IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 24A: THE SQUIRE OF DAWN

June 21st, 2008

The 11th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

Tor left the Ghostly Minstrel and turned north towards the Temple District, heading towards the Outer Cathedral. In the three weeks since he had come to Ptolus, he had felt a deep frustration growing in his heart. He had left his home and his family to become a knight and follow the path of honor. But he had found little of the certainty he had hoped for traveling with these strange companions that the mage Ritharius had sent him to. They were good people – of that he was certain, although there had been times when he had doubted – but they seemed lost in a time when he desperately needed direction.

And so he was intent in seeking out Sir Kabel Dathim, the leader of the Order of the Dawn. He had seen Sir Kabel’s cold reaction to the proclamations of Rehobath and this had, for whatever reason, created some sense of trust in him.

When he arrived at the Cathedral, Tor spoke with one of the lesser priests and was led to Sir Kabel’s quarters. The priest knocked on the door, entered, and returned only moments later to usher Tor forward and shut the door behind him.

Sir Kabel’s quarters were small, but well-furnished. An inner door led to what was most likely a bedroom, and the main chamber into which Tor stepped served as both an office and a lounge of sorts. Sir Kabel was sitting at his desk, but as Tor entered he closed a thin ledger, rose, and crossed towards the couch.

“Sir Kabel.” Tor bowed deeply. “Thank you for agreeing to speak with me.”

Sir Kabel returned the bow with a nod and then sat down on the couch, motioning Tor to a nearby chair. “Sir Torland of Barund, if I remember correctly? We spoke of horses at Harvestime, did we not?”

“Yes, but I am no knight, sir.”

“Truly?” Sir Kabel raised his eyesbrows. “Yet you bear a sword at your side and you carry yourself like a warrior.”

“I am trained in the blade,” Tor said. “But I belong to no order.”

“Would you like to?”

Tor couldn’t contain the grin which erupted across his face. “That’s why I’ve come to you!”

But now Kabel’s face, which had been drawn in thought and consideration, became clouded with suspicion. “You’re in league with the Chosen of Vehthyl, aren’t you?”

Tor’s grin dropped away and he chose his next words carefully. “He has recently been my companion.”

“How recently?”

“A few weeks.”

“And what do you think of the Novarch-in-Exile?” Kabel couldn’t keep the contempt out of his voice.

“I think he’s dangerous,” Tor said plainly. “And I don’t trust him. I don’t think Dominic trusts him, either.”

“And yet he stood at Rehobath’s side.”

“He didn’t know what Rehobath was planning. None of us did.”

Kabel nodded thoughtfully. “Do you think Dominic is truly the Chosen of Vehthyl?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think he knows.” Tor shrugged. “But he bears the signs. That’s no trick.”

Kabel grunted and then stood up. He circled behind the couch and began pacing, his words coming thoughtfully. “I don’t trust Rehobath. He claims to speak with the voices of the Gods, but the Gods speak through the Church and he would raise himself against it. I serve the Church. Not him.” He turned to Tor. “I’m not sure what to make of your friend, either. I would squire you into the Order of the Dawn, but as part of that I must ask you to keep a wary eye on Dominic.”

Tor frowned. “I won’t betray my friends.”

“I’m not asking you to,” Kabel said. “Are not two of my men – men who are more loyal to Rehobath than me – already standing guard at the Ghostly Minstrel? And you can be sure that those are not the only eyes that Rehobath has on him. I am only interested in making sure that Dominic himself does not turn against the Church.”

Tor had to think deeply, but in the end he believed that what Sir Kabel said was true. Or, at least, true enough. “I can agree to that.”

“Then come with me.”

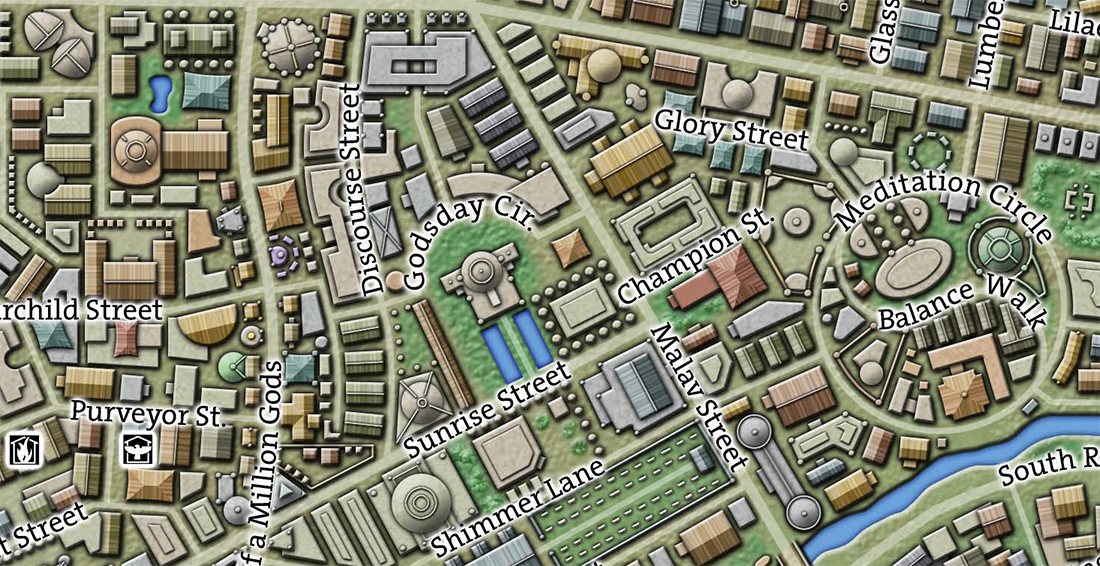

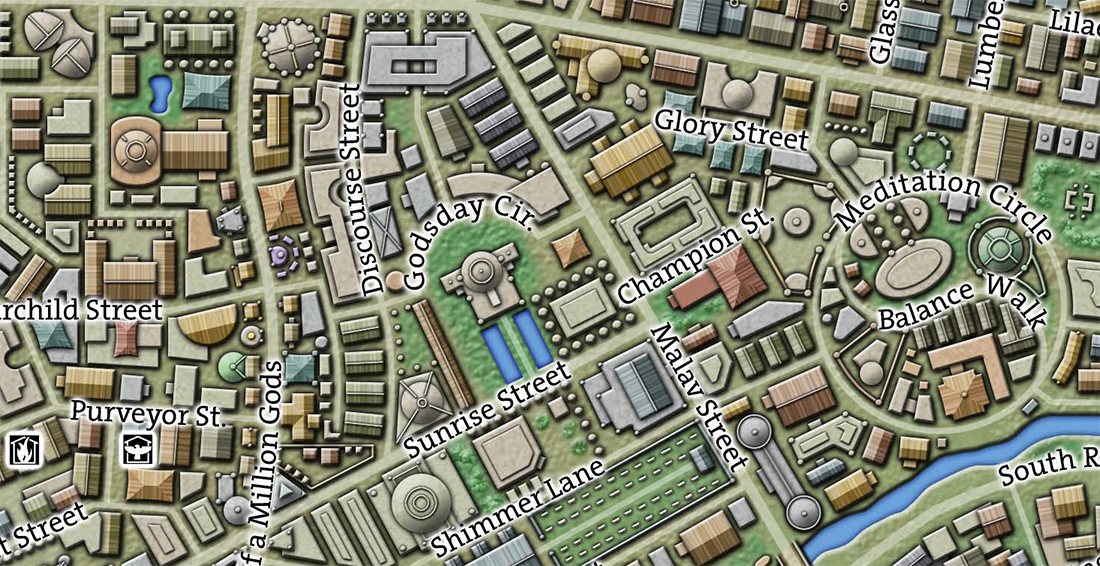

Sir Kabel led Tor out of the Cathedral and into the large complex of Church-owned buildings just to the north.

This complex was capped by the Godskeep, which housed the Order of the Dawn. At first, Tor thought he was being taken there, but instead Sir Kabel stopped in the small practice field just outside the keep’s southern gate.

A handful of knights were scattered here and there, practicing or skirmishing. Sir Kabel went over to the racks of practice weapons and pulled down two wooden swords. He tossed one of them to Tor. Tor caught it out of the air.

“I’ll rest on little ceremony here,” Kabel said. “This is your First Trial of Arms. We’ll begin with the Test of the Blade. Strike me. If you can.”

Tor attacked… and Kabel easily parried the thrust. “Good form. Controlled, yet fierce.”

Tor feinted to the left and then slashed to the right. Kabel almost completely ignored the feint and easily parried the slash, but Tor deflected his blow and plunged the point of his blade toward’s Kabel’s chest. Kabel was forced to twist his own sword in order to parry the follow-thru. “Excellent!”

Tor backed off half a pace and then quickly brought a strong blow down directly towards Kabel’s head, but Kabel was quick enough to shift his footwork, right his form, and block the blow.

“Enough!” Kabel cried, disengaging. “Now for the Test of the Shield. Defend yourself!”

Tor loosed the shield from his back and lowered himself into a defensive posture. Sir Kabel unleashed a withering flurry of attacks, and although Tor blocked many of them, Kabel’s sword seemed to constantly find the weak points in his defense.

After several exchanges, Kabel stepped back again. “I’m impressed. It’s clear you have had little formal training, but your instincts are strong and you have clearly been tested by the true heat of battle. The Order would be honored to have you serve as its squire.”

Kabel drew out a ring marked with the sigil of the Order of the Dawn and gave it to Tor.

Tor’s heart leapt. It was the dream he had sought, but scarcely hoped for. He quickly made arrangements with Sir Kabel to return once every other day for his training, and then made his way back towards the Ghostly Minstrel.

AGNARR’S ABORTED MISSION

Agnarr headed across Delver’s Square to Ebbert’s and purchased a variety of supplies, particularly a large bulk of raw meat and other food supplies. Loading all of it into his bag of holding, he set out for Greyson House: His intention was to travel down to the caverns of the Clan of the Torn Ear, gift them with the food supplies, and then practice sparring with them. The fact that he spoke none of their tongue dissuaded him not at all.

Once he made his way into the tunnels beneath Greyson House, however, he found them unexpectedly disturbed: The pit of chaos had been covered over with a thick layer of stone… albeit a layer of stone which now seemed to be slowly bubbling and boiling away as a result of the powerful forces of primal chaos trapped beneath it.

Agnarr doused his flaming sword and proceeded carefully down the hallway. As he approached the complex where the bloodwights had nested, he heard many voices and the muffled sounds of some activity.

Toying with the idea of brazenly entering the complex and confronting the intruders, Agnarr instead decided for prudence. He retreated silently back to Greyson House and returned to the Ghostly Minstrel.

NEXT:

Running the Campaign: Player-Facing Mechanics – Campaign Journal: Session 24B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index