HUGIN JORHUND ATHUKAVORE THUUNLAKALAGA

(Created by Allen Voigt)

When he was young, Hugin wrangled with Jaagrik, Kaga, and Zuri, goliaths who were a little younger than him. (For a goliath, “wrangling” – which might be more accurately translated as something closer to “competing” – is the childhood word of playing.) During this time he was given the honorific of Athukavore, a goliath word which translates as “noisemaker.” But he grew apart from his playmates when he was taken under the wing of Kapanuk, one of the tribe’s Dawncallers.

Recognizing Hugin’s divine spark, Kapanuk sought to train Hugin to become a cleric of Talos, the God of Storms. Talos, however, did not seem to wish to use him as a conduit of power. Hugin hoped that things might change when he passed into adulthood, and so he gave up his “blood ball” (a mock javelin his father had made for him that was, in truth, little more than a pointy walking stick made of bone), and entered the Crawl: Passing through the tunnel, Hugin hallucinated that the wyrm which made up his home came back to life and melted the bones of his friends and family, only by plunging deep into the ice was he able to survive.

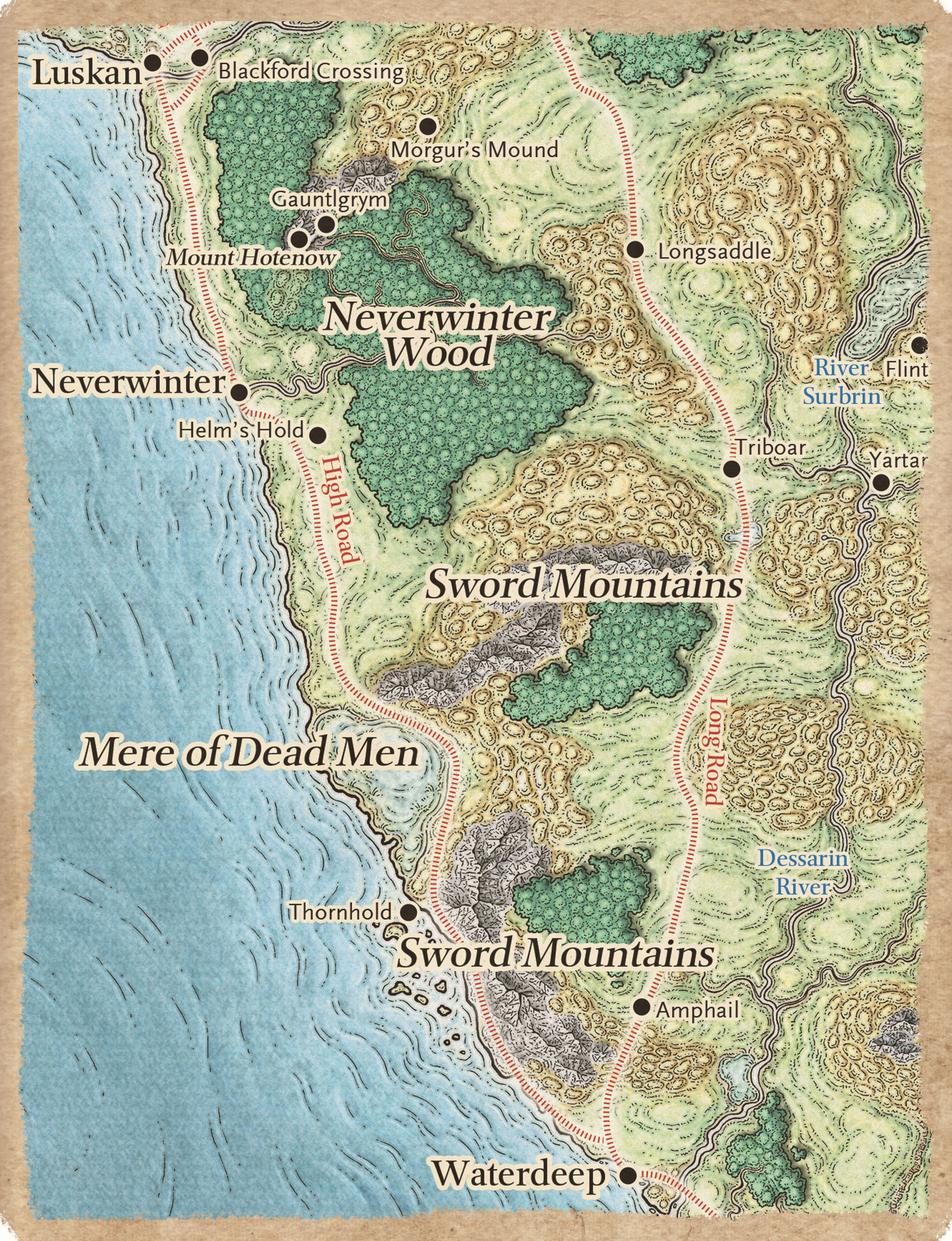

Hugin emerged from the Crawl into adulthoos. But nothing had changed. There was still no divine spark. Frustrated, Hugin took a pilgrimage to Luskan. In the City of Sails, a member of the Arcane Brotherhood named Nass Lantomir convinced him to take part in the Wet Parade at the Winter Palace.

The white-spired Winter Palace is Auril’s temple in Luskan. The structure is a roofless array of pillars and arches carved of white stone. The rituals of Auril’s worship often seem cruel to outsiders.

The Wet Parade is a ritual in which supplicants don garments packed with ice. They then journey between six white pillars known as the Kisses of Auril, which are dispersed throughout the city. The worshippers move from pillar to pillar, chanting prayers to the goddess. Upon reaching a pillar, a supplicant must climb it and then “kiss the lady,” touching lips to a rusty iron plate at the top.

These events resemble frantic footraces. In winter, there is the added risk of frostbite and injuries caused by falling from the ice-slicked pillars. The parade runners are cheered on by patrons who come out of nearby taverns to place bets on the stamina of the participants. Those who finish the race are thought to have helped make the winter easier, and they rarely have to pay for food or ale all winter long. (Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide, p. 25)

There is some similarity between Luskan’s Wet Parade and the Blesstide “parade” of Waterdeep: On Auril’s Blesstide, an informal festival held on the first day of frost, paraders dressed in white cloaks (but otherwise naked) run from Cliffwatch in the North Ward across the city, through West Gate, and then leap into the icy waters of the Sea of Swords. (City of Splendors, p. 15)

The Six Kisses each represents a different principle of Auril’s faith, while also physically combining two of Auril’s three forms (which are the Cold Crone, the Brittle Maiden (Lady Icekiss), and the Winter’s Womb (the Queen of Frozen Tears)):

- The Kiss of Ice, which is fairly self-explanatory; it is the crucible in which faith and mortal strength are tested (Maiden ascendant, with the Crone)

- The Kiss of Fire’s Quenching, which is not only the literal quenching of fire’s warmth, but also symbolically the destruction of civilization as personified in the hearth (Crone ascendant, with the Womb)

- The Kiss of the Open Door, for Auril holds that no structure should be made fast against the wild cold (Maiden ascendant, with the Womb)

- The Kiss of the North Wind, which is also known as Auril’s Breath or the Breath of Death; it is one and the same with the cold lack which is the air in a dead man’s lungs (Winter’s Womb ascendant, with the Crone)

- The Kiss of Darkness, also known as the Kiss of Isolation, for in the darkness each man stands alone, revealing the lonely truth of all sentience (Crone ascendant, with the Maiden)

- The Kiss of Eternity, for in ice that which would elsewise be lost will be forever preserved (Winter’s Womb ascendant, with the Maiden)

How much of this symbolism Hugin understood is uncertain, but as a goliath completing the challenge was an easy feat when walking among humans. Nevertheless, he still felt no flow of power from the Frostmaiden upon the completion of the ritual.

Later, however, Hugin was drunk at a local tavern. He was approached by a tiefling woman with light blue skin. At times it seemed to him as if she was rimed in ice, although it seemed hard to be certain, and if he looked at her out of the corner of his eye it seemed as if her eyes were black, empty pits. She told him that if he still sought divine recognition and the holy purpose which came with it, then a path had been laid for him. “Look for the man with the eye of ice. He will show you the way.”

Then she was gone.

But later that same evening, a man with an eye of magical ice sat down next to him and offered to buy him a drink. Then he offered him a job: He’d heard that Hugin was from Icewind Dale, “And I have need of… let’s say a bounty hunter.” It seemed that someone had published a scurrilous treatise called The Hellbent Highborn accusing several prominent patriars in Baldur’s Gate and nobles in Waterdeep of being devil worshipers. They had not been able to discover the author’s true identity, but they knew that they had fled to Icewind Dale by way of Luskan. “All we want is for this criminal to be found and for justice to be done. You understand?”

Hugin left the bar with a pouch of gold coin and immediately made arrangements to work his way back to the Dale as a caravan guard. If hunting down this criminal and seeing her brought to justice was that path to divine recognition, then he would see it done and become what he was meant to be.

DESCRIPTION

Hugin is a dark gray-skinned goliath, standing 6’10”. He’s bald, with lithoderms – coin-sized bone-and-skin growths as hard as pebbles – speckling his skin. Around his joints (at elbows, knees, collar, hips, and so forth) are chalky white calluses, and where the skin meets these protuberances there is a dark grey-blue pattern radiating radiating out.

WYRMDOOM CRAG

W1 -VALLEY. The bones of a dragon lie half-buried in the snow. Ground slopes up from the dragon to the crag’s entrance; stone stairs to the east lead up to the goat-ball court.

Chwingas. Tiny fairies known as chwingas are often seen flitting among the dragon bones. You know that one of  them is fascinated by whistling and will come capering out whenever someone is whistling a tune. Another is fascinated by their own reflection.

them is fascinated by whistling and will come capering out whenever someone is whistling a tune. Another is fascinated by their own reflection.

W2 – GOAT-BALL COURT. Fifteen crude stone pillars stand in this raised area, with bleachers carved into the rocks. (See Goat-Ball.)

W3 – WEAPONSMITH. Your clan’s weaponsmith is Wayani Highhunter. She says she learned her forge-craft from a dwarf of Mithril Hall.

W4 – THE CRAWL. Your clan’s soft-worker, Demelok Nightwalker, dyes cloth and tans leather here. The center of the cavern bulges up, revealing a passage. Through this passage young goliaths must pass in order to become full-fledged adults. They offer up a symbol of their childhood — a doll — and crawl through the tunnel. Members of their family wait for them on the other side, ready to welcome them into adulthood. While passing through the tunnel, visions force them to face their fears. If they cannot complete the journey, then they are not ready for the trials of adulthood.

W5 – MAIN HALL. This cavern has a domed roof and a well. The southern portion of the cave is about ten feet higher and the clan-fire is kept burning here. This is where the clan gathers and socializes.

W6 – PRIVATE CAVES. These private caves are home to the “honored elders” of the clan — Wayani the Weaponsmith, Demelok the Soft-Worker, Chieftain Ogolai Orcsplitter, and Bodysmith (medicine-worker) Aruk Thundercaller.

W7 – FEASTING CAVE. This is both where the food is prepared and the feasting occurs. Members of the clan who do not have a private cave sleep here. Feast-hall wrestling helps establish the pecking order in the clan.

GOLIATH CULTURAL NOTES

Food & Drink: Elk meat, goat’s milk, berries, smoked fish.

Daily Routine: At dawn each day, the chief selects Captains who are tasked with different duties (hunting, fishing, repairing broken furniture, etc.). In addition to the clan Elders, these captains then select members of the tribe round-robin style to assist in their duties. It’s not unusual for multiple teams to be selected for the same task (i.e., multiple hunting groups), in which case informal and formal competitions between them are common.

Names: Goliaths have three names. A birth name (given by their mother and father), an honorific or nickname that can change at the whim of the chieftain (usually reflecting something they did that was particularly useful to the tribe or as a punishment for something foolish or dangerous), and the clan name. (Your clan name is Thuunlakalaga.)

- Example Honorifics: Highclimber, Nighthunter, Bearkiller, Dawncaller, Fearless, Horncarver, Skywatcher, Wordpainter, Latesleeper, Wanderlost, Shytongue, Stumblefoot

Language: Gol-Kaa, which has only thirteen phonetic elements (a, e, g, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, u, th, and v). Relatively recently, the goliaths have picked up the dwarven alphabet and begun using it to transcribe their oral traditions, etc.

Art: Most goliath art is abstract, based on astronomical observations. Their portrait art is highly abstract, with the figure being portrayed more as a constellation of their achievements rather than visual representation of what they physically look like.

Goliath clans often have dawncallers – bards who act as both sentries and lorekeepers for the tribe. Goliaths, whether dawncallers or not, are great tale-tellers and have a rich oral tradition of stories, myths, legends, and songs.

Competition: Goliath culture features a lot of competition. It’s baked into daily tasks and most forms of recreation. They often keep track of their social relationship in the form of tallies or scores (“twice more and I’ll have saved you from wolves twelve times” or “this is the fourth time I’ve given you a healing potion”).

- This includes competing with themselves: Once a goliath has done something (e.g., slay a dragon) they won’t be happy unless they’ve one-upped the accomplishment (e.g., slay two dragons, or an older dragon, or a dragon with a large hoard). Their word for becoming an adult can be literally translated as “champion.” (But, of course, even a champion has to compete to keep their title.) And their word for “chieftain” would be more accurately translated as “champion of champions.”

- Goliaths also prize fair competition. Cheating is anathema and they also feel strongly that everyone should have their turn and an equal opportunity.

Sports: Wrestling, stubborn root (like king of the hill), cliff-bolting (a vertical climbing race), goat-ball.

Honored Elders: Not all of these positions can be found in every clan.

- Chieftain

- Weaponsmith

- Soft-Worker (skilled in cloths, leather, etc.)

- Bodysmith (a medicine-worker)

- Skywatcher (religious leader)

- Adjudicator (referees for the games goliaths play, but also act as judges for other disputes)

- Childsmith (responsible for raising and watching over the clan’s children, sometimes referred to as the Tent-Mother or Tent-Father)

Dawncallers: Dawncallers aren’t exactly elders. They are the “ones who walk at night” – acting as sentries or otherwise taking care of tasks that need to be completed at night. It’s an honored position, which exempts them from the daily captain-calls. The dawncallers are often seen as mysterious and enigmatic, but they share morning and evening meals with the rest of the tribe and, particularly at the evening meal, share the oral history of the tribe (which they learn and share with each other during tehri nightly vigils).

GOAT-BALL

See Icewind Dale: Goat-Ball for the full rules and customs of the game.