it’s also the assumption that if the players easily dispatch a group of foes that means nothing interesting has happened because the fight wasn’t challenging.

Neither of these assumptions is true.

Let’s back up for a second.

You’ll often hear people say that they don’t like running random encounters because they’re just distractions from the campaign.

Those people are doing random encounters wrong.

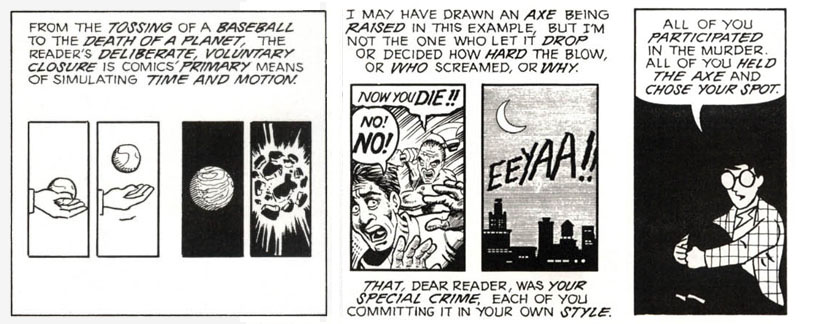

The “random” in “random encounter” refers to the fact that they’re procedurally generated. It doesn’t mean that they’re capricious or disconnected from their environment. I talk about this in greater detail in Breathing Life Into the Wandering Monster, but when you roll a random encounter you need to contextualize that content; you need to connect it to the environment.

And because the encounter is connected to the environment, it’s meaningful to the PCs: Creatures can be tracked. They can be questioned. They can be recruited. They can be deceived. The mere existence of the encounter may actually provide crucial information about what’s happening in the region.

Random encounters — particularly in exploration scenarios — are often more important as CLUES than they are as fisticuffs.

They can also be roleplaying opportunities, exposition, dramatic cruxes, and basically any other type of interesting scene you can have in a roleplaying game. As such, when you roll a random encounter, you should frame it the same you would any other scene: Understand the agenda. Create a strong bang. Fill the frame.

Once you recognize the false dilemma here, the problem basically just disappears. If the PCs have camped for the night and a group of orcs approaches and asks if they can share their campfire… do I even care what their challenge rating is?

If I roll up the same encounter and:

- The PCs subdue and enslave the orcs.

- The PCs rescue the slaves the orcs were transporting.

- The PCs discover the orcs were carrying ancient dwarven coins from the Greatfall Armories, raising the question of how they got them.

- The PCs follow the orcs’ tracks back to the Caverns of Thraka Doom.

Does it matter that the PCs steamrolled the orcs in combat?

I’m not saying that combat encounters should never be challenging. I’m just saying that mechanically challenging combat isn’t the be-all and end-all of what happens at a D&D table. And once you let go of the false need to make every encounter a mechanically challenging combat, I think you will find the result incredibly liberating in what it makes possible in your game.