Running a successful horror scenario in a roleplaying game can be a unique challenge, but it’s not the impossibility that some feel it to be.

There is one baseline requirement, though: The players have to be invested in the game world. They have to CARE about something. Their own PCs at a minimum. The whole group is better. Other stuff in the game world is ideal.

And, as a horror GM, you want to be aware of what your players actually care about: If they don’t care about something, then they cannot fear its loss. Target what the players care about, which may not be the same thing as what their characters care about.

The thin line of distinction here can often be found in joking around the table: It’s okay if the players are using jokes to try to distract themselves from the danger. That’s part of horror! It actually shows that they’re invested in the world.

But if the players are using jokes to distance themselves from the game world, that’s a problem: Those jokes de-invest the players’ engagement in the game world. It’s the difference between Buffy cracking wise with Willow and the MST3k crew mocking a movie.

The distinction between these two forms of humor at a gaming table – where roleplaying, meta-game discussion, and meta-commentary often flow around each other seamlessly – can be very subtle, but it’s important.

Long story short: If you’re trying to run a horror game and you’re having problems with disruptive behavior (i.e., players disrupting the table’s investment in the scenario), then it’s useful to step back and have a group discussion about expectations. However, it’s easy for this conversation to misdirect towards things like “no laughing” or “horror is serious business, so everyone put on their frowny faces.” In my experience, this is often ineffective and it can be more useful to drive to the heart of the matter: Why don’t you care?

Fixing that issue may be a much more complicated issue (and beyond the scope of this essay), but the frank discussion is usually a good place to start.

In any case, let’s lay this digression aside and assume that you have a group invested in their characters and the game world.

What next?

THE CORE OF HORROR

Regardless of medium, achieving true horror is a vague and unspecific art. But you’re generally looking for some combination of danger, anxiety, helplessness, and enigma.

These qualities are often associated with the lack of power, and this can lead to the assumption that horror becomes impossible if characters have a certain amount of power: You can’t do horror with superheroes. Or D&D characters. Or colonial marines in a warship armed with nuclear weapons.

In general, however, the objective amount of power you have is only relevant because it influences your RELATIVE power. And even relative power is only meaningful insofar as it affects PERCEIVED power.

If you perceive yourself to be overpowered by something that wants harm you (or, often more effectively, those things and people you care about), then you are in DANGER.

If you see no way to escape or redress the imbalance of power, you are HELPLESS.

If you are concerned that such danger or helplessness could happen, you are ANXIOUS.

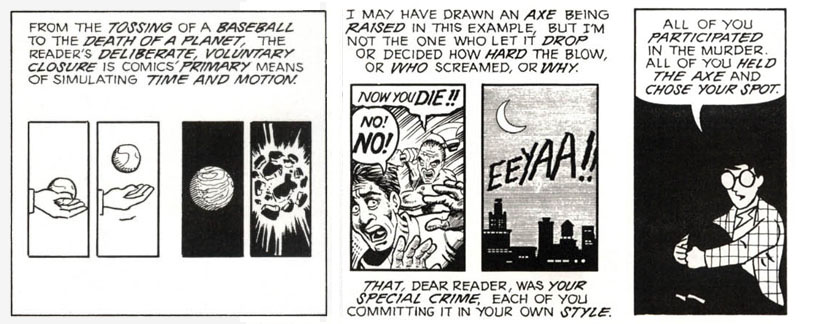

Finally, when confronted with an ENIGMA, players will perform an act of closure. With proper circumstance and priming, their closure will create the threat of danger or helplessness, either heightening the sense of anxiety or creating anxiety even in situations where it isn’t necessary.

Scott Mccloud – Understanding Comics

SHORTCUTS & MULTIPLIERS

There are a number of shortcuts and multipliers you can use to create or enhance horror.

PHOBIAS have various sources, but they are all pre-trained fear responses. They bypass rational threat assessment and immediately trigger a sense of overwhelming danger.

Making the players fear for something other than their PCs (i.e., themselves) allows you to place the endangered thing or person at a distance. This DANGER AT A DISTANCE reduces the perceived ability to do anything about the danger, thus reducing perceived power and enhancing helplessness.

Conversely you can endanger PCs from a distance or in a way they don’t understand. If they can’t figure out how to apply their power to MYSTERIOUS DANGER, they also lose perceived power. (I used this technique in The Complex of Zombies with the bloodsheen ability to create a terrifying mystery.)

You can achieve similar effects via DILEMMAS. If multiple things the PCs care about are simultaneously put in danger (preferably in different locations), being forced to choose which one to help or save can create helplessness. (Or it can force the party to split up, which is also great for horror: It reduces the perceived power of the characters and it lets you put isolated characters at risk, presenting danger at a distance for the rest of the group.)

You can use PRIMING to direct how players perform closure on the enigmas you present. (There are a lot of ways to do this. Horror movies actually do it with their soundtracks: Specific music cues or types of music or the lack of music prime the audience to literally imagine the worst possible outcomes from otherwise innocuous interactions – like opening a door – a thousand times over.)

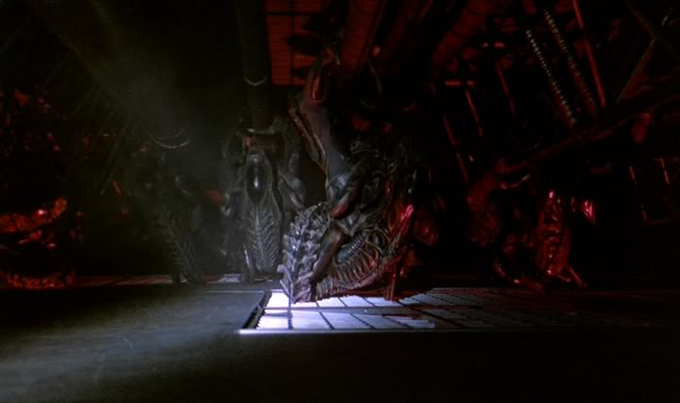

You can use the UNEXPECTED to create quick enigma, disrupt the perception of relative power, or maximize the effectiveness of a phobia. (Jump scares are a simple example, but so are xenomorphs climbing through the ceiling when you expected them to come through the doors.)

It can also be effective to ESTABLISH RUTHLESSNESS. In order for horror to exist, the threat of loss cannot simply be performative: The audience (i.e., the players) must believe the threat to be real. And the easiest way to make that happen is if the threat is real, which can be demonstrated by actually pulling the trigger (or swinging the axe, as the case may be).

This can be very effective when dealing with the problems created by genre expectations: There are all kinds of genres in which the main characters are placed in jeopardy, but are never in actual danger of being killed. This is particularly true of the pulp genres and TV procedurals that many RPGs are based on.

Modern design ethos, for example, has ingrained the belief in many groups that game play is supposed to be a predictable series of “fair” encounters. The expectation is thus that the PCs will constantly be placed in the perception of “danger,” but will never actually be at risk. You’re obviously never going to feel helpless if you know every encounter has been designed for you to triumph, nor are you going to feel anxious about the possibility of facing the next “dangerous” encounter. Horror, of course, is completely impossible under these conditions, and often the only way to break that long-held belief is to bluntly demonstrate that, no, you and/or the things you care about are NOT safe.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Let’s wrap up with a couple things you should NOT do.

First, don’t tell the players that their characters are scared. While it’s true that we have an empathetic model of mind (i.e., if we see someone smiling we often reflect that emotion and become happy ourselves because we have circuitry in our brains specifically designed to recreate the emotions seen in others) and that horror fiction – particularly film – leverages that to create fear in an audience by showing a character in fear, instructing players what their characters are feeling can often psychologically distance them from those characters and have the opposite effect.

(What you CAN do is vividly describe the emotional reaction of NPCs. Particularly NPCs that you know the players care about. The bandwidth is still limited compared to a film, but the technique can be effective.)

You should also not allow this imprecation to discourage you from using tools like sanity mechanics, assuming you’re using them correctly, of course. (Note that, when used correctly, sanity mechanics create enigma and use priming to frame player closure through foreshadowing without disrupting their emotional engagement with both their character and the moment. This is obviously not a coincidence.)

Second, never railroad the players into danger.

As the Railroading Manifesto tells us, railroading is never a good idea. But it sure can be tempting in a horror scenario! After all, if helplessness is one way of creating horror, what could make the players feel more helpless than forcing them into a preconceived outcome?

The problem is that this helplessness is not diegetic; instead of being focused on the game world (and the things that the players care about in that game world) it’s focused on you. This emotional redirection can disconnect the players from the game world, causing them to lose the investment that is foundational to the horror experience. In other words they stop caring. And often the fear you want them to be feeling is replaced with anger.

Conversely, true autonomy often heightens the horror: It’s only when choices matter that enigmas are fully engaged with (because they know the outcome of those enigmas are not predetermined; in the most simplistic form, if they could solve this puzzle faster then they might be able to save Lisa’s life). Furthermore, when players feel true responsibility for what happens (because it’s the result of the choices they made), the guilt they feel for those outcomes – and, importantly, the fear of experiencing that guilt if things go wrong – will enrich their emotional response to danger and helplessness.

That kind of emotional engagement, of course, will heighten the players’ investment in the game world, expanding the depth and breadth of the horror itself.

I think an important thing to add is what Shamus Young points out in his article about video game horror here about pulling punches: https://www.shamusyoung.com/twentysidedtale/?p=1828

While fear of death is a very powerful tool, the moment of actual death isn’t the climax of horror, but a deflation. Somebody is now out of the game and needs to roll a new character, a swerve that can quickly kill the mood at the table.

Which is also why scary movie monsters (despite technically having the ability) don’t just instantly kill everyone, because the build-up of being whittled down in resources, in trying and failing again and again to succeed against an implacable foe is much more effective than just “Snap, you’re dead.”

I know a DM who ran a horror one-shot at a convention, where presumably the players wouldn’t know each other. He also had a shill player who, about a half-hour in to the 4 hour slot, had agreed to do something that seemed slightly risky, have the character die and the player leave the game. He says the other players became significantly more nervous after one of them had to leave the game.

On establishing things the players care about, multiple conflicting binds are also very effective. Increasingly horror games are starting to hard-core it.

For example, in Delta Green you work for a secretive conspiracy of human monsters, and failing to meet their demands or avoid exposure is just as dangerous as any eldritch aberration or cultist.

Even a successful operation can put your career at risk, which impacts your personal bonds (people you care about). As @Alien@System mentioned, those often take the form of a slow build-up of reprimands and suspensions. Though it could jump strait to termination, your character is still in play as their life continues to spiral down the drain.

That’s in addition to the physical and sanity assaults, and the potential world-ending result of failure.

@Alien@System I can’t agree. I’m with Justin that in order to make a threat scary it can’t be a bluff. Now, in a horror game as opposed to linear horror media, everyone can get out alive without killing the threat, because the potential for horrible death existed in the game space.

@Justin You’ve talked about your appreciation of Ten Candles on several occasions. Why does that work for you when inevitable failure generally doesn’t? Is it the STG thing of having signed up for inevitable doom in advance?

@Avian Overlord

I find that delayed effects are sometimes helpful. The initial encounter doesn’t have to be immediately deadly, but failure starts a clock toward impending doom for that character or others. That way there are still real stakes to care about, but it preserves everyone for a subsequent buildup of tension that now directly involves them.

And a lot of horror makes use of that trope. Alien facehuggers turn chestburster. Samara Morgan calls to inform you of your seven days. Any kind of invasive body horror etc.

In any case, it’s always possible to achieve some buildup through early foreshadowing.

@ Justin

You say it’s important to establish ruthlessness, but how do you keep that from feeling like a screwjob to the player who you take out? Short of using a shill like bodhranist described, I don’t see any way of demonstrating your willingness to pull the trigger without having at least one player get blindsided by the danger levels suddenly being higher than expected.

@Aeshdan

When you say that the dangers levels are suddenly higher then expected, are you talking about genre conventions? Because that’s one thing that my players have just learned is not applicable when I run horror games. However, I don’t just go around having them die willy-nilly. The danger level is always (to some extent) signaled in the fiction. If the group enters the creepy basement, hear strange noices and decide to open the ancient chest with ominous symbols, there is a chance that one of them is going to die when the thing in the chest gets released. If the response to dying was “But it’s early in the scenario!” I would answer “Take precautions next time…” My job as a GM is to signal the danger in a fictionally appropriate way, the players decide how they want to deal with it. And that includes facing the consequences.

@Aeshdan:

One of the great things about not railroading your players is that you aren’t responsible for everything that happens in the campaign. Yes, it would be bullshit to design a scenario and say, “And this is the part where I kill Bob!” But since I don’t prep scenarios like that, it’s not something I have to waste any time thinking about.

Second, as I pointed out multiple times in the article, you want to target things the players care about: THAT IS NOT LIMITED TO THEIR CHARACTER.

Kill their horse. Burn down their house. Infect their girlfriend with an alien parasite that permanently overwrites their personality. Destroy their magic sword.

There are a lot of triggers you can pull without ever killing a PC.

It’s kind of implicit in the assumptions of the article, but because it often gets skipped over, I think it’s worth being explicit: before you get to “why don’t you care?” it’s good to first ask “do you actually want to play a horror game where you experience horror?”

Because I think it’s not uncommon for players to say “sure, I’ll play” because they want to game with their friends, and the GM wants to run a Cthulhu game, and fighting cultists and eldritch horrors instead of orcs sounds like it could be fun, and they’re fine with expecting their characters to end up crazy and/or dead.

But that doesn’t mean they’ve actually signed on for experiencing feelings of danger, helplessness, anxiety, and enigma. For actually experiencing horror, rather than just watching it at a remove.

Having been that player, more than one GM who said “hey, I’m thinking about running a Cthulhu game,” would have gotten a different answer if they’d also said “and I want you to actually feel anxious and helpless when playing this game.” I feel enough anxiety and helplessness in real life, and I game in part to get away from it…

@Anonymous Coward

Excellent point.

There is definitely a subset of players that sign up for horror games as humor games. They want to laugh at all the horrible fates that befall their characters.

I would say that Call of Cthulhu is particularly geared toward that tone, since players know just how overwhelming the Mythos is and how likely it is to encounter a fate worse than death. Their characters are either minimally in-the-know or blithely ignorant.

@7,8

What I mean is this:

“Modern design ethos, for example, has ingrained the belief in many groups that game play is supposed to be a predictable series of “fair” encounters. The expectation is thus that the PCs will constantly be placed in the perception of “danger,” but will never actually be at risk. You’re obviously never going to feel helpless if you know every encounter has been designed for you to triumph, nor are you going to feel anxious about the possibility of facing the next “dangerous” encounter. Horror, of course, is completely impossible under these conditions, and often the only way to break that long-held belief is to bluntly demonstrate that, no, you and/or the things you care about are NOT safe.”

Justin, you talk about how a lot of players are conditioned to believe that games are supposed to be a predictable sequence of “fair” encounters. So if you have a group of players who subscribe to that belief, isn’t there the risk that they will see what you are doing as a GM screwjob instead of the consequence of their own mistakes?

@9

And you can also have the characters who want to be Big Damn Heroes and go down spitting in the Devil’s eye. Again, they might want the trappings of a horror game, but they don’t want to experience horror.

Great article Justin, many good points. I also really like the guidelines from Dennis Detwiler of Delta Green on running horror, which focus on ‘lack of control’ and ‘lack of understanding’ from a player perspective. He also touches on many points you make – http://detwillerdesign.squarespace.com/blog/2013/5/29/delta-green-creepiness-a-how-to-guide

I also really like the guidelines of thinking about horror as having a certain tempo to it, with the ‘trajectory of fear’ – https://img.fireden.net/tg/image/1453/84/1453840962349.pdf