Tagline: The Accursed Tower is a fairly solid module, with a handful of potential problems.

R.A. Salvatore is best known for his novels dealing with the drow character Drizzt Do’Urden – one of the finest swordsman in all of literature. There are some who worship these stories; others who revile them. Personally, I find them to be possessed of both significant strengths (such as Salvatore’s outstanding description of fight scenes and some of the soul-searching for Drizzt found in the Dark Elf Trilogy) and significant weaknesses (such as the repetition of some of the plots and several weak characteristics to Salvatore’s writing).

R.A. Salvatore is best known for his novels dealing with the drow character Drizzt Do’Urden – one of the finest swordsman in all of literature. There are some who worship these stories; others who revile them. Personally, I find them to be possessed of both significant strengths (such as Salvatore’s outstanding description of fight scenes and some of the soul-searching for Drizzt found in the Dark Elf Trilogy) and significant weaknesses (such as the repetition of some of the plots and several weak characteristics to Salvatore’s writing).

Similarly these novels are set in the Forgotten Realms, a campaign setting which some worship and others revile. As with Salvatore himself, I find the Realms to be possessed of both significant strengths (breadth of the setting, the wealth of detail and support) and significant weaknesses (some ridiculously bad supplements, over saturation, and general silliness).

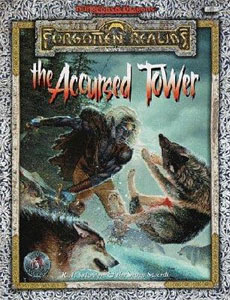

I therefore approached The Accursed Tower (an adventure for 4-8 characters of level 1-3) with a fairly open mind – Salvatore and his original gaming group (the Seven Swords) “return to the Savage Frontier” of the Ten-Towns in the Icewind Dale. The characters get a chance to explore a well known area of the Realms, while running into some well known characters of the Realms.

THE PLOT

The PCs are in Luskan, the City of Sails, along the Sword Coast (with that (in)famous “it’s up to the DM to determine how” that seems to be present in every D&D adventure I’ve ever read). They sign up to guard a merchant caravan which is going to the Icewind Dales. When they get there the caravan owner reveals that he has an opportunity for them to earn a great deal more money if they help him out with something.

It turns out that the caravan dealer is searching for a ruined tower where a mage died while researching a healing salve with the potential to help a great many people. If the PCs help him get the notes from that research, they will not only be helping in his humanitarian quest – but will also share in a significant portion of any recovered treasure.

The PCs track down the location of the tower with the help of a few familiar faces – Regis and Drizzt from Salvatore’s books – and then go off to obtain the diary. They do so. End of story.

Except, that’s not all that’s going on. The caravan driver isn’t actually a humanitarian — he’s an evil mage who has killed the actual caravan driver and taken his place. The research he’s after isn’t for any healing salve – it’s for becoming an immortal lich.

It’s time to insert the dramatic music.

THE GOOD STUFF

The set-up is intriguing and provides a solid base for the adventure. Salvatore and his gaming group construct a complex plot with several different hidden agendas and machinations going on behind the scenes – wheels within wheels is the order of the day. First, you’ve got the dual nature of the NPC who hires the PCs. Plus, one of the people the PCs get to help them out is actually an ancient barbarian sorceror, who once fought against the evil mage who owned the Accursed Tower and was responsible for his downfall.

The adventure is also blessed with some remarkably strong NPCs. Drizzt and Regis, of course, get an extra boost thanks to their literary background, but there are several others – including the father-son team from the caravan who befriend the PCs, the barbarian sorceror, and several others.

I was also impressed with a number of hooks which were left open for future expansion at the DM’s discretion – such as a scroll the PCs find half-buried in a snowdrift, with no ready explanation as to how it got there or why.

Finally, the entire package is strong one. As per usual for a TSR book the production values are high, the art is of decent quality, the book has been thoroughly proofread, and the lay-out is clear.

THE BAD STUFF

First, there’s no excuse for recycled art in a 32 page book – even if you are just filling up the quarter page of blank space left on that second-to-last page. This is particularly true if you’re TSR. They’ve published hundreds of books. Surely there was a piece of art from some other book they could have recycled instead of copying the art from page 17.

Second, the book suffers from that perennial Realms problem: Silly names. Maybe some people don’t have problems with names like “Peddywinkle” in their fantasy campaigns, but I do.

Third, random encounters are not a substitute for meaningful plotting. Although the first part of this adventure deals with a caravan trip, absolutely nothing happens on that caravan trip of any significance. The only planned event is a goblin encampment, and that only happens if the PCs follow a specific set of tracks. Everything else is a random encounter. I wasn’t too impressed with this – you could just as easily have said “the PCs are in the Icewind Dales” instead of “the PCs are in Luskan”.

Fourth, the “healing salve” cover for the archmage’s true intentions was a little annoying. It is described as “healing any wound and curing any disease”, and the guy goes on to say how he wants to “make this salve known to all, so that the world would be free of sickness”. Yeah, right. Did the Realms suddenly become devoid of healing potions?

Fifth, the map on the inside front cover is of the caravan route. Along this route are numbers. What these numbers are supposed to be is never mentioned, but you can interpolate and figure out that these represent how far the caravan gets on each day of the journey. This has relatively little importance (after all, it is a set path), especially considering the complete unimportance of the caravan drive to the overall adventure in general. The book would have been better served with a map of the Icewind Dales, where the PCs have to trek all over the place to figure out the location of the tower.

Finally, the early part of the adventure is fairly railroaded (except for those sections where nothing of importance is happening). The last part of the adventure, where the PCs have reached the tower, is nothing more than a standard event-by-location dungeon.

CONCLUSION

The primary appeal to The Accursed Tower is going to be for those familiar with Salvatore’s writing. The basic plot and elements of the adventure are nothing to get excited about (and are, in fact, possessed of several drawbacks) – but this can be mitigated when the PCs run into characters well known to them from their favorite books. It’s the same kind of rush you got from the line, “Anakin Skywalker… meet Obi-Wan Kenobi.” Or from those Howard stories where you’re following some unfamiliar character and suddenly they run into Conan.

So, The Accursed Tower gets an average rating overall. Those with an interest in Salvatore’s writing might want to pick it up; those with an undying hatred of Salvatore, Drizzt, or the Realms should avoid it at all costs.

Style: 3

Substance: 3

Author: R.A. Salvatore and the Seven Swords (Mike Leger, Brian Newton, Tom Parker, David Salvatore, Gary Salvatore, and Jim Underdown)

Company/Publisher: Corsair Publishing, LLC and Sovereign Press, Inc.

Cost: $25.00

Page Count: 168

ISBN: 0-9658422-3-1

Originally Posted: 1999/08/16

I honestly have no idea what my problem with the name “Peddywinkle” was.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

@ Justin,

Re: Disliking the silliness of a campaign with town names like “Peddywinkle,” I’d agree with your original impression that it detracts from the gaming experience. It would interfere with credibility of the realism, in my opinion.

I think your comment that the art was decent, looks accurate, at least for the cover. You’re also right that TSR shouldn’t have recycled illustrations from one part of an adventure module to another part of the very same module. That strikes me as being poor editing, and just a sloppy cheat.

Since this is an analysis of the quality of writing in producing an adventure, and looking you up online, you’ve produced more than your share of supplements… here’s a question. If as you mentioned, that so many people revile this Salvatore character’s writing, and you observe it’s got several “weak characteristics,” why aren’t adventure writers consistently top-notch?

I’ve read someplace that Table-top RPG writers are among the lowest paid in any writing industry. One article mentioned that science fiction authors were paid 5 cents a word, and RPG authors got only 3 cents a word. Can that even be accurate? I’m not sure what magazine article writers, or newspaper columnists get, so I have no way to judge if that 3 cents number sounds right. Not sure how many words are on a page at 3 cents, either?

If 3 cents is accurate, it still begs the question, aren’t there enough starving college students in English Lit. classes that love gaming, who’d jump at the chance to participate, “make a name” for themselves, and write consistently well?

Maybe your background in acting and authorship, would add some insights into how the various entertainment/publishing industries work. It’s a mystery to me why there isn’t more rigorous consistency of quality written work in a market of paying buyers. Surely, some of the products must be targeted towards a more discerning adult market, beyond the 13-16 year olds WotC seems marketed to. The people reading the critics comments would be a good group to target, since they will withhold their cash, based on a bad review from a trusted reviewer, as often as not. Or, is there more than meets the eye on that count, too?

I’d be interested in any insights you have to offer on the market forces, or others at work in this area.

5 cents/word makes something a Pro-paying market in the world of short stories. 3 cents/word is the semi-pro rate. It seems entirely reasonable that game writers would be payed, on average, somewhere around 3¢/word.

Pagan Publishing (who publish some of the nicer Call of Cthulhu products) pay 4¢/word according to their website, and it wouldn’t be that surprising if they are on the higher end.

@ J. Forbes,

Wow. And from what you’re saying, 4 cents is higher end pay. To quote from John Belushi in the movie, Animal House, upon learning he’s being expelled for misbehavior: “Seven years of college, down the drain…”

How many words do they consider constitutes a “Page,” then? Maybe games that use double columns have fewer words per page? Not sure how many words in either case. Any ideas?

I was curious, and looked at some old RPG books, and found some with readable fonts, that had double column formats. Maybe these are bigger than is normal, and a more typical page would have more words?

This is what I came up with: About 9-10 words a line, 60 lines per column, 2 columns. That seems to average about 10 words x 60 lines x 2 columns = 1,200 words a page. If that is indeed typical for a page count. Maybe the font was bigger than normal, or normal pages aren’t double columned format?

Assuming that word count is correct, (1,200 words/page), then you’d have the following price ranges paid depending on word/price:

3 cents/word = ( .03 x 1,200 –> $36/Page)

4 cents/word = ( .04 x 1,200 –> $48/Page) $60/Page) <– Doesn't Exist on this Planet ?

@ Justin,

Are any of these ideas remotely correct? What about rpg artists per page, any rules of thumb?

Damn, it deleted what I typed.

The previous post should have said:

3 cents/word = ( .03 x 1,200 -> $36/Page)

4 cents/word = ( .04 x 1,200 -> $48/Page) $60/Page) <- Doesn't Exist on this Planet

@ Justin,

Are any of these ideas remotely correct? What about rpg artists per page of art, any rules of thumb?

How long does it take to write an average page in an adventure?

Thanks for any insights into how any of this industry works.

WordPress did it TWICE! It’s deleting portions of what I’m typing into the box.

For the 4 cents a word, I wrote that it was the Pagan Printing Rate. It added on the rate for 5 cents/word, but deleted any mention of the math for 5 cents/word. TWICE. Arrr.

5 cents/word = ( .05 x 1,200 –> $60/Page) <– Doesn't exist on this Planet

So I just checked a few other websites and Miskatonic River Press, who are also a reputable publisher of good quality scenarios, pay 2¢/word.

So I’d guess the answer to why more people don’t write them is that

A) It’s hard

B) It pays poorly

Re: Science fiction authors getting paid 5 cents a word. It should be noted that this is specifically for short stories published in magazines or (most) anthologies, but I believe that’s accurate. This used to represent decent pay (back in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s), but the rates never went up with inflation. Why? Well, largely because the SF short fiction market is the last surviving vestige of the pulp magazine market. And a lot of emphasis needs to be placed on the word “vestige”.

(By contrast, a beginning midlist novelist is often paid an advance of two or three times that amount from a Big 6 publisher.)

Re: Tabletop freelance rates. A decade ago when I was an active freelancer in the RPG industry, 3 cents was the typical rate I was earning. AFAICT, this hasn’t shifted much (and may have even declined on average).

“Aren’t there enough starving college students … who’d jump at the chance to participate?” Yup. Which is one of the reasons why people only get paid 3 cents per word: The supply for freelance RPG writers is so ridiculously high that publishers don’t need to pay much in order to find people to work for them.

The other reason is that there just isn’t that much money in the RPG industry: Any rate being paid to the writer ultimately comes from the money being earned from selling the book they wrote. An RPG product selling 1,000 copies is now considered a success. Sell it for $30, of which the publisher will see $12 if they’re lucky. So call it $12,000 in revenue.

If that’s a 200 page book at 1000 words per page, that’s a 200,000 word project. At 3 cents per word the writer would get paid $6,000… which is half of the publisher’s revenue for the project. And they still haven’t paid the artists or the printer.

Re: Artist rates. I don’t have enough direct experience to really tell you anything definitive. My experience with L&L suggests that the rates for artists I wouldn’t be ashamed to have in my project are all over the place. (Probably in large part because “decent artist” is a category which overlaps heavily with “artist who’s getting work outside the RPG industry”.) I would frequently encounter artists with what seemed to be roughly the same quality of work and background, but one would be charging 5x what the other one was.

@ Justin,

That’s solid information, thank you.

You mention that 1,000 copies is a good number to sell of an RPG product. I’ve read that, too. How can it be worthwhile to sell $30 books/supplements, when the publisher maybe gets $12 on that, before factoring in artist costs? What kinds of sales would you need to make that commercially viable? Seems like lots of risk, then little gain, then taxes, then rip-off artists that sue you for not paying them for the art work they flaked out on actually doing for you…

Maybe it becomes more of a commercial venture for a publisher, if you are doing everything via PDFs, and only send physical copies using print-on-demand?

Not sure if that works for multicolor covers, or if it requires preprinting batches of them by the 100s. I think that used to require batches of 1,000 or 5,000 for the printers to even consider it, but I’m not expert on the subject.

Off that subject, if a response to a post doesn’t print what you typed out, is there any way to retract it and rewrite it?

Justin,

Gaming by encounter tables and events by location (keyed dungeon maps), was the style of adventure design in its heyday, and there was a reason that it worked. A well-designed adventure with a coherent story has no value in replaying it, while a wilderness dominated by encounter tables, can be played over and over again. The adventure objective, a quest for a healing potion and a bad guy who killed and posed as a caravan leader was influenced by a 1960’s Adventures of Sinbad movie, that was a whole lot more imaginative than most of the modern role-play adventure writing. Also, the goals have to be kept simple for the young minds that played D&D at the time.

A little known fact about the WW2 armor (tanks). Those things were at a premium. Tank gets destroyed the crew cooked alive inside or killed by the splinters of metal bouncing all over the inside. Unless the ammunition itself exploded inside and damaged all beyond repair, the tank is REUSABLE – tow the wreck to the repair factory, lift off the armor, hose out the insides to get out the blood and the bits of flesh and gore. Repair the equipment, put the armor back on, and send in another crew. End of story. Worst come to worst, put together a working tank from several wrecks. Even burned out, the armor shell can be cleaned off and reuse. Anti-tank ammunition designers started taking this into account and designing the kinds of payload that would damage the tank more, so as to make it beyond repair – one target was for the ammunition to destroy the measuring gauges and optics – how hot the engine is, periscopes etc…

D&D players have a tendency to replay the adventure modules over and over again. They will use the same map, but tailored to their own unique story that makes up the game. This makes sense, since the D&D module is really a pre-packaged setting, and the stated adventure goal, to recover the potion in a tower, is incidental to that setting. That caravan will set off time and time again for a variety of different purposes, fit to the individual needs of the various game groups. The give-away is the admonition that it is the DM’s own responsibility to account how the party ends up at the starting point.

@ Brooser Bear,

Your observation about the 1960s Adventures of Sinbad movie being the partial inspiration for this Drizzt “The Accursed Tower” module is a hoot. Finding the antecedents of inspiration or game design is always fascinating detective work, and often humorous.

*”Gaming by encounter tables and events by location (keyed dungeon maps), was the style of adventure design in its heyday, and there was a reason that it worked. A well-designed adventure with a coherent story has no value in replaying it, while a wilderness dominated by encounter tables, can be played over and over again.”*

I’ve been reacquainting myself with the gaming industry for a while, and some of the things that come up are surprising revelations. It seems that recycling is a good idea in general, and re-using modules with keys and encounter tables, strikes me as something that shouldn’t have a shelf life, but always a tool for the referee to rely on. What was supposed to supplant this? Some kind of pseudo-activism by Ron Edwards and co, where everything is narrativist? Some of those games may indeed be fun, but, for myself, they’d always be taken in moderation and not in any way seen as a ‘next-step’ evolutionary replacement for older styles of hexcrawls, mysteries in need of solution, and dungeons of some kind.

It was particularly offensive that that Forge group tried to equate “Fantasy Heartbreakers,” (newly authored game systems that didn’t incorporate Ron Edward’s narrativist ideas) as being somehow, obsolete and archaic, because they’d missed the boat on necessary changes in the gaming industry. As if game-systems not using narrativism were innately inferior and passe. As if. Well, he had his 15 minutes of profitability through slander.

Not saying some narrativism can’t work, you may have some method of incorporating it into your campaigns. If it was juste aspect of the over all old-school play, it might be quite all right. Gygax, himself, had no personal respect for role-playing as such, and in this case, I’ll tentatively agree with him. You turned me on to an article about one of Gygax’s last interviews, in May 2005, I think, with Paul La Farge. Here’s La Farge describing a play session with Gygax and the man’s perspective on the ‘role’ in role-playing, as he understood it:

*”…on a module he wrote for a tournament in 1975. This was before the Tolkien estate threatened to sue TSR, and halflings were still called hobbits. So I got to play a hobbit thief and a magic-user and Wayne played a cleric and a fighter, and for four and a half hours we struggled through a wilderness adventure in a looking-glass world of carnivorous plants, invisible terrain, breathable water, and so on. All of which Gygax presented with a minimum of fuss. The author of Dungeons & Dragons doesn’t much care for role-playing: “If I want to do that,” he said, “I’ll join an amateur theater group.” In fact, D&D, as DM’ed by E. Gary Gygax, is not unlike a miniatures combat game. We spent a lot of time just moving around, looking for the fabled Teeth of Barkash-Nour, which were supposed to lie in a direction indicated by the “tail of the Great Bear’s pointing.”*

Interesting stuff.

Here’s a link to that above article if anyone would like to check out the interview with Gygax:

http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.believermag.com%2Fissues%2F200609%2F%3Fread%3Darticle_lafarge&date=2008-10-04

Neal,

Who is Ron Edwards, what was the Forge, and what did his narrativist ideas consist of? Was he the force behind the linear plot setting like Dragonlance, and why did TSR switch to linear adventure structure?

@ Brooser Bear,

Ron Edwards and “The Forge” all happened after my time, and are mostly defunct, now. Ron Edwards wrote a game called Sorcerer, that I’ve never played. It won the Diana Jones Award, for being, in their opinion, most innovative game of year, 2002.

The Forge was a website, formerly Hephaestus’ Forge. They abbreviated the name down to just “The Forge” and their logo shows an anvil with sparks. There may some details that aren’t perfectly accurate, but this is my take on that movement, in a nutshell. The Forge, was a hotbed of rabid fanboys being led by their demagogue, Ron Edwards, and his close associates. People that contended with their interpretations were abused on the site and shouted down, as a matter of course. Lots of heat, certitudes, dogmatic cant, and a hermetic imperviousness to insight. Edward’s pose was that he was bringing about a sort of revolution in gaming, by introducing Game Theory. Maybe others had done some work in that direction before, Justin will correct me on any errors, but these guys turned it into a malicious cult for profit. Many of these definitions were always vague and endlessly discussed, which sickened a lot of people. Rightly so.

They went on and on about GNS Theory (Gamist/Narrativist/Simulationist), and a previous theory (the three fold model) (GDS?), it got later updated to being called Creative Agenda (CA), as part of Components of Exploration, but most especially System. I have no idea what that means.

In these ‘theories,’ they debated which aspects of gaming were most important to rewarding and meaningful play. Previously, someone other than these persons, had defined Simulationist games as superior, and Ron Edwards and co. didn’t like that style of play (think GURPS, and other insanely overdetailed fiddly game systems). Edwards preferred Narrativist … think: Storyteller System/ Storytelling System, kinds of game systems. Gamist, is more of a style where realism is limited, as the game is based on following rule sets that may be arbitrary… D&D might be that style, I’m not sure. Ron Edwards set out to redefine the three competing styles (in his mind) with Narrativism at the top of the hierarchy, and other styles as not fit for creative adults to play.

Here’s his site with some articles on what they were all about:

http://www.indie-rpgs.com/articles/

I read about all of this after the fact. Ron Edwards shut down the site in 2010, when his popularity massively waned from overexposure, then purged lots of its material, and left only the articles he wished to keep for posterity, claiming that he’d achieved everything he set out to do (influencing the gaming market). Mostly, people began to get tired of his attempts to control the industry, and maybe began to see through him.

Before I knew who he was, or what the issues were, I was struck by the tone of college-campus pseudo-Marxian cant in the terminology these guys devised. They came up with a whole lexicon. They seemed to be implying that anyone that didn’t embrace their ideology (and it was one, albeit, one that steered money from competitors in the gaming markets towards themselves) was some kind of oppressor of poor helpless players. If you were old-school and had a GM, that smacked of class-oppression, or sexism, racism, you name it. They had GMs for some games, but it was always tainted with suspicion. Basically, they set up their business competitors in the gaming markets, and people that played other styles of game, as socially unacceptable demons, and then target them for group ostracism and aggression. Incidentally, your flock, seeking certitudes and you provide them, buys your products as a secondary benefit. Basically, an updated Politically Correct form of Elmer Gantryism. Or some of the corrupt televangelisms. If you don’t attend their spinster church on Sundays, you’re going to hell.

They probably did inspire some independent ideas in gaming like players taking turns to be GM, or everyone contributing one aspect at a time of a world. It may have been someone else, though. Some of this stuff, like Ben Robbin’s indie game, “Microscope,” is interesting stuff, however. But, the Forge’s angry rant was that old school was somehow oppression and behind the times. They were cutting edge, a sort of gaming politically correct master-race, that everyone else was expected to evolve into, and you were a loser if you didn’t adapt to the higher consciousness, as per definitions that could only be found with them. They used lots of vague terminology, things like, “Social Contract,” “The Balance of Power,” “Breaking the Game,” etc.

Here’s an example of their dictionary definitions, there’s something like 100 terms, so this is just a tiny slice, but it’s an ugly enough indication of the domination of debate through language they were aiming for. Notice the agenda they feel the need to define for their followers/sheeple:

“Breaking the game

A dysfunctional Technique of Hard Core Gamist play, characterized by rendering other participants’ efforts ineffective without recourse.”

“Competition

Conflicts of interest such that goals achieved by one person bring a disadvantage to one or more others. Competition may operate independently (a) among people engaged in role-playing or (b) among imaginary characters. An example of a Dial during play. Competition may or may not be associated with Gamist play, but when it is present among people, Gamist play is very likely to be occurring. See Gamism: Step On Up.”

(Notice that Gamist play is presumed to be likely the source of the problem, here)…

“Congruence

Play in which two or more different Creative Agendas may be expressed in such a way that they neither interfere with one another nor are easily distinguished through observation. The term was coined by Walt Freitag in GNS and “Congruency”. A controversial topic.”

( An emphasis on highlighting controversial topics. This isn’t just a chance comment they are highlighting here)

“Fantasy Heartbreaker

A published role-playing game which retains specific aesthetic assumptions from pre-3rd edition versions of Dungeons & Dragons. See Fantasy Heartbreakers and More Fantasy Heartbreakers.”

(The emphasis on aesthetic assumptions is laid out more clearly in other articles, and the old games are basically worthless, in a linear scale to the present).

“Force

The Technique of control over characters’ thematically-significant decisions by anyone who is not the character’s player. When Force is applied in a manner which disrupts the Social Contract, the result is Railroading. Originally called “GM-oomph” (Ron Edwards), then “GM-Force” (Mike Holmes).”

(GMs abusing poor players, one of several specialized terms they highlighted a need for. Sure, Railroading exists, but it isn’t oppression. Go play with another group, already!)

“Typhoid Mary

A GM who employs Force in the interests of “a better story,” usually identifiable as addressing Premise; however, in doing so, the GM automatically de-protagonizes Narrativist players and therefore undercuts his or her own priorities of play, as well as being perceived as a railroader by the players. An extremely dysfunctional subset of Narrativist play.”

“Lumpley Principle, the

“System (including but not limited to ‘the rules’) is defined as the means by which the group agrees to imagined events during play.” The author of the principle is Vincent Baker, see Vincent?s standard rant: power, credibility, and assent and Player power abuse.”

“Social Contract

All interactions and relationships among the role-playing group, including emotional connections, logistic arrangements, and expectations. All role-playing is a subset of the Social Contract.”

They were forever talking about GMs not being attentive enough to players’ needs as creating ‘Social Time Bombs.’

These guys needed to take fewer classes on marxist semiotics as applied to personal profiteering. Communist psychobabble, in the service of naked social darwinist capitalism.

Maybe Justin has some thoughts for an article on where he was during the whole era of this stuff going on, and why he still sticks with non-indie games, like 3.5 and Pathfinder?

They generated a lot of intentional conflict, as it generated attention and profits. There is one guy online with a site, the RPGPundit, who now owns his own site, and talks about how these characters keep popping up.