Ten years ago I wrote Xandering the Dungeon, a detailed look at the differences between linear and non-linear dungeons. In this essay I briefly used what I dubbed Melan diagrams — a technique created in 2006 by Melan for a thread on ENWorld where he discussed “map flow and old school game design.”

These diagrams are, unfortunately, not immediately intuitive to everyone looking at them, and because I used the diagrams in Xandering the Dungeon, I’m frequently asked how they’re supposed to “work.” In fact, I’ve been asked that question three different times in the last week… which brings us to today’s post.

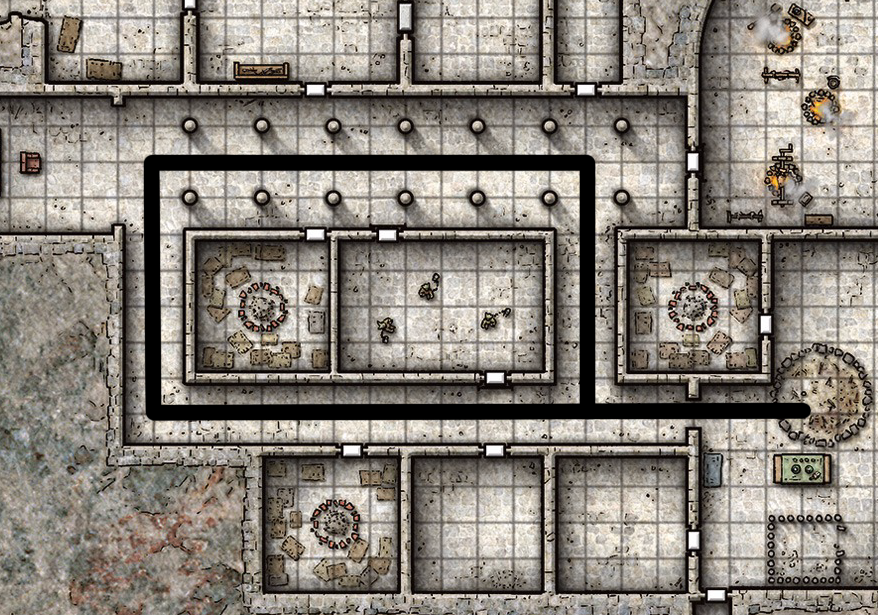

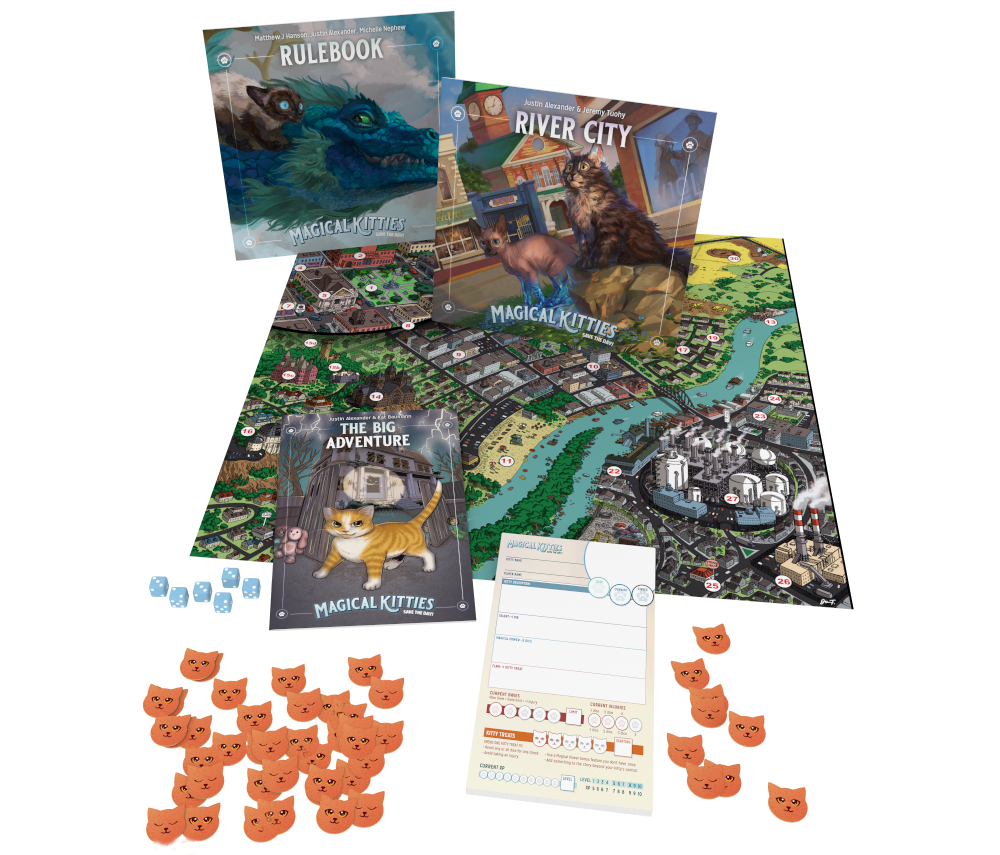

You can see an example of what a Melan diagram looks like at the top of this post. It depicts the first level of The Sunless Citadel, designed by Bruce Cordell with original cartography by Todd Gamble. (Today, though, I’ll be using Mike Schley’s version of the map from Tales From the Yawning Portal.)

So… what’s the point of this thing? Well, as Melan said in his original post:

[They are] a graphical method which “distills” the dungeon into a kind of decision tree or flowchart by stripping away “noise.” On the resulting image, meandering corridors and even smaller room complexes are turned into straight lines. Although the image doesn’t create an “accurate” representation of the dungeon map, and is by no means a “scientific” depiction, it demonstrates what kind of [navigational] decisions the players can make while moving through the dungeon.

By getting rid of the “noise” you can boil a dungeon down to its essential structure. They also allow you to compare the structures of different dungeons at a glance.

It’s fairly important to note that you don’t actually use Melan diagrams for designing dungeons. They are an analytical tool, not a design tool: You use them to look at something which has already been created, not to create it in the first place.

But if you’re looking at a diagram what does it actually mean? How is the noise being stripped out and what does that tell you? How are you supposed to interpret the diagram? Or make one for yourself?

STRAIGHTEN THE LINE

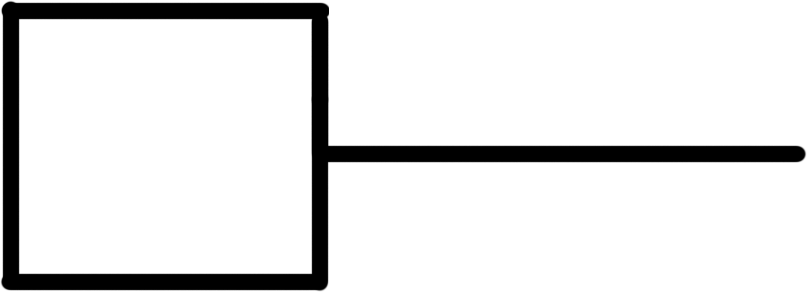

The first principle of making a Melan diagram is to eliminate all the irrelevant twists-and-turns on the map. For example, consider this path through the Sunless Citadel:

It looks really interesting, right? All kinds of turns. You went through multiple doors. You even reversed direction a couple of times!

But as far as the Melan diagram is concerned, this is a straight line: Following a corridor when it makes a turn isn’t a meaningful navigational choice. Same thing for going through a door if there’s no other exit from the room.

FORK THE PATH

“But wait a minute!” you say. “In following this path the PCs did make choices! For example, in that first circular room the PCs had the choice of two different doors!”

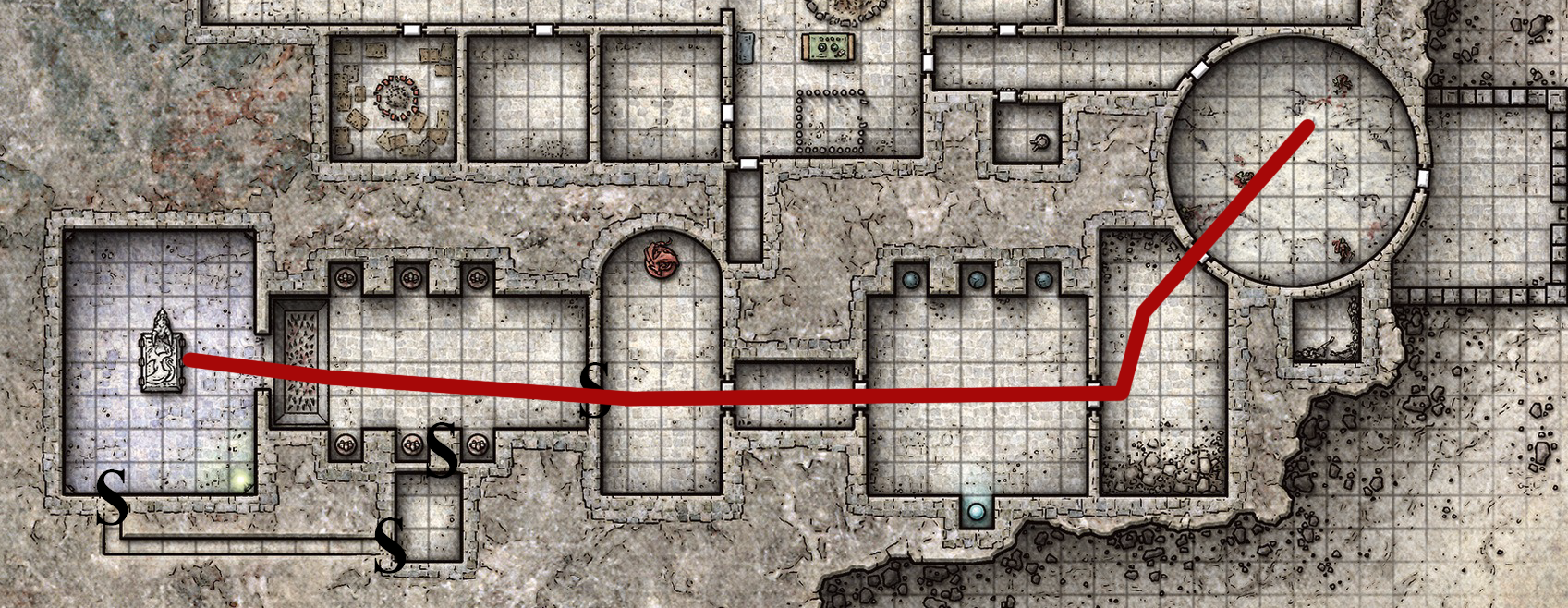

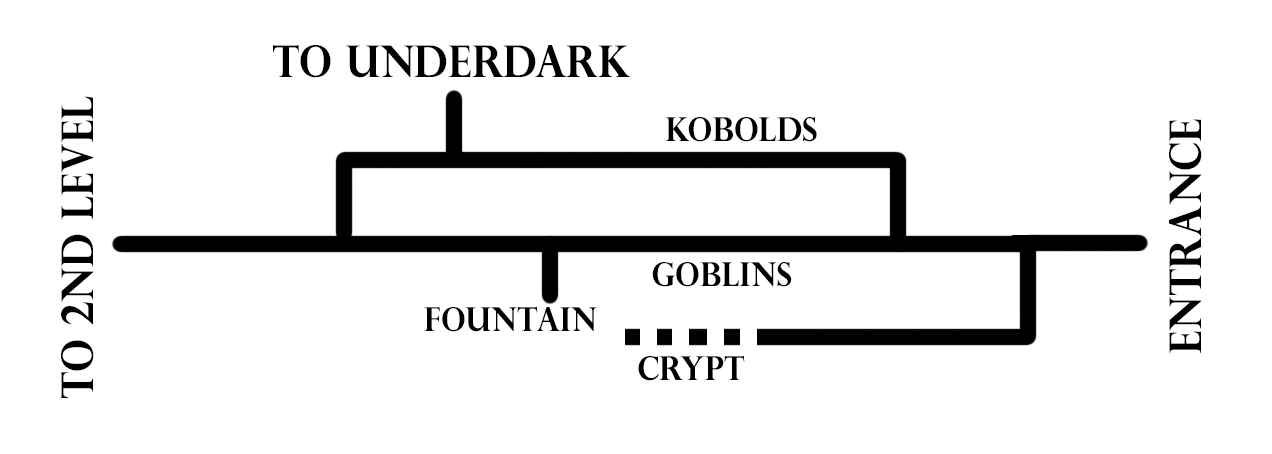

You’re absolutely right! This is exactly what a Melan diagram is interested in looking at. On this little chunk of the Sunless Citadel, there are two forking paths:

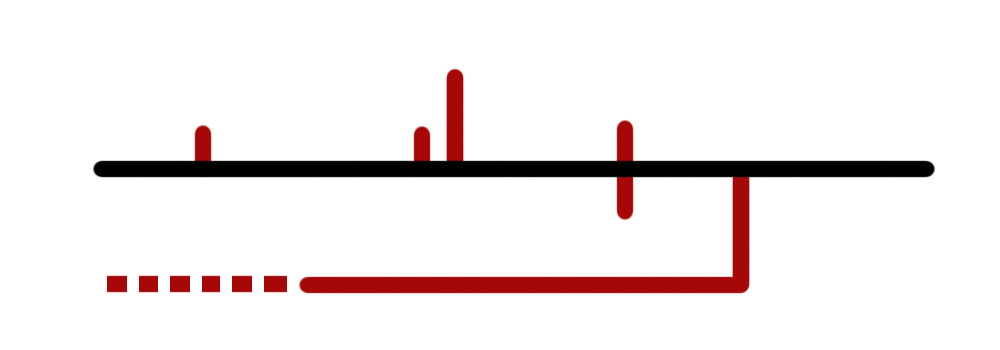

And so, on a Melan diagram, this section would look like this:

The black path is depicted as a straight line and the alternate paths are shown in red. (Melan diagrams typically aren’t color-coded like this since all paths are equally valid. We’re using the colors here for clarity.)

The length of each branch of the diagram, it should be noted, is roughly proportional to its length in the dungeon. (I don’t carefully measure this or anything, but you could if you wanted to.) In this case I’m showing them proportional per the section of map we’re looking at. (As we’ll see in a moment, these particular spurs are actually much longer.)

ELIMINATE SIDE CHAMBERS

“Wait another minute!” you cry. “I can see other doors that you’re ignoring!”

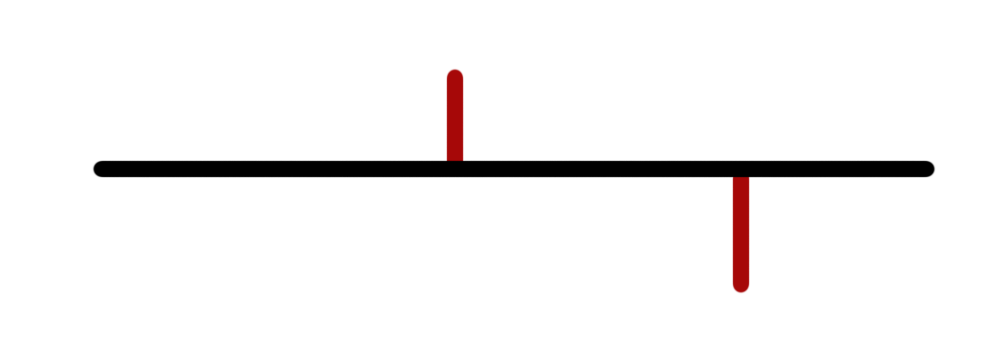

The second principle of a Melan diagram is that we are going to eliminate all paths that are only one chamber deep.

So we could take this chunk of dungeon:

And draw a diagram like this:

But the reason we don’t do this is because such a diagram becomes meaninglessly noisy. Furthermore, these side chambers largely don’t represent meaningful navigational choices on the macro-level of the entire dungeon: You might choose to bypass such doors, but if you open one of them the only “choice” is to go back to the path you were already following.

Note that you can actually see this when looking at the diagram: It’s immediately apparent that all those little spurs don’t really “go” anywhere.

(You can argue that the same thing is technically true of longer sidetracks, but in practice these longer paths tend to be more meaningful to the overall structure of a dungeon and the experience of playing it. With that being said, there’s nothing magically relevant about one room vs. two rooms and in larger dungeons you may find different thresholds for what constitutes a “meaningful sidetrack” to be useful.)

You’ll similarly want to eliminate very short dead end hallways if they exist.

DIAGRAMMATIC TURNS

“Hey! What’s with that turn in your diagram? I thought you said we weren’t mapping that sort of thing!”

That’s true. In practice, however, Melan diagrams will introduce superfluous ninety-degree turns in order to keep the diagrams relatively compact or to conveniently make room for other paths.

So if you see a turn on a Melan diagram that doesn’t have a second path branching from it, you’ll know that it’s purely cosmetic. It doesn’t actually reflect a “turn” in the dungeon; and, although the turn in our current example sort of resembles a turn in the dungeon itself, such turns on the diagram may be present even when there are no turns in the corresponding dungeon tunnel.

ELIMINATE FAKE LOOPS

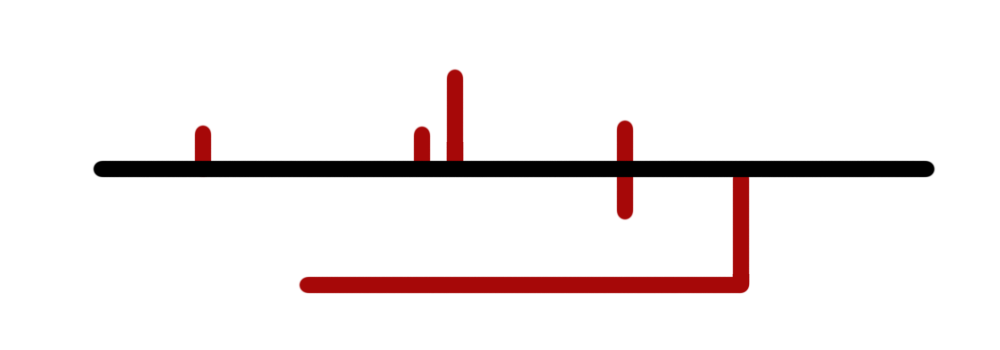

Dungeon paths will, of course, form loops. In fact, a well-designed, xandered dungeon will probably feature LOTS of loops. Ignoring routes that branch off from the loop for the moment, here’s one from the Sunless Citadel:

On the Melan diagram, it would look like this:

But what about this loop?

Well, on a Melan diagram this would actually be depicted as a straight line. To understand why, let’s start by eliminating the side chambers:

Viewed like this, you can clearly see that this is not a true navigational loop: It’s a fake fork. The navigational “choice” is a false one. After eliminating the side chambers, both paths lead immediately to the exact same place.

SECRET PATHS

When a path like this one goes through a secret door, this is indicated with a dotted line on the Melan diagram:

(Note that the other secret doors are not represented here because they lead to side chambers, which are eliminated regardless.)

An area is ONLY depicted as secret on the Melan diagram if the ONLY way of reaching that area is secret. However, even a secret door that leads directly from one “public” area to another would still be shown on the diagram as a short dotted line. (The secret path exists and is significant, even if the “length” of the path is only the width of the secret door itself, so to speak.)

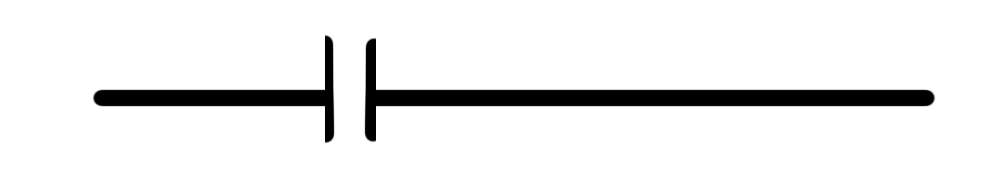

LEVEL CONNECTIONS

The last functional element of a Melan diagram are the connections between levels. When a path goes from one level of the dungeon to another (by stair, elevator, sloping ramp, teleporter, or whatever), this is indicated by a break in the line with terminating lines on either side:

OTHER ELEMENTS

Melan diagrams may also include labels (e.g., “Goblins” or “Secret Lab” or “Teleportation Trap”). These are technically non-functional parts of the diagram, but can be useful to help readers orient themselves.

Some Melan diagrams of long, linear dungeons will be split into multiple columns, with the connection between the columns being indicated by a dotted line with an arrow. (This is sometimes confused for a secret door, but it’s really just a tool for keeping the diagram relatively compact.)

CONCLUSION

If you’re reading this and still scratching your head over what the point of any of this stuff is supposed to be or what relevance the elements depicted by a Melan diagram are supposed to have, I’m going to do a full loop here and refer you back to Xandering the Dungeon, which is designed as an introduction to the sort of basic dungeon design techniques that the diagrams are designed to demonstrate.