Go to Table of Contents

A guild of brass and bronze workers which actually serves as a focal point for Vladaam chaositech research.

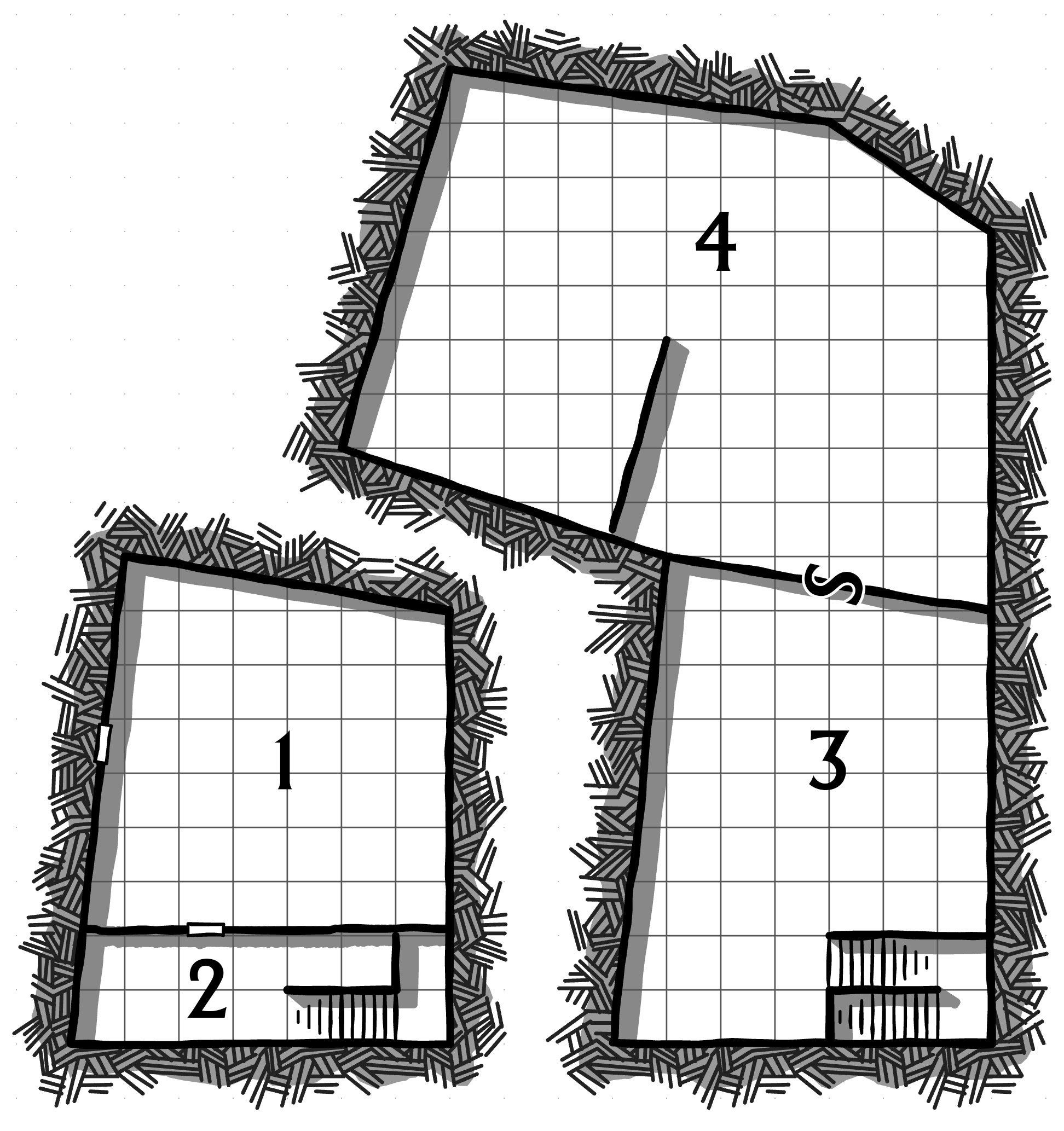

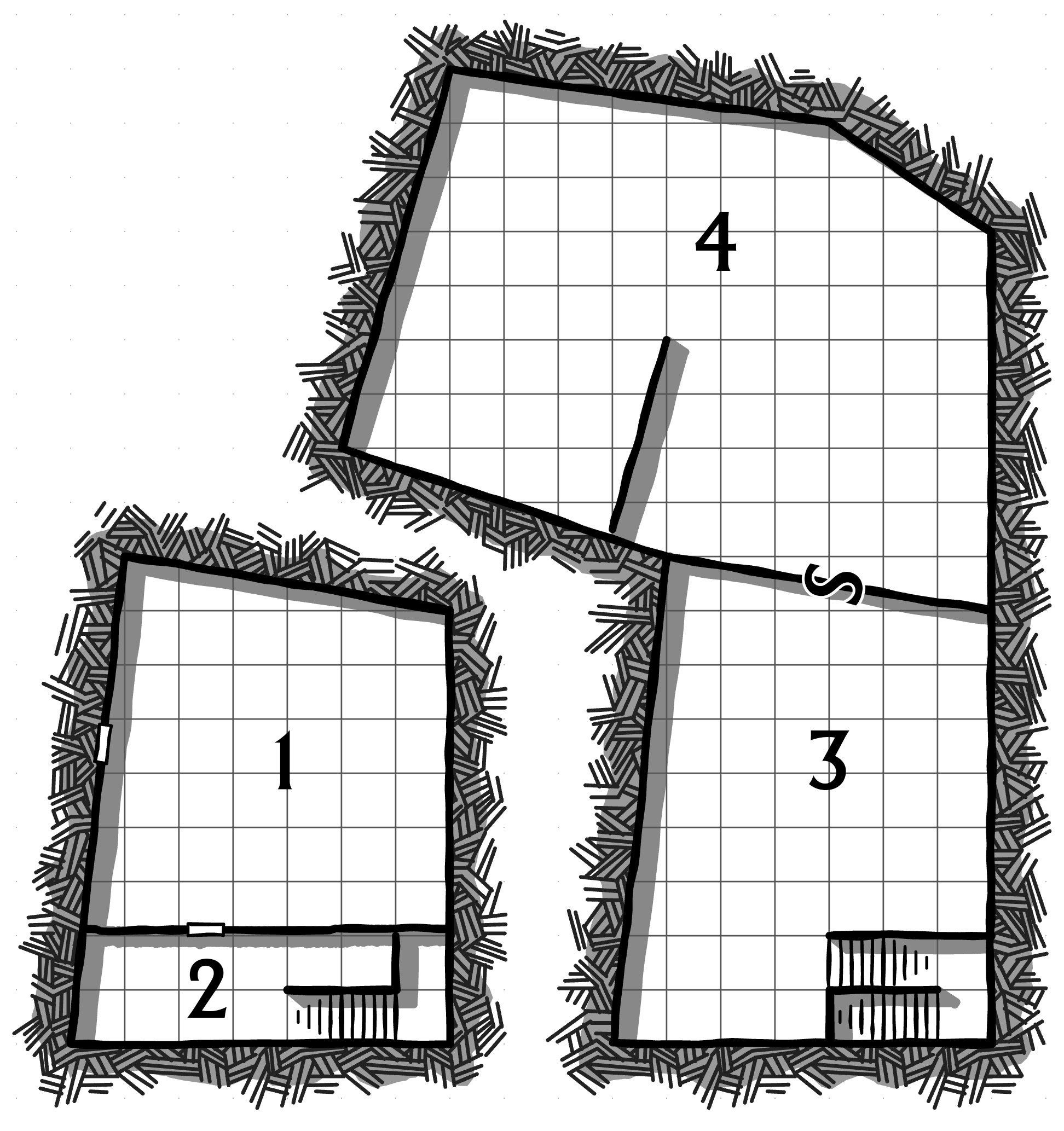

| DENIZENS - DAY | Location |

| 2 Guild Apprentices + Vladaam Guard | Area 1 |

| Vladaam Guard | Area 2 |

| Apprentices + Master Craftsman | Area 3 |

| 3 Chaositech Masters + 2 Apprentices | Area 4 |

| DENIZENS - NIGHT | Location |

| Vladaam Guard | Area 2 |

GM Note: One of the Chaositech Masters is named Astrek, who recently sent hellsbreath rifles to Captain Morsul (see Part 16D: Eye of the East).

Guildsman District

Brass Street – H8

AREA 1 – STOREFRONT

A variety of workbenches cluttered with tools. Guildsmen on duty here will do minor repair work.

TOOLS: Two sets of jeweler’s tools and a set of tinker’s tools.

MERCHANDISE: Various works of brass and bronze, mostly knick-knacks, cheap candelabras, or specialized components of little value. Total worth of 150 gp if it’s all hauled out of here. There are two sextants worth 250 gp each and a set of brass marbles worth 1 gp.

AREA 2 – STAIRWELL

The stairwell is guarded with three alarm spells which are triggered by anyone traversing the stairs who isn’t wearing a guild badge.

- An audible alarm (heard throughout the workshop and out on the street).

- A mental alarm that notifies Aliaster Vladaam.

- A mental alarm that notifies the guioldmaster.

AREA 3 – UPPER WORKSHOP

This workshop contains ten sets of smith’s tools, two sets of tinker’s tool, and two sets of jeweler’s tools., along with a large supply of brass, bronze, and copper (2,000 pounds, worth a total of 1,000 gp). Two small forges are positioned near windows (for ventilation).

PAPERS: A few miscellaneous papers are strewn about, including a Bill for Repairs Done to a Spiked Pit Trap.

SECRET DOOR – DC 16Intelligence (Investigate): The chaositech workshop in Area 4 is actually the second floor storey of the building next door (which has no access to its second floor, just a long stair that goes up to its third floor), so it’s not immediately apparent that there should be any access to it.

BILL FOR REPAIRS TO A SPIKED PIT TRAP

To the attention of Arquad—

A request of remuneration for the services of the Founders’ Guild in the repair and servicing of the safeguards in the back hall of Marquette’s Textiles, Pitch Street, Guildsman District.

To whit—

Repair of hinge mechanisms in door.

Replacement and treatment of spikes.

Additional items—

Blue whinnis commissioned from the Poisoners’ Guild on Black Str. Paid in full. Inc. in billed amount.

Billed amount—

1,875 gold thrones.

GM Background: The trap mentioned here is located in the hallway of Part 17: Undead Shipping Warehouse. The poison (blue whinnis) is being sourced from Part 7B: Alchemy Lab 2 – Poisoner’s Guild.

AREA 4 – CHAOSITECH WORKSHOP

A faint, pink-purple haze clings to the ceiling. There’s sickly-sweet scent raw with some form of potent pheromone. (Ask the players what the emotional reaction of their PCs is to the powerful pheromones.) Strange machinery – some combination of bronze and an unidentifiable black metal – crawls up the walls, although it’s difficult to tell where one device ends and another begins. Several work tables in both halves of the room are covered with softly bubbling chemicals, strangely glowing items, and an eclectic effluvium of technomantic components.

CHAOSITECH: Among a variety of half-completed devices and experiments, there is a sickening rod and blight bomb. There is also a copy of the Book of Greater Chaos. (See Addendum: 5E Chaositech.)

RIFLE CRATE: An open crate that originally contained 12 hellsbreath rifles from the Shuul Foundry. 6 remain in the crate, 2 others have been partially disassembled (and are in various states of study), and 4 have been repacked into a smaller container with a note attached: “Have these sent to the security cache in the temple on Malav Street.”

- GM Note: The temple referenced in the note is Part 6: Abandoned Temple of the Great Mother. The crate was stolen from the Shuul.

IRON COFFER (10% chance): There’s a 10% chance of an iron coffer containing 500 gp, 40,000 sp, and 50,000 cp with instructions to have the Ithildin couriers ship it to the Red Company of Goldsmiths on Gold Street (see Part 12).

STAT SHEET

Guild Apprentices: Use artisan stats, Ptolus, p. 606.

- Proficiency (+2): Arcana, Smith’s Tools

- Equipment: dagger, hourglass, magnifying glass, oil of mending (x2), Vladaam deot ring

Master Craftsman: Use artisan stats, Ptolus, p. 606.

- Proficiency (+2): Smith’s Tools

- Equipment: hourglass, magnifying glass, oil of mending, Vladaam deot ring.

Chaositech Master: Use mage stats, MM p. 347.

- Proficiency (+3): Medicine, Chaositech Tools, Smith’s Tools

- Equipment: oil of mending, chaositech tools, chaos storage cube (Ptolus, p. 535), any 1 chaositech weapon (Ptolus, 535), Vladaam deot ring

- Chaositech Stabilizaiton: 50% chance of negating chaotic failure of chaositech device.

- Resist Insanity: Advantage on saving throws made when working with chaositech.

- Tinker: Work 1d4+6 days to double a chaositech item’s range, area, duration, or add +2 to its damage or save DC.

Spellcasting: 9th-level spellcaster. Spell save DC 14, +6 to hit with spell attacks.

- Cantrips (at will): acid splash, dancing lights, mage hand, sense spell (Ptolus, p. 632)

- 1st level (4 slots): detect chaositech (Ptolus, p. 628), mage armor, magic missile, shield

- 2nd level (3 slots): meld into stone, siphon (Ptolus, p. 633)

- 3rd level (3 slots): counterspell, gaseous form, lightning bolt

- 4th level (3 slots): private sanctum, stoneskin

- 5th level (1 slot): mislead

Vladaam Guards: Use guard stats, MM p. 347, with AC 17. (Equipment: breastplate, shield, longsword, longbow, arrows x20, potion of healing, Vladaam deot ring.)

Go to Part 12: Guild – Goldsmiths